I’m not a dharma brat. This is the term that’s sometimes given to the tiny group of us who grew up in America as the children of Buddhist convert parents. Technically speaking, this title would definitely apply to me: both my parents were serious students in the Tibetan tradition of Shambhala Buddhism for years before I was born. For the first two years of my life, my father was the codirector of a large rural meditation center. My first steps were taken in a large dining hall to the loud applause of a group of American Buddhist lay practitioners eating dinner. My parents tell me I was the unofficial mascot of the retreat center. So whoever came up with the term “dharma brat” definitely had someone like me in mind.

But there’s something essentially wrong with that title. In it there seems to be a playful suggestion that, while some people have to search high and low and with great hardship to find a spiritual path that rings true to them, a “dharma brat” gets the truth spoon-fed to him from birth, even to the point of becoming spoiled by the process. But the Buddhist teachings don’t work like that. There is no truth available external to one’s own experience of it, no way to be spoon-fed the dharma as if it were a bowl of creamed carrots. It’s not even possible to be a second-generation Buddhist because there’s no way to be second-generation to your own experience. You can’t just inherit this family business. I think that is what frustrated me the most growing up: people telling me in a variety of ways how lucky I was to have been born into a tradition of wisdom and compassion. But even up through my teenage years, I could never make much connection between my ex-hippie artistic parents’ New Age church group and any sense of definitive truth that could be of use to me or anyone else in the world. I found more wisdom and compassion in exploring the vibrant, eclectic landscape of my New York City youth than I ever found sitting cross-legged in front of a shrine topped with candles and incense and visually cluttered thangka paintings and photographs of a lot of doofy-looking Tibetan men, focusing my attention on my breath and thinking to myself, “Yeah, I’m breathing.

That’s your big fuckin’ realization, my man? Good for you, Siddhartha.” Eventually, though, something began to change in my attitude.

Related: Awake with Others

Change is always more visible in looking at the endpoints of a timeline than in examining the flowing stretch in between. It’s an uneven hill, not a fixed staircase, and only through pinpoint snapshots is impermanence revealed. Recently I looked in the mirror. I was wearing a simple piece of red string around my neck, a “protection cord” I had received when I took the Bodhisattva Vow, formally declaring my intention to dedicate this life to the benefit of all sentient beings. Around my left wrist was wrapped a string of sandalwood mala beads. To top it off, dangling from a thin black cord around my neck, falling to the level of my heart center, hung a little silver pendant of Shakyamuni Buddha in the earth-touching posture. And all I could think to myself was, “Yeah, I’m breathing. What a wonderful realization!” It was at the end of a several-year-long period of thrusting myself more wholeheartedly than I ever had before into meditation practice and the intensive study of Buddhism; a year in which seven months had been spent living at a meditation center in rural Vermont—the same center where I had taken my first steps. It was the end of a period in which it had become more than clear that meditation practice wasn’t just a gimmicky relic of my parents’ hippie days, and being from a Buddhist family wasn’t just something I told girls to get them more interested in me. It was my thing now.

Related: The Bodhisattva Vows

And I claimed it as mine because it was relevant. The human Buddha and the human teachers who have followed him had something to say to me concerning the real conditions of my life, and I was ready to listen. And I was ready to listen not because of some exotic form of thought, or because of aesthetic attraction to some new set of cultural trappings, or because my parents had somehow brainwashed me, but because what was being taught informed my experience directly. The teachings resonated with me because I examined for myself, through the practice of meditation, each and every statement made about the nature of the human mind. I was finally beginning to accept that I couldn’t escape my own mind, and I was starting to see how the world around me both produced and was produced by that same mind.

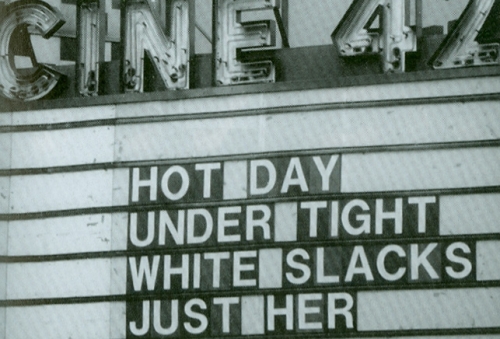

The first thing I saw when I got back to New York City after a recent retreat was Times Square. Somehow my ride went straight from the highway into the “crossroads of the world.” It was an overwhelming change of scenery. The muted winter landscape of northern Vermont was replaced without segue by a daunting urban scene without even a square inch of visual space in which the eye or mind could rest. Huge images overhung crowds of people, an advertising onslaught conveying no coherent message to no one in particular. Any straightforward effect that one digital billboard could have was instantly overshadowed by the next, leaving me with only the vague desire to consume something, anything—sex, soda, cellphones, people, information, even spirituality. It seemed like the air itself had been injected with a strange blend of caffeine and Viagra. My gaze, softened by retreat, got jittery in a hurry. In this space without space, the Pepsi logo was inextricably tattooed to Britney Spears’s breasts, and Britney Spears’s breasts were in turn tattooed to the insides of my eyelids.

The second thing I saw when I got back to New York City was a group of young people protesting. It was the weekend of the World Economic Forum in New York, a group of international business representatives meeting privately at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel to discuss economic matters directly affecting our entire world. Traffic was snarled, and sirens sounded everywhere as our car approached Lower Manhattan’s East Village. From time to time, huge vans full of cops in riot gear sped past us. After a long traffic jam, we saw the source of the disturbance.

On a Village street, a small group of young people, mostly in their twenties, were marching, miles away from the event they were protesting. For every protestor, about two police officers flanked the group, walkie-talkies on and batons ready, apparently waiting to pounce if any of the demonstrators broke formation. For a moment I thought it was the cops who were marching, because they outnumbered the demonstrators. The energy of the scene was confused, sad, impotent. There were no clear messages being articulated, no hopeful voices to be heard, and definitely no chance for fruitful dialogue between those charged—ideally—with protecting our society and those charged—ideally—with carrying our society forward with compassion, energy, and vision. It was just a large group of angry cops set against a tiny group of what seemed to me to be privileged but disempowered kids, both groups left to mutter furious clichés about making the world a better place while chasing the ghosts of their own aggression down a city street.

It took me a few months of being back in New York to think about what I’d seen, about why so much visual energy had been compressed into my first twenty minutes back “in the world.” Times Square is a huge visual minefield of ads primarily targeted at an audience between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four, teenagers and young adults being the most impressionable in their habits of consumption. But there is another Times Square—the one inside my mind, the one that meditation practice is helping me get accustomed to. This is the Times Square where all ads are placed by subsidiary companies of the imaginary Mega-Multinational Corporation called Ethan’s Hopes and Fears, Inc. What a devastating place my own Times Square is, and what a place to be stuck as a permanent tourist! I remembered what meditation meant to me, why I now claimed it as relevant to my own life. It was a tool of empowerment in the face of all the flashing billboards, both internal and external. It was the way I could begin to look at the space of my mind—to see what amorphous products I was trying to buy and sell, what fixed notions of identity were being hammered out in my dungeon sweatshops, what digital fantasies were getting me high and horny.

I could return to that space over and over again with a useful tool at my disposal. By returning to the space of my mind repeatedly, I could begin to see it for what it was. And by seeing it, I could begin to see through it.

Then I thought about the young protestors I had seen. There’s a very definite link between the meditator and the protestor. Both are acting from the genuine inspiration to help a world they must love dearly. Both are willing to look out the window and see the suffering in that world. Both are willing to take a look at the causes and conditions of our world, and to call into question the confused, materialistic forces that built Times Square. But the meditator may have a tool the protestor often lacks. This tool is a method of practice in which one refuses to externalize the truth of suffering as somebody else’s fault or problem; the training is to always bring our focus back to the causal link between our internal Times Square and the external Times Square. With this attitude, we cannot demonize anyone in particular, because we see that they are as confused as we are, that they live under the same basic conditions. How can we stay mad at someone who’s subject to the same basic conditions—and even claim righteousness in our anger?

I think I’ve felt a lot of shame about my existence. I’ve been completely privileged by the circumstances of this human life without feeling much power to affect the course this world takes. I don’t think I’m the only person in America who feels this way; I’m definitely not the only young person who feels this way. In my heart, a deep sadness is mixed with joy and optimism in one big fat sushi roll of ambivalence. I’ve concocted so many ways of trying to sweet-talk this ambivalence into some form of comfort instead of just facing it.

At times I’ve given up and become complacent in hopelessness, searching for creature comforts wherever I could, even though I’ve seen countless hints in my own life that this way of relating to existence is ultimately like trying to lick honey off a razor blade. I’ve even convinced myself there is something exquisite about the image of licking honey from a razor blade. Sometimes I’ve been bitter and angry instead and looked desperately for someone and something to blame, only to find my bitterness turning on myself. Sometimes I’ve done both—settled for material comfort and gotten angry at the “system”—only to discover my own inescapable hypocrisy. Sometimes I’ve even celebrated my inescapable hypocrisy. Usually I’ve done all these things in a single day.

No matter what my response is at a given moment, the practice of meditation has been there, like a pristine, unadorned mirror. It looks at all these mental attitudes like more grist for the mill; it chews on them and never gets full from bullshit. Every time I bring something to the practice, it answers, almost as if it were an external entity: “Oh, that’s where your head is at right now, Ethan? Good, bring it on, we can work with that.”

The power of meditation practice doesn’t stop there, though. It lends insight—through repeated glimpses that slowly increase in clarity—into the connection between the way our minds are constructed and the way our world is constructed. When I question whether it’s possible to have a less confused mind, meditation answers with a head-banging Yes. When I question whether it’s possible to share a less confused world, meditation answers with a heart-thumping Yes. Personally, I want to learn how to perceive with that mind and how to act for the benefit of that world. That’s why I’ve chosen to become, like my parents did before me, a first-generation student of my own mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.