Thomas Cleary found the professor’s answer unsatisfactory, so he provided his own.

The tall, dignified student cut an interesting figure at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, where he earned a juris doctor in 2005. By then in his fifties, Cleary was already an accomplished scholar, having graduated with a doctorate from Harvard in 1975 and thereafter translating a stream of Asian classics, almost single-handedly filling the shelves of zendos and bookstores countrywide with the beginnings of a new Buddhist canon.

But by the early 2000s, the polymath had a different project in mind. The American legal system was in crisis, Cleary believed, and the arguments about how to improve it had grown stale, if not stagnant. He hoped to introduce new ideas from other cultures, just as he had done, a generation before, for spiritual seekers.

Sitting in the classroom one day, Cleary found a classmate’s question interesting and insightful. The professor’s answer, less so. So he researched the query, wrote a brief, and handed it to his surely surprised classmate, recalled Cleary’s longtime friend, Sartaz Aziz.

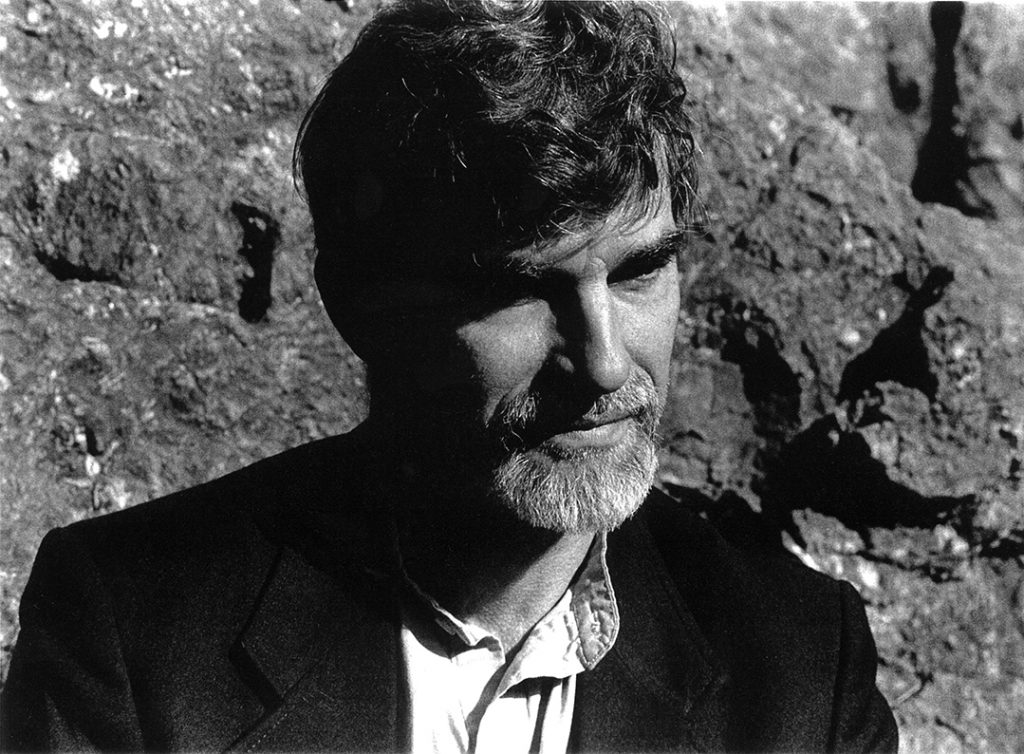

Cleary, who died in June at age 72 near his home in Oakland, was notoriously private. But if you want to know the man behind the nearly 90 books, this anecdote provides a skeleton key, his friends and family say. He was endlessly curious, concerned about big social problems, intimately attuned to the people around him, and studiously unimpressed by academia.

“Tom didn’t act like an intellectual hotshot,” said his brother, J.C. Cleary, with whom Cleary produced his first translation, in 1972, of The Blue Cliff Record. “He was the kind of guy you would find talking to the doorman, having an interesting conversation that had nothing to do with Buddhism or anything like that.”

Cleary may have been modest, but his accomplishments were not. In the wake of his unexpected death—the cause was complications from previous heart and lung ailments, according to his family—endless encomiums followed.

He was “one the greatest translators of our time,” said Nikko Odiseos, president of Shambhala Publications. Tibetan Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman credited Cleary with “almost single-handedly” building a Buddhist canon in English. The Soto priest Taigen Dan Leighton, who studied with Cleary in California, compared him to the fourth-century Indian monk Kumarijiva, who translated Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit to Chinese.

But Cleary’s books, which sold millions of copies, ranged far beyond Buddhism. He also translated works by Taoists, Greek philosophers, Celtic kings, and the Prophet Muhammad, including the Quran.

The last work caught the attention of Sheikh Hamza Yusuf, who had read Cleary’s Buddhist books and was surprised to learn the translator had also mastered Arabic. The two became friends and Yusuf, one of the world’s leading Muslim scholars, invited Cleary to teach at Zaytuna College, the school he co-founded in Berkeley.

“He was one of the most extraordinary human beings I have ever met,” Hanson said. “He described himself as a spy who was sneaking ideas across the borders of the mind.”

Cleary was born in 1949 in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where his parents were chemists. It was the Cold War, and the family paid the era’s requisite lip service to religion, but it was a largely secular household, recalled J.C. Cleary.

Born deaf in his right ear, Cleary caught grief from teachers who thought he was ignoring them, perhaps inspiring a lifelong distrust of academic authority. As teens, Cleary and his brother became interested in the Beatniks, Aldous Huxley, and Buddhism.

“I had non-ordinary experiences ever since childhood,” Cleary once told an interviewer, “and Buddhism put them into perspective.”

“He had a few moments where he caught glimpses of the oneness of things,” J.C. Cleary said.

The brothers began their first translations of Buddhist scriptures at 18, and Cleary matriculated to Harvard, where he studied Asian civilization, spending time in Japan. But the budding scholar eschewed academic debates and contemporary glosses, going directly to the scriptures themselves. Cleary explained his motivation in his introduction to Instant Zen:

As the practical relevance of ancient wisdom to modern problems becomes increasingly apparent, there is an ever greater need to retrieve these essential insights from ages of cultural overlay, embellishment and cultural decline.

Independent and determined, Cleary walked away from academia and moved to California, where he began his “spycraft” in earnest, focusing on texts not yet available in English and providing short but informative introductions to the worlds in which the works were created.

At the time, informed books about Buddhism were few and far between, with no internet to offer instant, global access to ancient texts. Cleary worked diligently—and often alone—to bring these works to readers in direct, unadorned prose.

Though he taught briefly at the California Institute of Integral Studies and San Francisco Zen Center, Cleary was skeptical of institutions, academic or religious, remembers his longtime friend Patricia Durham.

“Skeptical is maybe the nicest word you could use,” Durham said with a laugh. “He knew that, in those kinds of places, the best of intentions could often get lost.”

Cleary also avoided much of public life—skipping his publisher’s book parties, for example—but he was not a recluse, his friends and family say. He was deeply engaged with the world, preferring to teach through his books and during one-on-one seminars with a select group of students.

Durham, who met Cleary when her children took piano lessons from his wife, Kazuko, was one of those students. The mysterious figure who dutifully attended the children’s recitals recommended she read The Secret of the Golden Flower, and a friendship was born.

The recommendations continued, as did meetings every few weeks in which the two would discuss the books, which ranged from Buddhism to Sufi Islam.

“Because he was so scholarly, I anticipated he might be in some Ivory Tower or little niche,” Durham, an attorney, remembered. “But he was very attuned to what’s going on, to everything happening in the world.” Cleary and his wife helped Durham plan a school in Oakland and Cleary wrote newsletters on everything from Japanese business culture to Ebonics.

“He was most comfortable with children and living beings,” Durham said. “Cats and nature. Wild things.”

In the early 1990s, Cleary anticipated the rising tides of Islamophobia, which motivated him to translate the Quran, Islam’s most sacred text. He also sought out speaking engagements to educate his California neighbors about Islam, pointing out its connections and similarities with other faiths.

Sartaz Aziz, a Bengali-American writer, recalled meeting Cleary around that time. “I immediately saw a gentle, dignified, compassionate, and fascinating person. This first impression remained unchanged,” she said.

The two became writing partners, but more importantly, Aziz said, Cleary, who had no children of his own, became a surrogate father to her young daughter, helping with school projects and class presentations. Cleary learned Bengali so he could communicate with Aziz’s mother and translated a Bengali text, The Ecstasy of Enlightenment, dedicating it to her late father.

“Tom was engaged with life at all levels and in all forms,” Aziz said. “He believed that humans are essentially good, and their weakness and mistakes have been a result of being manipulated by a few people in power. He admired ordinary people who struggle to lead a decent life.”

Cleary was working until the end of his life. Next year, Shambhala will publish his translation of Dahui’s Treasury of the Eye of True Teaching.

After the publication of The Counsels of Cormac, in 2004, an interviewer asked about the commonalities he had found among the various cultures he had studied. His answer was characteristically short, pointed, and sage.

“Much could be said about this,” he said, “but to paraphrase Confucius, it seems our closeness is natural, our distance acquired.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.