In 1959, the little-known 14th Dalai Lama fled his homeland as China’s army invaded Tibet. Just over a decade later, a generation of young Western seekers encountered Tibetan culture for the first time. Among them was Stephen Batchelor, who looks here at the story behind the Tibetan diaspora, what it has meant for Buddhism in the West, and what the future may hold.

Some years ago I strolled into a diner off West Houston Street in New York for a quick lunchtime sandwich. The manager, a burly middle-aged Italian-American with a bouffant hairdo, sat on a stool by the cash register in one corner. On the walls around her were pinned colorful posters of Tara, Avalokiteshvara, and other Tibetan Buddhist deities as well as several photographs of a beaming, namaste-ing Dalai Lama. As I was paying for my meal, I asked why she had all these images around her. “It’s him,” she pointed to a picture, “the Dolai Lamma. I was in Central Park last summer. He was talking to this crowd of people. Then someone asked: ‘Who’s been your most important teacher?’ And he answered— without missing a beat—‘The Chinese. They have taught me the most.’ That really touched me.”

I suspect that for many Americans like this woman, the most Christlike figure alive today is not a Christian but a Buddhist: Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. For here is a man who has undergone unimaginable loss and hardship but who appears to bear no grudge against the people responsible for invading his country, desecrating its ancient culture, and forcing him into an exile that he has now endured for fifty years. He seems to embrace the Chinese occupiers with equanimity and kindness, to see them as suffering people rather than ciphers of a hostile nation, to regard them not as foes but as valued teachers who enable him to cultivate tolerance and compassion. And the more one observes the Dalai Lama as he travels the world, whether meeting presidents or addressing vast crowds, one starts to realize that this is not political or religious posturing, a cynical tactic designed to gain sympathy for his cause. This is the real thing: a man who cultivates and embodies the values he champions.

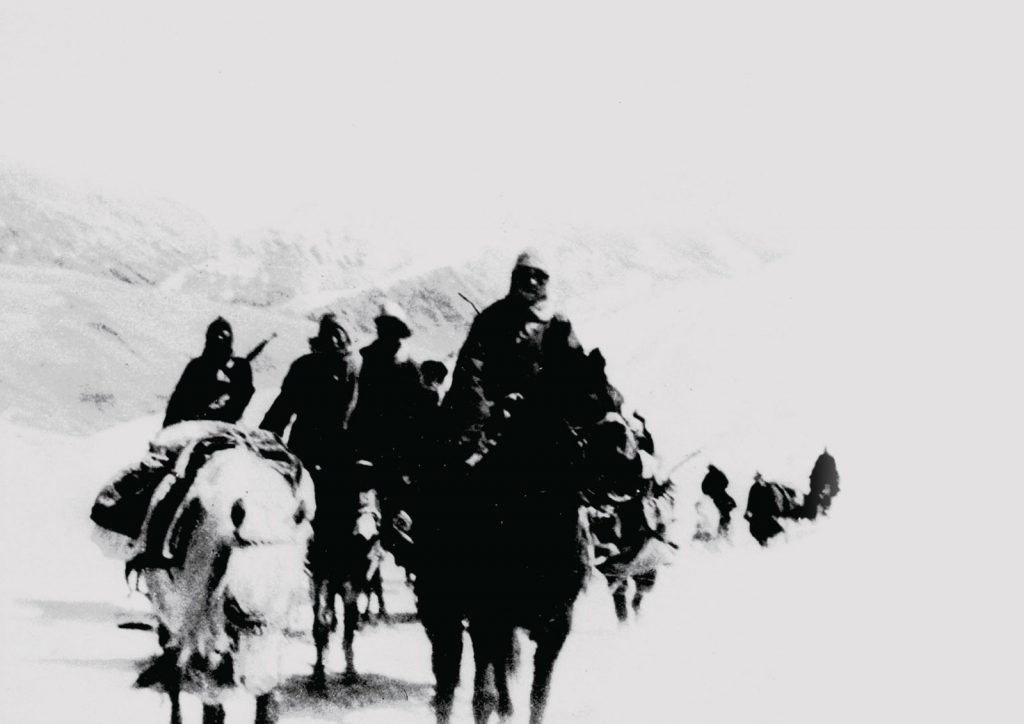

When I arrived in Dharamsala in 1972, the Dalai Lama and his followers had been in exile for 13 years. They had fled their beloved country in the wake of a failed uprising against the Chinese occupation in March 1959. With little more than the clothes on their backs, they escaped over the high mountain passes into Nepal, Bhutan, and India to begin life as refugees in some of the poorest countries in the world. When I first met him, the Dalai Lama was a young, energetic man of 37, full of good humor, faced with the daunting task of resettling 100,000 Tibetans in India and establishing a functional government-in-exile. Despite the enormous tragedy that had befallen them, the Tibetans I knew tended to be upbeat. These proud, resilient people found it hard to imagine that their exile could last for much longer.

From the perspective of common sense, Tibet is a country just like Italy or Japan. It possesses a rich and complex culture with a long history, its own language and literature, a highly distinctive religion and a unique form of government. So why, one might reasonably ask, is it not welcomed into the family of nation-states and given a seat at the U.N.? Why should recently concocted political entities such as Pakistan or Israel be accorded full recognition as nation-states, whereas Tibet is not? Why, in the past 50 years, has not one single government recognized the Dalai Lama’s government-in-exile? And why should a people who have never for a moment thought of themselves as Chinese be regarded as Chinese citizens? It all seems terribly unjust.

From a modern historian’s point of view, Tibet operated as a fully independent political state for only a relatively brief period, from the seventh to ninth centuries C.E., when the kings of the powerful Yarlung dynasty unified the Tibetan plateau and even briefly occupied Chang-an (Xian), then the capital of China. The subsequent regimes that ruled the whole of Tibet were installed by either Mongolian or Manchurian armies, whose leaders were also emperors of China. Since the most powerful figures in Tibet at these times were Buddhist lamas, their secular backers appointed them as rulers of Tibet. As a far-flung province of Imperial China, Tibet was of little interest to the emperors, and the Tibetans were left to rule the country as they wished. Under these conditions, Tibet was free to develop its unique buddhocracy. Starting in the early 18th century, China nonetheless retained a symbolic presence in Lhasa in the form of an amban, or governor, and a small contingent of troops.

A Buddhist monk cannot engage in war, not even in self-defense. The security of Tibet was thus vouchsafed by China, which occasionally sent in troops to repulse invaders. The relationship between China and Tibet was defined in such a way that each side could perceive itself as the dominant partner. While the Chinese government saw Tibet as an integral part of the realm (a view still held by most Chinese today) and thus subordinate to the emperor, the Tibetans regarded their high lamas as the teachers of the emperor, thus rendering him subordinate to their spiritual authority. This “priest-patron” (chö-yön) arrangement was modeled on the traditional relationship between a Buddhist monk and his lay benefactors. The relationship between China and Tibet was thus one of interdependence, with each party depending on the other for what it could not provide for itself. Such a model, which was informed by Buddhist ideas of not-self and dependent origination, had little room for such dubious notions as “independence”—a term that Tibetans did not use to describe their status as a nation until the 20th century.

Unless cataclysmic political changes occur in Beijing, Tibet now looks as though it is on its way to becoming the New Mexico of China.

After the collapse of the Chinese Manchu dynasty in 1911, the Tibetans, under the leadership of the 13th Dalai Lama, evicted the amban and his troops from Lhasa and embarked on a period of de facto independence that lasted until the invasion of Tibet by the People’s Liberation Army in 1950. However, this period was too brief and troubled for the Tibetans to be able to consolidate their independence. Internal feuding, the death of the Dalai Lama in 1933, reluctance of the monastic authorities to embrace reform, and a failure to establish international recognition for their regime, all meant that the Tibetan government was unable to resist the invading forces of Communist China. Unlike the previous emperors, Mao Zedong rejected religion as “poison” and had no intention of deferring in any way to the Dalai Lama of Tibet. The rules of politics in the Middle Kingdom had changed. The “patron-priest” relationship was redundant. The Tibetans joined the Armenians, Kurds, and Palestinians as another stateless people, their aspirations thwarted by a new geopolitical status quo against which they were powerless to act.

On October 17, 2007, in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C., President George W. Bush presented the Dalai Lama with the Congressional Gold Medal for his work in promoting peace and human rights. Predictably, this prestigious endorsement of the exiled Tibetan leader brought howls of protest from China, who accused the Americans of meddling in its internal affairs. While the award ceremony raised the international profile of the Dalai Lama to even dizzier heights, it was a generous but hollow gesture by an unpopular president who may have stood to gain more from his public association with the Dalai Lama than the Dalai Lama could ever hope to gain from him. For despite all the handshakes, smiles, and noble sentiments, the award was not accompanied by a single concrete act in support of the Tibetan cause. Arguably, this kind of event only gives unrealistic expectations to Tibetans and hardens the attitude of the Chinese, who understandably resent being depicted as the evil oppressors of one of the world’s favorite good guys.

When I arrived in Dharamsala in 1972, the Dalai Lama was a little-known, politically isolated figure who had not yet been able to set foot in the West. This was the year in which Richard Nixon made his famous visit to Beijing to meet Mao Zedong and begin the normalization of relations with China. What little covert support the Americans had been giving to Tibetan guerrillas in Nepal was cut off. Since his flight to India, the Dalai Lama had had to listen powerlessly as news of the destruction of Tibetan culture at the hands of the Red Guards trickled out of his homeland. He continued to be refused entry into America until 1979, twenty years after his escape from Lhasa, when the Carter administration finally granted him a visa.

Throughout the 1980s the Tibetan cause gained increasing international recognition, largely through the Dalai Lama’s tireless efforts on its behalf combined with his growing stature as a global spiritual leader. In 1988, in a speech to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, he declared that he no longer sought independence for Tibet but only meaningful autonomy within the People’s Republic of China. This amounted to a tacit recognition of the status quo that had existed between China and Tibet for centuries, a point lost on many of his more enthusiastic supporters. In any case, the Chinese ignored him.

The following year the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which further angered the Chinese by consolidating his position in the eyes of the world as a man of unimpeachable integrity and compassion. This growing public support for Tibet was a factor in Bill Clinton’s campaign promise in 1992 to link the granting of “most favored nation” (MFN) trading status to China with “overall significant progress in human rights.” In May 1994, however, Clinton abruptly withdrew this condition. The reasons were economic. The message to the Chinese was clear: stock markets in Hong Kong and jobs in Delaware will always count for more than the rights of oppressed minorities elsewhere in the world.

In 1989, the Dalai Lama turned down an invitation to officiate at the funeral ceremonies in Beijing for the recently deceased Panchen Lama, which would have provided him with the first chance for face-to-face political discussions with the Chinese leadership. Although his refusal may have been at the insistence of his advisers in Dharamsala (Tibet was then under martial law), in retrospect it looks like a misjudgment. Since then, despite continuing worldwide sympathy for their cause, the Tibetan exiles have received no further conciliatory gestures from the Chinese. Meetings continued to take place behind the scenes between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and officials from the Chinese government, but they led nowhere. Although China would doubtless enjoy a surge of global goodwill were it to make even moderate concessions to some of the Dalai Lama’s demands, a totalitarian government of more than a billion people cannot be seen to kowtow to the ambitions of 100,000 exiled Tibetans and their vociferous Western champions. Any gains for the “Dalai clique” would inevitably be seen as a humiliating step-down for China.

The encounter between Tibet and the counterculture of the 1960s was like a midair crash between two sets of conflicting desires. The Tibetans were escaping from Chinese Communism; we hippies were running away from the military-industrial complex. We were both exiles, fleeing in opposite directions. We collided over India like particles in an accelerator. Neither side really understood or appreciated the needs of the other. We looked to the Tibetans for the lofty insights of Buddhism to help resolve our existential anxieties; they looked to us for the support they needed to survive as refugees in an uncomprehending and hostile world.

Half a century later, the Tibetans still have not regained their country, but Tibetan Buddhism is on its way to becoming a world religion. In the early 1970s, those of us in Dharamsala would have dismissed as a fantasist anyone who suggested that the Dalai Lama would become a household name in Nebraska and “America’s Fascination with Buddhism” would be featured on the cover of Time magazine. When non-ethnic Buddhist centers in America could still be counted on the fingers of one hand, it would have seemed inconceivable that today retreat centers, temples, monasteries, and sanghas would number in the hundreds if not thousands. At a time when it was still possible to have read every dharma book in English, it would have seemed absurd to suggest that within a couple of decades you would be unable to keep up with those published every month. Without the tragedy of the Tibetan diaspora, Tricycle magazine would almost certainly not exist, and I would not be writing this article.

Although Buddhism in America also has its sources in Southeast Asian, Chinese, and Japanese traditions, the sudden exodus of monks and lamas from Tibet was, I believe, the single most important catalyst in stimulating Western interest in the dharma. Because of its physical isolation and unique sociopolitical organization, for centuries Tibet had been able to preserve intact a complete form of late Indian Mahayana Buddhism, and because they were exiled from their homeland, Tibetan lamas had little choice but to find ways to survive in the wider world. Their success in establishing centers across the globe has been such that other traditions of Buddhism have sometimes been eclipsed by the presence of Tibetan forms of the dharma; in the public eye, the Dalai Lama has even come to be mistakenly regarded as a sort of pope revered by all Buddhists alike.

China has changed a great deal since 1959. The bad old days of the Cultural Revolution are long past. An unprecedented number of Chinese citizens are experiencing a material prosperity that their parents could only have dreamed of. Traditional religions such as Buddhism are no longer suppressed. Monasteries are functioning again. People are allowed to travel abroad and have limited access to the internet. The Chinese government may still impose harsh constraints on individual freedom and ruthlessly quell dissent in Tibet, but voices of change are beginning to be heard. On December 10, 2008, Charter 08, a document calling for wide-ranging reforms, was signed by more than two thousand Chinese living within China. Two days later, the Dalai Lama issued a letter in which he gave his full support to the document. In the long term, the Tibetans may be in a stronger position to achieve their political goals by working alongside dissidents for reform within China rather than focusing on the sole issue of independence or autonomy for Tibet.

If the Dalai Lama is ever to go back to Tibet, the first step would have to be a symbolic return to China. There might come a point when leaders within the Chinese government decide that they would gain more by having the Dalai Lama on their side rather than criticizing them from abroad. Ideologically, this should present no problem. “I am a Marxist monk,” the Dalai Lama reiterated several times in a speech in India on January 18, 2009, “a Buddhist Marxist. I belong to the Marxist camp, because unlike capitalism, Marxism is more ethical.” (This makes him the first Marxist to receive the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal.) There is no reason the Dalai Lama could not be invited to make a pilgrimage to Wu-tai Shan, the five-peaked mountain of Manjushri, sacred to Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian Buddhists alike. Not only has the Dalai Lama himself expressed the wish to do this, but such a visit would also allow the Chinese to stage a series of religious events presided over by the world’s most recognizable Buddhist without explicitly having to acknowledge the political issue of Tibet.

But it may already be too late. Paradoxically, the Dalai Lama’s extraordinary success in establishing himself as an iconic figure on the world stage might be the greatest obstacle to his ever returning to his homeland. As Patrick French has written in his sobering book Tibet, Tibet, “The Dalai Lama has come to represent too much; his return to Tibet, with the world’s media traveling in his wake, hoovering up the biggest story of its kind since Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, would be profoundly destabilizing to Communist rule.” The Chinese authorities would have to be prepared to deal with the consequences of 50 years of bottled-up emotion among millions of Tibetans being unleashed as soon as the Dalai Lama set foot in Lhasa. As things currently stand, this is not a risk they would be likely to take.

Unless cataclysmic political changes occur in Beijing, Tibet now looks as though it is on its way to becoming the New Mexico of China. It must be puzzling for the Chinese to be criticized for their treatment of Tibetans by a nation that little more than a century ago was slaughtering its own native peoples and confining them to reservations. With what moral authority, they might wonder, can those who enjoy their comfortable adobe houses in Santa Fe denounce the population transfer of Han Chinese to Central Tibet? The tragedy of Tibet offers Americans a mirror image of their own bloodstained past.

From the perspective of small stateless nations, nothing much has changed since the 19th century: the imperial powers still treat them as pawns in a great geopolitical game. Occasionally, should it suit the needs of public opinion, the Dalai Lama may be granted a few crumbs from the table of the rich and mighty. But should Tibetans in Tibet have the audacity to protest at the injustice inflicted upon them, they will be crushed, and no one will go to their aid.

As I write, Tibet is preparing itself for the 50th anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s flight to India. The Chinese regime has announced that March 28 (the day in 1959 when the Communist Party officially dissolved the Dalai Lama’s government) will be celebrated as a new public holiday called “Serfs’ Emancipation Day.” They have also forbidden all foreigners from visiting Tibet during March in order that no outsiders observe whatever repressive measures they may employ should demonstrations break out again as they did in March 2008. The center of Lhasa remains under heavy police security in preparation for any unrest.

International support for the Chinese government, however, continues to grow. On October 29 last year, the British Foreign Secretary declared in a written statement that his government no longer accepted the “outdated concept of suzerainty,” which had framed British policy toward Tibet since the beginning of the 20th century. (“Suzerainty” is a term used to describe the relations between a ruling power and its vassal states, thereby preserving, albeit tenuously, the idea of Tibet’s statehood.) “Like every other EU member state,” he went on, “and the United States, we regard Tibet as part of the People’s Republic of China.” For the exiled Tibetans, this severing of the last strand of official recognition must have felt like a slap in the face. The following month, the Chinese unilaterally cancelled the rounds of talks with the Dalai Lama’s representatives that had started before the Olympics, thereby bringing to a halt what the Foreign Secretary himself called “the only forum in which there is any realistic possibility of progress to resolve the differences between the parties involved.”

Meanwhile, a recent report by the U.S. State Department noted that the Chinese record on human rights, specifically the repression of minorities in Tibet, had worsened in 2008. “Not only will we seek to live up to our ideals on American soil,” wrote the new Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in the foreword, “we will pursue greater respect for human rights as we engage other nations and people around the world.” Yet despite these fine words, on an official visit to Beijing in February, Clinton chose to strengthen ties with China on the grounds that concern for such issues as human rights in Tibet can’t be allowed to “interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis, and the security crises.… We have to have a dialogue that leads to an understanding and cooperation on each of those.” Plus ça change…, as the French would say: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.