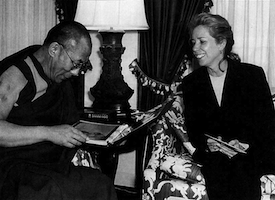

Kundun, a feature film depicting the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s early life and the events leading up to his escape from Chinese-occupied Tibet, is due for release this Christmas from Touchstone Pictures. It was shot in Morocco last fall by Martin Scorsese with an all-Tibetan cast. Writer Melissa Mathison first interviewed the Dalai Lama in 1991. Several months later, in April 1992, she traveled to India, where she discussed the first draft of the script with His Holiness. The following are excerpts from their conversation.

Mathison: We are now fifteen minutes into the movie. People have watched this boy and they need to hear the words, “This is the Dalai Lama.” So I used the scene in the tent with all the grandeur for the announcement. One other point is that in order to obtain emotional continuity between the person who’s playing the Dalai Lama and the audience, we stay with the Dalai Lama. We never go away to the auspicious assembly for the events but we stay always with the Dalai Lama, with the boy. So, even if this is not the first announcement or the most dramatic announcement, we’ve overdramatized the moment. And your parents will hear the announcement at the same time as the audience.

Dalai Lama: At the assembly, it can be stated that the Regent declared, “We are very grateful that we found the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. Now we are happy.” That kind of statement.

Mathison: May we introduce the Oracle in these dramatic circumstances?

Dalai Lama: Sometimes the Oracle became so filled with emotion that he made a prostration in front of me. We can put the Oracle prostrated in front of that small boy. That we can do.

Mathison: In this way we explain to the audience what the Oracle thinks is important.

Dalai Lama: This is not untrue, not incorrect. At that time, one famous great scholar was very much educated about the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. So when the Dalai Lama came to that tent, and the Regent was there and the Oracle, he especially went there to observe. Then he saw me and stated that now he was completely relieved of all his concern, that the Dalai Lama was the true one.

Mathison: This was the old monk with the doubt in his eyes.

Dalai Lama: Yes, that’s right.

Mathison: And we can see him again after we meet the Oracle and see that he looks satisfied or relieved and moved emotionally. So this is a big piece of work we’ve just done. And that last moment is the mother and the father reacting to the fact that their son is the Dalai Lama. We need to show how they react. We can do it all in one scene. In their faces we must see that they did not realize who their son was believed to be. Maybe that’s a little overstated; they must have hoped and felt that he was the incarnation. But now it’s done.

Dalai Lama: Maybe my parents had a peculiar experience. Because unlike other smaller lamas who were recognized, here their youngest son has now become the Dalai Lama and is completely surrounded by these officials who show great reverence.

Mathison: It was a complicated reaction. That’s good. That’s what movies are all about, complication.

Dalai Lama: A foreign dignitary, an Englishman, was there. Politically, this is very important.

Mathison: So you see that Tibet has relations independently with foreigners?

Dalai Lama: Yes. So I would like to indicate that the Englishman and the Chinese are in the same category of foreign dignitaries.

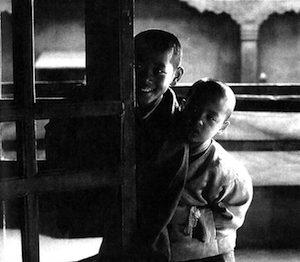

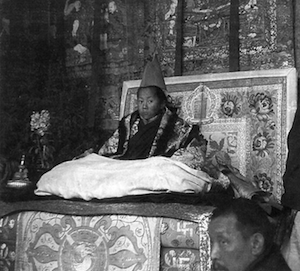

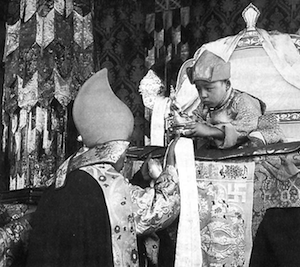

Mathison (reading from script): “We hear the sound of a great Tibetan horn. We hear peals of childish laughter and we find ourselves in the Potala. We see Lobsang and his little brother, Lhamo, soon to be recognized as the fourteenth Dalai Lama. The duo skid, slide, and skate down the endless slippery hallways in this huge labyrinthine monastery. Three monks scurry behind the boys, trying to keep the young incarnate from slipping out of their sight. They shout in large stage whispers. The boys skid to a stop in front of a large hall. Lhamo enters the great hall. The great hall in the Potala is the seat of the Tibetan government. These monastery walls are hung with beautiful old thangkas, embroidered silk hangings, depicting the life of Milarepa, an ancient spiritual master and poet. Inside the halls sit the high lamas, a cabinet of four members, officers of the government, two laymen and two monks, two prime ministers and the Regent. The Regent, Reting Rinpoche, a young man and himself the incarnation of the former Regent, bows to the young Dalai Lama as the boy runs into the room. Lhamo slows, walks to the table standing in front of the Regent and takes his place in the center of the room. The Regent hands the four-year-old boy the state seals. He shows the boy how to lift the first heavy golden seal and bring it down on the parchment. The second silver seal the boy can handle by himself. The document is stamped with the seals of the Tibetan government. The occupants of the room bow. This is the fourteenth Dalai Lama’s first official act.

“Interior—the private rooms of the Dalai Lama. Reting sits cross-legged on the floor in this dusty, dark, cold room. These are simple rooms decorated with deity scrolls and Buddhist artifacts. Behind Reting is an altar holding offerings, a small butter lamp, and a statue of the Buddha. The only other piece of furniture in the room is a bed, a large wooden box filled with cushions, draped with red curtains. Reting is speaking. We notice that he seems to have a continually blocked nose. He seems a bit distant, dreamy, but not cruel or stern. He is lighthearted.”

Dalai Lama: How did you know?

Mathison: You told me.

[Lhamo, now age five or six, is on the road to Lhasa to take his place at the Potala as the Dalai Lama. The caravan is camped for the night.]

Mathison: “Interior—tent. Night. Lhamo is very still as a monk carefully finishes cutting the boy’s hair.”

Dalai Lama: Probably my hair was cut short.

Mathison: “The monk is cutting his hair. And the monk says, ‘Do you go homeless?’ The boy looks at the monk and repeats his short memorization. ‘Yes, I go homeless.’ Lhamo is now wearing the maroon robes of a monk.”

Dalai Lama: No, still in yellow.

Mathison: So the yellow robe you wear would be just like Tibetan clothes.

Dalai Lama: Yes, that’s right.

Mathison: What I wanted to show here was the monks beginning to try to teach you to repeat, saying memorizations. And I saw that little phrase somewhere, “Do you go homeless?” And I thought it was quite a beautiful phrase, so I used it. And it may be totally incorrect. But I wanted the monk who was cutting your hair to give you a little saying that you have to repeat back. Can you think of some little phrase that would be better than that?

Dalai Lama: “I take refuge in the Three Jewels.”

Mathison: Is there another line after that? I think to help understand the process of memorization, we should have a prayer that has more than one phrase so that the monk would say the first phrase, and then the boy would say the second phrase. And they would build. We would then understand that this was a process of memorization without having to talk about it. But whatever the prayer is, when the hair is finished: “Lhamo stands and looks at the older men around him and calmly says, ‘I want my mama.’ Lhamo runs to the tent flap and pulls it open, and standing outside the tent is a bodyguard, a huge, burly man.”

Dalai Lama: Monk bodyguard.

Mathison: Okay, monk bodyguard. “Wearing sheepskins and a fur hat.”

Dalai Lama: No sheepskins. Monk’s clothes.

Mathison: Okay. “He turns to the boy. In one hand he holds a sword.”

Dalai Lama: No sword. Big stick.

Mathison: This is the man with one eye.

Dalai Lama: No, not one eye. On one eye he has a big bump.

Mathison: Okay. A fearsome-looking man. “He turns to the boy. He bows to the boy.” Would he bow to you if you were only a candidate?

Dalai Lama: Yes. This incident happened on a one-day journey from Lhasa.

[1950: the Dalai Lama, now fourteen years old, is informed of the Chinese invasion by the Lord Chamberlain.]

Mathison: “The governor reports a raid on the Tibetan radio by Chinese soldiers. General Thuthang is dead. We have one report that the Chinese have entered Tibet in six locations.”

Dalai Lama: The Indians used the words “line of actual control.” That means not the real border. The border is further east. The Chinese in the first invasion already took some area. And then in this case it’s very clear. In 1912, the Tibetan army pushes the Chinese army quite deeply into eastern Tibet. Then, in the 1920s, the Chinese army comes and push. Then, the local people consider they are the subjects of Tibetan government. But then the Chinese controlled. They continue fighting there. One British missionary came as a mediator. That was considered temporarily the border. So the Chinese invasion entered beyond that actual control area, not the real border.

Mathison: This information on the border and the control is very important for the rest of the piece. Could we create a scene where the general explains to you a little of this information?

Dalai Lama: Actually, when the officers met with me there was no exchange of words.

Mathison: This would be good to see. Maybe after the meeting, after they’re all taking their leave, you call the officer back and say: I want to know what the situation is. But it could be done with things, like when you play with toy soldiers. A strategy. It could be very educational for the audience.

Dalai Lama: That’s fine, yes.

Mathison: This information about the strength of the Tibetan army should come earlier. This happened on May 1950 and the actual invasion came in October 1950.

Dalai Lama: The important thing is that the Chinese entered Tibet on six occasions across the actual control line, not the border.

Mathison: I think we can make that clear in a previous scene with the officer, and then when the invasion happens, we’ll understand. So let’s skip down to the Dalai Lama’s room. “Interior—Dalai Lama’s room. Dusk. The boy sits alone, a small table beside him piled high with Buddhist texts. Incense smoke curls. His Holiness is meditating before the thangka. His eyes are closed, his palms lay gently open on his knees. He is quiet and still.”

Dalai Lama: Meditating means the basic Buddhist practice. So a thangka of the Buddha.

Mathison: The Buddha of Compassion?

Dalai Lama: Buddha.

Kundun, a feature film depicting the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s early life and the events leading up to his escape from Chinese-occupied Tibet, is due for release this Christmas from Touchstone Pictures. It was shot in Morocco last fall by Martin Scorsese with an all-Tibetan cast. Writer Melissa Mathison first interviewed the Dalai Lama in 1991. Several months later, in April 1992, she traveled to India, where she discussed the first draft of the script with His Holiness. The following are excerpts from their conversation.

Mathison: “He is quiet and still. Our presence feels almost like an intrusion. It shows process of mind, rather than just rest. The idea of this scene is that you’re reflecting on this information. Exterior—Norbulingka Garden. Night. A movie is being shown outside on a makeshift screen. It is Henry V. This is a treat for the sweepers, the gardeners, and the servants. Children sit on the grass, mesmerized by this incredible vision. The boy rubs his eyes wearily. He appears distracted. This line is spoken by an actor: ‘Heavy lies the head that wears the crown.’

“Interior—Dalai Lama’s room. Night. He is listening to Peking Radio. The boy tinkers with a clock as he listens. He is swiftly becoming a master tinkerer. Radio: ‘This week on the anniversary of Chairman Mao’s victory over imperialist forces in the People’s Republic of China, 80,000 People’s Liberation Army soldiers crossed the Drichu River, east of Chamdo, and began the peaceful liberation of Tibet. Tibet is in the hands of imperialist enemies of the people. The Dalai Lama, a foolish reminder of an illiterate past, is the figurehead of this autonomous region of China. Accept our help, Tibet. The people shall be free.'”

Dalai Lama: It’s technically correct. But it was never announced on the radio. Actually my brother was sent to me by the Chinese. That was in his autobiography. The Chinese asked him to go to Lhasa to try to stop the Dalai Lama from fleeing. Then, in the meantime, the Chinese came several times and brainwashed him. One official told him: If necessary, eliminate your younger brother.

Mathison: I have this scene coming up with your brother. So when we get to it, maybe you could advise us on how it happened. This is very important information.

Dalai Lama: The Regent informed me about the situation. Then he often told me that sooner or later you have to carry the full responsibility, so therefore you should be familiar with the situation.

Mathison: We should make this a private meeting.

Dalai Lama: Yes, that’s right.

Mathison: So we’ll have the Lord Chamberlain, the Regent, several other people there. “Tibetan officials have retreated from Chamdo. The Chinese forces have destroyed the heart of our defense and with the fall of Chamdo and the fall of several other cities, it appears—”

Dalai Lama: Not cities. Towns or villages.

Mathison: “’It appears that the road to Lhasa is wide open to the aggressor.’ The Dalai Lama leans forward, catching every word. ‘The Chinese troops stand waiting in the countryside while Peking demands we negotiate. There are three points we have been offered. One, Tibet must accept that it is part of China. Two, Tibet’s defenses must be handled by China. Three, all political and trade matters concerning foreign countries must be conducted through China. The Regent has decided that Tibet should agree to point number one. We can concede that Tibet is part of China, we can guarantee that the Dalai Lama’s name and authority will remain and the Tibetan government will continue to function as it is.’ The men in the room are distraught. The Dalai Lama is visibly angry at this decision.”

[The crisis with the Chinese puts pressure on the government to vest the fifteen-year-old Dalai Lama with temporal powers as a gesture to reassure the frightened populace. Authority was traditionally assumed at eighteen years of age.]

Dalai Lama: The expelling of the Chinese mission already took place before the Chinese invasion. Has that been mentioned? That was in 1948.

Mathison: It was 1948 or 1949. We will make the steps be more direct.

Dalai Lama: So this shows the Dalai Lama since young was very much anti-Chinese.

Mathison: No. Pro-Tibetan. No one will lose sympathy with a reaction to an invasion. And no one will lose sympathy with the killing of the general. It is a natural reaction and very empathetic. Very direct and simple. This is the history, the reality. This is the time of the invasion. Tibet was an independent nation. These are the words of the letter to the United Nations. “The attention of the world is riveted on Korea, where aggression is being resisted by an international force. Similar happenings in remote Tibet are passing without notice. The problem is not of Tibet’s own making, but is largely the outcome of unthwarted Chinese ambition to bring weaker nations on her periphery within her active domination.�” We need someone to speak these words in the presence of the Dalai Lama. Never can we leave the presence of the Dalai Lama.

Dalai Lama: I see.

Mathison: So it must be someone who comes and says, “Your Holiness, we are sending this appeal to the United Nations.”

Dalai Lama: Lord Chamberlain.

Mathison: “The attention of the world is riveted on Korea…”

Dalai Lama: Is that the exact words?

Mathison: It’s the exact words I found in a translation. It was not in Tibetan. It was in English.

Dalai Lama: It was originally in English.

Mathison: “Tibetans have long lived a cloistered life in their mountain fastness, remote and aloof…” The document goes on; I just stopped there. Then we should add His Holiness’s comments: “’I disagree that we accept any of the Chinese amendments. And let us consult the protective deities.’ We should add that earlier on. The Dalai Lama: ‘I disagree that I should be enthroned. I have no experience. I am not ready to lead my people.’”

Dalai Lama: Now as things become very serious, so the kashag [body of councillors] consults with State Oracle. The State Oracle has no answer for the Chinese invasion, but he states that now the time has come.

Mathison: That happens on the next page. When the Oracle said that you should assume power, did you disagree with the Oracle?

Dalai Lama: At that moment there was no decision. There was some doubt and some willingness. That situation. Then afterwards the national assembly took place and unanimously now asked me to take power. Then I answered: I have no experience. I was still young. Even the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, he was eighteen years old. I was still sixteen or something.

Mathison: Interior—Dalai Lama’s room. We watch as the boy begins his day.

Dalai Lama: At the time when I assumed the authority then the people of Lhasa composed a song of protest [against his investiture as a figurehead with no real power, and against the presence of Mao’s representative, General Chang].

Mathison: That would be good to get that song in before you leave Lhasa. “He rises and goes immediately to prostrate himself before the statue of Buddha. His Holiness stands and renews his vows. The sun rises.

“Exterior—the Potala. Day. Like a painting, the beautiful monastery fills the screen with its white walls and red roof. The chanting of the boy fades out and shouting takes over. The Chinese General Chang is shouting off-camera: ‘I hate meeting here. This tribute to the past. I demand a less formal meeting place.’ Close on the red, bulging face of General Chang.

“Interior—the Great Hall. Day. Behind the general hang the fantastic thangkas. General Chang: ‘I am not a foreigner. I refuse to be treated like one.’ The general bangs his fist on a table and sputters: ‘Imperialist, reactionary, poisonous propaganda.’ The fist again. ‘We have come to liberate you, Dalai Lama. You must begin to cooperate.’ His Holiness: ‘In Buddhism, General, liberation is always from a state that needs healing to a healed state of release to a greater effectiveness. You cannot liberate us. We can only liberate ourselves.’”

Dalai Lama: I would never say that.

Mathison: I know, I’m making you very loud. Maybe it’s the wrong approach.

Dalai Lama: I did not say these kinds of things at that time. But later I spoke quite strongly.

Mathison: Maybe you would have just a little smile?

Dalai Lama: That’s okay.

Mathison: “’You must begin to cooperate.’”

Dalai Lama: Yes.

Mathison: And then he goes on. “General: ‘I want the songs stopped.’ Songs? What songs? Again, His Holiness can barely hide his glee. Prime Minister: ‘Street songs about the general. References to his gold watch. He is right, they are quite insulting.’”

Mathison: “Interior—Prayer room. Night. The Nechung Oracle is in full trance. He is in an especially vivid and violent spin. The headdress whips this way and that, and finally he says—” But I believe what he says will have to be translated because he shouldn’t speak. This is the time that he says, “The wish-fulfilling jewel will shine in the West.” I believe it needs to be interpreted.

Dalai Lama: The time has come. The wish-fulfilling jewel will shine in the West. Or, from the West.

Mathison: From the West?

Dalai Lama: Supposedly the meaning is that the Dalai Lama is the jewel. The jewel cannot shine from Tibet. So that jewel will go to the West and from the West it will shine. The complication is in one way it looks as if the shine will appear in the West. Not in Tibet. Not that meaning. The jewel will go to the West. From there, it will benefit Tibet.

Mathison: The light will be seen in Tibet.

Dalai Lama: Yes.

Mathison: We’ll rewrite the Oracle here.

Dalai Lama: In the same period the Oracle also said something like: When there is a stream where people cannot cross, he said he would put boats there for people. In small streams, in certain areas you can walk. In a big river there is no such area. Unless you know the stream well there is no hope. Where there is no hope to cross, he will put a boat.

Mathison: A place to cross. A ford, an opportunity. What I wrote down is: “’Where there is no crossing a big river, where there are no fords, no hope of crossing, where the only hope is a boat, I will put a boat.’”

Dalai Lama: So then there are two statements that come together. They become clear. Escape and then shine. At that time, when the Oracle said this, there was no idea we would have to leave Tibet.

Kundun, a feature film depicting the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s early life and the events leading up to his escape from Chinese-occupied Tibet, is due for release this Christmas from Touchstone Pictures. It was shot in Morocco last fall by Martin Scorsese with an all-Tibetan cast. Writer Melissa Mathison first interviewed the Dalai Lama in 1991. Several months later, in April 1992, she traveled to India, where she discussed the first draft of the script with His Holiness. The following are excerpts from their conversation.

Tricycle speaks with screenwriter Melissa Mathison

Tricycle: Kundun is a story that engages the viewer at multiple levels of involvement—personal, political, spiritual. How did your ideas about the scope of this project develop?

Mathison: My original intention was to write a movie about a little boy who becomes the Dalai Lama. It’s a great story. I didn’t know anything about the history of Tibet. But as time went on I met the Dalai Lama and received permission to go ahead with the project. I learned about Tibet and I became politically active, and that changed the emphasis of the movie.

Tricycle: How so?

Mathison: I still needed it to be a real “movie” movie. It still had to be a story about a boy whose life you wanted to follow and whom you cared about. But his loss became bigger and more pervasive. It was no longer about a boy who loses his country, or even just about a people’s loss. It became a story about universal loss.

Tricycle: What is your objective for the film in terms of raising political awareness?

Mathison: It’s very dangerous to use a movie for a political agenda, or even to think that a movie can lead to political action. But in this case, I think that one can hope that if people are moved by the past, that they will moved by the present. I would love for people to leave the theater asking themselves, “Where is the Dalai Lama now? What’s happening in Tibet now? And what can I do?”

Tricycle: Where do you see the potential for positive action?

Mathison: My own personal hope is that the Dalai Lama be able to negotiate with the Chinese. That is all he’s asked for. That is what has to happen. But in order for that to happen, our government must take a stand that makes it advisable for China to agree. Which means our citizens have to become vocal and put pressure on our government to make that happen. That’s the way it’s supposed to work here, and I think it can work to help Tibet.

Tricycle: So one hope is that, given today’s political climate, the release of the film could encourage a greater degree of focus on Tibet.

Mathison: The situation in Tibet has grown worse with the reinstatement of Most Favored Nation status for China. There is no doubt that international pressure was working to make China pay attention to the world community’s opinions regarding human rights. Now they don’t have to do that anymore. There must be a motivation for the Chinese to talk to His Holiness. That motivation is going to have to come from the international community and continued pressure from the Tibetans themselves.

You know, a whole generation of Tibetans has been raised without the direct influence of His Holiness’s values of nonviolence and compassion. And if the Chinese don’t recognize the wisdom of adopting rational procedures now, they’ll have a very different situation on their hands.

Tricycle: How has your involvement in this project affected you personally?

Mathison: Anyone who went to work on this movie to just do another job came out of it with an expanded consciousness. As the movie progressed and I became politically active for Tibet and became more aware of Buddhism and became more conscious of who His Holiness is, the movie became an act of devotion on my part.

Tricycle: So the movie should make this story, these issues, more accessible to a Western audience.

Mathison: One of the greatest successes of our movie is that we’re talking about a real story in a real place with real people. You quickly forget that the people on the screen are in maroon robes carrying out ancient rituals. We didn’t create a fantasy land. Tibet will never be what it was—nobody has any illusions about that. But I think that something can be regained. And if that sentiment leads anyone to further investigate present-day Tibet, they’ll see that the devastation is still going on. It’s not too late to make a difference.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.