Tricycle is pleased to offer the Tricycle Talks podcast for free. If you would like to support this offering, please consider donating. Thank you!

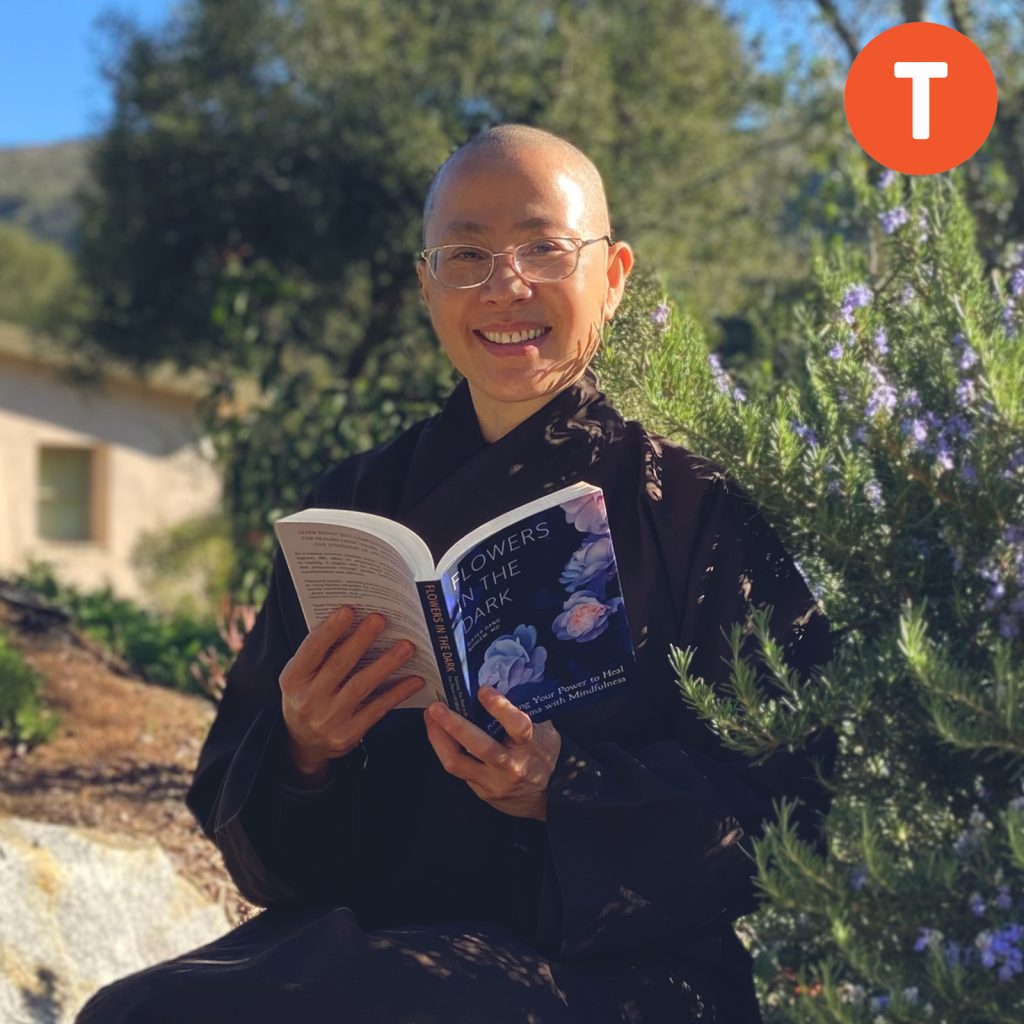

Born in Central Vietnam at the height of the Vietnam War, Sister Dang Nghiem grew up singing made-up songs to comfort herself and express her suffering. After moving to the US, she began writing poetry at the encouragement of an English teacher, and eventually, she ordained as a nun in the Plum Village tradition following the sudden death of her partner. Her latest book, The River in Me: Verses of Transformation, brings together over three decades of her poetry, charting her own journey from turmoil and loss to tranquility and compassion.

In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sits down with Sister D to discuss how writing has helped her process the violence she witnessed, why she hopes her poetry can offer not just a description of suffering but a way out of it, and how gathas, or verses, can transform mundane activities into moments of awareness.

Please note that this episode includes discussion of sexual abuse and suicide.

Tricycle Talks is a podcast series featuring leading voices in the contemporary Buddhist world. You can listen to more Tricycle Talks on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, and iHeartRadio.

♦

We’d love to hear your thoughts about our podcast. Write us at feedback@tricycle.org.

Read transcript

Sister Dang Nghiem: “Life without Boundaries” Safe to myself James Shaheen: Hello, and welcome to Tricycle Talks. I’m James Shaheen, and you just heard Sister Dang Nghiem, who goes by Sister D. Sister D has been a nun in the Plum Village tradition for over twenty years, and her work focuses on how mindfulness can help us transform grief and trauma into wisdom and insight. Her latest book, The River in Me: Verses of Transformation, brings together over three decades of her poetry, charting her own journey from turmoil and loss to tranquility and compassion. In my conversation with Sister D, we talk about her experience growing up in Saigon during the Vietnam War, how poetry has helped her process the violence she witnessed, why she left medical school to ordain as a nun in the Plum Village tradition, and how gathas, or verses, can transform mundane activities into moments of awareness. Plus, Sister D reads a few poems from her new collection. Please note that this episode includes discussion of sexual abuse and suicide. So here’s my conversation with Sister D. James Shaheen: OK, so I’m here with Sister Dang Nghiem, a nun in the Plum Village tradition. She goes by Sister D. So, hi Sister D, it’s great to be with you. Sister Dang Nghiem: Hello, James. Thank you for being there. I know you’re there, and I’m very grateful. James Shaheen: I’m grateful, too. So Sister D, we’re here to talk about your new poetry collection, The River in Me: Verses of Transformation. So, to start, could you tell us a little bit about the book and what inspired you to write it? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, I’ve written it over the last thirty years or so, this book. It’s an unfolding of my own life’s journey. I started to write as a teenager in Vietnam, here and there, just to express something deep inside of me that I had nobody to share with. And then when I came to the US, I started to learn English, and I went to college. There was an English teacher there, and she encouraged me to continue with my writing because she said even though my English needed a lot of work and yet my writing had substance. It had very deep meaning, and so in order to learn English and also to express myself, I continued to take creative writing classes, as well as English literature classes. They gave me a platform to express myself and what I was going through. So it helped me to process the suffering that I was experiencing that I was not able to articulate verbally very well. And so I continued with that even throughout medical school. However busy I was, every so often I would write something, and that has continued into my monastic life as well. So my writing is actually unknown to most people and most monastics. I would say only one or two are vaguely aware that I have been writing poetry. It’s just really for myself. James Shaheen: So you’ve been writing poetry for many decades at this point, and you say that as a child in Saigon, as you just mentioned, you would sing made-up songs to comfort yourself and express your suffering. So could you tell us a bit about your childhood? What was it that first drew you to poetry? Sister Dang Nghiem: I was born in Vietnam in 1968, so that was during a very intense period of the Vietnam War, or the Vietnamese people would call that Kháng chiến chống Mỹ, the War against the Americans. I was born as a result of the war, an Amerasian child. I had a Vietnamese mother and an American father, so my birth and then subsequently my brother’s birth, who is also Amerasian, was not very welcomed. It was during a turbulent time. My mother was not married, and she was not there to raise me or my brother, so my grandmother raised me and my brother mainly. So that’s already a lot for a child to carry within. I also experienced sexual abuse as a child, and then my mother disappeared when I was 12. So just a lot of unspoken suffering, the searing pain that I was experiencing in me as a child. But who could I communicate that to since there was not really anybody around to be my friend or to be my mentor, not even my own mother? So I started to make up songs about my daily life, about what I was feeling, and that was cathartic for me, and I remember one time I was singing to my brother, and we both cried. Writing songs and poetry was a dear friend to me, a soulmate to me at a very young age. James Shaheen: Yeah, you grew up during a very violent time, which is a theme you explore in depth in your earliest poems. How did writing help you process the violence you witnessed? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, writing started as a means for me to express my thoughts and feelings. It was the practice of mindfulness when I became a nun that actually helped me to process more deeply and to transform and heal that suffering. So for me, too, after all these years, I published this book, which is very intimate. I mean, I’ve published three books already about my life and my practice, but I feel that this collection of poetry is much more intimate, because you know how poetry can be so succinct, so direct, straightforward, and it just carries that essence. And so it’s my deepest aspiration to help others, to relay a very positive message in the midst of wars going on all over the world, of political division, of poverty, of injustice, of discrimination of all sorts in our world. People are very overwhelmed. I mean, I just had, I just gave a recent consultation, and the young woman filled out her slip, “Not sure what happened to me!?” That was all she wrote on the consultation slip: “Not sure what happened to me!?” And I think that’s prevalent in our world right now. So I want to express not just suffering but also the way out of suffering, and the mindfulness practice, the spiritual life has enabled me to do that over the last 24 years as I’ve been a monastic practitioner. James Shaheen: You know, as I mentioned before we started, I invite you to read a poem if it helps to explain further what you were saying. Sister Dang Nghiem: I’d like to read a poem called “Grandma,” just to see my background a little more clearly. This poem, actually, I wrote in medical school, and I won an award for it. An award, the William Carlos Williams Poetry Award, yeah, and it means a whole lot to me. It’s the first poem in the poetry collection. “Grandma” Once I asked if you loved me. Once I kissed your cheeks and tasted And the day I left you for America, I was sixteen and a half when I left Vietnam with a five-dollar bill I wanted to send you a waterbed, so you could float gently to your sleep; I did not send you medicine, The day I heard you died, I looked at my face, Half belonged to my mother, James Shaheen: Thank you, Sister D, that was lovely. You say that it was your grandmother who first encouraged you to become a nun and that she herself once wanted to become a nun. How did this influence your life path? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, Grandmother, thankfully, was very spiritual and wise. She was prophetic, because since I was eight, and especially before I left Vietnam for the US, I was 16 and a half then, Grandmother reiterated her wishes to me. First of all, she wished that I help raise my brother to become a good person in the world. Secondly, grandmother wanted me to achieve higher, to strive for higher education, which I did. And the third one, grandmother said that she wanted me to become a nun. That was the way to freedom, Grandmother said to me. And I diligently carried out my duties, my grandmother’s wishes. My brother is a wonderful, loving, hard-working person. I graduated from college, from medical school, but the third one I never really understood, even when I was in medical school, especially in medical school, because I felt like, why would you become a nun when you have achieved so much? it didn’t make sense in the modern times. But when my partner passed away, I understood. I achieved everything I worked hard for, thinking that it would bring me happiness. But when he died, I saw very clearly my academic success, my worldly success, did not bring me true, long-lasting happiness. I was still drowned in my sorrow, my sadness, my trauma, and I also continually walked away from the sources of happiness, like a stable relationship, a loving partner, and I just curled up with my pain instead. So the death of my partner woke me up to that reality, and thankfully, I met our teacher, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, only three weeks before John passed away, and so I actually saw there was a possibility. Instead of committing suicide, I saw that I could make a choice for a life of peace, and my grandmother had chosen that life since I was a child, although she had to raise my brother and me, in the absence of my mother. But my grandmother was spiritual and she was wise, and the image of her sitting peacefully on the plank bed, it’s a wooden bed, doing the rosary and praying and chanting, that image was very strong in me so that for many years when I was living in the US and I was going through episodes of depression, episodes of suicidal ideation, I would see that image of my grandmother sitting so stably on the plank bed. or in front of the altar. Even in my dreams, I would dream of Grandmother, and her presence would soothe me and stabilize me so that in the morning I could get up and continue with my medical training, et cetera. So I have learned that all of us would go through certain difficulties, trials, and tribulations in our life, some of us more, some of us a little less, but we all go through. But the blessing that we may have is a stable figure in our life who’s spiritual, who’s stable, who has a purpose, a direction/ That can save our life. And my grandmother was that early figure in my life, and later John served that for me as a partner and also as a spiritual practitioner. John was very spiritual as well. And that also gave me peace when he died: I didn’t just think of death and suicide. I actually remembered how spiritual he was. And if I were to die in despair, I would never be able to see him again, if there were another life. And then later, my teacher, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, became the most influential figure in my life, in my spiritual life. I feel that I have been so blessed with Grandmother, and then with John and then with Thay, our teacher. And my practice helps me to transform and heal my own pain and also helps me to be that stable figure for many young people that I have met in my monastic life and also that they meet me through my writing of my books and poetry. James Shaheen: So you were midway through your residency, your medical residency, when you decided to become a nun, and you just talked about the precipitating event, the loss of your partner. Would you like to read anything about that? Sister Dang Nghiem: I’d like to read one poem, “The Body.” I wrote this during medical school. It’s very short. “The Body” Here is the body of a young woman. So this poem, when I wrote it, and as I went through all my poems to select them for this poetry collection, I saw some recurring themes, and one is of sexual abuse. There were many poems where predominantly the theme is of sexual abuse and also of losses, but sexual abuse is actually more prevalent in my writing. And I was struggling with that throughout my life, and that also affected my relationship. And so in the monastic life, I have learned to transform that deep pain. James Shaheen: So you wrote that poem in medical school, and as a nun, you have continued to write poetry. And this book brings together two collections, the first from before you ordained, and the second from after. How do you view the relationship between these two bodies of work? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, in many ways, it’s a continuum. It’s my life’s journey before the practice and while practicing. As I go back to my journals and my poems, I see that already way back then, I had many insights about my situation, but I didn’t see a way out. And I think that’s true for most writers. In college, I signed up to take this poetry class and it was difficult to get in. The instructor was very popular. His name was Joe Bolton, an American poet. I went to his class only a couple of times, and he already paid attention to me and encouraged me with my writing. And I think it was only the third class, I came to, I came to the class and was told that he just committed suicide. And that really hurt me and confused me. I really appreciated his poetry, and I saw very clearly through his poetry, through mine and many other writers, we can express suffering eloquently and poignantly, but many of us didn’t know the way out. So in Buddhism, actually, as we practice, we realize that we can water the seed of suffering if all we consume through our six senses, the eyes, the ears, the nose, the mouth, the body, the thoughts, the views, if we only consume suffering but we don’t see a way out, we don’t know how to transform, heal it, resolve it in our daily life, and that’s like watering the plant of suffering, and it will become a tree, and very deeply rooted in our consciousness. So I hold Joe deeply in my heart, and I also feel like my transformation and healing is also for him, and many writers, and I hope that this transformation and healing and the writing that expresses the way of practice can inspire many people and generations to come so that we write from that angle and not just to express eloquently our suffering. James Shaheen: You mentioned healing, and you write that these two collections feel like the before and after stages of a commitment to heal. What do you mean by that? Sister Dang Nghiem: Oh, here I have a poem that may be able to express that. One is sloughing off. “Sloughing Off” These days I enjoy This is not easy because we are very much trapped in our thinking and in our feelings, so to be able to simply be is a very deep practice, and to entrust ourselves in Mother Earth’s womb and not to feel that our feeling is ours alone and that we have a separate existence from everybody else and our suffering is our own. So it’s to be able to be there with the suffering, to rock with it, to curl with it, and to be embraced by the energy of mindfulness, by Mother Earth, and to slough off all of that suffering is a deep practice. One more poem about a recurring dream I had, a recurring dream about running, about getting lost, not knowing where I am, being left behind. It’s a very deep fear, deep suffering in me. “Stopping” Yet another dream Running late again People all around Suddenly The hubbub Utterly still. James Shaheen: Thank you. So you just mentioned mindfulness, and you say that while writing has played a role in your healing, writing in itself won’t change your life; mindfulness will. Why is this so, and how has mindfulness changed your life? Sister Dang Nghiem: Every moment that we live mindfully, every mindful moment, is a live poem. It’s a lived poem. I learned to live in the present moment, in the here and the now, to see my suffering not just through the lens of the past but right here and right now. It’s manifesting. For example, the way of thinking to see oneself as a victim, it continues in the present moment. The way we think, the way we feel, the way we speak, the way we behave—it’s like we are a wounded child, even though we have an adult body right now. And with mindfulness, I’m able to recognize that, to make that discernment: That’s the thinking, the speech, and the behavior of a wounded child. And yet, in this moment, I’m an adult fully capable of taking care of myself. So I breathe, I smile, I send love and attention and care to that wounded child. And in that moment, it’s like a wave on its way to build up as a big wave or as a tsunami. With awareness, with simple recognition and mindful breathing, I can subside, the wave can subside. I can soothe that wave. It can go back to its original place, that seat of despair, of confusion, of helplessness. It can be embraced. And there’s actually confidence, there’s actually trust and faith in myself that I can care for my inner child bit by bit, moment to moment. I have done that, and that helps transform my suffering. So writing is important in the sense that we express our loss, our despair, our confusion, but if we also realize transformation and healing in our daily life, it will also naturally be expressed in our writing, and that also inspires hope and confidence in others. James Shaheen: You know, I’m thinking about your mention of watering the seeds of suffering, but here you write, “Instead of simply writing about suffering, my words began to share a way out of suffering.” Can you say more about this shift? Sister Dang Nghiem: Yes, that actually came very slowly as I went to Plum Village and became an aspirant before I ordained as a nun. Even into my monastic life for the first seven years, I cried a lot, particularly the first four years. I was infamous for my crying. Anywhere, public or private, day or night, I would be crying, and it came from, it’s like a dam broken, and I couldn’t really contain it anymore, but I didn’t want to get caught and trapped in my suffering, like when I was in my lay life, so I also took to heart the practice of mindful breathing and mindful walking. Slowly, I experienced respite from just searing pain. When I was breathing, my mind was with my breathing, with my body, even if momentarily, instead of being completely drowned and drenched in suffering. I experienced peace in the midst of suffering, and that was expressed in my writing as well, slowly and slowly. I don’t have the poem here with me, but in one poem, it’s a long poem, I shared about this young woman who came to Plum Village, and she slashed her wrists, all over her wrists and her calves. And I was suffering myself, and I heard the bell for dinner, but I went to the meditation hall instead, and I just sat there, and I actually practiced the sixteen exercises of mindful breathing, so when you read through that poem, it’s actually sixteen exercises of mindful breathing, starting with following the breath and then aware of the body, relaxing the body, and then becoming aware of the feelings and painful feelings and to embrace them and to just go part by part. During that whole period, because I also used to take refuge in food, that was one of my escapes was food to numb, to soothe my suffering, but that particular sitting, I took refuge in mindful breathing. I took refuge in my stable posture to embrace my pain and also the young woman’s pain. And I came out of it feeling much more relieved and more confident. I had more confidence for the practice, and that was expressed in that poem. And I have continued to do that all these years. Whenever suffering arises in me, or when I listen to the suffering of others, I continue to anchor my mind in mindful breathing so that I don’t bring that trauma into my own body and mind, or I don’t water and strengthen that seed of suffering in myself. Does it make sense? James Shaheen: Yeah, that makes sense. That shift from description of suffering to a way out of suffering is very evident in many of the poems you write. But that made perfect sense. One thing that surfaces again and again in the poems, and it’s no surprise, is loss, whether it’s the grief of relocation or of losing your mother and then your partner. How has revisiting these losses through your poetry shifted your relationship to grief, or has it? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, again, it’s the expression of the situation of the pain, but also the daily practice that helps me to shift my perspective. I have this particular poem, “Song for Mother.” My mother passed away when she was—she disappeared when she was 36 years old. “Song for Mother” This song is for you, my mother. This song is for you, my mother, This song is for you, my mother, These vows I make to you, my mother: So that’s my practice. When I did walking meditation, especially in the beginning, and I still do that sometimes now, I would say, “Mother, you never had a chance to walk leisurely, to not do anything, so now I walk leisurely. I walk in meditation for you.” And when I was doing sitting meditation, I would sit for my mother, who always had to hustle bustle, always had to go to this place and that place, to work all the time, who was tired and not happy, and that’s why she hit me, that’s why she screamed at me, that’s why she cursed at me. I realized that my mother didn’t hate me. She actually provided me and my brother all of the material comforts. If you see some of my pictures in the book, I was very well dressed as a child. That’s very unusual, wearing dresses and wearing nice shoes and all. My mother provided us well with material comfort. But the suffering she experienced, she didn’t know how to handle, and that was why it came out on me. It spilled all over me with her physical and verbal abuse. I had to endure all of that. And so I have learned to live a more peaceful life, more beautiful life, more gentle life, for my mother as well. She transformed in me. I had a dream for twenty years after my mother disappeared. My mother was always deaf and dumb in my dream. She walked right past me, but she never saw me. She never said anything to me. And I woke up feeling so upset, so abandoned, unseen, unheard by my mother. But as I practiced, only within two years, I had a dream about my mother, and she said something to me in the dream, and I woke up immediately, and I just cried because it was the very first time after twenty-some years that my mother saw me and she said something to me and that I saw my mother was actually transforming. My mother was actually being liberated from the prison of my own mind, because before that, when I thought of my mother, I only thought about her pain and her abuse, her suffering in her own life and the suffering she imposed on me. But as I practiced, I saw my mother peaceful in me, and in the dreams, she became more peaceful. And that’s the transformation, very deep transformation. James Shaheen: Do you remember what she said to you? You know, I don’t even remember what she said to me. The moment she said something, I just heard her voice, and I woke up, and it meant so much to me. And, actually, since then, here and there, I would dream of my mother, I would never hear her voice, but I would see her being peaceful, and that was more than enough for me. The very last dream I had about my mother, it was about a year ago or so, and she was curling up on her side, and I was lying right behind her cupping her, and my brother was right behind me cupping me, the three of us in peaceful silence, and I woke up and I felt so happy. I see so clearly my mother is at peace, is liberated right inside of me, and she is me. My mother is me. And I’d like to read to you this one poem, and it’s funny how, I mean, this is why I also appreciate poetry. When I write short stories or a book, it may take pages and pages to express something I would like to share. The challenge of writing a poem is that it may take only a few stanzas or just one stanza like this one, but it has taken me twenty-four years to realize this. “Life without Boundaries” Safe to myself So the view of victimization, of seeing oneself as a victim, perpetuates the suffering in ourselves and in the world. But when I learned that if I can be safe to myself in my thoughts, speech, and bodily actions, I don’t water the negative seeds in myself, I don’t hurt myself physically and mentally, I am safe to myself, then, not only I am safe in the world, but I am safe to the world. I don’t spill my suffering on others. I don’t cause other people suffering the way that others have caused me suffering. So this poem is a very deep realization and what in Zen we would call a gatha. It can be considered as a gatha, if you want to know more about gathas. James Shaheen: Actually, I do, because you say that in the Plum Village tradition, you write insight gathas, or verses that convey your deepest aspirations and point the way toward happiness. So first, for our listeners who don’t know, what is a gatha, and what have you learned from reading and writing these verses? Sister Dang Nghiem: Well, the tradition goes way back. Even in the time of the Buddha, the monks and nuns who achieved deep insight, when they achieve actually enlightenment as arahants, they would leave behind them poetry. We call them gathas, and you can find many gathas from enlightened monks and nuns, and interestingly enough, there are more enlightened gathas written by nuns than by monks in the time of the Buddha that you can look up called Therigatha, by bhikshunis, fully ordained nuns. It’s a whole collection of that. And so it’s rooted in the Buddha’s time, and then many Zen masters throughout the centuries also write poetry considered as poems of liberation or enlightened poems or gathas. So many Zen masters have those poems as well. That’s in the Zen tradition, and our teacher has continued that. When we, each one of us, we become dharma teachers, there’s a ceremony, and we write an insight gatha to present that to our teacher, Thay, and to the community, “This is my insight gatha.” And Thay would respond with a gatha called transmission gatha. Gatha means poem or verse in the Buddhist tradition, and Thay would respond with one, and I actually have an insight gatha in my poetry collection as well. And that moment I wrote about, that was my dealing with John’s death. I was walking to the big meditation hall here at Deer Park about 2007 because I presented this insight gatha in 2008 to Thay and the community. So I was walking to the meditation hall and I passed by these trees, and they had these flowers, they’re called oleanders, oleander flowers. And as I walked by, this one flower bud just dropped right in front of me. And, of course, I’ve seen flower buds falling from the tree many times before, but that moment, because I was mindful, I was truly present, I bent down, I picked up that bud, and I looked at it, and I saw that a flower can fall at any stage. When it’s just a bud, not only when it’s fully bloomed or wilted, but as a bud, it can still fall. And that was a moment of enlightenment for me. Of course, I had that knowledge for many years, but the moment when you are truly present, and you touch something so deeply, the truth of it, it shakes. It’s like the image in Buddhism, the Buddha, when he became enlightened, or when he passed away, the earth quaked seven times. So it shook seven times in me in the sense that I saw that John’s life is like that too, and my mother’s life is like that, and many lives die young, and that is a part of nature. But how do we live in such a way that life can continue just like the Buddha who passed away 2,600 years ago? But the Buddha is very much alive in many of us, in our practice, in the teaching. So then I wrote that poem as an insight gatha. James Shaheen: Do you happen to have that poem with you? It’s very auspiciously on page 108. Sister Dang Nghiem: 108, yes. “Insight Gatha” A flower falls, thousands continuing. James Shaheen: Thank you. I’m so glad we found that one. Sister Dang Nghiem: Yes. James Shaheen: So at the back of the book, you include a number of gathas for everyday activities, like washing your hands or brushing your teeth. Can you say more about these gathas? How can they transform mundane activities into moments of spiritual practice and awareness? Sister Dang Nghiem: In the Zen tradition, the mundane becomes the extraordinary when there is mindfulness, where there’s stopping and deep looking. So in that way our practice helps us to be awakened and enlightened in our daily life and in our daily activity, and so things like putting on clothes, washing hands, brushing teeth, they are so mundane that we do them automatically, and yet in the depth of our consciousness, we continue to think and to generate negative thoughts and very strong emotions. But if the mind can anchor in what it’s doing, then the mind is not generating suffering, but the mind is generating awareness, peace, and gratitude. For example, this gatha for brushing teeth: “Gatha for Brushing Teeth” I’ve been given this day, See, it’s very simple, but like our practice, for example, we learn to celebrate a non-toothache moment. Most people take that for granted. When you don’t have a toothache, it’s a neutral feeling, you don’t appreciate it, but when you have a toothache, all you wish is for your toothache to go away, So we learn to turn a neutral moment, feeling a neutral moment, like while you’re brushing teeth, into a happy moment: I’ve been given this day to have teeth to brush, to have reasons to smile.” So another gatha that I wrote, “Gatha for Going to Sleep”: “Gatha for Going to Sleep” I vow to bring awareness For most people, we would work until the very last moment before we go to sleep, and our mind is very active, and in our sleep, our mind is not resting. It continues to generate thoughts and feelings, nightmares, confusion, and so we don’t have enough awareness how important it is that the quality of our sleep affects our daily life, our healing and transformation. To be able to bring awareness into my sleep, I have to generate it in my daily life so that my recurring dream of getting lost, not knowing where I am, or being chased by a man. In my daily life, I have mindfulness. I bring that into the night. Then I practice stopping. Even in my sleep, I say to myself, “I don’t have to run anymore. I don’t have to go anywhere.” I saw a man running, chasing after me, and at one moment, I actually stopped and looked straight at him instead of running, and in my dream, he was so shocked, he just stopped, and then he walked out of that door while I closed the door gently. So the energy of mindfulness in the daytime is translated and brought into the night, and we change our habitual way of thinking and reacting, and that is transformation at the base. When you can, When that happens in our dreams, that is the deepest transformation, and it reflects that healing in our store consciousness, in the depth of our consciousness. James Shaheen: Thank you, Sister D. Is there anything else you’d like to say before we close? That was lovely. Sister Dang Nghiem: Thank you, dear James and all of you, for making this happen because I really hope that this book of poetry will reach as many people as possible. I know there are those who enjoy poetry more than reading prose. I also hope that health professionals also get to read this book so that, again, to bring the message of healing and transformation to a world that is so darkened by despair and confusion and division. So thank you for helping to make it possible, my dear ones. I really appreciate that. James Shaheen: Well, thank you so much for joining us. It’s been a great pleasure for me and I’m sure for our listeners too. For our listeners, please be sure to pick up a copy of The River In Me, available for pre-order now. Thanks again, Sister D. Sister Dang Nghiem: Thank you so much, James. Thank you so much for all the listeners. Please help pass the message. James Shaheen: Thank you. Sister Dang Nghiem: Thank you. Bless you. James Shaheen: You’ve been listening to Tricycle Talks with Sister Dang Nghiem. Tricycle is a nonprofit educational organization dedicated to making Buddhist teachings and practices broadly available, and we are pleased to offer our podcasts freely. If you would like to support the podcast, please consider subscribing to Tricycle or making a donation at tricycle.org/donate. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast, so write us at feedback@tricycle.org to let us know what you think. If you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. To keep up with the show, you can follow Tricycle Talks wherever you listen to podcasts. Tricycle Talks is produced by Sarah Fleming and the Podglomerate. I’m James Shaheen, editor-in-chief of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Thanks for listening!

I am safe to the world.

At ease in myself

I am at ease in the world.

At home in myself

I am at home in the world.

Healing myself

Is healing you

Deep within.

You laughed and questioned who would love

My dog-born face.

Then you turned away to cough,

And I awkwardly reached for your back.

Grooves of your skin between my lips.

You hit my teenage pimple with your quivering fist.

I laughed and dabbed my tears.

You placed my hands in your spread-out palm.

You spit chewed betel juice and circled it slowly on my hands,

Saying: “This is to help you not to miss Grandma too much.”

You refused to go to the airport.

And a few English greeting phrases.

From America, I wanted to send you newspapers and Smitty’s plastic bags,

So you could sell them by the gram;

People threw them away here.

Your seventy-five-year-old body would not have to strike

Against the wooden plank bed anymore.

I worked the midnight shift at a post office to send you dollars,

Bars of soap,

White laces,

Bottles of green oil.

But prayers. Every night, I prayed for you,

While I listened to the echo of your constant coughing,

Of the hard thumps against your aching body.

Half to an unknown man,

And I cried with a fist, yours,

In my mouth.

Here is a child trapped inside the body.

It watches the body make sex,

While it thinks of ways to escape.

Lying on a hammock

My body curls

Like a fetus, gently swaying

In Mother Earth’s womb

All my doings slough off

I

simply

be

Trying to leave here

To go somewhere

Safer, better

Panic

Scattered

Yet distant

Unreal

A thought arose,

No need to go

Anywhere

I’m already

There!

Vanished

It has been a long time since I last saw you.

You were thirty-six when you walked

Out and never came back.

Now I am thirty-five, looking at myself

To find you.

Whom I hated and blamed for

All my pain.

Now I learn to understand

Your suffering and embrace

Your struggles in me.

Who gave me this beautiful smile,

This sadness,

This anger,

Who gave me this generosity,

Self-determination.

All the beautiful seeds

You have planted in me,

I vow to cultivate and share.

All the negative traits

You have transmitted to me, I vow to transform and

Heal, you in me.

I am safe to the world.

At ease in myself

I am at ease in the world.

At home in myself

I am at home in the world.

Healing myself

Is healing you

Deep within.

A song fades, birds singing out of space.

The heart of love illuminates in the sea of fire,

Fulfilling its vow with the ancient moon.

To have teeth to brush.

To have reasons to smile.

Into my sleep this night,

To dispel all fears,

To see emptiness in all desires,

To find my way out with mindfulness,

To know what is reality, what is illusory.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.