Antony Gormley is an acclaimed British artist whose sculpture has revolutionized the expression of the human body in art. He has gained particular recognition for making casts of his own body and manipulating them to challenge viewers’ perceptions of space, identity, and time. A former student of the renowned Vipassana teacher S. N. Goenka’s, Gormley found that his experience with meditation heightened his awareness of the body and influenced its expression in his work. Tricycle Associate Editor Caitlin Van Dusen interviewed Antony Gormley by phone in May 2002. Just prior to the conversation, Gormley had emerged from a body casting, in which a plaster cast is made of his body and then used as a form for his sculptures.

So you’ve just finished a body casting?

So you’ve just finished a body casting?

Yes, that’s right. Just out of the shower and out of the cast.

What is the process that you go through in making a body cast?

The process is very simple, really. I do it with my assistants here in my studio. I use cling film—I think you call it Glad Wrap—as a separator between body and plaster. And then I get into the state of mind and the position that I want.

I’m curious what the experience is like for you.

Well, it’s a mixture of coming out of a sauna, coming out of a meditation session, and coming out of a very refreshing kind of deep sleep. There’s always a bit of pain involved, too. You use your will to put yourself in a position where you abandon it. It’s a curious kind of cusp.

Do you use body casting as a form of meditation?

Yes. I don’t sit formally anymore, which is to say that I sit occasionally, but I don’t do it in the way that I did properly for about six years, when I was practicing vipassana twice a day. My practice is my sculpture now.

Would you speak briefly about your experience with vipassana meditation?

On arriving in India in 1972, I just happened to meet some Tibetans who took me to Dalhousie, where S. N. Goenka was teaching a ten-day vipassana course. I joined up and stayed for not one course but two, and then I went on to do eight more courses with Goenka over the next two years.

Did you find that your art changed in any significant way as a result?

It didn’t happen immediately, but I still think that coming in touch with Goenka and learning vipassana meditation was the single most important experience of my life. Still, I wouldn’t characterize my work necessarily as “Buddhist” sculpture, but I think that there are aspects of mindfulness that are intrinsic to the work and that make it a potential instrument for mindfulness. For instance, most of my work over the last three years has involved the simplest standing positions. For many years I avoided these positions because I thought they conveyed a rather common idea about what a sculpture was: a sculpture was a statue, and a statue stood somewhere. But the thing about statues is that they take standing for granted. I became more and more fascinated by the idea that you shouldn’t take standing for granted, and I came to see how standing is an extraordinary state. I got interested in just trying to stand, being fully conscious of the relationship between the limbs.

How would you relate your work to the Buddhist ideas of impermanence and self-awareness?

I accept absolutely the tenet that nothing has a changeless identity. Sculpture is, in a sense, an attempt to slow things down, to concentrate stillness in an object. Through this stillness, the movement of life becomes felt and can itself be stilled—or have a point of reference for stillness, anyway. But for my work, it’s also important to consider: Whose body is this? Well, it is somebody. It is evidence of a particular moment, of a particular body in a particular position or place.

Is that why you choose to make your own body the focus, rather than inventing a body?

Yeah. I believe that sculpture ought to come from a lived moment rather than from an idea or an image. I think of all of my works as identifying a very particular human space in a very general space-at-large. The idea for me is that it’s sculpture that is worked on from the other side of appearance, from a position of radical subjectivity, which in the end, I’ve learned through meditation, is a common human condition.

I’ve read that you are interested in the Theravada Buddhist practice of metta [lovingkindness] meditation, in which, in your words, one “transmits love as a vibration that is registered in that space of the darkness of the body.” It seems from what you’ve just said that perhaps the empathy between the viewer and the sculpture might be an enactment of this transmission.

I think that the extraordinary thing about the cultivation of metta, as opposed to Christian ideas of love, is that it is a transpersonal force. When you concentrate on transmitting metta, it’s like you’re not actuallydoing it, you’re just opening yourself up to this field of potential sympathy that exists between all sentient beings. It interests me more and more how the viewer can become the viewed. I like very much the idea of reciprocity.

You use different materials—lead, clay, steel—for the sculpture’s “skin,” its boundary between the viewer and the viewed. How do you decide what degree of reciprocity each medium implies and what you want to convey with it?

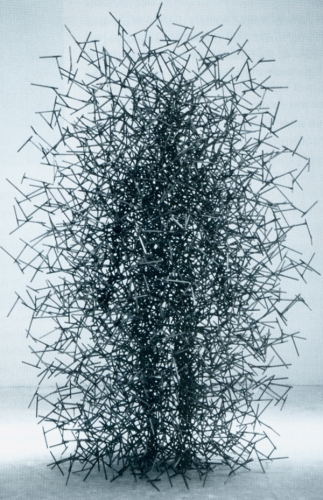

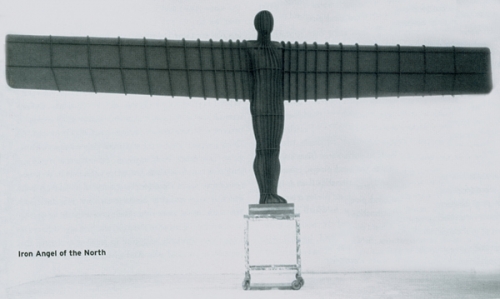

I think all materials come with their own vibrations, their own qualities, and their own particular potency, and you try to use them in a way that is fitting to their nature. The most recent iron works I’ve been making are simple body forms that display their ironness by having a very smooth surface that is exposed to the elements. It rusts, but initially in very clearly defined rain patterns that declare the fact that this is an earth material, that this is changing, that this is organic, that this has a relationship with air and with water. That’s almost in opposition to the Quantum Cloud pieces, created in stainless steel, whose primary relationship is with light, as opposed to air. The Quantum Cloud pieces relate precisely to the experience of vipassana, in which the edges of the body are completely lost, and the body is indicated not as an object with a determined, liminal skin that separates space from the object, but as energy.

The art historian John Hutchinson once remarked that to him, some of your pieces suggest in-breaths and others out-breaths.

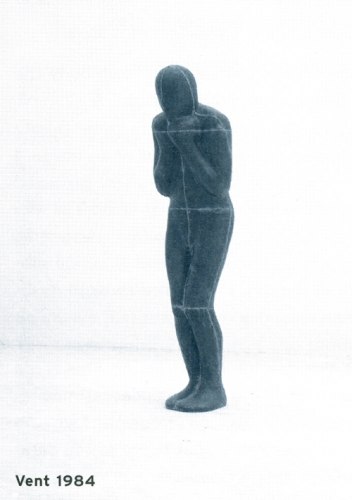

I think it’s a very nice way of thinking about the relationship between inhibition or repression and the idea of what happens when you open yourself and you become a zone that things can pass through. The Quantum Cloud pieces are very much about exhaling, allowing things to dissolve into the space around them, whereas an early work like “Vent” is holding things in.

A piece like “Case for an Angel” seems to me to be both: you have the central figure that is contained while stretching its arms outward.

That piece is trying to deal with place and extension at the same time, and it’s an impossible paradox: the idea that we are, in anyone moment, always in one place, always contained within our own embodied selves, while at the same time we have this potential for imaginative extension.

What do you hope your work elicits in the viewer?

What I hope the work does is use embodiment—the representation of embodiment—to cause the viewer to become reflective of his or her own position in space. This “body in space” that is the sculpture then engages with the viewer as another “body in space.” I think one of the things sculpture can do is make you more conscious of your own position in space through the agency of its foreign body, which is inert and may be there on very different terms. You walk into a room or a clearing in a forest, or you see an object by the sea or in the road, and you say, What’s this doing here? And the sculpture in some way returns that question to you and asks, And what are you doing? ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.