HOLY MADNESS: PORTRAITS OF TANTRIC SIDDHAS

The Rubin Museum of Art

New York, through September 4, 2006

THERE HAS BEEN a growing misconception in recent years—thanks in part to a glut of how-to videos, an expanding procession of “tantric healers” offering their services on an hourly basis, and the well-publicized adventures of several rock stars and celebrities—that the New Age phenomena of “tantric sex” is legitamately linked to the centuries-old spiritual practice of Tantric Buddhism. While the former is a trendy erotic pastime, the latter is an esoteric system for achieving enlightenment in one lifetime, rooted in northern Indian Vajrayana Buddhism and dating back to the seventh century. An engaging and highly accessible exhibition, “Holy Madness: Portraits of Tantric Siddhas,” on view through September 4th at New York’s Rubin Museum of Art, goes a long way in dispelling any false association of so-called tantric sex with Tantric Buddhism. The show, featuring more than one hundred objects, is a broad overview of how artists throughout the centuries have portrayed siddhas, or highly accomplished practitioners of Tantra.

The works on view consistently characterize Tantric siddhas as wild-haired mystics, flamboyant and iconoclastic, not unlike today’s rock stars. Tantric siddhas believed that their enigmatic rituals—sometimes involving sex and mind-altering substances—would allow them to break free of worldly desires by indulging in them. Tantric doctrine promised a very rock-’n’-roll, live-fast, die-enlightened approach to practice, as opposed to the slower, process-driven forms of Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism.

The organizers of “Holy Madness” took on an ambitious and groundbreaking challenge: to trace, via extensive scholarly research, the spread of Tantric Buddhism from India throughout the Himalayas. It was a difficult task, because Tantric practices have always been intentionally mysterious, and thus linear historical documentation is scarce. So the curators gathered a wide variety of art-historical objects to cleverly thread together visual and thematic depictions of idealized siddha figures, or mahasiddhas (maha translates as “great”). Their art-historical detective work has resulted in a loose narrative focused on the siddha as the messenger of Tantric Buddhism. Like a string of pearls, the works on view—which include paintings, sculptures, prints, manuscripts, tapestries, and photographs gathered from a variety of institutional and private collections around the world—come together elegantly.

Introductory wall text neatly condenses and lists the key components of tantra: rituals, yoga, the student-teacher relationship, esoteric behavior, and, yes, sex. The show includes a spectrum of “firsts” or “only known examples” of their kind, along with various regional interpretations of recurring tantric narratives like that of Virupa, aka “The Ugly One,” a potbellied party-boy mahasiddha with crazy eyes and hair piled in a signature top-knot, best known for stopping the onset of day to avoid paying his bar bill.

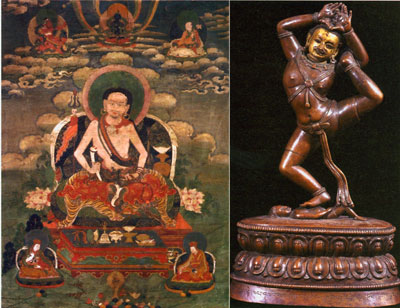

Virupa appears again and again in various guises, but the recurring narrative of this popular figure, whose mental determination to halt the sun from rising can be seen as a metaphor for the power of meditation, never grows dull. Other mahasiddhas—the primordial Buddha Vajradhara and the tenth-century yogi Jalandhara, for example—are depicted over and over as well. The curators’ careful mix of genres, eras, and geographical styles generates a pleasing sense of rhythm and showcases the transnational popularity of iconic mahasiddhas. Jalandhara, for example, recurs in the same contorted pose but in highly different forms, including a playful sixteenth-century Tibetan metal statue and as the central figure in an open, airy painting from nineteenth-century Eastern Tibet that recalls Chinese landscape techniques.

Notable works include Virupa Surrounded by Great Mahasiddhas, a thirteenth-century Tibetan painting, the earliest known image from the Himalayas to depict a leading figure as physically larger than all others—a stylistic detail that later became a characteristic trait of mahasiddha imagery. A particularly effective display that exemplifies the exhibition’s adventurous breadth features a terra-cotta sculpture of Manibhadra, a female mahasiddha who is depicted under the arc of a tree branch, juxtaposed with a similarly composed sculpture of the male king Kirapala, who attained siddhahood. The curators conclude that the pieces, belonging to two different museums, are both from the same series of the classic eighty-four mahasiddhas made in Nepal around the fourteenth century.

The exhibition also includes three-dimensional objects used in spiritual practice, such as a stunning bronze twelfth-century Indian mandala in the shape of a lotus, that offer a palpable connection to the Tantric traditions of the past. And a selection of photographs draws connections between the original siddhas and their possible heirs in today’s world. Images by the late photographer Raghubir Singh, for example, capture the eccentric appearance of sadhus, modern-day Indian ascetics who often wear their long matted hair in top-knots. When these contemporary photographs are seen in the context of the historical paintings and sculptures of siddhas with strikingly similar looks, it’s easy to understand that the sadhus could be considered the scion of the earlier Tantric siddhas.

As a whole, the well-organized show provides a lively and illuminating visual history of Tantric Buddhism’s early spread throughout the Himalayas. Thanks to the curators’ bold scholarship, the exhibition also provides audiences with a highly informed view of how true Tantric spiritual practices and representations have evolved—and endured—over the years.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.