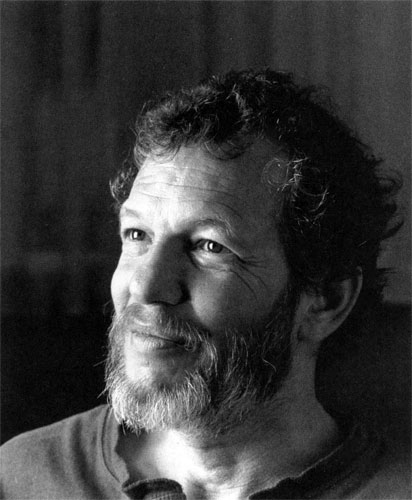

Stephen Levine has been working with the terminally ill and the grieving for nearly two decades. His books include A Gradual Awakening, Who Dies?, Healing into Life and Death, and, most recently, Guided Meditations, Explorations and Healings (all published by Doubleday, Anchor Books). He and his wife, Ondrea, lead workshops and meditations for the dying and their families, and are also the co-directors of the Hanuman Foundation Dying Project. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Managing Editor Carole Tonkinson.

Tricycle: Buddhist teachers say that if one commits suicide, it will create negative circumstances for one’s next life. How do you reconcile this with euthanasia?

Levine: From talking to various lamas and meditation masters through the years, I have come to understand that the negative karma that terrifies so many people is the karma for the way in which most people commit suicide—the sloppiness, the impatience, the lack of concern for those left behind. The people Ondrea and I have seen—either through suicide or through an assisted death—leave their loved ones with gratitude and a powerful reinforcement of their love. The act in itself is neither wholesome nor unwholesome.

Tricycle: From a Western perspective, the question of pain is primary, but the Buddhist perspective asks us to consider consciousness. How does this difference in emphasis come into play when addressing the many ethical questions raised by euthanasia?

Levine: A distinction between pain and suffering may well be the distinction—in a highly oversimplified way—between the worldviews. In a Buddhist view mental and physical pain are a given but suffering is not a given—it is a reaction to pain. If we stub our toes, Westerners are conditioned to send hatred into the pain, to ostracize that part of the body which most calls out for our embrace. We are conditioned to suffer, to turn pain into suffering, by tightening the mouth, by shutting down, scrambling for safe territory. But there is no safe territory. A Buddhist can use pain as a means to end suffering and use discomfort as a means of awakening the mind—the goal is not withdrawal from pain.

Tricycle: Much of your work concerns the possibility of an inner transformation when accepting death. Are you talking about enlightenment?

Levine: I’m talking about when the heart of the dying person is open and the mind is, on many levels, clear. We must be very careful of the process—there isn’t a goal in dying. The point is simply to be with the process, and as people are with it, their heart and deeper levels of being, rise to the occasion. But all models create suffering, even a model of conscious dying, which is intended to relieve it.

Tricycle: Does one need to be sure consciousness cannot be revived before taking an action that would end a life?

Levine: That would depend on your agreement with that person. When it comes to the question of euthanasia, for there to be a clear and conscious connection between a patient and facilitator, nothing can be left unsaid. The person dying needs to state wholly and repeatedly a desire to leave the body behind, and the facilitator must sense the appropriateness or inappropriateness of their own participation in such an activity. I have been with people who chose to leave their body while conscious rather than live through their next period of suffering and humiliation and the loss of choice.

Tricycle: What would you say to a proxy who feels a conflict because a patient he is caring for may be experiencing a transformation of consciousness, but, at the same time, the life support is costing hundreds of thousands of dollars?

Levine: This question bothers me. Why should someone experiencing a transformation of consciousness be of any more value than someone who’s not? The very asking of this question creates a sense of hierarchy as to who is worth supporting and who isn’t. A person’s clarity, consciousness, and purity should and must have nothing to do with the recognition of the preciousness of that person’s process. Of course that means an honoring of their decisions about that process. Not to second-guess what is best for them, but, as always, to use this as work on ourselves, to confront ourselves if we are feeling pity rather than love and compassion. If financial considerations are a factor in the decision to suspend life support, that is just another sign of the degeneration of a brokenhearted America.

Tricycle: What other kinds of considerations does a Buddhist facilitator have to be aware of in fulfilling his or her obligation—whether the person they’re caring for is a Buddhist or a non-Buddhist?

Levine: Well, there are a couple of different kinds of euthanasia: one, where you have a contract with a person, and they have chosen to leave under a certain set of circumstances that are very clearly communicated on numerous instances; the other is the question of when to relieve suffering without communicating with the patient. In my experience with those who have chosen euthanasia, all considerations have been very clearly elucidated, well before the period of physical or mental incompetence set in.

Tricycle: But if a person is not able to communicate—and has not left any prior instructions—what would a facilitator look for as a sign to pull the plug?

Levine: We live in a time perhaps unparalleled in history. We can keep people alive against their will and we may not even know it is against their will. We can force people to stay alive in the most abject suffering. Caretakers must be very watchful under these circumstances. Don’t make people die for you. When it’s your turn, see what decisions you make. In the meantime, be very mindful of fear rather than love. Be very mindful of intent. It takes pure heart, enormous “don’t know mind,” to follow this path of compassion—aiding someone’s death—in the face of so many religions warning against doing so.

Tricycle: What is your view of the Hemlock Society and the work of Dr. Kevorkian?

Levine: They seem well-intended. I think they are good examples to us all of how “clean” we need to be in this work. Any taint of self-interest is very much to be examined and avoided.

Tricycle: Are there cases you have experienced when it was clearly appropriate to end a life?

Levine: Yes. Ondrea and I have been involved with seriously ill people who were left unable to care for themselves, and unwilling to continue in those unimaginably difficult circumstances. In certain cases some who had chosen to end their lives were aided in their release from untenable situations. Before we judge another’s dying, I ask you, “Would you sell your death, if someone came to you and gave you five million dollars to buy your death, and promised that you will live to be five hundred years old, no matter what?” Who would be foolish enough to sell their death? Who would chance five hundred years in an iron lung? We count on our death. We never would have taken birth if we weren’t absolutely sure, certain, that death would allow a release if the agony, the suffering, became too great. Death makes life safe.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.