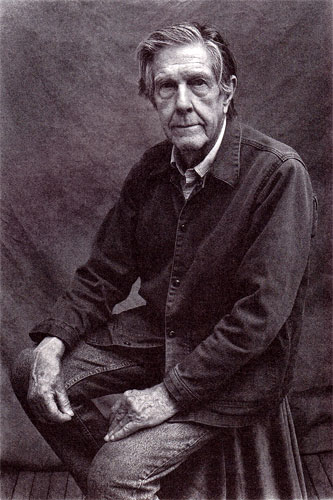

Eighty-year-old John Cage seems more clearly than ever to be the single indispensable figure in the experimental culture of the postwar era. As philosopher and provocateur, multidisciplinary artist and father of contemporary chance-determined music, Cage has inspired generations of artists East and West to bridge the gaps between Art and Life. The prime catalyst of this “Cagean revolution” was Zen Buddhism, specifically Cage’s attendance (from 1949 to 1951) at D.T. Suzuki’s classes at Columbia University. Suzuki’s first class in New York, the reigning cultural capital, concerned itself with the Buddha’s final teachings, emphasizing the interdependence of all things in a world of phenomenal abundance. This was the world and sensibility that Cage embraced in all his subsequent writings and works, doing as much to introduce a deliberately Buddhist view into the cultural discourse of the West as any artist alive.

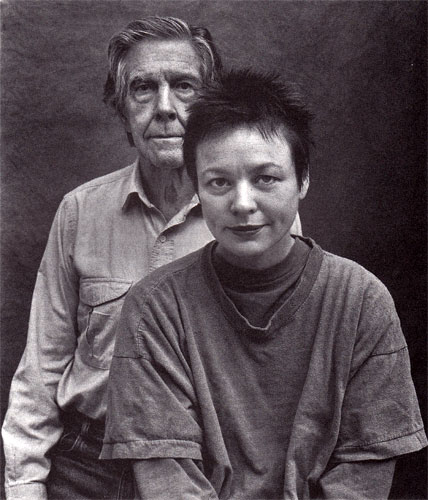

Laurie Anderson is even less conventionally Buddhist than John Cage. Her engagement with Buddhism, emerging from the SoHo art world of the seventies, has continued to be a strong personal interest two decades later. Widely identified as the artist who brought performance art into the cultural mainstream, Anderson works today as an activist, composer, filmmaker, photographer, raconteur, philosopher, and comic. Her newest project, a performance-opera entitled Halcyon Days: Stories from the Nerve Bible, is scheduled to open the Seville Festival this summer. Anderson initiated a discussion with Cage for Tricycle early in March 1992; I came for a second session not long afterward, joining them in his comfortable, sky-lit New York City loft, surrounded by abundant houseplants, paintings, and books, and drinking his Cafix—a fig and grain beverage that Laurie also drinks at home. Their common ground was wide: irreverent, funny, and terrific company, both epitomize ideals of cultural leadership and the phenomenon of the avant-garde. —Robert Coe

Robert Coe’s book Post-Shock: The Emergence of the American Avant-garde will be published by W. W. Norton this year.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

A: You seem like such a hopeful person, do you think human beings are somehow getting better?

C: What can we say but yes. There’s no other answer.

A: To go on? To be able to go on?

C: Not to be able to go on, but to go on. As D.T. Suzuki said once, “There seems to be a tendency toward the good.” Isn’t that beautiful? There seems to be a tendency toward the good. He never explained what he meant. And we never asked him.

A: What led you to study with him?

C: I was very fortunate. I had read The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. I became interested, in other words, in Oriental thought. And I read also a short book by Aldous Huxley, called The Perennial Philosophy, and from that I got the idea that all the various religions were saying the same thing but had different flavors. For instance, Ramakrishna spoke of God as a lake of people coming to the shores because they were thirsty. So I browsed, as it were, and found a flavor I liked and it was that of Zen Buddhism. It was then that Suzuki came to New York to teach, and I was able to go to Columbia once a week for two years to attend his classes, which were, if I remember correctly, at 4:30 in the afternoon.

A: Pleasant time of day.

C. Suzuki was not very talkative. He would frequently say nothing that you could put your finger on. Now and then he would. When I say now and then I mean one Friday or another, but on any given day, nothing that you could remember would remain.

C: Once in Hawaii, at a meeting of philosophers sitting around a table discussing reality, several days passed and Suzuki said nothing. And finally the chairman said, “You’ve been silent all this time. Would you say something about reality.” And Suzuki didn’t say anything. I think he may have looked up. Finally the man said, “Well, is this table real?” And Suzuki said, “Yes.” And then the man said, “In what sense is it real?” And Suzuki said, “In every sense.”

A: When the Dalai Lama was at Madison Square Garden [for the Kalachakra Initation in October, 1991] a lot of people asked him questions but they were not questions. They were really things to show him what they knew. So you’d listen to these questions and the people asking them didn’t want to know anything. Then came the last question. The Dalai Lama was on a big stage with all the lamas and there was a big golden pagoda on the stage, closed. All these people were asking questions, very esoteric questions about Buddhism, and he was being very generous about answering them. But the best question was, “What’s in the yellow pagoda?” It was such an obvious question. This big thing was sitting there and nobody would ask what was inside of it. He just described what the sand painting was like that they were working on inside. And it changed everything. It was the only honest question at the Kalachakra…. The teachings were tricky. They would almost trick people into taking vows. I took one. I promised to be kind for the rest of my life. I walked out the door and said what does this mean? Then a friend got a hold of a monk, and she said, “Did I promise too much, too little?” He told her, “You know, the mind is a wild white horse, and when you build a corral for it, make sure it’s not too small.” He was so practical. The Dalai Lama was saying that he felt very fortunate to have earned so many merits in his past lives, and that that was the reason he was having such an enjoyable life…. Do you feel that someone before you gathered merits so that you could have an enjoyable life or that you’re gathering ones so that someone, your descendants, can have one too?

C: I don’t have any knowledge of that.

A: So you’re not curious?

C: I’m not curious.

C: The big difference between the city and the country is the sound of traffic and the sound of birds. Actually, I find the sound of traffic not as intruding, really, as the sound of birds. I was amazed when I moved to the country to discover how emphatic the birds were for the ears.

A: You mean because they range in melody?

C: No. Because they were so loud. And they really compete with the sirens when they fly around and come close…

A: In using chance operations, did you ever feel that something didn’t work as well as you wanted?

C: No. In such circumstances I thought the thing that needs changing is me—you know—the thinking through. If it was something I didn’t like, it was clearly a situation in which I could change toward the liking rather than getting rid of it.

A: Would you think of it as a kind of design whose rules you just couldn’t understand?

C: I was already thinking of one rather than two, so that I wasn’t involved in that relationship. And that what was actually annoying me was the cropping up of an old relationship, which seemed at first to be out of place. But then, once it was accepted, it was extraordinarily productive of space. A kind of emptiness that invites, not what you are doing, but all that you’re not doing into your awareness and your enjoyment.

A: So you did, in fact, make a kind of judgment on yourself.

C: Yes, instead of wiping out what I didn’t like, I tried to change myself so that I could use it.

C: I keep manuscripts that are clearly no good because they must have some reason for existing too.

A: In what sense do you mean no good?

C: Not interesting. Where the ideas aren’t radical, where they don’t have likeliness or—what Bob Rauschenberg says— “they don’t change you.” And I think that the idea of change, or the ego itself changing direction, is implicit in Suzuki’s understanding of the effect of Buddhism on the structure of the mind. I use chance operations instead of operating according to my likes and dislikes. I use my work to change myself and I accept what the chance operations say. The I Ching says that if you don’t accept the chance operations you have no right to use them. Which is very clear, so that’s what I do.

A: How has the response to your work changed over the years?

C: Well, I don’t have to persuade people to be interested. So many people are interested now that it keeps me from continuing really. I asked a former assistant a few days ago how I should behave about my mail that is so extensive and takes so much time to answer? If I don’t answer it honorably, I mean to say, paying attention to it, then I’m not being very Buddhist. It seems to me I have to give as much honor to one letter as to another. Or at least I should pay attention to all the things that happen.

A: What did you decide to do about it?

C: To consider that one function in life is to answer the mail.

A: But it could take the whole day.

C: But you see, in the meanwhile, I’ve found a way of writing music which is very fast. So that if we take all things as though they were Buddha, they’re not to be sneezed at but they’re to be enjoyed and honored.

A: But this is a huge challenge.

C: It’s a great challenge. The telephone, for instance, is not just a telephone. It’s as if it were Creation calling or Buddha calling. You don’t know who’s on the other end of the line.

C: The question of social activism is a large question because it has so many different kinds of actions. I prefer to do what I’m doing for itself rather than to do what I’m doing for another reason. If I want to help say, getting rid of AIDS, it would seem to me more effective to support the research than to change the music.

A: Yeah, although a lot of artists say the opposite. They say, “Well, I’m going to work on it in my own way in my work.” How does that convince people or help them? I think giving money to research is so practical.

C: That’s how I do it. Rather than complaining about the politics, I think that we should become actively disinterested in government. It seems to be the most active thing to do now.

A: It’s been so confusing to me the last few months trying to get involved in politics and going “I don’t know….really I’m not very good at this.” And yet, I can’t say I should just do it in my work.

C: No, I think you can. I think your work is very, very important and very much used by society. This is the marvelous thing. Because you can perform and be seen, you see. I mean, the flow is taking place and you can increase it.

A: For me, being in a political group, particularly a women’s group, is sort of like answering mail. I feel that I should do this—I should be there.

C: It gives you a sense of responsibility.

A: Yeah.

C: But your real responsibility is the one that you discover. However you work. Your best work is what you yourself discover.

♦

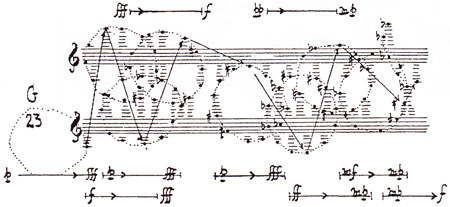

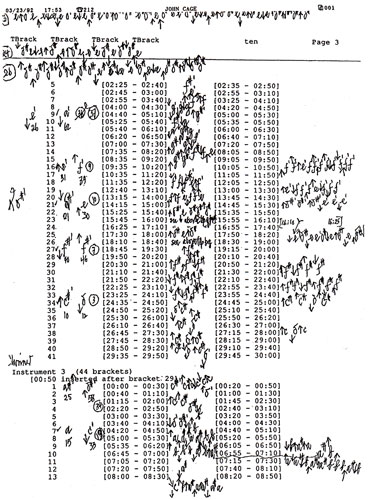

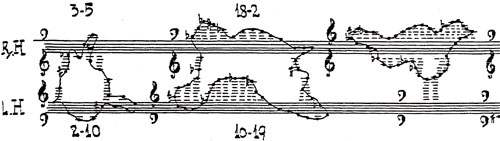

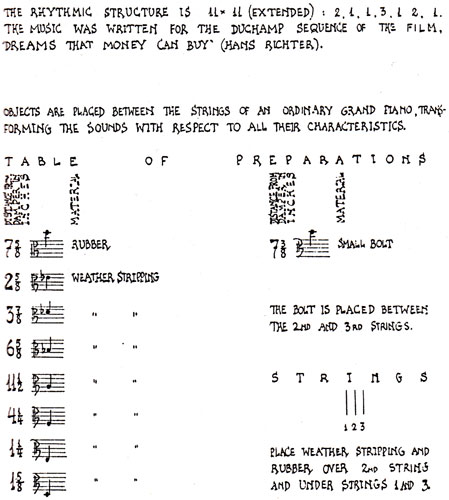

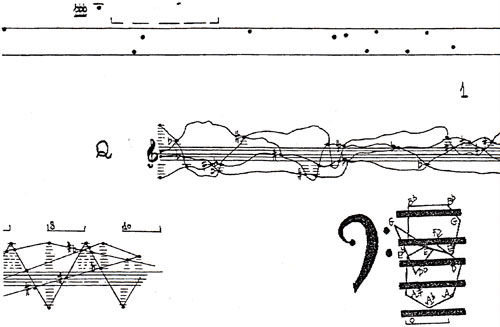

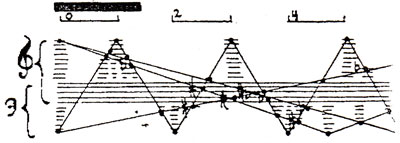

Scores by John Cage. Courtesy of Henmar Press, Inc. Photographs by Marion Ettlinger, 1992.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.