On July 12, 2025, during UNESCO’s 47th session of the World Heritage Committee in Paris, a stretch of forested land east of Hanoi dotted with ancient Buddhist structures called the Yen Tu-Vinh Nghiem-Con Son, Kiep Bac Complex of Monuments and Landscapes was officially recognized as a World Cultural Heritage Site. The chain of sites originates at the peak of the Yen Tu Mountain, where a thick grove of bamboo manages to hide a sprawling monastery complex called the Hoa Yen Pagoda, first constructed in the 11th century by the Ly dynasty. Beyond the ancient grounds and the stone walls slicked with lime-green lichen, through a winding path braced by twisted nets of leaves and branches, down a flight of stone steps into a narrow ravine, you will find a complex housing a towering golden statue of a simple and unassuming monk. Robes slung over one shoulder, he sits peacefully in meditation posture with a gentle yet subtle smile on his face—the locals call him the Buddha of Vietnam.

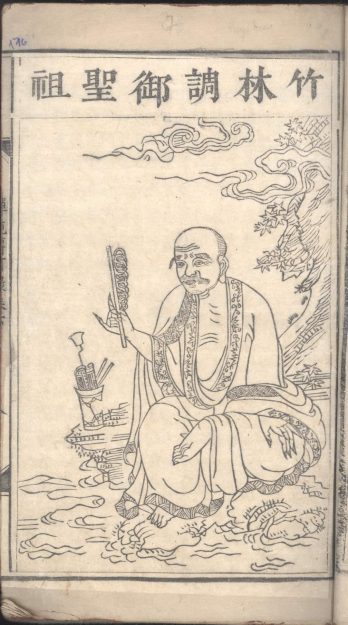

World history recalls him as Emperor Tran Nhan Tong (1258–1308 CE), the third monarch of the Tran dynasty. As emperor, he successfully led the nation twice against Mongol invaders. As a monk, he founded the first distinctively Vietnamese school of Thien, naming it Truc Lam (“Bamboo Forest”), and developed a new philosophical tradition encouraging the cultivation of the bodhisattva path through sociopolitical engagement he called Phat giao nhap the (literally, the “Buddhism that enters the world”). This newly recognized World Cultural Heritage Site is a historical monument to the accomplishments of his life and his contributions to Buddhism, as the emperor ferried Dai Viet to the absolute zenith of what is considered the Buddhist Golden Age in Vietnamese history.

Born with the name Tran Kham, he had hoped to shirk the responsibilities of his ensuing coronation by absconding in secret to Hoa Yen Pagoda to request monastic ordination from the temple’s abbot when he was 16. The citizens of Dai Viet would have awakened to this news that morning feeling it to be quite familiar, as Nhan Tong’s grandfather—the Awakened-Emperor Tran Thai Tong, most well-known today for authoring the meditation and repentance text called Instructions on Emptiness (Vn: Khoa Hu Luc)—had tried to pull the exact same stunt forty years earlier! And just as his grandfather had been turned away, so, too, was the young prince, who reluctantly returned to the palace to take the throne and fulfill the civic duty demanded of him by birth. But politics was not his passion, and he could do nothing to satiate his thirst for the dharma. Nhan Tong spent whatever time he could muster reading scriptures and practicing meditation, squeezing in brief moments of sitting or study between his stately duties. However, his political education required a deep study of Confucianism, the school of thought governing the culture of secular and social ethics of the time, which stole time away from his study and practice of the buddhadharma. Young Nhan Tong could feel bitterness brewing deep in his belly; he knew he had to find a way to bring the joyfulness he experienced studying the Buddha’s teachings into his life as a politician, and, as such, he began contemplating how he might integrate Confucian secular ethics into his dharma practice. While this project of harmonizing the Buddhist path of renunciation with the Confucian path of social engagement would become Emperor Nhan Tong’s primary concern for most of his life, before he could focus on the buddhadharma and on his real passion—philosophy—he was duty bound to focus on the more pressing and dreadful matters of politics and military strategy, as Dai Viet was being invaded.

*

The Mongols tried to invade once before, during the reign of Emperor Thai Tong, and were summarily defeated in 1258. The young Nhan Tong had grown up hearing stories about how his grandfather had emerged victorious over the Mongol horde. Kublai Khan had recently assumed power over the Mongol Empire in the far north of Asia, and his eyes were set firmly on seizing Song dynasty China. First, the Mongols took Liao and the Western Xia, then Manchuria. Next, they annexed Tibet as well as the Dali kingdom (modern Yunnan province, China). If the Mongol Empire were to have been able to secure Dai Viet, too, it would have had the Song entirely surrounded, and then taking the whole of the Song territory would have been trivial. But Emperor Thai Tong successfully fended off the invaders after enduring a yearlong siege of Dai Viet’s capital, Thang Long, leaving the Mongol Empire to move on to other strategies toward conquering China.

Kublai Khan had, in fact, not needed Dai Viet at all, instead relying on advanced counterweight trebuchets to lay siege to Xiangyang—a strategy that Marco Polo took credit for in his travelogue but which historians firmly credit to Persian engineers who were envoys to the Khan. Nearly thirty years later, the Song dynasty was now decimated. In its place, Kublai Khan established a new dynasty he called the Yuan, and now commanded the united force of the massive Mongol horde and the most powerful, wealthy, and technologically advanced military on the planet. His infantry firmly established, Kublai Khan set his eyes on Dai Viet again. This time, the goal was not to secure an advantage over China—China was already his. No, Kublai Khan sought Dai Viet for the sake of it, because he had designs on the entire world, and this little nation on the Red River Delta somehow had the audacity to have eluded his possession. In 1278, at the age of 20, Nhan Tong was crowned emperor. Kublai Khan used this occasion to send an envoy to him, demanding subservience, which the young emperor dismissed. Kublai Khan made several more attempts to broker an audience with Nhan Tong, all of which were ignored.

Finally, in 1284, Kublai Khan sent his son Toghon with a military force overland to Thang Long, demanding Dai Viet’s cooperation in an attack on the kingdom of Champa to the south. Following the advice of his father, Emperor Emeritus Thanh Tong, the young Nhan Tong refused to cooperate, leading to an enraged response by Toghon, who immediately advanced his infantry toward Thang Long, beginning the second Mongol invasion of Dai Viet. In an interesting historical footnote, it is generally accepted that Marco Polo accompanied Toghon on his expedition while he was en route to Burma, and wrote of Dai Viet under the name “Caugigu” (likely a corruption of the endonym for ancient Vietnam, Giao-chi). Marco Polo described the Vietnamese people as “idolators” and appeared fascinated by the tattoos of lions, dragons, and birds that universally adorned Vietnamese people’s bodies. The Tran dynastic court legally required all nobles to be tattooed by age 16, and tattoo designs were tightly regulated by social status. This entire legal framework would be repealed two decades or so later, as Emperor Nhan Tong’s son—the future Emperor Tran Anh Tong—was so deathly afraid of needles he overturned the laws at the very moment of his coronation and refused to ink his body, which resulted in the practice fading from popularity within just a couple of generations. At this time, though, with Toghon’s army marching on Thang Long, Tran dynasty soldiers took to tattooing the characters “殺韃” on their hands and faces—“Sat That ” in Vietnamese, or, “Kill the Mongols.”

In February of 1285, Toghon’s forces had succeeded in capturing Thang Long. Vietnamese forces started many skirmishes with the Mongol army on their approach but would quickly retreat soon after. When the Mongols finally were able to burst through the gates of Thang Long, they found the metropolis and even the palace completely deserted—the earlier battles had been diversions, the Vietnamese buying time to safely abandon the capital. As Dai Viet’s population emptied out of the city, the military destroyed any major infrastructure that might be useful in their wake—major roadways were torn up, bridges were collapsed, farmland was razed or flooded, and all the city’s well water was contaminated with dead rats. Vietnamese aristocrats and commoners alike had retreated into the mountainous jungles. Drafting themselves into makeshift militias, they began employing hit-and-run tactics on Mongol supply routes and booby-trapping the canal networks branching out of the Red River so that any Yuan supply vessels would be shipwrecked and easily pillaged.

Even in the midst of this war, Emperor Nhan Tong was preoccupied with reflections on the dharma. He wondered, how could he be a good king to his people during this time of war and be a good Buddhist as well? Though the violent messaging tattooed on the brows of his loyal soldiers might have suggested otherwise, Nhan Tong was obsessively strategizing to minimize the loss of life on both sides. His forces were massively outnumbered by the Yuan forces, his army technologically inferior. There was no chance of winning a direct confrontation against the combined might of the Mongol cavalry and Chinese gunpowder. As the months stretched on, high-ranking senior mandarins in the Tran court began defecting to the Yuan. But Emperor Nhan Tong assured those who remained to keep their faith in victory—the monsoon was only a short time away, and every day, the weather grew warmer and the Yuan army grew hungrier and sicker. By May, Nhan Tong’s conviction was vindicated. By then, it was becoming quite apparent that the Yuan supply network was overextended and the occupation of Thang Long could not be sustained much longer. The rainy season had arrived slowly, rains starting and stopping in sputters, but had soaked the earth in just enough moisture that clouds of mosquitoes emerged hovering over every puddle, billowing skyward out of the city’s wells like thick streams of chimney smoke. A pestilence of malaria swept through the weak, hungry Yuan forces. And then, in early June, Emperor Nhan Tong amassed a force to retake Thang Long. As the Vietnamese marched toward their capital city, they took care to make a great demonstration of their health and vigor in the heat and humidity of the summer rainy season, appearing and disappearing amongst the trees and bushes and mountainous rocks and caves surrounding the city, terrorizing Toghon’s soldiers from every direction. Additionally, the mud entirely defanged the advantage of the Mongol cavalry, acting like glue traps on the horses. Toghon realized quickly he could not hold Dai Viet. Embarrassed and embittered, he reluctantly ordered a full retreat. The occupation had lasted for only six months.

Toghon was not yet done with Dai Viet, but it would take two more years for the third Mongol invasion to commence. In that time, the Yuan forces devised a new strategy: Toghon would lead an overland infantry of nearly 150,000 soldiers to conquer the capital; at the same time, Admirals Omar and Fan Yi of the Yuan navy would lead an additional 18,000 soldiers, who were spread across a fleet of 500 ships, to secure a supply route by sea up the Bach Dang River to Thang Long. They were sure of victory this time, set on overwhelming the Vietnamese by sheer numbers and military might from land above and sea below.

But Dai Viet had also spent the last two years plotting contingencies for the Mongols’ inevitable return. With the counsel of his uncle, Grand Prince Hung Dao, Emperor Tran Nhan Tong settled on an ingenious strategy he was certain would minimize casualties on both sides. When Toghon’s gargantuan army arrived at Thang Long, it once again found the city deserted. This time, Nhan Tong did not retreat into the jungle but boarded a ship with Prince Hung Dao and sailed out to sea with a small fleet. As they left, they lit the palace ablaze and Toghon’s army found only smoldering ash and black smoke where it once stood.

Emperor Nhan Tong took measures to prevent Toghon from occupying Thang Long for another six months. When Toghon’s forces opened the city’s granaries, they were discovered to have been completely emptied, the Vietnamese having loaded all the grain onto ships in the weeks prior to be hidden in secret storage facilities spread out amongst the scattering of small islands across the South China Sea. The Mongols had depleted their provisions on the march southward—there was no food with which to replenish their stock. And, unbeknownst to Toghon, the supply fleet that had been tailing his army and that was supposed to arrive in Thang Long within days had already been attacked by thirty warships in the previous week and was forced to retreat to the island of Hainan. After a fortnight of holding the capital uncontested, Toghon realized that his main support and supply routes had been cut off. If Admiral Omar’s massive naval fleet coming up from the south didn’t arrive soon, the Mongol army would have to retreat.

Grand Prince Hung Dao had predicted Admiral Omar’s route would take the Bach Dang River, however, and had ordered his men in the early part of winter to deploy a carpeting of steel-tipped wooden stakes on the riverbed, invisible during the high tide. Together, Prince Hung Dao and Emperor Nhan Tong led a fleet of smaller vessels, significantly more agile than the Yuan warships, and lured Admiral Omar’s fleet into the Bach Dang River during high tide, ensuring the enemy ships were positioned right atop the booby-trapped sections of riverbed. As the tide began to recede, the smaller Vietnamese vessels swiftly circled around the Yuan fleet, gathering in formation at the mouth of the river, blocking any escape. When the river’s waters drained back into the ocean, the Yuan warships became stuck on the steel-tipped stakes, unable to turn. Eventually, the tide receded so much and the weight of the warships was so tremendous that their hulls gave way to the steel of the stakes and the ships began to sink. The entire Yuan fleet was destroyed, while Vietnamese infantry awaited along both sides of the rivers to capture troops attempting to swim to safety. When news of this humiliating defeat reached Toghon, he quickly gathered his forces and retreated northward to China for the final time.

For those practitioners across the globe who see themselves aligned with Engaged Buddhism, to know this history is to be grounded in a centuries-old heritage.

Emperor Nhan Tong returned to the capital victorious and relieved. He had done it: He won a defensive war against the most powerful and technologically advanced military force on the planet, humiliating them so thoroughly that they surely would not dare invade again, and he had done so in a way that minimized battles, bloodshed, and loss of life. He had always loathed all the ways being a ruler forced him to take actions that conflicted with the buddhadharma, but now—in the inspiring afterglow of this triumph—he was more certain than ever that there was a way to cultivate the bodhisattva path through one’s duties to state and society as outlined in Confucian doctrine, and that a skillful fusion of Buddhism and Confucianism put into practice would result in secular and spiritual prosperity for all. He resolved to set his mind toward contemplating this philosophical project—a unified, nonsectarian Buddhism that enters the secular sociopolitical world and engages it with mindful compassion.

*

As the nation rebuilt, Emperor Tran Nhan Tong lost himself in worry. Confucian duty permitted him to return prisoners captured from the Yuan army safely to China but also compelled him to execute the defectors—even the members of his own family. This was a thought the emperor could not stomach. He wondered what a wheel-turning monarch would do in his place. If there were such a ruler, a monarch who might otherwise be a Buddha if their role in the world were not to rule, surely, they would not even think to execute anyone within their realm. And so Tran Nhan Tong thought hard and found a path to amnesty. For every member of the court that had defected, their family name was officially changed from Tran to Mai, losing their aristocratic privileges under the Tran dynasty. Next, the emperor issued an order that all military service records were to be burned, so that among the soldiers and commoners, it would not be possible to determine if someone fought for the Yuan or for Dai Viet. In this way, all defectors were pardoned.

But there was still the matter of reconstruction. The remains of the palace had to be cleared and entirely rebuilt. Sabotaged fields needed to be tilled over and made fertile farmland again. The bridges and roads that had been destroyed needed to be repaired or replaced as well. But all this rubble represented an incredible opportunity for Emperor Nhan Tong: He could refine his thoughts on how a bodhisattva most effectively practices the dharma as a householder and test what a Buddhism that enters and engages the secular world might look like.

At this time, Dai Viet was still a nascent nation—its independence from China was won just scarcely three centuries prior. The Chinese occupation had totaled over a thousand years and Chinese culture had been forced upon the Kinh people to such a degree that the architecture of the courts, palaces, administrative buildings, monasteries, and temples were all Chinese—the brackets that held the support beams were Chinese; the tiling for roofs was of Chinese design; the layout of the Imperial Court was configured under the principles of Chinese geomancy, which contradicted principles of Vietnamese geomancy. The Imperial Court had been built oriented on a north-south axis, aligning with the cosmic order of Heaven under Chinese geomancy—this strict adherence to Chinese conceptions of celestial order would have, to the medieval Vietnamese eye, depowered local ancestral and animist gods, subordinating them to the gods of the Chinese Heavenly Court. When Nhan Tong had the palace rebuilt, he ensured the architecture style reflected local Vietnamese style, oriented on an axis that aligned with sites venerating local mountain gods and the water spirits of the Red River Delta, in effect de-Sinicizing the imperial court and reempowering the deified ancestors of the Vietnamese people.

Even in language, all state and religious documents were recorded, maintained, and transmitted in the Chinese language and Chinese characters, called Chu Han. The Vietnamese had their own script and language, illegible to the Chinese, called Chu Nom, which up until this period had been confined to usage in Vietnamese folk poetry of low literary status. Emperor Nhan Tong saw how the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people had been so thoroughly colonized, that even they looked down on their own language, believing the Chinese language did, indeed, have some special, mystical, and artistic esteem. He could benefit the people best, and build the causes and conditions that would ferry them to the buddhadharma, if he focused his efforts on the decolonization of Dai Viet.

Nhan Tong’s work was swift. He immediately declared all state documents to be recorded and maintained in Chu Nom going forward. He did the same for religious documents. He composed and published a number of poetry collections in Chu Nom, elevating the prestige of Vietnamese literature from its folksy reputation into the realm of refined art and spurring a lively new dharma poetry movement among the educated aristocracy. Lords and ladies alike would gather together in candlelit tea houses in the evenings, sharing and appreciating art with one another, sipping at warm cups of green tea as they enjoyed dance performances meant to evoke Avalokiteshvara through their movement, and read the poems they’d composed to one another, hoping to demonstrate the depths of their dharma insights in friendly competition—the poetry slams of the Buddhist middle ages.

Next, using the wealth seized from the defectors to fund his reconstruction efforts, Nhan Tong built out a network of Buddhist monasteries, shrines, and learning centers emanating westward from the Hoa Yen Pagoda on Yen Tu Mountain and weaving a path through the mountains back to Thang Long. In the province of Quang Ninh, in the valley of the mountain at the forest’s edge, the emperor funded the construction of a retreat center called Ngoa Van Hermitage, as an addition to Vinh Nghiem Pagoda, where he would stay during the wet seasons to study the dharma and practice meditation. The emperor encouraged all the nobles in Dai Viet to not only study and practice the buddhadharma but also to donate their wealth to fund the expansion of more Buddhist learning centers. A stele at Vinh Nghiem describes how all the noblemen of the nation, inspired by Tran Nhan Tong’s self-funding of Ngoa Van Hermitage, began collectively buying up chunks of the surrounding pine forest to donate to the temple complex, in order to offer the buddhadharma to the Vietnamese people well into the future.

Not far from Vinh Nghiem, just down a dirt road, there was another temple called Quynh Lam Pagoda, first constructed during the Ly dynasty, which the emperor began renovating and expanding upon next. An institute dedicated to the study and practice of the Thien school was added to this temple. Not long afterward, a new building was constructed at Quynh Lam Pagoda, housing a printing press facility and libraries of texts in woodblock prints, in order to publish and propagate Buddhist scriptures exclusively printed in Chu Nom and the Vietnamese language for the first time. And with scriptures now available in Vietnamese, in a script the aristocracy was able to read, the gentry of Dai Viet found themselves hungry for deeper study of the buddhadharma. Within a few years, the Quynh Lam site developed into a thriving Buddhist university—the first such institute in Vietnamese history—a sprawling campus stretching over a thousand square acres, hidden in a thick growth of pines at the edge of Yen Tu Forest.

The emperor spent five years in the postwar period leading the nation through its reconstruction, building up and nurturing a thriving peacetime Buddhist culture, before he abdicated the throne in 1293 and had his son crowned as Emperor Tran Anh Tong. Finally retired from politics, Nhan Tong was now free to fulfill his dream—he shaved his head and donned the triple robe, intent to focus the remainder of his life to promulgating Buddhism. He went to his retreat center at Ngoa Van, studying scriptures intensively and practicing meditation. He spent several years in seclusion, eventually receiving transmission of the lamp from all three of the Thien lineages present in Dai Viet at this time: the Prajnaparamita-focused Vinataruci lineage; the lay-oriented Vo Ngon Thong lineage; and the Thao Duong lineage, a Pure Land Dual Cultivation tradition descending from the Yunmen school of Chan. In 1298, he emerged from retreat, publishing a commentary-in-verse called the Rhapsody of Engaging the World, Joyful in the Way (Vn: Cu Tran Lac Dao Phu). A philosophical treatise composed in ten cantos, the text presents a unified and systematic approach to the Thien, Pure Land, and Esoteric schools of Buddhism, while simultaneously reframing and interfusing them with concepts from Confucianism, Taoism, and Vietnamese folk religion. Through this monumental work, Thien Master Tran Nhan Tong established a wholly new philosophical tradition, giving it the name Phat Giao Nhap The, the Buddhism that enters into and engages with the secular world. This philosophy became the backbone and identifying characteristic of the unified school of Thien he founded. This became the national religion of Dai Viet, imbued with a distinctively Vietnamese character and absorbing all other Buddhist traditions. Founding this new Thien school, the first Buddhist meditation lineage indigenous to the Vietnamese, was the retired emperor’s last grand act of decolonizing Dai Viet from Chinese influence. Nhan Tong called this Thien school Truc Lam (“Bamboo Forest”), named for the ancient bamboo grove at the peak of Yen Tu where Hoa Yen Pagoda had been built.

The retired emperor turned monk quickly recruited platoons of disciples. With Hoa Yen Pagoda serving as the root monastery up on the peak of Mount Yen Tu, the Vinh Nghiem complex as a retreat center, and Quynh Lam operating as a Buddhist university and printing press, the imperial Thien master found himself in need of a new location dedicated to instructing monastics and lay followers alike in the theory and practice of the Truc Lam school. He found this at the foot of Con Son Mountain, at the edge of the province of Hai Duong, where Master Nhan Tong and his disciples established two new facilities about five kilometers apart from each other—the first was called Con Son Pagoda and became the training facility for the Truc Lam school. The other was named Kiep Bac Temple, built on a military training site Grand Prince Hung Dao had used during the wartime period to prepare the Dai Viet army and renovated and repurposed it into an ancestral temple. The grand prince passed away in August of 1300 CE and was buried at a small hill beside Kiep Bac Temple. Emperor Emeritus Nhan Tong had shrines erected for the grand prince and his family, and the families of all the soldiers that had served under him, at the temple, incorporating Vietnamese folk ancestor worship practices into the duties of Thien monks.

Now, with the three complexes drawing a line eastward from Thang Long to the peak of Mount Yen Tu, containing lively communities of practitioners meditating, studying, and translating scriptures, the Truc Lam school ferried Vietnam’s Buddhist Golden Age to its absolute zenith. Nhan Tong rooted the Truc Lam school in his philosophy of engaging the world. He encouraged the masses to practice repentance, chant the Buddha’s name, and practice the ten wholesome actions. He encouraged the aristocracy to fund the building of stupas, bridges, piers, and temples, calling these acts of social philanthropy the “external adornments of a bodhisattva” in his Rhapsody of Engaging the World, Joyful in the Way, while still emphasizing traditional practices of meditation, mindfulness, cultivating compassion and loving-kindness, and purifying the mind as a bodhisattva’s “internal adornments.” There is a story that takes place after Con Son Pagoda’s construction was completed where Thien Master Nhan Tong, troubled over the scale of destruction that had taken a toll on the natural environment during the war, gathered together his monastic and lay disciples to toil alongside one another in the dirt and soil along the path from Con Son all the way up Mount Yen Tu to Hoa Yen Pagoda, planting rows and rows of an indigenous species of red pine tree known as the arhat pine.

Tran Nhan Tong, drawing from his experience of having to reconcile his burning desire for monasticism with his secular duty to his nation, made the case that each person has the ability to achieve full awakening, using the conditions that they are born into—whether that be as a king, a minister, a soldier, a merchant, a laborer—there was no need to escape one’s conditions. The practice of liberation can be undertaken in the here and now, because all beings are endowed with buddha-nature, and a purified mind cannot be defiled by the sensory world.

Tran Nhan Tong passed into parinirvana in December of 1308 at the age of 50 and was posthumously given the title Buddha-Emperor (Vn: Phat Hoang). Tradition states that his dharma heir, Ancestor-Master Phap Loa, recovered 3,000 jeweled relics from his cremated ashes, which are today distributed across eight sites along the path that connects the Yen Tu-Vinh Nghiem-Con Son, Kiep Bac Complex together, with the bulk of the relics enshrined in the Ancestral Hall of Quynh Lam Pagoda as a field of merit for Vietnamese lay devotees to worship. The recent recognition of the entire complex by UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee is an incredibly proud moment for Vietnamese Buddhists. The legacy and impact of Buddha-Emperor Tran Nhan Tong’s teachings on Vietnamese Buddhism today and over its history of development since the 13th century cannot be understated. Engaged Buddhism has become a worldwide phenomenon, and yet the history of Tran Nhan Tong’s role in the tradition’s origins and development is little known outside Vietnam. But for those practitioners across the globe who see themselves aligned with Engaged Buddhism, to know this history is to be grounded in a centuries-old heritage, to a lineage firmly rooted in a red pine forest east of Hanoi, and to be empowered by it. There, in a bamboo grove, a monk that was once emperor attained awakening and showed the world through both words and deeds how to interfuse sociopolitical activism and altruism with spiritual praxis, for the sake of liberating all beings.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.