Tricycle is pleased to offer the Tricycle Talks podcast for free. If you would like to support this offering, please consider donating. Thank you!

In recent weeks, reporters, activists, and others have drawn parallels between the global pandemic and the climate crisis. It seems early to say, but we can sense that the two problems are more related than we think, as they are both challenges that we all must face together. Despite the fear, panic, and pain that rages on in our world, Joanna Macy says that she’s lucky to be alive in this moment—because when everything starts to unravel, we have an opportunity to rediscover our deep belonging with the Earth.

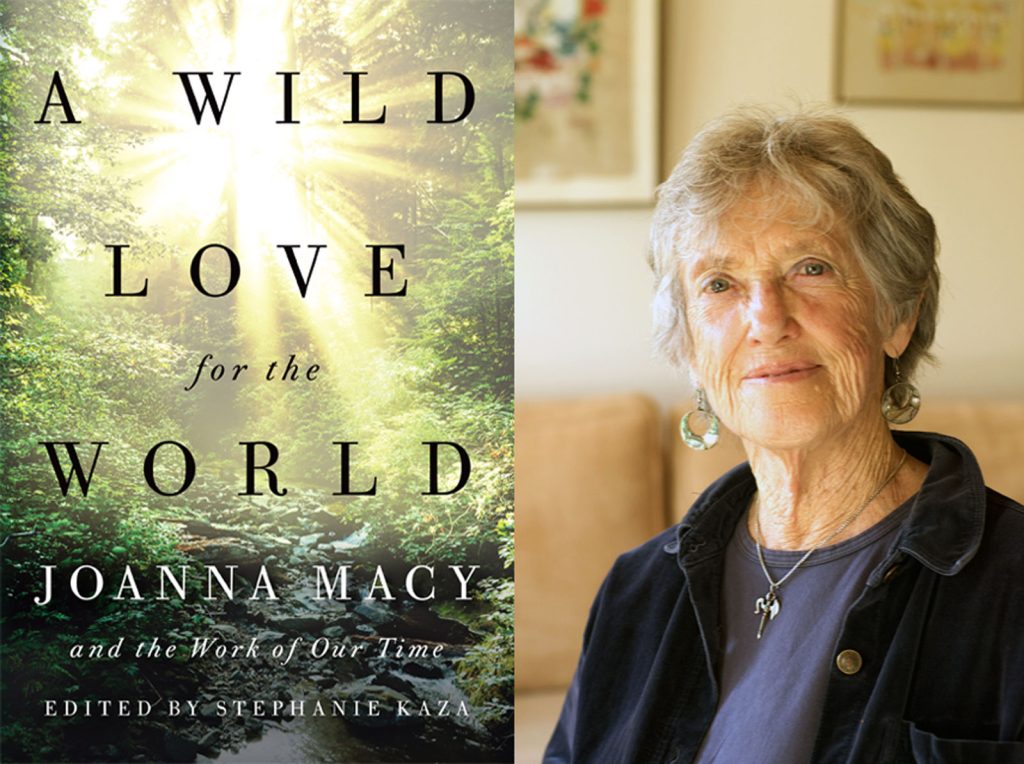

No voice has been as clear or as compelling as Joanna Macy’s in the intersection that lies between Buddhist practice and ecological movements. An environmental activist, author of eight books, and a scholar of Buddhism and deep ecology, Joanna has been on the front lines of the environmentalist movement for decades. In recent years, as our impact on the environment has become both more apparent and more perilous, activist groups like Extinction Rebellion and others have been turning to Joanna’s work as a source of inspiration. A new book, A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time, out today, celebrates her contributions with a selection of Joanna’s essays as well as writings by the many people she has inspired.

Tricycle’s Editor and Publisher James Shaheen talks to Joanna about how she believes we can move forward in a time of great despair—and how we can transform our despair into action.

Tricycle Talks is a podcast series featuring leading voices in the contemporary Buddhist world. You can listen to more Tricycle Talks on Spotify, iTunes, SoundCloud, Stitcher, and iHeartRadio.

Read transcript

James Shaheen: Hello, and welcome to Tricycle Talks. I’m James Shaheen, editor and publisher of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Environmentalists have long been nurtured and informed by Buddhist perspectives, but perhaps no voice has been as clear or as compelling as Joanna Macy’s. An environmental activist, author of eight books, and scholar of Buddhism and deep ecology, Joanna Macy has been on the front lines of the environmentalist movement for decades. And in recent years, our impact on the environment has become both more apparent and more perilous. New activists have been turning or returning to Joanna’s work as a source of strength and solace. Through her project, the Work That Reconnects, Joanna teaches people to face the grief and despair they feel about the ecological crisis and shows how we can transform these feelings into action. Her message is clear. In the face of climate disruption, our social, political, and economic systems are failing us, and moving forward means changing our relationship to the world without attachment to a certain hope or outcome. As scary as our world is, Joanna feels she’s lucky to be alive in this moment because, when everything starts to unravel, we have an opportunity to rediscover our deep belonging with the Earth. James Shaheen: Joanna Macy, thank you so much for joining us. Joanna Macy: It’s a delight to be in conversation with you, James, and I love your magazine. James Shaheen: Oh, thank you. Joanna Macy: To be here with Tricycle, it’s so fitting. James Shaheen: Yeah, it’s been a long time now. You know, we’ve seen a lot of energy surrounding climate movements this past year. Do you sense any difference in what’s happening now? Anything new happening? Joanna Macy: Yes, a great deal, partly because of the severity of the climate disruption, and because of what we see happening—whether it’s the burning of the Amazonian rainforest or the burning of the Arctic or the fires engulfing so much of central Congo and Indonesia—that sense of acceleration of what had been for many more or less abstract, we’re seeing it, and there’s alarm. And there’s also greater unrest, greater tides of refugees, and the wars that have pushed them out and the occupations are all climate related. Their symptoms are accelerated by the climate. And also the citizen movements such as XR, as they call Extinction Rebellion, that’s happening here too, and in a way, that’s exciting. James Shaheen: Yeah, I was going to ask you about Extinction Rebellion, and I was wondering how you felt about their efforts and their more disruptive efforts. Joanna Macy: Well, I’m moved by it, James, when I talk to people who’ve been involved in it. And a lot of people who I know through the Work That Reconnects that I’ve been doing find this a natural expression, the kind of response to challenge and the call to action that is generated very frequently by the teachings, writings, and participative workshops that I’ve been involved with over the last forty years. James Shaheen: You know, for decades, people have been talking about what they call the coming climate crisis, and you say now, and I think rightly so, that it’s here already. We’ve had inclement weather here that has caused floods. It’s very unusual for us to have a hurricane, as we did a few years back. You’re having fires in California. I mean, there’s evidence of it everywhere. When did that shift occur? I understand that this happened gradually, but is it your sense from your research and study over the years that it’s now cascading? In other words, it’s here. Is that correct? Joanna Macy: That’s right. I think different people have different moments when, as they say, the penny drops. It could be when your farm was flooded, the river took it over. There could be times when you just lost your last harvest. And for me, for example, when I realized that this was totally different was a year ago this month when the IPCC—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—report was in a different tone with different words than any of their communications before from this usually most moderate of scientific sources, and that shook us. And at the very same time, Bolsonaro was elected president in Brazil with a very open promise to the people that he would cash in on the Amazon, and that he was going to invite those companies in who wanted to make money off the Amazon. You know, that’s history now, but what a history. And it was at that point with these two things happening together that I thought that we cannot reduce our CO2 emissions—even begin to because we haven’t even begun to reduce them—without the Amazon. We can’t do it without the Amazonian rainforest. So that was when I got shook. But when was it for you? James Shaheen: When was it for me? I think Hurricane Sandy. I live in lower Manhattan, and we flooded, and it was so clear to me that this was something very different from what we’d experienced before. And it’s impossible to say based on one hurricane that things have changed, but the climate has noticeably changed in the last thirty-five to forty years I’ve lived here. So I think that flood brought it home. And the interesting thing is that often we’re not moved until we’re inconvenienced. That’s unfortunate but true. Joanna Macy: And we can see it with our eyes, can feel it with our bodies, yes. James Shaheen: I was sitting quietly at home and the storm hit, and it blew in one of my windows. So that was something that I never experienced before. But somebody in the office was talking also about infrastructure disruption and how people respond to that, and how will we respond when this happens more frequently? And it’s not just a question of a week’s inconvenience but rather a change in the very way we live. Joanna Macy: You know, James, the work that I was called to—I was going to be and prepared to be a professor at the university level teaching Buddhist thought and teachings. That’s what I was inspired to do. I came home from hanging out with the Tibetan refugees in India in the 1960s, and I decided to go back to school in my 40s, because I was totally caught by the teachings of the Buddha, that sophisticated psychology combined with such moral clarity and the freshness of it. I felt invigorated by it. To be invigorated by something that’s over two-and-a-half thousand years old! But then just at the point of my defending my dissertation and preparing to teach, my activism, which is always there, took a turn. And I realized—it was almost a physical realization, a bodily impact—that we were on the way to destroying our world, that we could destroy it, and the system, our political economy, was so set up that we would if we could. And that threw me into a dark night of the soul for over a year. And out of that came a work, so that I felt glad to be alive, that there’s still something we can do, and there’s a lot to be done. But back then, it wasn’t even climate change. Back then, it was the scientific and the moral challenge of the Club of Rome report, and also what you could see around you already of the industrial growth society, what it was doing in the clear cutting, what it was doing in the drift net fishing. And so climate was not a driving force. And for the people who came to me who wanted to find ways that they could even come to terms with it, where they could keep their balance in such a world and find ever deeper roots that could empower them and help them envision a morally rewarding and physically appealing, life-sustaining society, here spiritual teachings and political, economic, social action and the effects of it went absolutely hand in hand. Jame Shaheen: Right. You know, you said that we’re lucky to be alive in this harrowing moment. But, frankly, a lot of us are not feeling so lucky. You talked about a dark night of the soul and emerging very happy to be alive. Tell us why we should feel lucky to be alive in this moment. Joanna Macy: Because the dominant political economy of our time is destroying our world and is so organized, systemically organized, that it can’t stop it. It’s set for profits. It used to be for a while they would talk about the rewards of corporate activity being profits, social equity, and ecological balance, but those last two fell away soon enough so that these huge, huge, electronically financial . . . and the financial industry kicking in with that and shaped by it, so that it’s set with one variable: to maximize profits and shareholder dividends. So we have a terrifyingly powerful economy, and we see what it’s doing, and it cannot stop in time the release of methane and CO2. But what’s amazing now for us, why you can be glad, is that it is falling apart. It is encountering the limits itself, and some of them have to do with climate as well, of course. So what we’re seeing is, and what I’ve been very interested in, to say the least, is bodies of thought that are tracing how civilizations fall, that look at the dynamics of collapse, studies that have been done in Western Europe, as well as here. And that we’re here at a moment, and it could be the most dramatic, the most overwhelmingly transformative moment in human history. It’s going to affect everything. And I am totally convinced, and so are my colleagues in France who study climate change, so are my colleagues in the Extinction Rebellion: We can make our way through. We are not automatically captured by this dying machine of the industrial growth society. In my work, we call it the unraveling, the Great Unraveling. And the work is based on seeing three stories that are happening and knowing you can choose which story you want to get behind. James Shaheen: What are those three stories? Joanna Macy: One is “Business as Usual”—what you hear from the politicians, what you hear from the corporate controlled media, what you hear from the military. Those are the main voices saying everything will be OK if we can just get back to growing our economy, trying to pull us back into the American dream. But now fewer people can find it convincing. So that’s one story. The other is “The Great Unraveling,” that things are coming apart, and we can feel it in our lives, in our neighborhoods, in our country, in our national budget, in our wars, and in our mass extinction of our fellow creatures, all the creatures of our planet. So that unraveling is very hard to face, but people carry it in their psyches. They carry it in their liminal consciousness. This is what we sensed over forty years ago, and so the work began with helping people deal with their despair that they carried, even though they didn’t like to talk about it. This was forty years ago, so the work got going with helping people find out, to plumb the depths of their despair, and then see that what it was based on was not some pathology but based on caring, and that caring was based on a deep sense of participation, of interbeing, of belonging to our Earth, to each other. This was tremendously releasing. So all of these three stories, they’re all true, but you can choose every minute, every second of the day, what your response is going to be. James Shaheen: What is, then, what you refer to then as “the Great Turning”? Joanna Macy: So that’s the third story, and that is a choice making and a transition. It’s a name for a transition out of our current mess to a life sustaining culture. James Shaheen: One of the things I’m thinking about as we’re talking, we talk about this machine that seems to be on autopilot, that is forever focused on growth, and we don’t seem to be able to stop it, and it’s unraveling. At the same time, when it comes to choice, you ask people what they’re willing to give up, or how are they willing to live? Are we willing to give up our very way of life in order to save the planet, and is it going to be a question of simply having to because we have no choice? Joanna Macy: Well, James, I don’t recall ever asking people to give up, but that they have an opportunity to live in relationship with each other and with the living body of Earth. James Shaheen: You know, you said something at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in northern California. I watched the video. I wasn’t actually there; I’m sorry I couldn’t be there. But you talk about falling in love with what is, or falling in love with the world, even when it’s on fire, and there’s a kind of optimism there again. You say we’re lucky to be alive. But what does it mean to fall in love with a world that’s in the midst of this Great Unraveling? Joanna Macy: Well, you know, James, I don’t feel that I invented that. That phrase came to me when I was stuck. My whole body felt dead in a chaos of fear, revulsion, horror, when I saw those closing curtains and the burning rainforest. So that coming up my left side was this roar, and it was like, “You, be with what is. This is your world. You are made by this world. You are to be with this world. It feeds you. It breathes you, it instructs you. It holds your ancestors and the future ones. There’s not one part of you that does not come from this world.” And then to say, “I will be open to this pain and suffering without fleeing.” It’s no fun to run away from it. We’ve tried that. It doesn’t work. You’re half alive. Your eyes are closed. You can barely see. No, I want to go where I can be. I want to go where I belong. My world is hurting. I’m hurting, but I will. And from every faith tradition, there is the recognition that we sense that we are with and held by a greater reality. James Shaheen: I have a question. We talk a lot about despair. One of my colleagues asked you once, “What do we do with this despair?” And you’ve talked plenty about that in a very inspiring way. I also want to ask about fear because, when we hear something like the Great Unraveling, I think on some level people sense that something’s falling apart, and it’s always been that way, I suppose. But we think of the effects of climate change, the displacement of people, large numbers of people, mass migrations, scarce resources, collapsing infrastructure; that engenders a lot of fear. So yes, there’s despair, because people who actually are trying to be with it see what they’re up against, and they’re trying to do what you say, to be with what is. I don’t mean that in a passive way. You’ve been nothing if not active your whole life and engaged. But what about the fear people feel? Joanna Macy: You are so right. I am scared. And we are not afraid to be scared. I know that I sound odd, but of course we’re scared. Of course we are. Make friends with it. In our truth mandala, there’s the rock that we can take and let it speak. We let our fears speak. We have the stick for anger and let our anger speak. The rage is deep. We have the dead leaves piled there to hold and let our grief and sorrow speak. But making friends with your fear. I am convinced it doesn’t work to try to be fearless, but I use the term. I’m seen as fearless, but it’s only because I’m not afraid of the fear. James Shaheen: I think what I’m getting from what you’re saying is that fear of fear is worse than the fear itself. Joanna Macy: Yes. You know that my academic work was looking at the core teaching of the buddhadharma, which is the central doctrine of paticca-samuppada, or the dependent co-arising of all things. It’s a radical view of the interdependence of all phenomena. And I compared that with systems theory, which I was also fascinated by. And there’s a systems concept that is very helpful here, that at every stage of evolution the codes that operated the system up to then, you find they’re not working anymore. The system begins to come apart. It needs to grow. If it’s a lobster or a tortoise, the shell has to come off. The shell has to develop different textures or different open linkages. In other words, at every moment of physical or mental evolution in the nervous system, too, you have to let go of the old codes by which the system self-organized, and when that happens, it is a kind of dying. Things look impossible and terrifying. And it’s in that time that allows for new apprehensions of reality and new responses to begin, through trial and error or through choice. So that’s a positive disintegration: You come apart, but you come apart so that you can grow and reorganize a rounded, more evolved set of values, different kinds of understandings, more complex responses. Well, this has fascinated me from the beginning as what I was helping people do in the Work That Reconnects, to let go and look at the old responses, weep with them, storm with them, and then you hold them much more loosely then, so that you can start reorganizing. The whole system does that with a much more inclusive, more sophisticated set of responses and capacities, greater capacities at each systemic level. So I see us now, James, and this is what gives me a sense of tremendous awe and gratitude: I’m so lucky to be here. I have felt that from the beginning. If knowing this was coming to complex life forms on our planet and to humanity, oh, I wouldn’t want to miss that. I’m grateful every day because, as scary as it is, it’s giving us a chance to move beyond the dominant trigger responses that we’ve been socialized with so far. It’s much easier and doable when we’re together, when we work together with honesty, transparency, vulnerability, ready to try things out, and taking on some project that we can do that satisfies our need to be useful and relevant. Does that make any sense to you? James Shaheen: It does make sense. But when you talk like that and the vast implications of this change, I realize how self-defeating it is to have a particular or specific outcome in mind. It’s more like: Stay open to the wonder of this change, as devastating and horrifying as it is. Joanna Macy: Yes, you said it. That’s just it. By saying that, you recognize that if you have a blueprint, if you, James, or I, Joanna, have a scheme—“This is what puts us through, we’re going to have this kind of a government or that kind of an assembly,” or whatever—our ego gets attached to that, and we are less flexible. So if we stay with uncertainty, it’s a combination of gratitude to be here, a sense of adventure, and readiness to just be with what is and not try to force anything but bring in the values. Just last Sunday, you know, I was at Spirit Rock. Have you been to Spirit Rock? James Shaheen: I have, yes. Joanna Macy: It was kind of adventuresome because it was a day-long workshop, and our utility had turned out all the power in the whole county. There were no lights. James Shaheen: We’ve been reading about that. Joanna Macy: Yeah, and they said, but we’re going ahead with the workshop. It was the only thing happening Sunday. We had well over one hundred that had signed up and, by gum, most of them came and there was a sense of it’s happening, we’re in something together. And there was a sense of awakeness. And in that awakeness, there was such a feeling of attention, there was an alertness in the room, and a gladness, at least that’s what I found. Gladness to be alive. We used something that I’ve learned through the deep adaptation work. Have you heard of deep adaptation? James Shaheen: Are you talking about the four R’s? Joanna Macy: Yeah, well, this is a kind of thought movement that started a little over a year ago from a professor of sustainability in the UK when he suggested that the most adaptive thing that we could do in the pickle we’re in is deep adaptation, to recognize that we can’t stop the forces that are disintegrating, are unraveling. We can’t stop the unraveling, and that’s true with positive disintegration too. But what he suggested were four R’s to help us find our way through. And these four R’s were: Resilience. And by that he meant—and so did we when we played with it at Spirit Rock—resilience, what are the values and behaviors we want to keep as we go through this journey and so much is falling away? But what do we want to hold on to? So that was our first one, and people sat in groups and talked about what they want to keep, and then after five minutes they would share with the rest of the people there if they raised their hand, we’d have four or five people sharing. My alert meter was just off the charts. And then the next R is Relinquishment. What do we want to let go of as we move through this collapsing, toward a Great Turning, this Great Turning now that becomes the new culture, the life-sustaining culture that we can begin to put together through our actions and responses, and maybe continue putting together? There are a lot of things that we’ve been doing in our lives and in our ancestors’ lives. So relinquishment, but it’s a lot we want to let go of. So that was wonderful. Then the next was Restoration. What do we want to bring back from the past or from our ancestors or from other cultures that would help us now, that we would love to have? And then the last was Reconciliation. With whom do we at this point in our journey want to make peace? And then we added a fifth, and that was Remembering. What do we want to remember, you know, of just how to hem a dress, or how to make applesauce, or what songs do we want to remember, what poetry do we want to remember, what visions do we want to remember? When that was shared around the room, there were many ideas of what we want to remember. The last one was, oh, we want to remember to dance. And my co-leader, Wes Nisker, put some dance music on one little speaker that was from a pocket generator, so we danced. James Shaheen: That’s at Spirit Rock? Joanna Macy: Oh, we danced. James Shaheen: That’s nice. Maybe a sixth R could be Rilke. I know you have a real connection to Rilke. Joanna Macy: Oh, yes, yes. Well, James, this was the first poem of Rilke’s . . . On a snowy day in Munich when I was living there seventy years ago, I found this little book and it said Das Stunden-Buch, The Book of Hours, and I opened it to that very poem, “Ich Leben mein Leben in wachsenden Ringen.” I live my life in widening circles I’ve been circling around God, that primordial tower James Shaheen: Thank you. You know, I first came across Rilke when I was seventeen. I was in school, I was in high school in Cologne, and so that brings back when I was at the Gymnasium. So it’s interesting to hear that you were there in Munich when you were 20. That’s nice. I want to ask you something else. You are very fond of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche’s book In Love With the World, which is a nice title given your advice to us to fall in love with the world. But what you described this transition as was a bardo. Can you say something about that? Joanna Macy: Yes, it helped me see that we need all the help and metaphors we can get to keep us from being impossible during this time, or crabby or self-pitying. That’s the most boring thing of all is to pity ourselves. But anyway, Mingyur Rinpoche, even as a boy monk, learned a lot about the bardos, and so he saw that the four-year wilderness in his life that he created by secretly walking out of his room, his monastery, and disappearing into India, he saw that clearly as a kind of bardo. And I began to think about, oh, this time of climate destruction, this bleak landscape of the crumbling of a whole political economy, it’s a bardo. In the bardo, the first Buddha you see, because you enter from the east, is Akshobya. And Akshobhya Buddha is characterized by water. He rides an elephant, and his wisdom is like a mirror, like looking into a clear pond. It’s mirror wisdom—you dare to see what is there. It comes right back into what you were asking about. “Falling in love with” is being able to see the world as a mirror of you, of us. “Don’t look away,” the bardo reads. Don’t turn away. Face it, face it. It’s in the facing of it that you will be liberated and your powers be empowered to go where you need to go and do what you need to do for the arising of a regenerated society. James Shaheen: Joanna, that was really nice. Thank you. You know what, I did want to mention one more thing. In April, a book is coming out. It’s a collection of essays by over forty artists, writers, scientists, activists, and religious leaders, and they’re paying tribute to your influence on their work. So can you say something about that book? How did this come about? I think it’s to celebrate your 90th year. Joanna Macy: It was the brainchild of a wonderful woman who had a course with me, wow, over thirty years ago. James Shaheen: Just so our listeners know, you’re referring to Stephanie Kaza who is the editor of the book. Joanna Macy: Yes, and she had gotten to know the work, and she was then hired by the University of Vermont and became a nationally, widely known and respected director of the graduate school in environmental studies. But she followed me, and she was aware that her own work bore the imprint of our work together, and so when she retired a few years ago, she quickly published a couple of books that she had been dying for a few days of clarity away from work to bring out. And then she suggested this to me. James Shaheen: Nice. I understand it’s to celebrate your 90th year. Is that correct? Joanna Macy: Yeah, that’s right. So it’s going to come out in April while I’m still 90. James Shaheen: Oh, good. Listen. Do you mind? You’ve been very generous, and you’ve been hanging in there. A few members of the Tricycle staff asked me to ask you a few questions. Would you mind answering just two? I’ll pick the short ones. Joanna Macy: Oh, sure. James Shaheen: OK. One of them is: “How can we avoid thinking about the forces we are up against as evil? Where is the goodness in decades of destructive inaction? Joanna Macy: Well, first of all, that is the absolute quickest way to tear our world apart, to project that they’re evil. You know what I would like to do right now, I would like to answer that with the Shambhala prophecy. It’s been so helpful to me, and actually I am teaching it now at San Quentin State Prison, a whole series of teachings on how to be a Shambhala warrior. But it starts with the prophecy, and that prophecy is how I’d like to answer that question about evil. May I? James Shaheen: Yes, of course. Joanna Macy: OK, I bow to my teacher, Drugu Choegyal Rinpoche of the Tashi Jong community in the Kangra Valley of northwest India. There comes a time when all life on Earth is in danger. In this time, great powers have arisen, barbarian powers, and although they waste their wealth in preparations to annihilate each other, they have much in common, and among the things they have in common are weapons of unfathomable devastation and death, and technologies that destroy the world. In this time, just now, when the life of all beings hangs by the frailest of threads, the kingdom of Shambhala emerges. Now, you can’t go there, because it’s not a place. It lives in the hearts of the Shambhala warriors. You can’t tell a Shambhala warrior by looking at her or him, because they have no insignia, no uniforms. They have no barricades behind which to rest and regroup or from which to climb to threaten the enemy. They don’t even have any home turf. They must move across the terrain of the barbarian powers. But now the time has come when great courage is required of the Shambhala warriors, moral courage and physical courage, because they are going to go to where the weapons are made and deployed and dismantle them. And to dismantle weapons in every sense of the word, they are going to enter the corridors of power where the decisions and policies are made. And then he said, “Joanna, mark this: The Shambhala warriors know that these weapons can be dismantled because they are manomaya, made by our human mind, so they can be unmade by the human mind, because the dangers that face us are not brought about by evil extraterrestrial forces or by evil divinities. They spring from our daily actions, from our delusions, from our appetites, from our choices. They are made by the human mind, these dangers, so they can be unmade.” So he said, “Now is the time that the Shambhala warriors go into training.” “How do they train?” I asked. And he held up his hands the way the monks hold the ritual objects in the great lama dances of his people. And he said, “One is compassion and the other is insight into the radical interdependence of all phenomena. Now, you need the compassion because that’s what moves you out to do what you need to do. It boils down to not being afraid of this suffering, and when you’re not afraid of the suffering, then you can be there to affect the interactions that alter it.” But he said that compassion is very hot. “It’s so hot it can burn you out. So you need the other implement, the other tool, which is wisdom or insight. Then with that, you know that this is not a battle between the good guys and the bad guys, but that the line between good and evil goes through the landscape of every human heart, and that we are so interwoven in the fabric of existence or in the jeweled net of Indra, that even the smallest act with clear intention has repercussions through the web of life beyond your powers to comprehend or even see. But that seems a little abstract, doesn’t it? A little cool? And so you need the heat of the compassion to warm up the cool of the wisdom.” And when he said that, he said, “You need them both.” And then I remember how at Tashi Jong in the puja hall I could see the monks chanting with their hands moving and moving mudras, and they were dancing the dance of prajna, of the dorje and the jewel of the passion. Yeah. So that’s my answer to the question. James Shaheen: That was a very long, beautiful, and unexpected answer. So thank you, Joanna. I’ll ask another one that might sound a bit more prosaic by comparison. Joanna Macy: I won’t be so long next time. James Shaheen: Oh, that’s OK. I enjoyed that. Joanna Macy: But it’s a pretty good answer. James Shaheen: It’s a pretty good answer. Yeah, I wasn’t expecting that, so that’s wonderful. I’ll ask one more if you don’t mind. Do you mind? Joanna Macy: No. James Shaheen: OK, so this question reads: “Naomi Klein frames the climate issue in terms of ideology and identity. For many climate deniers, the steps we need to take would create a more communal society, one that is in opposition to their hyper-individualistic worldview. What do you think of this idea? How can we work skillfully with the people who feel that their identity is at stake?” Joanna Macy: Well, that’s so interesting. I think that it is true. It’s true in the sense that it is my conviction that this crisis is at heart a crisis of our understanding of who we are, and that it is the fruit—a cruel, cruel life-denying fruit—of the hyper-individualism of the last five centuries, with our economy and the consumer society and the competition that it requires to get ahead and make the money. The whole system is built up and the result of it dismembers our society. We are trained to get ahead, for number one, me, and to compete in every way I can. That has so misshapen our experiences and the life of us. And I see the fruit of it, too, in working in prisons. We think it’s the Department of Corrections, but we isolate, isolate, isolate. So I think that here is the chance in this system with its mass incarceration. And there’s mass incarceration in the high rises too. There’s incarceration in the corporations, isolation in so many government agencies and policies. And in so many jobs. I see this positive disintegration that is happening is opening for us a way to bring in values where we can befriend each other and discover each other and ourselves anew. Yes, come back together into a deep belonging that is intrinsic in our natural world, in our formation, there’s a yes. So I think this is a wonderful time to be alive. James Shaheen: You know, as I was listening to you, I had another question when you said positive disintegration. So when you say that, I thought of that, and there’s something inspiring in that phrase. At the same time, is it the wrong question to ask: Do you think we’re going to make it? Joanna Macy: Well, this is a good one to end on, because I think there again, we’re asked to be present in this moment. In the buddhadharma, there’s no word for hope, hope or loss of hope, because it takes us out of the present moment. The present moment, brief as it is, is our gift. It’s our choice point. It’s where we breathe; it’s where we love; it’s where we taste; it’s where we hear. Everything else removes us. To cultivate a friendliness with uncertainty, because that’s the point, that knife edge where all we know is the next step, or the next step, is a place of incredible freedom. Stay there. If people ask you, “Will we make it?,” you say, “Maybe.” Will we fail? Maybe. Maybe you can be a good friend too. James Shaheen: Well, thank you, Joanna. You know, I feel very, very lucky to have had this conversation, and we’re all so grateful for your work and your generosity in taking the time to speak with us today. Joanna Macy: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you so much. And my warmest greetings to the great staff in that great, great journal of Tricycle. James Shaheen: Thank you so much, Joanna, that’s great coming from you. Thank you. You’ve been listening to environmental activist and author Joanna Macy here on Tricycle Talks. And keep in mind, if you’d like to read more about Joanna Macy, a new book called A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time, edited by Stephanie Kaza, contains essays and commentaries by those she has inspired over the years. We’d love to hear your thoughts, so write us at feedback@tricycle.org. Tricycle Talks is produced by Paul Ruest at Argot Studios in New York City. I’m James Shaheen, editor and publisher of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Thank you for listening.

that reach out across the world.

I may not complete this last one

but I give myself to it.

I’ve been circling for thousands of years

and I still don’t know:

Am I a falcon, a storm, or a great song?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.