Excerpted from the second video of Tricycle Meditation Month 2026: “Awakening with Zen Koans.”

Koan: What was our true face, our original face, before our parents gave birth to us?

This koan is a call to peel off any kind of accumulated identities or preconceived ideas about ourselves: label, name, or anything. It is asking us to see if we can free ourselves from all of [these labels] and return to a state of wonder—to the childlike curiosity and joy.

In Buddhism, we want to arrive at unconditional freedom, and anything that is conditional, even if it looks really good, is ultimately going to bind us, or imprison us.

A good example would be somebody who defined themselves as being kind. “I’m a very kind person.” Yet sometimes you run into a situation where it is impossible to be kind. For example, somebody walks up to you and threatens the safety of you or your child or your dog. Could you be true to your kind nature? If you say, “I have to be kind because that’s who I am,” then you could become a victim of crime.

In other words, whatever we identify ourselves with—whether it is personality, memories, or identities—they also become our prison. Therefore, this koan is asking us to free ourselves, even momentarily.

Also, this koan is a call to our pure awareness prior to all of those ideas and identities.

***

When we first learn Buddhism, we study that there is no self: selfless nature. Because we analyze that, what we consider to be self is nothing but five aggregates, or the five skandhas. They are our body, emotions, feelings, thoughts, volition, and consciousness. When you examine [the self], what’s really there? There is nothing but the five aggregates, or the five skandhas.

But, in truth, all those aggregates—whether it’s your body, feelings, thoughts, volition, or consciousness—are objects. They can be observed. You can perceive them, rising and disappearing. We can perceive our body, too, which means it’s not the subject, because the subject is perceiving or observing. Then what is it that is knowing all of this?

Rather than reducing ourselves to be a mere object, such as our body, feelings, and thoughts, what is that which is observing? That which is knowing? That’s the question.

***

I can observe my body, and I can observe the rising and disappearing of my thoughts. I can also observe how my emotions change—sometimes happy, sometimes unpleasant. However you define yourself or your consciousness, you’re drawing boundaries. “This much is my consciousness.” And you are quickly turning whatever that experience is into an object.

So when you perceive an object, what happens? Instantly, it creates a dualistic existence. I, as an observer, observing the object. However, this koan is basically saying, “Hey, all those things that you have accumulated—labels, names, personality, memory, identities—they are all objects.” So it is calling you to come back: “Come back to your original nature before the subject-object split.”

***

I remember when I was 10 years old and I was in Korea learning English for the first time, for the longest time I thought apple was called sagwa (사과). In Korean, it’s called sagwa (사과). Then my teacher said, “No, in English, it is apple.” Then I realized, “Oh, the word 사과 is just like apple. It is man-made.” We created this artificial word to communicate. But because we are so used to it, we forget that it is artificial. It is something that we accumulated or created later on.

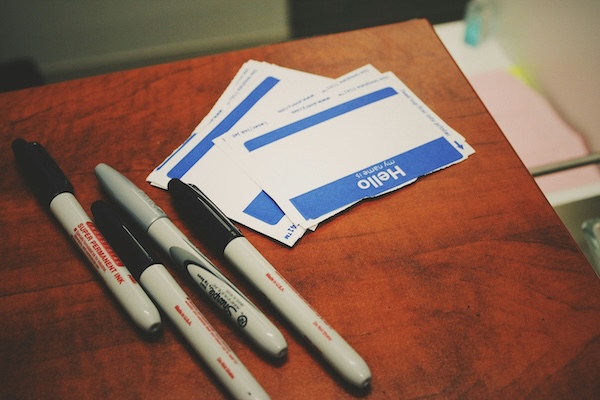

If you really think about it, the idea of having a name is also strange. When you were just born, you didn’t have any name. And somehow, because you had to communicate, your parents or your caregiver decided to call you whatever: Peter or Jennifer or Tom or whatever. How strange is that?

Your true nature is nameless, defineless. So when we can let go of whatever the identity is that we are holding on to, there is freedom—a state of unconditional freedom.