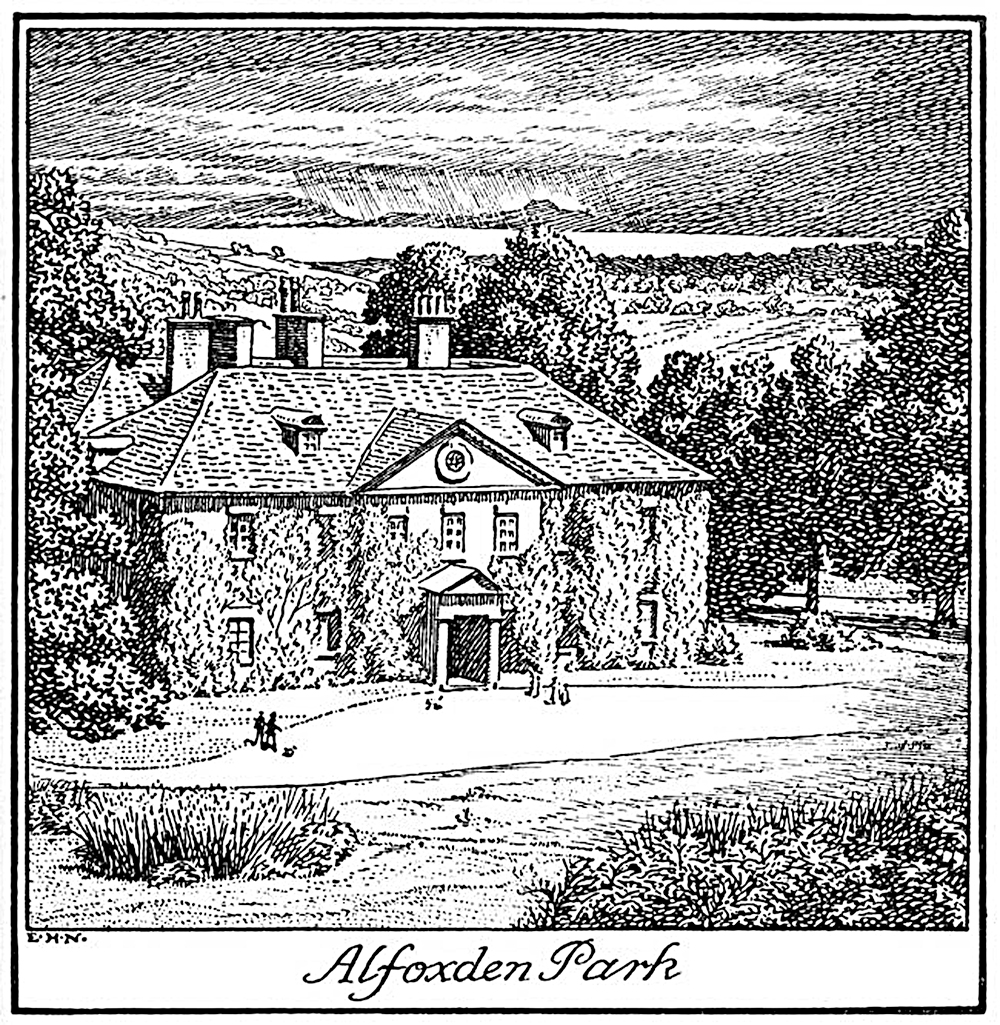

Alfoxton Park in Somerset, southwest England, sits halfway up a long incline that rises from the Bristol Channel to the Quantock Hills. The main house, built in a neoclassical style in 1710, could be home to a Jane Austen heroine. But look more closely and you see crumbling plasterwork, decaying windows, and a tumbledown roof. I’ve come to know Alfoxton since 2020, when it became home to a community of Buddhists from the Triratna Buddhist movement. Slowly, with great determination and few funds, they have been turning it into a retreat center devoted to meditation, sustainable living, and the arts. For now, the main house is uninhabitable, and community members live outdoors or in converted outbuildings and hold events outdoors under canvas coverings. Alfoxton’s allure comes from its ancient oak forests, where deer wander freely, and the drama of a dedicated band who, against the odds, are transforming a deteriorating mansion. But an episode in its history makes it unique.

For just over a year in 1797–1798, Alfoxton was home to the English poet William Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy. They came at the invitation of their friend, the poet and philosopher Samuel Coleridge, who lived nearby, and all year the three young people walked together and interacted intensively. Something remarkable happened among them. The two men wrote poetry and Lyrical Ballads, a collection they published jointly and is celebrated as one of the greatest volumes of poetry in the English language. It includes Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” and much else. Their preference for simple language and honest feeling over literary artifice forever changed the way poetry was written, and their valuation of beauty, imagination, and nature changed how art was understood. Along with their contemporary William Blake, they are remembered as the pioneers of English Romanticism, and their influence has suffused English and American literature.

Alfoxton’s significance is more than literary, especially for Buddhists like me. In their year there, Coleridge and the Wordsworths discovered a new kind of perception, and their greatest poems are explorations of consciousness and its many levels. They resonate with my own Buddhist spiritual life, not least because their experience is rendered through powerful symbols and with tremendous sensitivity to language. Some Buddhists of European descent are content to immerse themselves in the cultural expressions of Buddhist insight associated with Japanese Zen or Tibetan tantra. My own experience is that Western art speaks to me more directly. I know that its status has become problematic in multicultural societies and that mass popular culture is making it less familiar and therefore less accessible to readers. Nonetheless, I read Romantic poetry for its power, insight, and beauty, not for reasons of cultural elitism but because those qualities enrich my Buddhist practice.

I

n some quarters, “Buddhist Romanticism” has become a term of disparagement. The principal exponent of this view is Thānissaro—an American Theravada bhikkhu and a prolific scholar and translator. His 2015 book Buddhist Romanticism focuses on the German Romantic thinkers who, beginning in the 1790s, found new ways to understand art, society, and religion. Names like Schlegel and Schleiermacher may be little known today, but, Thānissaro says, their ideas became embedded in Western cultural conditioning when they were transmitted through movements like humanistic psychology. In turn, he believes these Romantic attitudes inform—and distort—how we understand Buddhism. They are “the framework into which Buddhist concepts have been placed, reshaping those concepts to Romantic ends.”

In Thānissaro’s view, Buddhist teachers who tell us to accept our experience with nonjudgmental receptivity, trust our feelings, or recognize our intrinsic goodness are really offering Romanticism in a Buddhist disguise. The Romantics he discusses saw religion as a quest to recognize “the infinite organic unity of the cosmos,” but he argues persuasively that this is a fundamentally different goal from the one set out in the Buddha’s teachings. For the Buddha, he says: “The ultimate cure involves going beyond feelings—and everything else with which one builds a sense of identity—to a direct realization of nibbana.”

For Buddhist practice to be effective, it must touch our hearts, not just our rational minds.

I recognize the importance of Thānissaro’s questions about the ways Buddhism is understood—and misunderstood—in modern culture. I agree with him about the importance of identifying our underlying beliefs and testing them against Buddhist teachings. I also agree that Romanticism is not Buddhism. But Thānissaro’s account of the “true path” relies almost exclusively on the teachings of Buddhism’s Pali canon, with no reference to the Mahayana and Vajrayana strands of the Buddhist tradition, let alone Western art, literature, or music. The result is that he rejects Romanticism as a whole, without distinguishing the English poets from the German thinkers and thereby excluding what for me are important sources of inspiration.

R

omanticism is best understood not as a philosophical position but as a response to certain trends in Western culture. In his classic study The Roots of Romanticism, Isaiah Berlin says the basic outlook of the European Enlightenment can be summed up in a few propositions: (1) all genuine questions can be answered; (2) these answers are knowable; (3) and they are consistent. The implication of this Enlightenment understanding is that the world can be fully comprehended through the exercise of reason. For Romantic artists and thinkers, this produces an unbalanced view of life that alienates us from sources of happiness and meaning within ourselves and the world we inhabit. Consequently, Romanticism, as Berlin and others present it, is a sprawling cultural tradition rather than a philosophical school, and its representatives offered many, often contradictory, alternatives to the mechanistic worldview they rejected.

For the sake of simplicity, I will take Coleridge and the Wordsworths, and their year at Alfoxton, to represent the wider movement. Like many in the generation that came of age in the wake of the French Revolution, Coleridge and the Wordsworths found mainstream Christianity hollow and conventional, and they chafed at the political repression in Britain during the Napoleonic wars. Both men began as political idealists, but when revolutionary France turned sour, they made an “inward turn” toward their own experience.

By the time of the Alfoxton year, Coleridge was already celebrated as a dazzling intellectual who was developing an antimechanistic philosophy out of German Romantic ideas and his own feeling for literature and religion. William Wordsworth was very different: a man of powerful emotions with an instinctive capacity to access the deepest levels of his experience. The feelings and impressions of his childhood in the Lake District, especially the “spots in time” in which he had felt a profound connection to nature, returned to him in moments of contemplation. Coleridge encouraged William to believe that his intuitive understanding contained important insights.

The third member of the trio, sometimes overshadowed by her companions, was Dorothy, whose attentiveness to immediate sensations and the physical environment grounded their grand reflections. Coleridge wrote that she was “watchful of the minutest observations of nature,” and her exquisitely observant notebooks are celebrated as accomplished literary works in their own right.

The embodied understanding that the Alfoxton trio valued—which Buddhists might associate with the practice of mindfulness—could be called a kind of philosophy, but it wasn’t a theory. As the cultural historian Iain McGilchrist writes, “For the Romantic mind theory was not something abstracted from experience and separate from it . . . but present in the act of perception.” They felt and believed that the world was more akin to a living organism than a machine, and that a healthy understanding was attuned to its aliveness.

Works of art offered an ideal way to express this organic, embodied understanding, and in the course of the Alfoxton year Coleridge composed a series of “conversation poems,” most famously “Frost at Midnight,” which presents thought as a liquid movement from observation to image to meaning and back again. William experimented all year with poetry that favored direct observation over artificial language and drawing room wit. Some poems described the people he met walking the Somerset lanes, intuiting wider forces through the minute particulars of their speech and appearance. Others celebrated what he learned through receptive awareness:

Think you, ’mid all this mighty sum

Of things forever speaking,

That nothing of itself will come

But we must still be seeking?

(“Expostulation and Reply”)

The wisest teacher of all was nature:

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

(“The Tables Turned”)

If these sentiments verge on cliché to modern ears, the reason is in part that Wordsworth has made them familiar. The least that can be said is that they are sincere, and their honesty opened the way to the great poetry of inner spiritual experience for which he is most remembered.

Dorothy and William left Alfoxton in the summer of 1798, moved to nearby Bristol, and embarked on a long walking tour of the Wye Valley, which runs along the border between England and Wales. As they walked, William composed a poem that he entitled “Tintern Abbey,” now widely celebrated as one of the greatest poems in English, which expresses everything he’d learned at Alfoxton. He reflects that the memory of this place has sustained him in the five years since he had last visited. They had inspired “little, nameless, unremembered, acts / Of kindness and of love” and prompted experiences of profound meditative absorption:

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

The pattern of experience Wordsworth describes is recognizable to anyone who is familiar with the Buddhist threefold way, according to which ethical action is the basis of meditation, and the experience of absorption prepares the way for insight.

Both Coleridge and Wordsworth held that the deepest truths are discovered within the realm of consciousness—another truth whose familiarity we owe to them (though not, of course, to them alone). They believed it connected them to something beyond their personal psychology, and the central passage in “Tintern Abbey” is the poet’s account of the presence he feels when he engages deeply with nature:

a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

What does Wordsworth mean when he speaks of a motion and spirit that is interfused with the ocean and sunset? Is it God in nature, or is he elevating nature into a kind of God? I prefer to approach the lines as the communication of an intuitive rather than a quasi-religious belief. They remind me of my own experience beneath the stars and in meditation, when the natural world seems indivisible from my mind and reality unfolds without my conscious willing.

Buddhist contemplatives have often described moments of inspiration in nature—from the verses of the Buddha’s disciples recorded in the Theragatha to the mountain poetry of Chan and Zen masters. Wordsworth’s poetry belongs within that tradition as well as within English literature, and it is particularly important to me because it is rendered with an unforgettable imaginative power in my native tongue. Where he counsels “Let Nature be your teacher,” the monks of the Theragatha balance their enjoyment of nature with an awareness that its beauty can be a distraction. But, despite a tendency in Theravada tradition to disparage nature, delight and detachment coexist harmoniously in the experience of monks like Bhuta Thera:

When along the rivers the tumbling flowers bloom

In winding wreaths adorned with verdant color,

Seated on the bank, glad-minded, he meditates.

—No greater contentment than this can be found.

(trans. Andrew Olendzki)

A

long with the conversation poems, in the Alfoxton year Coleridge wrote a set of mythic, or “daemonic,” poems that include the “Ancient Mariner,” “Christabel,” and the visionary fragment “Kubla Khan,” with its famous opening:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

These few lines take the reader through a symbolic landscape. A sacred channel runs from the open air toward a vast underground cavern that is buried in darkness. The poem invites us not just to visualize the scene but also to sense what it symbolizes. To me it speaks of subconscious forces seething beneath the surface of experience—a Romantic reflection that psychoanalysis made familiar. The poem’s meaning unfolds through symbols, and Coleridge believed that symbolic thinking and the faculty of imagination enable us to intuit realities beyond our current experience. He wrote some years later, in his chaotic tract “Biographia Literaria”:

They and only they can acquire the philosophic imagination, the sacred power of self-intuition, who within themselves can interpret and understand the symbol, that the wings of the air-sylph are forming within the skin of the caterpillar.

To contemplate, or imagine, a symbol, Coleridge suggests, is to sense our butterfly wings when we are only caterpillars. A central practice in Mahayana and especially Vajrayana Buddhism is visualizing images or chanting mantras and allowing their meaning to unfold in our experience. Even in the early texts we find disciples such as Pingiya testifying that they keep the Buddha in mind—or imagine him—with “faith, rapture, thought, and awareness.” The imagination, as explained by Coleridge and his contemporary William Blake, helps me make sense of Buddhist practice by redirecting my awareness from ideas and sensations to a form of cognition that combines thought, feeling, and intuition. I don’t assume this is precisely what Buddhism means by faith or wisdom, but it makes them more comprehensible to me.

The concerns of the Romantic poets remain relevant. If we recoil from a view of the natural world as a lifeless resource and yearn for an alternative, we recognize the challenge the Romantics addressed. If we feel the importance of intuition and imagination, we inherit the Romantic model of experience. If we regard myths and symbols as routes to understanding, we participate in the Romantic sensibility. For Buddhist practice to be effective, it must touch our hearts, not just our rational minds. Romantic poetry often expresses insights akin to those of Buddhism with intense feeling and in gloriously resonant language.

I feel this resonance at Alfoxton when I walk through the forest where Dorothy described the trees “showing the light through the thin net-work of their upper boughs,” and in the garden where William wrote a note in verse urging:

With speed put on your woodland dress;

And bring no book: for this one day

We’ll give to idleness.

(“To My Sister”)

I think of it when I see the inspired, mostly penniless, community, working for the sake of the land, friendship, the dharma, and the shimmering prospect of what Alfoxton might yet become.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.