In the summer of 1974, when poet Jane Hirshfield drove down the steep and dusty road to the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center just inland from the rugged northern California coast, no one was expecting her. “But I unwittingly sat my first tangaryo,” says Hirshfield, alluding to the Zen tradition of a student demonstrating her commitment by sitting steadfastly at the entrance to the monastery, for days if necessary. “I just refused to leave.” Twenty-one years old, pitching herself from East Coast to West Coast, Hirshfield couldn’t have imagined where this journey would ultimately lead her, what future success she would have as a poet, or how deeply Zen and poetry would intertwine in her life. She stayed only a week that first time at Tassajara—the first Zen training monastery in the West, founded by the late Shunryu Suzuki Roshi—but would soon return for three years in residence.

Hirshfield had been writing since she was a child and won The Nation prize for undergraduate writing, but during her residence at Tassajara she did not write at all, focusing instead on her Zen studies. Since leaving Tassajara she has published six collections of poems and a book of essays on “the mind of poetry.” In 2004, she was awarded the Academy of American Poets Fellowship, which puts her in the company of legends like Robert Frost and Robinson Jeffers. Her most recent collection, After, will be published in February by HarperCollins. Although she no longer has a formal Buddhist teacher, she continues to practice Zen sitting meditation, or zazen. “Life is a good teacher, I find, if you pay attention,” she says.

Hirshfield was born in New York City in 1953 to Robert Hirshfield, who worked in the garment industry making housecoats, and Harriet Miller Hirshfield. “No one in my family was literary,” she says, acknowledging that there’s no definitive answer to the question of why she became a poet. It’s easier to trace her spiritual inheritance. Though Hirshfield had minimal exposure to the traditions of her Jewish heritage during her childhood, her maternal great-great-grandfather was a rabbi, and her maternal grandfather, who she describes as “something of a mystic,” was a member of the secretive Rosicrucian Order.

Currently, Hirshfield lives in the Bay Area with Carl Pabo, a molecular biophysicist she affectionately refers to as her “sweetie.” She wears her long, wavy brown hair pinned loosely away from her face, a veil drawn back to frame wide, green eyes. She moves like one who’s practiced at sitting still—with a sense of gatheredness, of curiosity and a capacity for absorption. Her face is deeply expressive, shifting readily between grief, sympathy, and joy—whatever the moment brings.

In the poetry world, Hirshfield is not identified as a distinctly Buddhist poet, partly because there are few direct references in her work to Zen: a reader is just as likely, perhaps even more likely, to find a Greek god or goddess as a monk or Buddha. But it’s also due to Hirshfield’s own desire for her work not to be limiting, or limited, in its relevance. “Teahouse practice—one of four traditional modes of practice in Japanese Buddhism—is a kind of hidden practice,” says Hirshfield. “It describes the old lady who runs the roadside teahouse that everyone likes to go to, but no one can quite say why. That kind of hidden practice is what I’ve always felt appropriate for my poems. It feels truest to my own relationship to practice as something essential in my life—intense, central, pervasive—yet also nothing special.”

In Nine Gates, her book of essays on poetry, Hirshfield writes that a good poem “helps you to wake up,” and that things “speak to us on their own terms and with their own wisdom, but only when approached with our full and unselfish attention.” She could just as easily be speaking of zazen. “Poems,” she says, “are maps to the place where you already are.” Zazen, she says, cultivates the ability to “stay open to what comes and with what comes,” just as a poet’s attention must do in receiving a poem from the imagination.

And yet zazen is not poetry, and poetry is not zazen. Poems are made of words and come to life on a page or when spoken, while zazen is composed of stillness and silence. “When I sit zazen, I don’t write poems,” says Hirshfield, “I am entering a condition of concentration, of being with this moment as it is. And things come up in that which are, of course, inexpressible. . . .But in poetry, it’s almost as if it is the same request made of my deep self, but with the intention pointed toward words rather than toward wordlessness.” Hirshfield was drawn to poetry as a young girl, she says, “because I needed to find a way towards my own self under circumstances where that was not particularly encouraged.” These “circumstances,” in part, refer to the atmosphere of emotional constriction that prevailed in so many American families in the 1950s. Hirshfield saw poetry as a “life raft”—a way to access deep feeling: “I knew that I would never write any poems worth reading if I did not pursue a path of deepening my experience and my ability to discover, express, and simply sit with my own experience.”

As Buddhism teaches, much of the time we filter our experience, sort it into likes and dislikes, things we want to repeat and things we want to avoid. But for both the poet and the Zen practitioner, the task is not to discriminate and deny—to accept only the perfect, unblemished fruit—but simply to see what is for precisely what it is. If we try to smother our emotional demons, says Hirshfield, “it’s like the Greek hydra—cut off one head, nine others spring up in its place.” Rather, what the practice teaches us is to say yes to everything at the deepest level, including the difficult, whether it’s loss, boredom, anger, confusion. Hirshfield captures this idea memorably in a short poem that recalls her time at Tassajara, called “A Cedary Fragrance”:

Even now,

decades after,

I wash my face with cold water—not for discipline,

nor memory,

nor the icy, awakening slap,but to practice

choosing

to make the unwanted wanted.(from Given Sugar, Given Salt, HarperCollins, 2001)

In a Jane Hirshfield poem, we are fully immersed in the fruitful, fragrant realm of the natural world. The objects and images of everyday life—fog, wood, stone, roses, horses—appear and reappear, resonant yet individual, more than mere objects in a landscape. This orientation reflects Hirshfield’s early training in both Japanese and Chinese poetry, where human and nonhuman realms “interpenetrate,” and Zen, which teaches the interconnectivity underlying all things. “Poetic imagination knits nonhuman and human existence into one another,” says Hirshfield. “Even in a poem in which an image seems to be standing in for the self—a mountain landscape, say, signaling solitary withdrawal, or the moon as a figure for the fullness of things or for enlightened mind—we can’t help but also feel through our own experiences the mountains’ life of mountain-ness, the moon’s condition of moon-ness.”

Dogen said that enlightenment is “intimacy with all things,” a quote that Hirshfield refers to often. “I think art brings us to that feeling as well,” she says by way of explanation. “It isn’t possible to make art without a realization of both interconnection and intimacy. . . .If you open yourself to intimacy in any circumstance or situation, your fear will fall away.” And cultivating fearlessness has been essential to her work as a poet. “To find a path to deep thought requires courage. I need to be in a place where I can be absolutely vulnerable and exposed.” This requires sitting with the questions, without expecting certainty or answers. “In Zen,” says Hirshfield, “you don’t get to rest in the absolute or relative world, or in any fixed understanding.”

In her latest book, After, Hirshfield has written a series of poems that embody this principle by regarding their subjects from every possible direction and refusing to settle on any one view. She titles the poems “assays,” a word from the fields of chemistry and mining that refers to analysis of a substance to determine its components. The poems’ subjects range from tangibles like tears to abstract concepts like hope and judgment to parts of speech like the prepositions “of” and “to,” and in these poems, Hirshfield’s playful side comes boldly forth.

“To Opinion”

Though I cannot know for certain,

I doubt the singing dolphins have opinions.This thought, of course, is you.

A mosquito’s estimation of her meal, however subtle, is not an opinion. That’s my opinion too.

That Hirshfield would ruminate on the subject of opinion is not surprising, for the act of making her work public puts the poet directly in the sometimes thorny path of appraisal. Though Hirshfield thinks of herself as someone who would still be scratching poems into the sand even if she were stranded on a desert island without an audience, being a writer is necessarily both a private and a public undertaking.

She muses that for her, publication has “an odd neutrality to it. . . . It just feels like what you do. You wash the dishes, you rake a garden, you send the poems out.” But she also acknowledges the sustaining effect of the fellowship of writers and readers. Just as the sangha nurtures its members in the Zen community, the “sangha of poetry” can offer much needed support and reassurance in walking what can be a difficult and lonely path.

Speaking of her time living in a monastic community, Hirshfield recalls “the intimacy of practicing with others, in a place where every person is attempting in his own or her own way the same life, yet not necessarily talking about it a great deal—this felt to me like the way humans were intended to live.” But communal practice does not relieve us of the responsibility for our own individual practice. Rather, it renders that responsibility more acute. “Community coexists with the encouragement to know yourself as the sole inhabitant of your practice. No one can get up for you in the morning. No one can decide for you whether to center your attention just this moment on your spine, your breath, or the sounds coming, just now, into your ears.”

Similarly, says Hirshfield, “no one can write your poems for you.” Every poet has to find his or her own voice. For the Zen poet, versed in the Buddhist view of no-self, this task might seem like something of a conundrum. “But to have a starting place which is not centered in ego,” says Hirshfield, “does not mean that a person won’t have a recognizable, unique, particular and even—dare I say it?—authoritative voice. When the larger self comes through, it’s not going to come through as a vague mist. It’s going to come through with great clarity.” She cites the example of Dogen as “one of the most wildly free and idiosyncratic describers of awakened mind,” and that of Emily Dickinson, whose 1,776 poems “each describe a very specific, tiny fact of something, not the general.”

In a new poem from After called “The Double,” in which the private self regards the public self with tender amusement, Hirshfield describes her own experience of the self as an entity less stable and unified than we might assume:

I am tired, but she is not tired.

I am wordless;

she, who has never spoken a word of her own,

is full of thoughts as precise and impassioned

as the yellow and black exchanges of a wasp’s striped body.For a long time I thought her imposter.

Then realized:

her jokes, even her puns, are only too subtle for me to follow.And so we go on, mostly ignoring each other,

though what I cook, she eats with seeming gusto,

and letters intended for her alone I open with curious ease,

as if I, not she, were the long-accomplished thief.

Hirshfield’s poetry arises out of the painful emotions of lived experience. It speaks of loves lost, mistakes made, the discord of our many selves. But her poems are rarely autobiographical in the narrative sense. This is due in part to the practice of right speech, but it’s also because Hirshfield the Zen student doesn’t see the personal and universal in dualistic terms: “The world embraces us at every moment. And you don’t stop at your skin. To write about a tree with absolute objectivity is to write autobiography, and to write your personal story is to write the geography of the planet.”

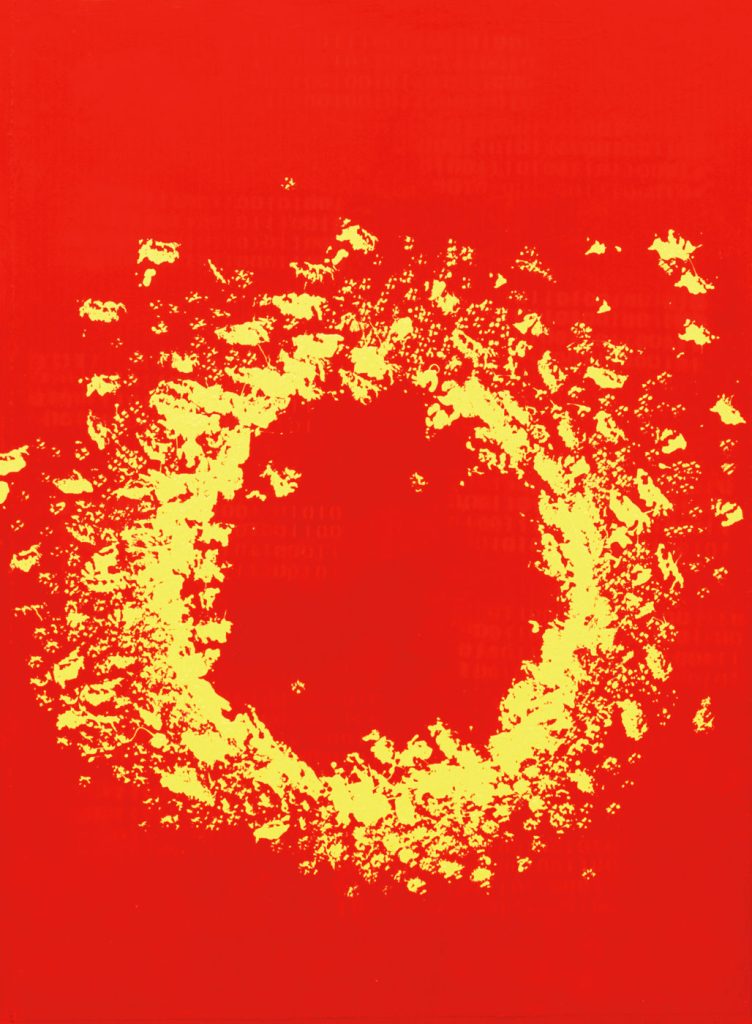

Asked if she has ever worried whether practicing toward equanimity would snuff out her need to make poems, Hirshfield says, “However my own poems have arrived thus far, I believe it’s possible for a work of art to emerge out of the sense of perfection of things as they are—surely that’s what a sumi-e circle is. Far from an abstractly ‘perfect’ circle, it includes the ragged, breathing edges and openness of the actual. . . . I suppose if I were a fully awakened being of some other kind, I’d write poems of some other kind. But it’s not so bad being a blind donkey, really, braying about, nose buried deep in the grasses of the world.” When we write from the truths we know, we can’t predict how our work may serve others. And that, Hirshfield tells us, “may be part of the bodhisattva path.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.