Sometime during the cold dark night of February 22, 1937, four trucks from the Ministry of Internal Affairs (NKVD) pulled up outside the nondescript boardinghouse next to the Tibetan Buddhist temple on Primorski Prospekt in the north of Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Four plainclothes officers positioned themselves around the building while a gaggle of others marched inside to arrest Ostov Budayev, a Buryat-Mongol lama. Budayev was bundled into the back of a truck and ordered to squat on the floor. After rounding up the night’s remaining quota of political subversives, the trucks returned to the NKVD building on Liteinyi Prospekt and packed Budayev into an underground cell.

On August 29, 1937, after six months of interrogation and torture, Ostov Budayev was charged and convicted with offenses under article 58 of the criminal code, subsections 1a (treason to the Motherland), 8 (terrorism), 9 (sabotage), and 11 (belonging to a criminal organization). That night he was taken to a basement room soundproofed with mattresses and shot at point-blank range in the back of the head. While his body lay in the morgue, his blood, merged with that of many others, was drained out of the building into the adjacent river Neva. Moments later, specially assigned boats churned it up with their propellers so that citizens going to work that day would not be unduly alarmed. The following night, the corpse was covered with sackcloth and packed into another truck, which trundled across the river and out of the city to the suburb of Levashova, where the body was tipped into a mass grave and concealed beneath lime and earth.

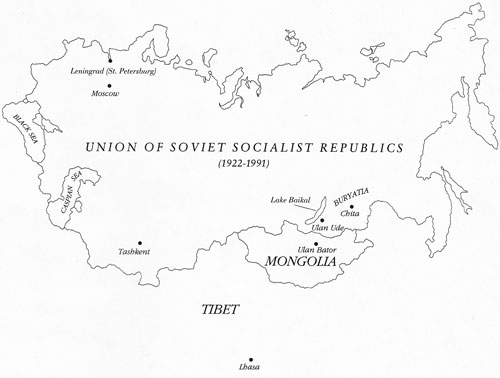

Although a Soviet citizen, Budayev was ethnically a Mongolian from the outlying republic of Buryatia, an area around Lake Baikal in eastern Siberia. The Buryat are a nomadic Mongol people who for centuries have tended their flocks on the steppes to the east of Lake Baikal. During the expansion of imperial Russia in modern times, this culture, like many others, was inevitably engulfed by the empire. Buryatia submitted to the rule of the Russian tsar in the late seventeenth century and was formally incorporated in imperial Russia in 1728. Only fourteen years earlier, in 1714, it had received its first mission of Tibetan lamas, who converted to Buddhism most of the population in the eastern part of the province, which until then had been rooted in traditional shamanism. In 1741, the first two monasteries were founded in the region and Empress Elizabeth Petrovna officially recognized a Russian Buddhist Church. This, during the reign of the Seventh Dalai Lama, was to be the last major movement of Buddhism from one country to another until modern times. From then on, a tradition was established for promising young Buryat monks to travel to Drepung Monastery in Lhasa to receive their religious education. Whether Budayev himself trained in Drepung is unknown. He was invited directly from Buryatia to Leningrad in 1930 by his teacher, Agvan Dorjiev (1854-1938), the founder of the Buddhist temple, to work as a painter of religious art.

The year 1937 marked the high point of Stalin’s purges and the second wave of arrests to befall the Buddhist monks in Leningrad. The first, in May of 1935, had been relatively mild. The seven convicted at that time were sentenced to three to five years’ hard labor in Siberia. But the six arrested in 1937, were, like Budayev, simply shot. Only one resident of the boardinghouse survived: a layman called Dylykov, who, unknown to the others, was employed by the NKVD. After the lonely death in Buryatia of Agvan Dorjiev the following year, Dylykov “donated” the temple to the city authorities, who declared it a rest home for the workers of Leningrad.

While Stalin was ridding Russia of its Buddhist monks, he made sure that the Leningrad Buddhologists suffered a similar fate. The Buddhology that flourished during this time was characterized, largely through the towering figure of Fyodor Stcherbatsky, by an attempt to combine the Western rationalist approach to Buddhism with the traditional methods of teaching preserved in India and Tibet. Stcherbatsky had visited India and had studied with the native pundits to learn their methods. His philosophical interests, however, turned him increasingly to Buddhism, and he began seeking out lamas. Although he was twice invited to Tibet by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, for political reasons the foreign ministry in St. Petersburg refused him authorization to travel. Nonetheless, as a Russian he had access in his own country to lamas trained in the great universities of Lhasa. Through Agvan Dorjiev, Stcherbatsky established contact with the monasteries in Buryatia, and both he and his students were able to study directly with the geshes (masters of Buddhist learning) there.

Around five hundred Leningrad orientalists were either imprisoned or executed during the purges of the 1930s. Rounded up with them was a young Buryat-Mongol called Bidiya Dandaron, a student of aeronautical engineering, who, with Dorjiev’s recommendation, also attended lectures at the Oriental Institute. Fortunately, Dandaron was too young and inexperienced even for the imaginative NKVD to accuse him of the kinds of crimes imputed to Ostov Budayev and the orientalists. He received only ten years’ hard labor.

Born in December 1914, Dandaron was the son of Dorje Gabzhi Badmaev, a Buryat poet, philosopher, and yogin who was a disciple of one of the most prominent lamas of his day, Lobsan Sandan Tsedunov (born c. 1850 in Buryatia; disappeared c. 1924). Tsedunov had entered the local Kizhinginski Monastery in eastern Buryatia as a young man, quickly rose to the rank of geshe, and was sufficiently esteemed to be included in an official Buryat Buddhist mission to St. Petersburg and an audience with Alexander III (reigned 1881-1894). But once ushered into the palace, Tsedunov refused to bow before the emperor of all Russia. He was not only immediately evicted but was also condemned by his fellow Buddhists.

Shocked, he forsook his vows with the declaration that “monasteries are samsara,” and retreated to a small wooden hut in a remote forest in Buryatia to begin a 30-year contemplation of the tantric deity Vajrabhairava. By 1906, long hair and beard now replacing his shaven scalp, Tsedunov declared himself a follower of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism and began to accept disciples, among whom was Dandaron’s father.

Shortly after his birth the young Dandaron was recognized as the reincarnation of Tsedunov’s teacher, Hambo Lama Jayagsy Gegen, a former abbot of Kumbum Monastery in eastern Tibet. But when, according to tradition, a delegation arrived from Tibet to take him back to Kumbum, Tsedunov refused to let him go. Then in 1917 the revolution broke out. The following year, taking the Bolshevik policy of land redistribution literally, Tsedunov’s followers declared him dharmaraja (dharma king) of a Buddhist state comprising 400 farmsteads on the steppe of the Kizhinginski Valley. Such action was the policy of the Balagat (Nomadic) Movement, of which Tsedunov was cofounder. One of the movement’s central aims was to remove the focus of spiritual authority from the monasteries by establishing lay communities based on Buddhist practices such as mahamudra and dzogchen. The Bolsheviks, however, did not share their ideals, and Tsedunov was quickly imprisoned. The community was forced underground, and in July 1921, proclaimed the seven year-old Dandaron as the successor of Tsedunov. Tsedunov was released from prison in 1922, only to be banished far from his homeland. He was last heard of in 1924. One witness claims to have seen him dressed in European clothes boarding a train for Italy.

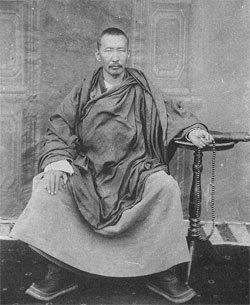

Not all Buryat lamas agreed with the tantric, lay approach to Buddhism advocated by Tsedunov and later by Dandaron himself. Foremost among these was Agvan Dorjiev, the founder of the St. Petersburg temple, who devoted his life to preserving monasticism and the Gelugpa tradition of rigorous Buddhist studies.

In 1880, at the age of twenty-six, Dorjiev was accepted in Drepung Monastery. Within six years he became a lharampa (the highest ranking geshe) and was appointed as a religious advisor to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, a post he held for the next ten years. It was not long before he assumed the additional role of lobbyist for the imperial Russian cause. Convinced that the British were preparing to “devour” Tibet, he explained to the head lamas how Russia was not only Britain’s enemy but also a place where, in Buryatia and Kalmykia (another Mongol republic in the lower Volga region), Tibetan Buddhism flourished. But this political maneuvering upset other factions in the government, and in 1897 the Dalai Lama recommended that Dorjiev take a three-year leave of absence.

Upon returning to Buryatia, Dorjiev was immediately summoned to St. Petersburg. This resulted in an audience with Nicholas II in 1898, when a possible Russian role in Tibet was discussed. The following year he was back in Tibet, his position enhanced by the sanction granted him by the tsar. As Dorjiev saw it, the Tibetan government was now split into three factions: those still loyal to the Manchu emperor of China; those who feared the collapse of the Manchu dynasty and proposed closer ties with Britain; and those (like himself) who preferred an alliance with Russia. Persuaded by Dorjiev’s arguments, the Dalai Lama prepared an official letter and gifts for the tsar and sent his emissary once more on his way.

By this time, Dorjiev’s involvement in the “Great Game” had placed him firmly in the sights of British Intelligence, who failed to share his enthusiasm about a Russian presence along the north Indian border. Nonetheless, he traveled back to Russia via India, disguising himself as a pilgrim and staying somehow one step ahead of the British. He met the tsar at Yalta, presented him with the Dalai Lama’s letters, then hurried back to Lhasa via Mongolia with the tsar’s reply. By the time he reached Odessa, his stature was such that he was escorted to St. Petersburg as a virtual ambassador.

Dorjiev did not return to Tibet again until 1904, by which time events had spun out of his control. The British, under Colonel Francis Younghusband, were preparing to enter Tibet by force to demand a trade treaty with the Dalai Lama. In April 1904 they had reached Gyantse and were preparing to march on the forbidden city of Lhasa. On Dorjiev’s advice, the Dalai Lama decided to flee. One morning before dawn, a small party of eight—including the Dalai Lama and Dorjiev—left Lhasa and made their way to the safety of Urga (modern Ulan Bator), the capital of Mongolia. The Tibetan government, meanwhile, signed the trade agreement.

Dorjiev was to see Tibet only once again. In 1912, he traveled from Buryatia to meet the Dalai Lama in the southern Tibetan town of Phari. Although the reappearance of Dorjiev sent tremors of apprehension through the British, he bore only a letter of good wishes from the tsar. As a parting gift, before he took his final leave for Mongolia, the Dalai Lama gave him 50,000 silver pieces as a donation to the temple that he had recently received permission to build in St. Petersburg.

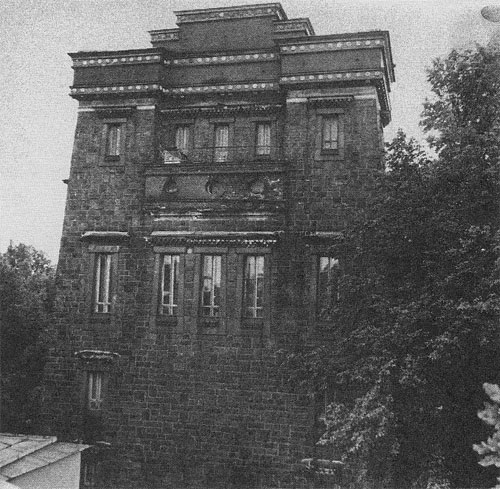

In spite of virulent objections from the Orthodox Christian Church, the temple was consecrated finally in 1915. Dorjiev managed to acquire the services of one of the foremost architects of the day, Gavriil Vasilyevich Baranovsky, to actualize in European architectural terms his own ideas for a Tibeto-Mongolian-style building. The temple was dedicated to the tantric deity Kalachakra. Sufficient monks were installed to conduct the bimonthly monastic confessional and to observe the annual Rains Retreat, thus making it the first functioning Buddhist monastery in a European capital.

St. Petersburg at this time was a center of spiritual and scholastic ferment. Theosophist followers of Madame Blavatsky were active, as were disciples of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy. G. I. Gurdjieff held groups in the city, attracting to his circle intellectuals such as P. D. Ouspensky. Yet apart from a few European faces in group photographs taken on the steps of the temple, there is little evidence of European involvement in the practice of the Gelugpa Buddhism that would have been taught by Dorjiev and his monks. The temple primarily served the religious needs of the sizable Buryat and Kalmyk communities of the capital. Serious interest among European Russians was limited, it seems, to the Buddhologists at the Oriental Institute.

Although the Bolsheviks took to suppressing Christianity after the outbreak of the revolution in 1917, it took them several years to work out an official policy for Buddhism. Since the Marxist critique of religion was essentially a refutation of Christian theism, it was unclear exactly what a good party member should think of the Buddha’s dharma. The situation was further compounded by the practical need to win the sympathy of the Buddhist populations of the nascent U.S.S.R. to the Soviet system. Dorjiev’s political shrewdness again came to the fore: taking advantage of this ambivalence, he argued that Buddhism and Communism, with their common emphasis on a nontheistic, rational, and altruistic philosophy of life, were perfectly compatible.

In retrospect, the 1920s were for the Buddhists of the Soviet Union a period of renaissance and calm before the blunt instrument of Stalinist repression crushed them in the 1930s. Under Dorjiev’s leadership new monasteries were built in both Buryatia and Kalmykia. In January 1927 a Congress of Soviet Buddhists was held in Moscow. Speakers emphasized the similarities between Buddhism and Communism and even sent a letter to the Dalai Lama praising Soviet policy. Some of Dorjiev’s more enthusiastic followers proclaimed that the spirit of the Buddha animated Lenin and that the Buddha rather than Marx was the true founder of Communism.

The turning point came in 1929, when Stalin, having consolidated his power, embarked on the repressions and purges that, by his death in 1953, were to have claimed the lives of as many as thirty to forty million people. Henceforth, Buddhism was viewed as just another weapon of oppression used by the unscrupulous ruling classes, and anybody found still harboring such beliefs was liable to be arrested. The lamas in Buryatia and Kalmykia were charged not only with betraying the class struggle but also with being either “in service of Japanese militarism” or engaged in “fermenting pan-Mongolism.” The monasteries were systematically closed.

The worst was still to come. Following the 1934 assassination of Kirov, the amiable Leningrad political leader, Stalin unleashed the full fury of his terror. Within the next three years most of the remaining lamas in Buryatia were arrested and either imprisoned or shot. Dorjiev was arrested in 1937 and died the following year in a prison in Ulan Ude. At the outbreak of World War II, the Buddhist swastika was dutifully removed from the floor of the Leningrad temple and the building was turned into a radio-jamming station.

Following his arrest (together with that of his wife and two young children) in 1937, Bidiya Dandaron, the young Buryat tulku and student of aeronautical engineering, was transferred to a camp in Siberia. His wife was released but died a few months later from tuberculosis. Dandaron was tortured—the scars from a cavalry saber remained until his death—and settled down to what was to be the first of his twenty-two years of imprisonment.

Although Dandaron would later refer to his time in the prison camps as “nineteen years of Stalin’s drudgery,” his time there was not wasted. After all, the best surviving minds in Russia were locked up together in Siberia. Dandaron brought to the camps a combination of yogic intuition, which had been nurtured in him from the time of his birth, fluency in classical Mongolian and Tibetan, which he had studied with the monks of the local monasteries, and a sharp scientific intellect. Against the oppressive backdrop of imprisonment, he managed to sustain and deepen his practice of meditation, continue his Buddhist studies through discussion with other incarcerated lamas, and offer instruction to any who sought insight or solace through the Buddha’s teaching. For twenty years Buddhism in Russia hung on by the most tenuous of threads in, of all places, the Gulag Archipelago.

In 1944, Dandaron was released from prison to the relative comfort of internal exile and worked as a record keeper in a paper mill. But in 1947 he was again denounced, arrested, and sentenced to a further ten years in the camps. Now in his mid-thirties, he increasingly assumed the role of teacher and counselor, leading groups in Buddhist philosophy and meditation as well as writing articles and books. Finally, in 1955, he was released and rehabilitated in Buryatia, where he was appointed as a research officer at the Buryat Institute of Social Sciences in Ulan Ude, responsible for cataloguing the huge number of Tibetan and Mongolian texts that had been deposited there on the closure of the monasteries.

Two years later, the seemingly more liberal climate of Khrushchev’s Russia lured back home from thirty-eight years of exile the eminent Buddhologist George Nikolaievich Roerich. Roerich was renowned as one of the world’s leading experts in the field of Tibetan and Mongolian studies. On his return he was appointed as the first director of the Buddhist branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies in Moscow, and his arrival there stimulated a vigorous new wave of Buddhological research. In 1958, Dandaron met Roerich and the two men decided to collaborate. All of a sudden Buddhist texts started being translated again and articles appeared in scholarly journals discussing problems of Buddhist philosophy.

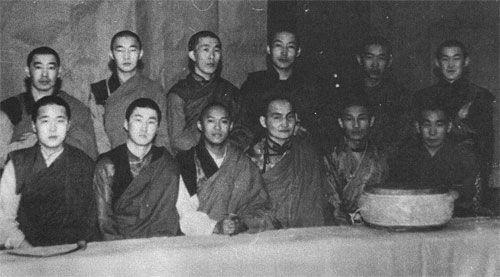

Unlike some westernized Buryat intellectuals, Dandaron was not interested merely in providing information about his native culture and religion; he was a practicing yogin and lama, concerned with passing on the Buddhist traditions of which he was one of the very few surviving practitioners. By 1965, a circle of disciples had gathered around him, including an increasing number of Europeans who would travel many days by train across the Soviet Union to Ulan Ude to spend time in his company. He attracted a diverse group of men and women, united by a common despair about the materialism of the Soviet system and a profound need to discover a spiritual dimension to their lives.

Dandaron was no romantic who rejected the contemporary world in order to dream of a long-lost, idealized past. According to his disciple Alexander Piatigorsky, he “worked on the interpretation of the main propositions of Buddhist philosophy so as to enrich and develop modern scientific thought. At the same time he worked on an interpretation of a number of basic propositions of modern philosophical and scientific thinking so as to give them meaning in the context and spirit of Buddhism.” Dandaron combined this intellectual enquiry with traditional Tibetan Buddhist meditation training and, in particular, Vajrayana practice, instructing his students in the sadhanas, or spiritual disciplines, of the Anuttara yoga tantras (“supreme yoga tantras”) and engaging with them, sometimes using forceful and eccentric methods, to shock them out of their habitual attitudes. He used to say that it was not they who were coming to him in Ulan Ude but Buddhism that was going West.

Yet the legacy of Stalinist intolerance still festered in the air. On September 19, 1972, Dandaron was arrested once again, this time accused of running an illegal Buddhist sect that practiced animal sacrifice and ritual sex, attempted to murder anyone who sought to leave, and had ties with international Zionism. Shortly afterward four of his European disciples in Buryatia as well as numerous Buddhist scholars throughout the Soviet Union were arrested and interrogated on grounds of being implicated in his “cult.” Although charges against the scholars were dropped, the four disciples were declared insane and dispatched to psychiatric hospitals. Many others of his circle, including relatives, were declared “morally unsuitable” and consequently lost their jobs. Dandaron’s writings were confiscated by the KGB and disappeared.

One might have expected such bizarre accusations to have rallied Dandaron’s fellow Buryats around him, to have raised him up as an innocent victim of KGB oppression against persecuted minorities. But although faceless officials in Moscow were doubtless at the root of this farce, they had no difficulty in persuading the local Buryats, even his colleagues at the institute, to denounce him and to testify against him. “They hated him,” recalls Piatigorsky, “precisely because he belonged to their spiritual tradition, which they themselves had repudiated. . . . Dandaron, as it were, served as the living reminder of their apostasy from their former culture.” The local paper, Buryaad Unen, commented: “If we look carefully at the members of Dandaron’s group we can see that they are all as bad as each other—questionable, suspicious individuals. They have no conscience, no honor, . . . no notion of fatherland, of family, they are true vagrants, capable of anything to get money. In reality they do not believe in Buddhism but are hiding their dark deeds behind religion.” Thus the KGB, anxious to stamp out a growing spiritual movement among Russian intellectuals, successfully manipulated local Buryat prejudices to achieve its ends.

In court, Dandaron was portrayed as a drunken profligate and speculator in Buddhist antiquities who cynically exploited the gullibilities of others in order to be worshiped by them. In the end, on December 25, 1972, he was found guilty on two counts: infringing the person and rights of a citizen under the guise of carrying out religious ceremonies, and financial opportunism. Sentenced to five years’ hard labor, he survived less than two years in a corrective labor camp on the shores of Lake Baikal. The official cause of his death on October 26, 1974, was given as pneumonia and a brain tumor. He was buried near the camp, and his relatives were not allowed to exhume the body.

Yet even as the aging Dandaron languished in a Siberian camp, another movement was underway that disseminated Buddhism in European Russia. This was the hugely effective samizdat (underground) publication of contemporary Buddhist writings, which were translated anonymously from English into Russian and circulated among a network of contacts in carbon and Xerox copies. These books began appearing in the late 1960s with the works of D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts on Zen, and those of W. Y. Evans-Wentz, Alexandra David-Neel, and Lama Anagarika Govinda on Tibetan Buddhism. By the late 70s interest and demand was such that only three to four months would elapse between publication of a Buddhist book in the West and its appearance in a Russian samizdat edition. One widely circulated title was Dandaron’s Thoughts of a Buddhist, a presentation of Tibetan lamrim (stages of the path) teachings in modern Russian, concluding with an introduction to the Vajrayana. Plans are now under way to publish the text in Ulan Ude.

Forbidden to travel to India or Japan to develop their interest in Buddhism, a few young Russians started making the long trek to Buryatia in hopes of finding lamas there. After the war, the authorities had allowed the establishment of two monasteries: Ivolginski near Ulan Ude and Aginski near Chita. A handful of lamas who had survived the camps were permitted to live and conduct ceremonies there. This allowed the Soviet Union to present showcase monasteries to the outside world as well as to send representatives to international Buddhist conferences. By the time the first curious Russians arrived in the mid-70s, they were received by a handful of old monks, who, despite their age, agreed to teach them. In this way, European Russians succeeded in establishing contact with living teachers from both the yogic and scholastic lines of their own indigenous Buddhist traditions in Buryatia.

In 1985, with glasnost and perestroika in the air, the trickle of Russians traveling to Buryatia to study Buddhism increased dramatically. Buddhist teachers from such diverse places as the United States, Korea, and India began to visit and teach in the Soviet Union, and in 1987 the Fourteenth Dalai Lama stopped off in Leningrad en route to Mongolia. Symbolically, the most significant recent event has been the return of Agvan Dorjiev’s temple in St. Petersburg to the Buddhist community in the city. In November 1989, Tenzin-Khetsun Samayev, a young Buryat lama recently ordained by the Dalai Lama in India, was appointed as abbot, and in January 1991 he settled in. A month later the statute of the Datsan Kuntsechoney (Dharma Place of Wisdom and Kindness, the name originally given by Dorjiev) was officially registered.

Except for the spire missing from the top, the temple looks much as it did at the time of Dorjiev. Although rather shabby, the boardinghouse where Ostov Budayev was arrested in 1937 still stands next door. No longer an elegant avenue with horse-drawn carriages, Primorski Prospekt now rumbles with the noise of trucks, buses, and cars. The view across the road, over the broad, still canal to the wooded park on Eliagin Island is largely unchanged from what Dorjiev and his monks would have seen.

On entering the building one is struck by fragments of its former grandeur: metalworked lotus leaves at the base of the dark red marble columns in the portico, carved wooden lintels around the doors, painted motifs high and inaccessible at the tops of pillars, stained-glass representations of the eight symbols of good fortune. Yet the overriding impression is one of disrepair and abandon. Crude scaffolding props up perilous ceilings. The bureaucratic gray and yellow paint slapped over the vivid Tibetan colors is blistered and peeling. The concrete stairwells are dank and cold. The main hall is bereft of either sculpted or painted images. Only on closer inspection does one find a color snapshot of the Gelugpa Assembly Tree on a makeshift altar. In addition to Abbot Samayev, eighteen young Buryat novices, their bright red robes the only signs of warmth and comfort, live in bare rooms on the upper stories. Although a poster on the wall proudly declares celebrations to mark 1991 as the 250th anniversary of Buddhism in Russia, like everyone else in St. Petersburg today the monks have barely enough to eat.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.