William Burroughs was not a Buddhist: he never sought or found a “teacher,” he never took refuge, and he never undertook any bodhisattva vows. He did not consider himself a Buddhist, nor, for that matter, did he ever declare himself a follower of any one faith or practice. But he did have an awareness of the essentials of Buddhism, and in his own way, he was affected by the Buddha-dharma.

From his earliest childhood in St. Louis, Missouri, in the 1920s, Burroughs was alienated and repulsed by the personal and social hypocrisy that he could not help but perceive around him, even at the age of eight or ten. He was terribly shy, and frightened of the other children, but at the same time defiant in his own beliefs and inclinations—including his homosexual attraction to some of his classmates. A sense of being fundamentally “different” from the others marked his childhood, and never left him.

Jean-Paul Sartre said, “Hell is other people”; the young William Burroughs said, “Other people are different from me and I don’t like them.” His response was to develop an obsession with weapons and self-defense, which lasted all his life. William sometimes affected a self-image exemplified by the lyrics of a blues song of the 1920s, which he often quoted in later years: “I’m evil, evil as a man can be / I’m evil, evil-hearted me.” But his heart wasn’t really in it, all this evilness; there was within him some bedrock of decency that always stopped him from elaborating himself fully in that direction.

In his twenties Burroughs saw a series of psychoanalysts in the hope that it might allow him to break free of the psychic constraints and self-defeating reflexes that he felt as a lifelong curse. Then when he was thirty, in New York, Burroughs met Kerouac and Ginsberg, and after a period of several months during which he was conducting his own “lay analyses” of his new friends, his recently developed addiction to morphine began to take the place of his analytic efforts. He had abandoned all faith in psychiatry by the age of forty-five, but long before that he had concluded that the Freudian model of “cure of neurosis through recuperation of primordial trauma” was overrated.

By 1949, Burroughs was living in Mexico City with Joan Vollmer, a bright young woman with whom he felt a deep kinship despite his essential homosexuality. Joan was killed accidentally in 1951 when William fired a shot from a pistol at a glass she had placed on her head. Within three years he was living a life of squalid excess in Tangier, still struggling to understand how this had happened.

Burroughs felt he was defending his Self not only from outer opponents, but also from an inner enemy: the Ugly Spirit, as he called it. He felt that he was literally “possessed” by an inimical, invading personality with its own will that was quite contrary to his best interests. And in his efforts to understand his shooting of Joan, he could proceed no further than to see an eruption of the Ugly Spirit in that rash, drunken act.

His letters from Tangier to Kerouac and Ginsberg were a lifeline for Burroughs. In the series of letters he wrote to his friends from 1953 to 1955 we find references to yoga and Buddhism, probably in response to the enthusiasm Ginsberg and Kerouac relayed in their own letters to him (now lost) for the Eastern traditions they had recently discovered. (Ginsberg had been inspired to look into Zen Buddhism after seeing some Chinese paintings in the New York Public Library in April 1953, and Kerouac had found Dwight Goddard’s A Buddhist Bible in the San Jose, California, library in 1954.)

To Kerouac, May 24, 1954, from Lima, Peru:

As you know I picked up on Yoga many years ago. Tibetan Buddhism, and Zen you should look into. Also Tao. Skip Confucius. He is sententious old bore. Most of his sayings are about on the “Confucius say” level. My present orientation is diametrically opposed [to], therefore perhaps progression from, Buddhism. I say we are here in human form to learn by the human hieroglyphics of love and suffering. There is no intensity of love or feeling that does not involve the risk of crippling hurt. It is a duty to take this risk, to love and feel without defense or reserve. I speak only for myself. Your needs may be different. However, I am dubious of the wisdom of side-stepping sex.

To Ginsberg, July 15, 1954, from Tangier:

Tibetan Buddhism is extremely interesting. Dig it if you have not done so. I had some mystic experiences and convictions when I was practicing Yoga. That was 15 years ago. Before I knew you.

To Kerouac, August 18, 1954, from Tangier:

My conclusion was that Buddhism is only for the West to study as history, that is a subject for understanding, and Yoga can profitably be practiced to that end. But it is not, for the West, An Answer, not A Solution. We must learn by acting, experiencing, and living; that is, above all, by Love and Suffering. A man who uses Buddhism or any other instrument to remove love from his being in order to avoid suffering, has committed, in my mind, a sacrilege comparable to castration. You were given the power to love in order to use it, no matter what pain it may cause you. Buddhism frequently amounts to a form of psychic junk…

I can not ally myself with such a purely negative goal as avoidance of suffering. Suffering is a chance you have to take by the fact of being alive.

I repeat, Buddhism is not for the West. We must evolve our own solutions.

“Suffering is a chance you have to take by the fact of being alive.”—Here we see a glimpse of the First Noble Truth, but from a distinctly Romantic/Heroic standpoint. For Burroughs, it is our duty to suffer, and to learn from suffering. But he was referring primarily to sexual or romantic love, in which he had suffered much.

As for the notion of Buddhism as “psychic junk,” here is an irresistibly funny bit from Naked Lunch, the novel he was writing in Tangier:

[“a vicious, fruity old Saint applying pancake from an alabaster bowl”]:

“Buddha? A notorious metabolic junky . . . Makes his own you dig. In India, where they got no sense of time, The Man is often a month late . . . Now let me see, is that the second or the third monsoon? I got like a meet in Ketchupore about more or less.’

“And all them junkies sitting around in the lotus position spitting on the ground and waiting on the The Man.

“So Buddha says:I don’t hafta take this sound. I’ll by God metabolize my own junk.’

“Man, you can’t do that. The Revenooers will swarm all over you.’

“Over me they won’t swarm. I gotta gimmick, see? I’m a fuckin’ Holy Man as of right now.’

“Jeez, boss, what an angle.’”

These writings indicate that Burroughs misunderstood Buddhism. A motivation to “avoid suffering” is merely another form of craving, after all. And in Mahayana Buddhism the bodhisattva vows not to seek nirvana, but to be reborn for as long as other sentient beings remain unliberated by enlightenment.

In Tangier in the mid-1950s Burroughs had sunk into an abject stasis of severe addiction. As he wrote in a 1962 foreword to Naked Lunch:

I lived in one room in the Native Quarter of Tangier. I had not taken a bath in a year nor changed my clothes or removed them except to stick a needle every hour in the fibrous grey wooden flesh of terminal addiction. I never cleaned or dusted the room. Empty ampule boxes and garbage piled to the ceiling. Light and water long since turned off for non-payment. I did absolutely nothing. I could look at the end of my shoe for eight hours.

While it is certainly misguided to confuse an opiate stupor with a transcendental state, it is undeniable that narcosis facilitates detachment, and Burroughs saw a rough equivalence between the cellular apathy of the stoned junky and the transcendental stillness of the meditator. And in a way, he was sort of on target: “emptying the mind,” which is a preliminary stage in sitting practice, was the goal he was eternally seeking. But the subjective effect of junk is more like “emptying the heart,” that is, numbing painful emotions such as unrequited love, self-loathing, and remorse. So again there is a misunderstanding, and a serious contradiction. Burroughs claimed to reject the “purely negative goal” of avoidance of suffering—but what else was he doing by using narcotics?

In the late 60s, Burroughs was impressed by Vipassana practice. From these impressions of Vipassana, Burroughs evolved a mindfulness methodology of his own, tailored to his solitary life in London during those years: the “Discipline of D.E.,” or “Do Easy.” This was an elaborate system for carrying out household chores with a minimum of physical effort. For example:

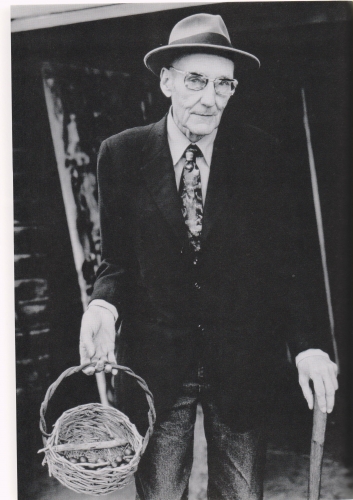

Colonel Sutton-Smith, 65, retired not uncomfortably on a supplementary private income flat in Bury Street St James cottage in Wales

The Colonel Issues Beginners DE

“DE is a way of doing. It is a way of doing everything you do. DE simply means doing whatever you do in the easiest most relaxed way you can manage which is also the quickest and most efficient way as you will find as you advance in DE.

“Never let a poorly executed sequence pass. If you throw a match at a wastebasket and miss get right up and put that match in the wastebasket. If you have time repeat the cast that failed. There is always a reason for missing an easy toss. Repeat toss and you will find it.”

Here is what I consider Burroughs’ urbane equivalent of “chop wood, carry water.” It also reflects the tedious solitude of his life toward the end of his London years (1960-1973), and his queer bachelorhood after a seven-year love affair ended in 1966. By this point he was middle-aged, committed to his career as a writer, and mostly out of danger from the youthful obsessions of romantic love.

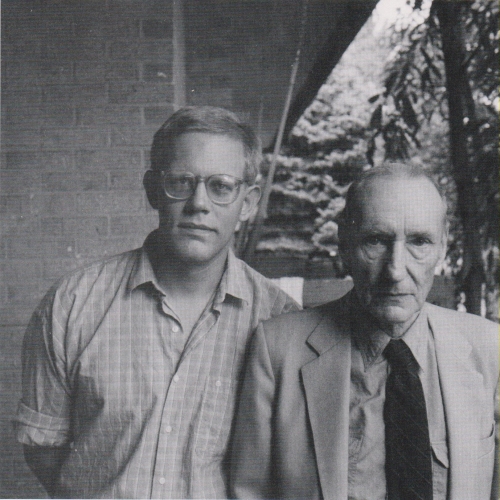

In 1975, at age sixty-one, William was asked by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman to come to Naropa [The University in Colorado founded by Trungpa Rinpoche] and give some classes and readings. William had encountered Trungpa in London in the 1960s, but it was in the summer of 1975 that he became personally acquainted with him. Burroughs had already met a number of advanced spiritual leaders of one kind or another, and I think he already saw himself as one of them, a “holy man” of sorts. So William’s stance toward Trungpa was collegial, with the mutual professional respect accorded by one showman to another—a kind of show-biz camaraderie. And I saw that Trungpa seemed to regard William in a similar light.

Now, you should know that a lot of controversy was caused by some of Trungpa’s behavior, and a lot of American poets and writers were offended by Ginsberg’s embrace of Trungpa as his teacher and his establishment of the Kerouac School under the aegis of Naropa Institute and the Nalanda Foundation, in Boulder. The fact that Trungpa smoked cigarettes and drank a lot of alcohol, that he created a force of personal bodyguards called “Vajra Guards” and outfitted them in special quasi-military uniforms, etc., didn’t sit well with some people’s idea of how a spiritual teacher should behave—at least in America. There were some incidents of confrontation and misunderstandings.

But none of these things perturbed William in the slightest. He understood that holy men are eccentric by definition, and that showmanship and personal flair are standard tools in the shaman’s medicine bag. Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom” appealed to Burroughs. Trungpa invited William to spend a few weeks in solitary retreat at his facility in Barnet, Vermont, called Tail of the Tiger (now Karme Choling). Trungpa told William he should leave his typewriter at home and do no writing while he was living alone in the little cabin, but Burroughs brought along a notepad, and his notes from that period were published in 1976 as The Retreat Diaries. Here is what he wrote in his introduction:

…I am more concerned with writing than I am with any sort of enlightenment, which is often an ever-retreating mirage like the fully analyzed or fully liberated person. I use meditation to get material for writing. I am not concerned with some abstract nirvana. It is exactly the visions and fireworks that are useful for me, exactly what all the masters tell us we should pay as little attention to as possible. I sense an underlying dogma here to which I am not willing to submit. The purposes of a Bodhisattva and an artist are different and perhaps not reconcilable. Show me a good Buddhist novelist.

So as far as any system goes, I prefer the open-ended, dangerous and unpredictable universe of Don Juan [Enigmatic writer Carlos Castaneda chronicled his apprenticeship to Yaqui Indian sorcerer Don Juan Matus in The Teachings of Don Juan and many other books Ed.] to the closed, predictable karma universe of the Buddhists.

Indeed existence is the cause of suffering, and suffering may be good copy. Don Juan says he is an impeccable warrior and not a master; anyone who is looking for a master should look elsewhere. I am not looking for a master; I am looking for the books.

As I have said, William was quite at home in the solitary state, and he spent countless hours alone, meditating in his own way, as a matter of course. Perhaps his two weeks in the Vermont cabin were more a change of scene than anything else.

William lived in Boulder from June 1976 through October 1978, although he was only scheduled to spend a week or two at the outset. He stayed on because his twenty-nine-year-old son, Billy, came to town for Naropa in the summer of 1976 and was immediately hospitalized with acute liver failure. William was very close to everything happening to Billy, and he was with him through many horrific experiences. Billy’s physical, psychological, and spiritual collapse came down hard and right in William’s sixty-two-year-old face.

Billy Burroughs died at age thirty-three in March 1981. His son’s death and his move to the Midwest prepared the ground for William Burroughs’ bodhi, the awakening of his tender heart to the limitless field of compassion, and the vector of this awakening in his life arrived in the form of cats. By the time The Western Lands was published in 1987, William had become a dedicated cat-lover, with a household full of the animals. His cat-inspired meditations can be found in the last part of The Western Lands and, of course, inThe Cat Inside, where he wrote:

My relationship with my cats has saved me from a deadly, pervasive ignorance. […]

This cat book is an allegory, in which the writer’s past life is presented to him in a cat charade. Not that the cats are puppets. Far from it. They are living, breathing creatures, and when any other being is contacted, it is sad: because you see the limitations, the pain and fear and the final death. That is what contact means. That is what I see when I touch a cat and find that tears are flowing down my face.

In the mid-1980s William went through a period of deep sadness and depression, reviewing a life’s catalog of mistakes and regrets. This seems to have resulted in a kind of spiritual awakening, because by the end of his life ten years later he really had become enormously sweet and tenderhearted. I don’t mean saccharine-sweet—William was salty and irreverent and funny to the end—but he was more patient, more kindly, more considerate, more grateful, and more gracious. I would say he was trying to extinguish the Second Fire, ill will, and to stave off the onset of the Third, mental dullness or boredom.

As death approached, William was writing in what he knew would be his final journals. In these he wrestled with his anger at man’s bottomless ignorance. I think he never stopped believing that, in the words of Sri Aurobindo, which he often quoted: “This is a War Universe”—and he always saw himself in the warrior’s role. But by some dispensation of his own curious karma, including all the social and historical baggage he was born with, and all the passions he felt and violent actions he took in his life, William Burroughs was given a final decade of old age in which to look back upon that life and study its lessons—and, with the help of his beloved cats, he attained a state of compassion for the suffering that is everywhere.

I’d like to close with these lines from The Place of Dead Roads:

“Whenever you use this bow I will be there,” the Zen archery master tells his students. And he means there quite literally. He lives in his students and thus achieves a measure of immortality. And the immortality of a writer is to be taken literally. Whenever anyone reads his words the writer is there. He lives in his readers.

This article is an abridged version of a lecture given at Naropa Institute on June 24, 1999.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.