Tricycle is pleased to offer the Tricycle Talks podcast for free. If you would like to support this offering, please consider donating. Thank you!

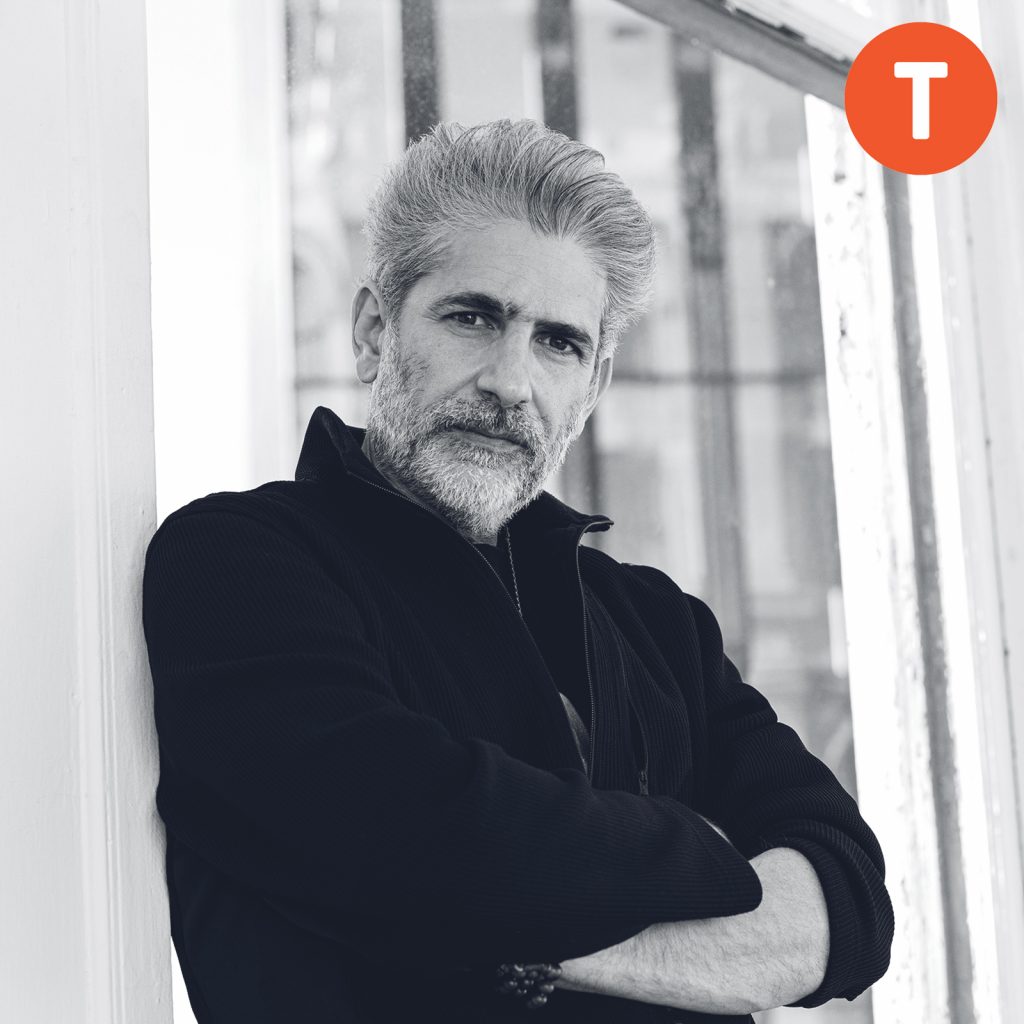

Michael Imperioli has a knack for playing mobsters and villains. Best known for his roles as Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos and Dominic Di Grasso on The White Lotus, the Emmy Award–winning actor has made a career out of exploring addiction and afflictive emotions on screen. Offscreen, though, Imperioli is a committed Buddhist practitioner. In 2008, he and his wife took refuge with Garchen Rinpoche, and during the pandemic, they began teaching online meditation classes together, exploring Tibetan Buddhist texts like The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva. Though his practice no doubt influences his creative work, Imperioli prefers to focus on the everyday ways that Buddhism has restructured his life. For him, Buddhism offers a way to liberate harmful emotions and cultivate patience and compassion on a day-to-day level.

In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sits down with Imperioli to talk about the dangers of the instrumentalization of Buddhist practice, what The White Lotus can teach us about craving and dissatisfaction, and whether he believes that liberation is possible in this lifetime.

Tricycle Talks is a podcast series featuring leading voices in the contemporary Buddhist world. You can listen to more Tricycle Talks on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, SoundCloud, Stitcher, and iHeartRadio.

♦

We’d love to hear your thoughts about our podcast. Write us at feedback@tricycle.org.

Read transcript

Michael Imperioli: The goal of Buddhism is not to make you a better actor. That’s like taking a Ferrari to go next door or something. But I do think meditation can definitely help your focus. So I think art demands a certain intensity of focus and concentration, be it performing on stage, be it sitting down, writing, acting a scene, you know, the more focused you are, the more in the moment you are in responding in the moment to what’s happening in your mind and what’s happening, interacting with others, the better. And I definitely think meditation can help that. James Shaheen: Hello, and welcome to Tricycle Talks. I’m James Shaheen, and you just heard actor Michael Imperioli. Michael is best known for playing Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos and Dominic Di Grasso on The White Lotus. Offscreen, though, he’s a committed Buddhist practitioner. I first met Michael back in 2009 shortly after he came to Buddhism, and it’s been a pleasure to watch how his practice has deepened over the years. In my conversation with Michael, we talk about how he first came to Buddhism, what The White Lotus has taught him about craving and dissatisfaction, the dangers of instrumentalization of Buddhist practice, and whether he believes that liberation is possible in this lifetime. So here’s my conversation with Michael Imperioli. James Shaheen: OK, I’m here with actor Michael Imperioli. Hi, Michael. It’s great to be with you. Michael Imperioli: Hi, James. Thanks for having me. James Shaheen: You’re best known as an actor, of course, most recently in White Lotus and famously in The Sopranos. For our listeners, they may not know that you’re also a devoted Buddhist practitioner. First, I’d just like to ask, did you have a religious upbringing of any kind? Michael Imperioli: Roman Catholic. My dad is still very devout. I didn’t go to Catholic school, but one day a week there was like a religious school after school at the church and we would go there so we could go through the sacraments like communion and then confirmation when I got a little older. To me it was more of a cultural thing than it was really a spiritual thing—for me, I mean. It’s different from my dad. James Shaheen: So how did you first come to Buddhism? Michael Imperioli: Well, when I was in my late teens, I started reading Jack Kerouac, who knew an awful lot about Buddhism. I mean, if you read his poems, they’re poems, but in The Scripture of the Golden Eternity, you really see the depth of knowledge he had about dharma and then reverted to Catholicism towards the end of his life, though. I was very curious about it through his writing, and I bought a copy of the Diamond Sutra at St. Mark’s Books, which used to be in the East Village on St. Mark’s Place. And I really couldn’t penetrate it. And it was pretty much the sutra, not a lot of commentary. I still have the copy of it, actually. I’ve managed to keep it all these years. I really could not make heads or tails out of it. So Buddhism kind of stayed in the back of my mind somewhere till much later, I guess 2007, my wife and I started going to Jewel Heart, which was in Tribeca at the time, and Gelek Rinpoche was teaching there. And that was the first time we went to a Buddhist teaching. And he was really our first teacher. James Shaheen: So how long did you stay with Jewel Heart? Did you stay with Gelek Rinpoche until he passed away? Michael Imperioli: Yeah, we went to teachings of his, and I lived in Detroit for a year and his other son is in Ann Arbor. So I would go to teachings on the weekend and sometimes would have lunch with him and spend time with him. He was a really great influence. And just a good human being and a really good teacher. And we were also going to teachings of a lot of other Tibetan Buddhist lamas, and didn’t wind up taking refuge till shortly after that with Garchen Rinpoche, after we had met him. James Shaheen: Yeah, you know, I remember Gelek Rinpoche’s place on St. John’s Lane, hidden away there, and it’s now the Village Zendo. They rented that space. Michael Imperioli: It was funny, because when my wife and I first walked in there, we realized we had both been in there in the ’80s, before we knew each other, when it was Madame Rosa’s, which was a very decadent late night nightclub. James Shaheen: I remember that. Yeah. You’ve come a long way. Michael Imperioli: No mud, no lotus, as they say, right? There’s a good example of it. James Shaheen: Absolutely. But I’ve heard you say that you came to Buddhism during the height of your success really. You say that something was missing. I’m curious because I always ask this question because I have to think about it sometimes myself. What was missing? Michael Imperioli: Maybe it’s not so much what was missing, but there was no kind of satisfaction necessarily in the success that came. You know, I spent my late teens and twenties really only pursuing acting, basically. I mean, I didn’t do anything else. I barely traveled. I was in New York. I did every job I could. Becoming a success really meant something to me, to be honest, not just working, I’ll be honest, you know, I really wanted a certain degree of success. I was driven towards that. And when that did come, both on a professional level, even a financial level, and I had at that time a family and kids and friends, many, many wonderful things that did bring some happiness. There still was like, you realize that that wasn’t an end unto itself, that whatever achievement that was. And I just felt Intuitively that it was on a spiritual level, there was a wisdom maybe that was lacking, you know. Just doing another successful TV show or winning an Academy Award or something if that were to happen that obviously that’s not the answer or the end to something like that. Although if you’re pursuing acting as your life’s kind of passion, you’d think that would be, but it’s not. So I started exploring a lot of different spiritual paths actually before Buddhism, not really committing to any reading books and going to a few meetings, seeing different people and going to a few centers. Like I would read stuff like Krishnamurti, and when I was reading the book, it made a lot of sense and it kind of touched me. Then the book would be over and I just felt, OK, now what? It wasn’t really a connection to him per se, to his teachings, like a direct connection to it, or a practice per se to implement into your daily life. And then when we kind of stumbled into Jewel Heart and Buddhism, I saw the potential for a path and a practice. James Shaheen: So, you know, you mentioned your ambition, your desire to succeed in your career as an actor, and I remember many years ago, almost fifteen years ago, you sat on a panel with Gelek Rinpoche and Philip Glass, and I remember Philip saying that the very qualities that made him a success professionally were the same that he applied to his practice: attention, focus, discipline, creativity, among others. Has that been the same for you? I understand ambition is a tricky word, but the skills that you developed. Michael Imperioli: No, I mean, ambition has a negative connotation in some ways, right? It can, but listen, to succeed at anything, let alone an art form or something, you need a lot of tenacity and perseverance and discipline and passion and creativity. A lot of those are positive qualities, you know, admirable qualities. So yes, I agree. I agree with Philip on that. Practicing Buddhism takes a lot of discipline. And it takes a lot of perseverance, and commitment, and creativity in a lot of ways, and open mindedness, and honesty. That makes a lot of sense. I’m glad you brought that up. James Shaheen: You know, I met you after that panel that you were on with Philip and Gelek so many years ago, and I interviewed you in 2009, and the interview was pretty short. I’ve been listening to you on other podcasts, and it’s pretty amazing nearly fifteen years later to hear you talk about your practice with such commitment and depth now. So I was just thinking it helps me to see change in others that I often miss in myself. Do you ever feel that way? Because sometimes I don’t see the practice working. I’m not aware of it so much. I do it and I’m not so aware of it. And then looking back at that interview from 2009, you were a few years in, I believe. Michael Imperioli: Barely. James Shaheen: Yeah. And listening to you now, it’s like a world of difference. You know, that didn’t have to happen, but it happened. I guess you were karmically inclined, as they say, but do you ever see it in others when you don’t see it in yourself? Michael Imperioli: Yeah. Well, especially my wife, you know, because we’re both, we got into it together. We practice together. We talk about it a lot. We go to teachings together and it’s a big part of our lives and I see it in her. She’s a very committed—she would hate me saying this—devout Buddhist and is very knowledgeable, much more than I am. God, would she be so angry that I’m saying this, but she reads countless Buddhist texts. And when I say change, I see it in simple ways about, like, when somebody annoys you, you have an awareness that somebody’s annoying you. When you behave in a way that you really shouldn’t have or felt was letting the afflictive emotion of anger or something get the best of you, seeing that and realizing, either making amends and realizing that’s not what you want to do and not doing it the next time it happens, or finding a way. In those very simple ways, I really see the practice. I mean, I see the discipline she has and the commitment to it. That’s very clear. But in those little ways, those day-to-day ways, I see it. And it’s very inspiring to me to see the changes. James Shaheen: And so what sort of changes do you see in yourself, in your own life, in your own day-to-day? Michael Imperioli: You know, I find that more positive people kind of come into my life. Kinder people, generous people, compassionate people. I found that to be true. And that’s amazing. Ultimately, the practice is, right, bringing awareness to your existence, right, to your minute to minute, second by second, day to day life, bringing some awareness of, OK, what am I doing in this moment, what am I thinking? I went for most of my life kind of justifying my emotions, my reactions: “Well, I did this because they did this and that’s logical. She jumped in front of me or took too long in the line in front of me at the coffee shop, and now I’m angry.” We can justify, and that’s fine, those emotions all the time, but you’ll be stuck there. You know, those things don’t go away. But yeah, somehow I found more positive people coming into my life. James Shaheen: You know, I wonder, you mentioned that more compassionate and generous people come into your life. Do you think it’s also that you’re more aware of their compassion and generosity? That you’re more likely to see it? Michael Imperioli: No, I know it. James Shaheen: Just that that’s what you’re putting out and that’s what you’re receiving back. Michael Imperioli: I don’t know if that’s what I’m putting out, but maybe that’s what I’m seeking out. And by generous, I don’t mean financially. I mean, generosity of spirit and time. James Shaheen: I’m thinking in terms of dana, the Buddhist virtue of generosity. Michael Imperioli: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, of course. James Shaheen: Yeah, so often I think about Buddhist practice and becoming a kinder, more compassionate person. I mean, I don’t think that’s a modest goal. I don’t think becoming a better person, a better husband, a better family member and so forth, I don’t think those are modest goals. That’s the bare bones of life. You know, I mean, you can have somebody practicing forever and then snap waiting in line, yelling at the cashier or something like that. So I don’t think that’s a modest goal, but. You know, more recently, I’m, this has been on my mind, and so I’ll ask you. Anne Klein, she’s a scholar and a Dzogchen practitioner and herself a Lama. She said she was recently challenged by her Dzogchen teacher when he asked her, do you have confidence that you can achieve liberation in this lifetime? Do you ever go there or does it seem too lofty? Personally, I’m a little bit shy about going there, although my teachers do. So here we’ve got this big. Big idea, you know, and I’m nowhere close to it. I’m still focused on not snapping at my partner or the people I work with. And I consider it a victory when I have the intelligence and poise to make a decision not to be that way. And yet, sometimes I go back to Anne Klein’s teacher’s question, do I believe I can be free? Does that ever come up for you? Michael Imperioli: I agree with you, by the way, that that’s not a modest aspiration, right? Working with those afflictive emotions, becoming aware of them. I think liberation is possible in this lifetime, but it takes an awful amount of commitment. I’m confident that it’s possible. I’m not confident that I’m going to get there, but I don’t really think about it that much. You know, it’s like, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche said something, it’s in that documentary, I think, Crazy Wisdom, where he asked his sangha at one point, “You become enlightened. Then what?” He kind of likens it to like you being present at your own funeral. The idea of you with this ego mind becoming enlightened, you know, they’re kind of conflicting things because enlightenment’s the opposite of that. So he’s almost saying you can’t really have yourself and your ego and be enlightened. He’s basically saying it’s not this better version of you. It’s not Clark Kent becoming Superman. It’s something else. One of the mahasiddhas I think said something like, “I’m not impressed with people who can perform miraculous deeds like drawing water out of the wall or turning the ceiling into the floor, something like that, but liberate one negative emotion, and that’s a miraculous deed.” James Shaheen: I think it was Maezumi Roshi who said, “What are you so concerned about enlightenment for? What if you don’t like it?” Michael Imperioli: That’s great. James Shaheen: I always keep that in mind because on the other hand, sometimes I dismiss it too categorically. And I sometimes want to remember the possibility of being free is there, but I don’t dare hold forth on it or assume that this is going to happen. So on the note of negative emotions, you play Dominic Di Grasso on the White Lotus, and he seems like a case study in dissatisfaction, addiction, regret. Dominic can’t prevent the mistakes he has to make, although he pays for them in cash, and that’s both funny and at the same time, somewhat poignant. And it feels like fate, you know, phenomena just sort of unfolding. And yet practice is an opportunity to intervene. Most people won’t come to the practice. And I know you’re conversant with The 37 practices of the Bodhisattva. How do you think of that in terms of the bodhisattva vow? Michael Imperioli: You know, the bodhisattva vow is a really big commitment. It really is. James Shaheen: Kind of like enlightenment, you know? Michael Imperioli: Yeah, but it’s like you’re committing to, you know, because maybe when you first hear about Buddhism, you kind of think, oh, there’s a way to reach some heaven, basically, nirvana or something where all the suffering is gone or something. And then you take a bodhisattva vow and you realize, well, whatever that is, you’re not going to get there until everybody else gets there to some degree, and you’re hanging out for everyone else. But I think what the White Lotus really shows is those habitual tendencies that become so ingrained, both through your own, I guess, karmic imprints from if you believe in past lives, or just genetic in your DNA, or the learned behaviors that you saw in your younger years, you saw your parents or your family behaving in certain ways, or the culture you were in. And that those things can really stay with a person and stay in a family unless something kind of cataclysmic or some kind of light bulb goes off, or both, maybe at the same time. I think the White Lotus, why it’s interesting to me, it’s like, here you have very, very rich people in the most opulent, luxurious, god realms surroundings. And they’re all miserable, pretty much. James Shaheen: You know, an Italian friend of mine told me that that place is flooded with tourism right now. Michael Imperioli: Oh, it is. It’s booked for years in advance. You know, because those things, although when you don’t have those things, you think this would really make me happy if I could live like this, if I could. travel first class and stay in the best hotels. And there you have a story of these people who actually do that and are not really very happy. There’s momentary happiness and there’s fleeting pleasures, but yet there’s some dissatisfaction that’s just not being satisfied. James Shaheen: Right. There’s an interesting experiment I did when I was much, much younger, I found this apartment in New York, which was no mean feat at the time. And I really loved it. I had a view of the Hudson river and I was thrilled and I was excited because it even had a window in the bathroom, which in New York isn’t guaranteed by any means. And I remember thinking, I wonder how long before I take this for granted. I wasn’t yet a Buddhist, I didn’t have a practice. But it occurred to me, we fall for it every time. We think just this will make me happy. And in White Lotus, it’s really clear that’s at play. And what I said to myself is, I fall for it every time. Michael Imperioli: How long did it take before you took it for granted? James Shaheen: Oh, I think it must’ve been about six weeks. And all of a sudden I was in a mood again. You know, I thought, I don’t care about that window. I don’t care about the Hudson River. I got lucky to get this place, but I’m going to move. I stayed there for several years, but it’s like that. But when I see the character you played, it’s interesting because it’d be easy for me to hate him if I didn’t also identify with him. He wants his wife back, and yet he’s in the throes of this addiction and he can’t help himself and he can’t help his son. And it was for me such an accurate description of the samsara that we all live in. And again, I thought practice can interrupt that. It’s a possibility anyway. Michael Imperioli: It is a possibility, but it’s even with practice, those ingrained behaviors, especially addiction, they’re very hard. Pema Chödrön talks a lot about how the path, a lot of it is one step forward, two steps back. And then maybe you go one step forward and it’s only one step back and you should rejoice in the fact that today it was only one step back. Like that’s progress.Especially things like addiction, like sex addiction and food addiction are very different than drug addiction or alcohol because you have to eat. You just have to find healthy ways to eat in ways that are not going to make you sick or make you die or whatever. And sex as well. I mean, most people are not going to become celibate. You want to integrate it into your life as a healthy element. And those things are tricky because they’re not just about abstaining really. Those things are a little tricky. And there’s a lot of gray area around them. I think practice can help because to really practice Buddhism in my point of view, it really requires real honesty with yourself. You really have to kind of have a bold, honest view of your own mind and your shtick and your things in many ways that people uncover through psychotherapy with psychologists and psychiatrists and things like that, but in a bit of a different way, in a very day-to-day way, sometimes a mundane way, but you really have to make a commitment to being honest with yourself. And that’s sometimes very hard. James Shaheen: Yeah, you know, I found sangha and of course a teacher are essential in being honest with myself. You know how a teacher can say something that cuts right through your fabrications. That’s always an amazing thing. I remember once I was harping on something and my teacher looked at me and said, “Why do you care so much?” And all of a sudden it shattered. You know, I was sitting there seeing myself, this repetitive person harping on the same thing. And I had to really consider, Why do I care so much? But the practice is interesting in relationship with others and with the teacher, without which I don’t think I’d have made any headway at all. Michael Imperioli: Oh, same for me. I don’t think it really exists outside of that. James Shaheen: No, it doesn’t. It doesn’t. And also breaking habits, whether it’s an addiction or anything else. the support of others I found essential. But just one more question about the character you played, Dom, because he’s a very nuanced character actually, he’s not just a shit, he’s also somebody who wants his family. Did it give you any insight into the nature of craving or dissatisfaction? Michael Imperioli: You know, I was definitely familiar with that kind of pursuit of pleasure. And then the feeling of regret after when there’s something that you know is bad for you or that you know is wrong, but you’re kind of drawn to it, and then it’s like a hangover he’s experiencing that when he wakes up in the morning and then there’s two girls in the room and he probably went to bed smash drunk and was feeling kind of good and then woke up and it’s just like, “Oh my God, what did I do? And what did we do?” And, you know, that thing that was so pleasurable the night before that seemed so pleasurable now has turned to shit. James Shaheen: Despair. Michael Imperioli: Despair. You know, because the nature, as they say in the dharma, the nature of these things is not inherently real. I like pizza, but if I ate two pizza pies, I’d be hating life. You know what I mean? So the pizza is not, you can’t say it’s inherently pleasurable because it could also cause a lot of pain. It’s interdependence, right? Our relationships to it and how we relate to everything. James Shaheen: Of course, until tomorrow, when you want pizza again, that’s the cycle. And then maybe you’ll eat three because it’s progressive desire. Michael Imperioli: Exactly. James Shaheen: So Michael, in addition to being an actor, you’re also a musician. Can you tell us a bit about your band Zopa? Michael Imperioli: Zopa’s an indie rock trio that was formed in 2006, and then we took a hiatus when I moved in 2013 for about seven, eight years. And then two and a half years ago, we started playing again. I play guitar and sing some of the songs, and it’s a very collaborative group. We’re influenced by some of the New York bands from the ’70s like Television and The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed and Patti Smith and people like that and then also a lot of ’80s post punk like The Smiths and Echo and the Bunnymen and ’90s bands like Nirvana and the Smashing Pumpkins and My Bloody Valentine and stuff like that. James Shaheen: Some of your songs include traditional Tibetan chants. So how do you bring together these chants with this sort of post-punk indie rock? Michael Imperioli: There had been over the years some Buddhist themes in the songs. And then we have a new song and the verses, there’s two verse sections and they’re the seven-line prayer of Guru Rinpoche in Tibetan. You know, it just made sense. There’s something cool about playing it live or people listening to it. Those mantras and prayers have a certain frequency and resonance that might touch people in some positive ways. James Shaheen: Yeah, that’s a very direct example of how your practice finds its way into your work, but more generally, how does practice influence or shape, if it does, your artistic endeavors, whether acting or playing music? Michael Imperioli: I think it, you know, meditation can, and I don’t really like talking about this because I really only know meditation through my practice, through Buddhism. I don’t really know meditation as a thing that’s separate from Buddhism. And the goal of Buddhism is not to make you a better actor. That’s like taking a Ferrari to go next door or something, you know what I mean? James Shaheen: People do it. Michael Imperioli: People do it. But I do think meditation can definitely help your focus. I think art demands a certain intensity of focus and concentration, be it performing on stage, as an actor, as a musician, be it sitting down, writing, acting a scene, you know, the more focused you are in the moment, the more in the moment you are in responding in the moment to what’s happening in your mind and what’s happening, interacting with others, the better. And I definitely think meditation can help that. James Shaheen: So in other words, it kind of sounds like to me it’s an ancillary and unasked for benefit, but you point out something very interesting and important, I think, the instrumentalization of our practice in order to get something. And any of us can fall into that, but I likewise see my meditation practice, I cannot see it outside of my practice, and the wanting, the wanting, the wanting that tugs at me at the back of my mind is something I become aware of, not good or bad, I’m just aware of it. So I really appreciate that. And I like the Ferrari analogy. Michael Imperioli: Yeah, because it’s like that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche thing saying it’s kind of like being present at your own funeral. You’re not doing this. These teachings and a teacher and the fact that this tradition, which goes back 2,500 years or whatever is still in the world, that there’s still a lineage and a connection to that wisdom and those teachings, it’s so unbelievably precious that to kind of, like you said, instrumentalize it for some worldly purpose really is kind of counter to it. James Shaheen: Right. Michael Imperioli: You know, Listen, if you’re really making a commitment to practice, at some point there’ll be shifts in everything, right? In the way you interact with the world and the way you perceive the world. Maybe. Little ones. James Shaheen: Yes, I don’t know if you ever read Huckleberry Finn, but I was a huge fan when I was a kid and he does get to show up at his own funeral. They think he’s dead and they have a funeral and they say all of the typically hypocritical things. Michael Imperioli: That was really great. I read about a father who did that, who faked his own death and had his funeral and then showed up at the funeral a couple of months ago, I think in America. James Shaheen: You know, it’s funny, there was a guy in the West Village who was thought to have died and it was a rumor, but a group of people went out to the pier to sort of memorialize him. And I said, “Well, what’s the source of this?” And the source was somebody who was marginal, but they had a funeral for him. And one day he showed up and everybody disliked him again after they said all these nice things. Michael Imperioli: All these really nice things. James Shaheen: So the name of your band is also your dharma name, Zopa. So when did you receive the name? Michael Imperioli: Well, the original name of the band was La Dolce Vita after the Fellini movie. But I never quite really liked that name. And then when we took that hiatus or right before we took that hiatus, we decided to change the name, which I think was good. When I took refuge with Garchen Rinpoche. I got the name Konchok Zopa Sonam. So Zopa is patience in Tibetan. And the day I took refuge, he said, “Patience is the key to your practice because when you lose your patience, you lose your love.” That’s what he said to me. And at the time, I was still very new to Buddhism. You know, I took that as a very Hallmark card kind of pithy nugget, you know what I mean? Like, oh, yeah, of course, you lose your patience, you lose your love. James Shaheen: Kind of like lovingkindness. The first time I heard lovingkindness, I had a similar reaction. Michael Imperioli: Yeah, like, of course, that makes sense, but I didn’t really take it into heart, really. And years later, I forget what happened, but I was like, “OK, the day you took refuge with him, he said this to you. So maybe you should give it a little bit more importance than you ever had. Maybe you should really look into that, about patience being the key to your practice. And since I had that thought about it, I started to just take it more seriously, to really focus on that as much as I can, or as much as my awareness allows me to. Again, Trungpa Rinpoche said something very interesting about patience. He said if you’re a dharma practitioner, patience is an obligation. It’s not just something you do out of, because you want to be kind or something like that. If you’re a committed dharma practitioner, patience is an obligation. Not only that, but it’s always an opportunity to practice. When you feel yourself becoming impatient, if you can become aware and choose to bring some patience into the situation, these little annoyances become opportunities for practice. James Shaheen: Does patience find its way into your work and your process? Michael Imperioli: Being on a set can be long hours, a movie set, a TV set, 14-hour days, and sometimes it’s very chaotic, depending on who’s running the set. Depending on that person’s temperament and ability, you know, a set can be tumultuous and chaotic, or it can be kind of efficient and, and kind of calm. And as an actor, sometimes you’re going to some difficult places emotionally. You need to find a lot of anger. You need to find a lot of sorrow. And you need to have some concentration and all this chaos is going around. And it’s very easy to have done that many times, but practice definitely can make the experience of being on a set and working on a set all day a lot more pleasurable in a way and easier. I don’t mean easier in making the work easier, but just if you realize it’s going to take time, people are doing their best and bring some patience to it, it can really help. James Shaheen: I think about your playing impatient characters, so I wonder what role patience plays in playing impatient characters. And I think of something Mingyur Rinpoche instructed his students to do, and one of them was feel sad without being sad. And that kind of made me think of acting there. So be impatient without being impatient. So you’re playing this character. Are you really impatient or are you patiently playing out impatience? Michael Imperioli: Well, you know, you understand being impatient so then you can play it in the situation. As you understand, it’s when your awareness shifts from something wider to something really, really narrow. And it just becomes about that grasping thing about whatever desire it is to be satisfied, right? I want that person to stop paying in pennies because it’s taking 20 minutes and I want to buy my soda and get out of here. James Shaheen: You mean when they take out the little purse and start counting out the pennies? Michael Imperioli: Yeah. That’s a great opportunity to practice patience, right? Because in your justification, you could say, “Well, this person should know, doesn’t this person care that there’s five people waiting?” You know what I mean? James Shaheen: “Don’t they know I’m here and I need to go?” Michael Imperioli: Don’t they know I’m here? Of course. So there’s lots of good opportunities for practice and to see your own aggression. And I don’t mean aggression necessarily in a violent way, but sometimes ambition can be aggressive. Sometimes, like you said, being in line in the store, there’s an aggressive quality to that. Why is that person taking 20 minutes buying that stupid thing and asking all those questions? I keep going back to Trungpa. There’s a scene in that movie, Crazy Wisdom, I guess it’s early ’70s, maybe late ’60s, because it’s around the Vietnam War, maybe right after. And someone asked him about aggression in society. And he said, “I want to talk about the aggression in this room.” James Shaheen: Right, and get to know it really well. You know, we recently had Meredith Monk on the show, and she said that a lot of our artistic practice is waiting, back to patience, and trying to get out of the way. Does this resonate with you and how you think about the creative process? Michael Imperioli: Yeah, well, especially on a movie set, you spend most of the time waiting. But even more, like if you’re writing. So when I’m writing, say I’m on a project that I’m writing and it’s going to take a few months or something like that, and you set up a schedule: I’m going to write Monday through Friday from 10 to 3. Chances are you’re not going to be literally writing fingers on the keyboard for five hours. And there might be a big chunk of that time where nothing’s happening, and you’re not really waiting for inspiration because you can’t wait for inspiration because you’ll probably wait forever. But you have to trust that there’s some kind of other process going on subconsciously and that the mind knows that those hours that you’re there, there is some kind of alignment that you’re in tune with. the story, the character, somehow, even if you’re not actively writing about or actively imagining it, somehow the consciousness knows that that period of time is related to that. You have to trust that. There’s a lot of waiting involved in that. Is she a Buddhist? I didn’t know that. James Shaheen: Yes, she is. She is a Buddhist. I believe Trungpa was her teacher many years ago, and she continues her practice now. She is very fond of Pema Chodron. And we spoke with her over the years. She’s been in the magazine several times. Michael Imperioli: Oh, that’s cool. James Shaheen: Yeah, she is. But, you know, during the pandemic, you started teaching meditation. So how did you make the decision to start teaching? And how has teaching changed your own practice? Earlier, I asked you about the bodhisattva vow and sometimes the impossibility of reaching people who simply aren’t turning toward the dharma, but here you are with people who are turning toward the dharma. That must be a joy. Michael Imperioli: Yeah, it was interesting. I got onto Instagram right before the pandemic, like months before. And, you know, I would just really post other artists that inspire me and authors and musicians and filmmakers, actors, and I would post some Buddhist stuff. There’s a few great Instagram pages that I constantly send on my stories. And a lot of people started writing to me asking me how to meditate because they knew I was a Buddhist, because during the pandemic, people were very, they had a lot of time on their hands, they had a lot of anxiety and fear, and they felt that meditation could help. So I would write back to people, very simple meditation instructions, people I didn’t know, you know, just fans writing in, and I would direct message people. It started happening a lot. So I was like, maybe I should just make a video and then people could just watch it rather than me typing in these things all the time. And I tried to do it on Instagram Live and it was a real disaster. And then somebody wrote to me and said, “Do you need tech help?” He said, “I work for Second City in Chicago and we do these Zoom webinars. And maybe that’s what you should do.” And then I wrote to my teacher and explained I’m on Instagram and a lot of people are asking me for meditation instruction. And I said, “Should I do this as a class?” At the time, it was completely secular. Nothing about Buddhism, just calm abiding meditation. He said, “Yeah, that’s a great idea. You should do it.” And I found this, he was very young, I think he was only 25 at the time, Nick Solideo, who wasn’t a Buddhist or anything, but he was a fan of mine. He said, “I could help you do this Zoom webinar. You can promote it on Instagram, but then people have to sign up. It takes a little more effort than just tuning into Instagram. They sign up and you do it.” And I said OK. And I started paying him to do this and we started in the pandemic. And a few weeks later he wrote back, he said to me, “I don’t want to be paid for this because he saw people were writing in that it was helping them,” and he said, “I don’t want to be paid for this.” And I said, “Well, that’s really sweet and cool.” So we started doing it and I’d have like a question and answer thing. A lot of the questions were about Buddhism, particularly karma. Karma was a big thing they were asking about. And some other things about Buddhism. And I wrote to my teacher and I said, “You know, a lot of the students are asking about Buddhism. What do I do?” And he said, “If you talk about it, just keep the focus on the mind.” And he said, “Remember, Buddha is not the name of a man, it’s the name of mind.” So I’m not a dharma teacher by any means. It’s more like I’m a student maybe that’s been around longer. And my wife does it with me now. We really only try to, we’ll read some excerpts of sutras or other teachers and commentaries and stuff. but really only try to talk about my own practice and how I’ve implemented the practice in my life. I’m not a dharma teacher by any and in fact most of the time in pretty much every class I encourage people if they are interested in this to find a teacher from an authentic lineage. I offer some suggestions. But I also just say if you really are, you don’t have to, you could certainly meditate and not be a Buddhist and not study dharma, not take vows, refuge vows or anything. But if it does call to you, this tradition is alive and available, and really to find a teacher is critical if you want to follow that. James Shaheen: Right. You know, it doesn’t surprise me that this began during the pandemic. We began airing live teachings during the pandemic and thousands came when we put Pema Chödrön up. 30,000 people watched. So it was pretty amazing. And tough as that was, it was an opportunity to do what we do. And it sounds like you did something very similar. Michael Imperioli: And the class is still going on now, three years later. And a bunch of the people have become Buddhists. And some even have taken refuge with Garchen Rinpoche and other lamas too, which is pretty cool. James Shaheen: What is the URL that our listeners can go to if they want to listen? Michael Imperioli: They’re all archived on YouTube as well. But the website, if you follow me on Instagram, I promote the class and put up the sign-in link the day before. So on Instagram, it’s realmichaelimperioli. Speaking about 30, 000 people, we all talk about technology and how we’re afraid of it and how the negative, that’s one of the amazing things about technology is 30,000 people, many of whom might never had heard the words of Pema Chödrön or attended a Buddhist teaching or something like that and because of technology there they are, and that’s a good thing, right? James Shaheen: Yeah, likewise we use social media to disseminate the teachings. We do the best we can in a pretty troubled world, I would say. But one last question. You’re a public figure, people notice you walking around, they know who you are and I think of the eight worldly winds two of which are praise and blame. How do you navigate the praise and blame? Because if you’re in the public eye, it’s got to even be more intensely present. Michael Imperioli: You know, for a lot of people seeing someone famous or someone from a movie or TV show, especially a movie TV show that they liked a lot, for them, it’s a special kind of moment that makes them kind of happy, at least for that two minutes or something like that. So I try to focus on that. It’s like I’m not making them happy. It’s like their perception of the situation is what’s doing it. And if you can walk around town and people get happy because they see you, that’s very positive, right? And I also try to say to remember that it’s their projection of whatever they’re responding to. It’s not my innate qualities per se. They’re seeing a lot of different things. They’re seeing a character. They’re seeing an idea of an actor. They’re seeing there’s a lot wrapped up in life. So I try to stick to the positive qualities of that. James Shaheen: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure. Thanks so much for taking the time. I appreciate it. It’s been fifteen years. But it’s great to see you again. Michael Imperioli: You know, that first time we met, I’ll never forget that one simple thing that Gelek Rinpoche said. You know, because people were talking about creativity, they were talking about lots of different things, and Gelek said, if you’re not becoming a kinder, nicer person, all of this is just blah, blah, blah at the end of the day. James Shaheen: Well, that’s a great way to end. Thank you, Michael. It’s been a pleasure. Michael Imperioli: Thank you. See you. James Shaheen: You’ve been listening to Tricycle Talks with Michael Imperioli. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast, so write us at feedback@tricycle.org to let us know what you think. If you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. To keep up with the show, you can follow Tricycle Talks wherever you listen to podcasts. Tricycle Talks is produced by Sarah Fleming and The Podglomerate. I’m James Shaheen, editor-in-chief of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Thanks for listening!

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.