Dominique Butet and Olivier Adam have been interviewing and photographing Tibetan nuns as a way to document their daily lives and differentiate women monastics, who are often mistaken for monks by Westerners.

Adam first began visiting the nuns in 2008; Butet teamed up with him in 2010. As the nuns gained increasing access to education, issues of gender equality played out before the documentarians’ eyes.

Below is a series of photographs from Adam’s “Daughters of Buddha” series, with reportage by Butet. They plan to publish a book in 2017 and continue documenting Tibetan Buddhist nuns in Bhutan and Nepal.

—Wendy Joan Biddlecombe, Web Editor

Our project began in Dharamsala, the northern Indian city where thousands of Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama into exile in 1959.

Rinchen Khando, the sister-in-law of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, created the Tibetan Nuns Project in 1987 to give the exiled women and the nuns from Himalayan regions accommodation and education.

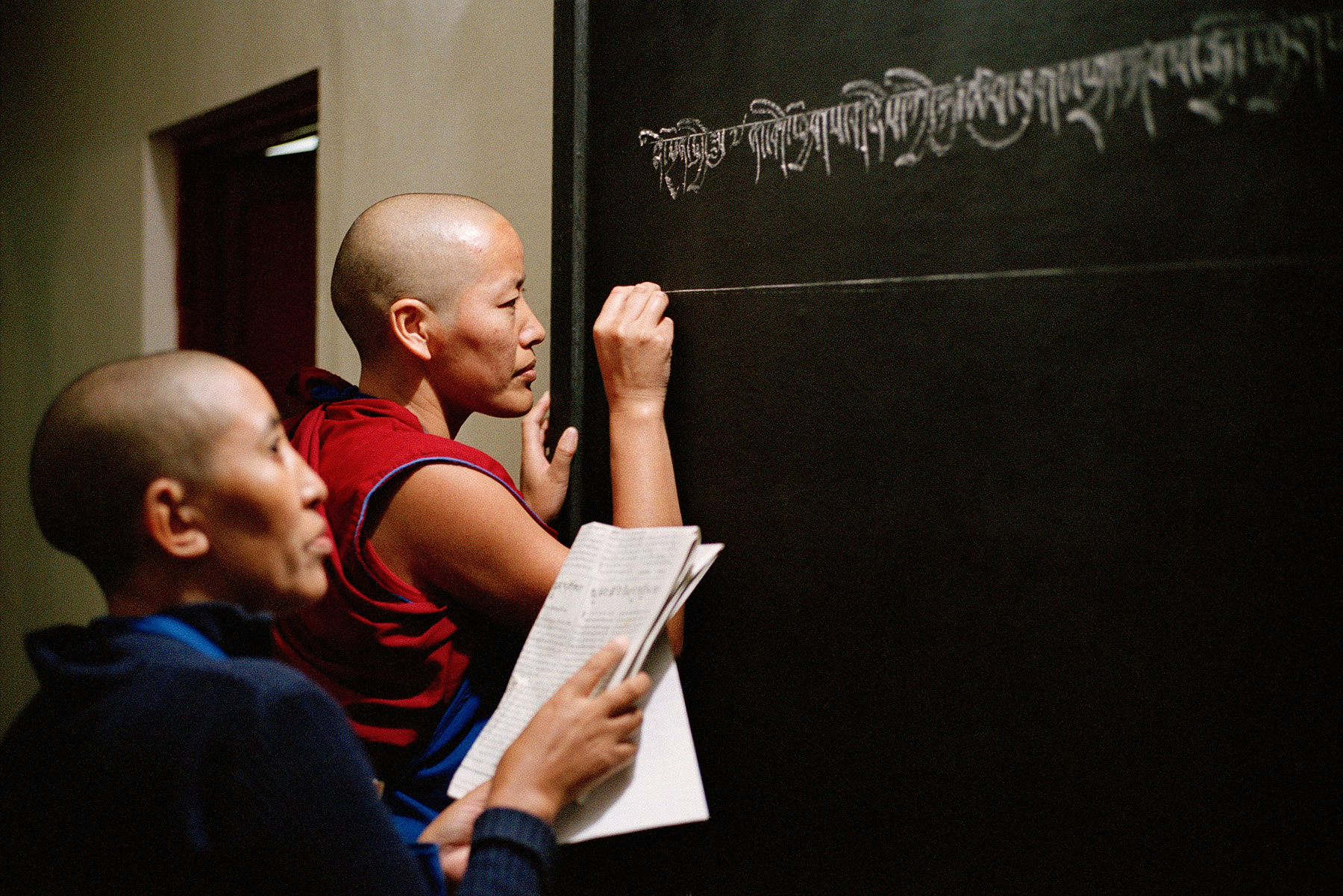

The nuns’ level of education progressed over the years, and in the early 1990s they began the practice of formal debate—a philosophical tradition previously available only to monks. In 2012, the Dalai Lama made the historic decision to allow geshema exams for nuns. The geshema degree is equivalent to a PhD in Buddhist philosophy and is conferred after 17 years of study.

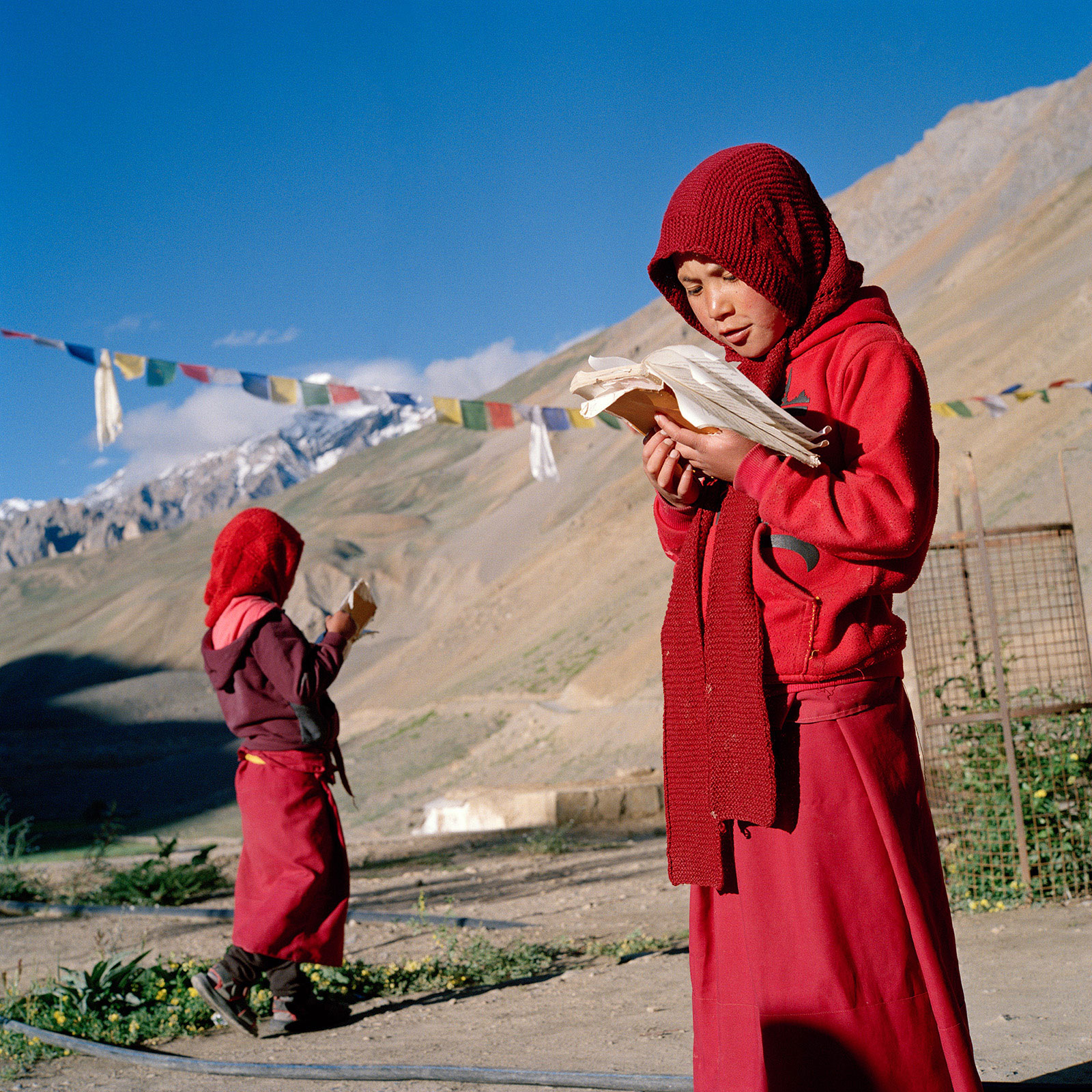

We moved north from Dharamsala to the high valleys of the northwestern Himalayas. Living conditions on the nearly 2.5-mile-high slopes there are harsh, especially in the winter.

There are 10 convents in Zanskar, a district in India’s Jammu and Kashmir state—small structures that house about 20 nuns who aspired to build schools in the area. In the summer of 2012, the seven nuns at Dorje Dzong Nunnery, two of whom were more than 80 years old, began the ambitious project of building their own school.

For weeks on end, they tirelessly took part in its construction, shoveling and transporting sand, making earth bricks, cutting wood, and supporting the team of workers at the site. Two years later, the school opened and 17 young nuns started studying Tibetan, English, Hindi, and math. Similar efforts to educate nuns continue in Zanskar’s other nunneries.

In Spiti, about 150 miles east of Zanskar in Himachal Pradesh, there are four communities of nuns established less than 30 years ago. Before that, the nuns either lived with their families or in caves as hermits.

The creation of nunneries goes hand-in-hand with that of the schools, but not without difficulties. Tseten became a nun in Yangchen Chöling Nunnery in Spiti in 1996. She remembers: “It took a long time to find a teacher willing to teach nuns. Finally, a kind monk agreed to come and teach at our monastery. For several months, we all studied happily together. Suddenly, the monks of his monastery arrived and told him he could no longer teach nuns. All the nuns and the teacher, too, became sad and distraught. Finally, he agreed to resign from his monastery and stay with us at the nunnery.”

[This story was first published in 2016]

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.