As Tricycle’s contact for the Dharma Directory, I had the unusual privilege of speaking with practitioners from dozens of Buddhist communities across the country in the weeks following the September 11th attacks. From my conversations and correspondence I began to get a sense of the ways in which practice had shifted as a result of the disaster—as well as the ways in which it remained reassuringly steadfast. In the end, practice was revealed to be exactly what we say it is: a matter of life and death.

In the immediate aftermath of the catastrophe, vows were renewed and communities strengthened in some unexpected ways. “Our building, along with much of the neighborhood, was closed by city directive for about a week,” writes Jonathan Ryokan Miller of the Village Zendo (four blocks from Tricycle’s office). “The day after the attacks, we sat together in Washington Square Park and joined a vigil around the fountain. Through our Internet site we established a virtual zendo, inviting everyone to sit together, wherever they were. When we were allowed back into the building, we had a Day of Reflection and Council, and then resumed our regular schedule. The zendo was filled to capacity.”

Teachers across the country rose to the occasion. In a dharma talk I attended in Brooklyn several days after the disaster, Bonnie Myotai Treace Sensei of Fire Lotus Temple gently reminded her shaken community, “In many ways, this is the moment we have been practicing for all these years.” Haju Sunim of the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple confided, “9/11 has certainly awakened people here to the great matter of life and death much more effectively than I ever could have.”

Above all, teachers called on their students to practice. According to The Mirror, the newspaper of the International Dzogchen Community, IDC practitioners “responded quickly to the [news] with Shitro practice [a Vajrayana practice to help ease the transference of consciousness] to assist the thousands of innocent people who died.”

“Practice was more helpful than discussing the event or trying to understand, reflect upon it, or philosophize about it,” related Kimberly Kaiserman of the Tibetan Buddhist Center in Philadelphia. She added that even watching TV after the attacks “became a constant practice of generating compassion.”

Weeks later, many Buddhist centers began to hold memorial services. These ceremonies, often interfaith-based, were intended to comfort and assist the living as well as the newly deceased. Some communities, like Kaiserman’s, held a traditional forty-nine-day memorial service, meant to assist the souls of the deceased into their next realm. The Tibetan Buddhist Center’s ceremony took place “on the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum, in a multi-faith ceremony which included practitioners of Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Society of Friends (Quaker), and Islam.”

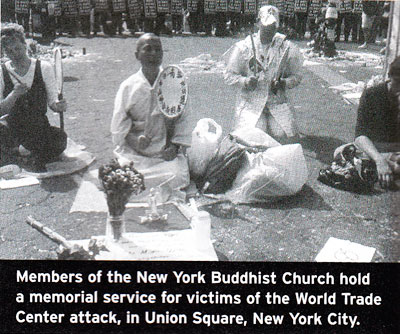

The New York Buddhist Church, a Pure Land community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, held its version of the forty-nine-day service in Union Square Park: “We began with traditional chants from ten countries, and followed [with] the main ceremony, [conducted mostly] in English,” Rev. T. K. Nakagaki revealed in the church’s newsletter, New York Kokoro. “The ceremony included music, chanting, reading, and messages… [it] finished with a peace walk with lit lanterns as I rang the gong. Over sixty monks and priests joined us and more than three hundred people gathered. It was a very special and meaningful event, especially for Buddhists in New York.”

Four months later, Buddhists groups continue to seek ways to respond to 9/11. Many communities, like the Vision Farms Meditation Center in McIntosh, Florida, have been holding meditations for world peace on a weekly basis. Vigils are ongoing at Monterey Bay Zen Center, Nipponzan Myohoji Atlanta Dojo, the Boston Engaged Buddhist Group, and elsewhere. Members of the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple are currently participating in a special practice period entitled “Be a Part of the Solution,” and subgroups of the practice period have been studying voluntary simplicity, using Thubten Chodron’s book, Working with Anger as a text (see Tricycle’s Winter 2001 issue for an interview with Thubten Chodron about the book).

“Our public Sunday services have focused on a peace vigil theme, looking at Buddhist teachings related to the events of September 11 and the following political responses,” Ch’ason Katy Mattingly told me. “We have invited persons from the community to our Sunday services to speak on the Muslim religion and globalization.” Encouragingly, even in these troubled times, humor is not lost. The Ann Arbor group will also be sending an oversized card to President Bush with handwritten notes from sangha members. One such inscription reads: “Dear President Bush, my two-year-old son says that if someone hits you, you should not hit back. Perhaps you should speak with him.” ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.