When I moved to Japan, I became enamored of the life and work of the fascinating Buddhist nun Otagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875). She was a martial artist, go player, poet, calligrapher, painter, and potter. Her life was marred by one tragedy after the other.

By the time she was 42, Rengetsu had suffered the loss of two husbands, all her children (at least four), her five brothers, and her parents. After the death of her second husband, at age 33, she took monastic vows assuming the name Rengetsu, meaning “Lotus Moon.” When her father died nine years later, Rengetsu settled on pottery making, incising the pieces with her original poems, to make a living. Rengetsu’s unadorned, unpretentious pottery turned out to be hugely popular, and pottery making became Rengetsu’s primary means of support. She also brushed thousands of pieces of calligraphy and paintings to raise money for charity. In her lifetime, Rengetsu was known as the “woman too beautiful to believe” for her good looks and the “Bodhisattva Nun” for her good works. In her lifetime, she is believed to have created more than 100,000 pieces of art across different media. Rengetsu died peacefully at the age of 85 in the tea room of Jinko-in Temple in Kyoto. Pretty soon into my relocation to Japan, I began collecting both her pottery and brushwork. Her scrolls were hung around my home, and I used her pottery in my daily life. She became my teacher, my friend, and, finally, my healer.

In 2020, the Monestir de Pedralbes, a magical 14th-century Poor Clare monastery in Barcelona, Spain, sponsored the exhibition The Lotus Moon: Art and Poetry of the Buddhist Nun Otagaki Rengetsu. The Catholic sisters had turned one of the church halls into a museum, and wanted to feature outstanding female religious figures of different traditions from around the world. The first exhibition was for Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943), a German-Jewish artist whose prolific and musical gouache works belie a life cut short by Nazi occupation. For the second exhibit, the museum decided to feature the life work of Rengetsu and invited me to be the curator. To guide visitors through Rengetsu’s oeuvre, I created a catalog of the exhibition, which I would also develop into a book.

At this time, I fell seriously ill, suffering from a host of ailments—urethral cancer; blood clots; five emergency surgeries, with one conducted without anesthesia. I also experienced pains stemming from a septic blood infection, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, severe anemia, and hypoglycemia. And as a result of this duress, I became subject to whims of depression, confusion, frustration, and thoughts of suicide. I was constantly in and out of the hospital during this period. I even had two near-death experiences: one serene and blissful, merging into a vast blue sky, and the other, dreadful, fighting off demons in a bloody battle.

Although much of the time I was working on the book I had been shut up inside of dark and airless rooms, lying on sickbeds surrounded by people on their last legs, in my mind, there were only thoughts of beauty.

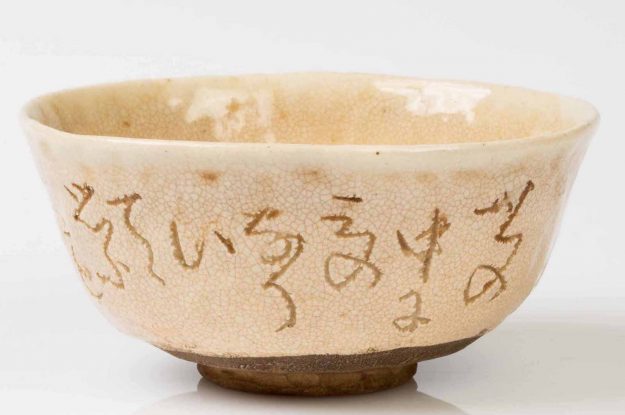

Despite my many illnesses, I was determined to continue my work on the exhibition. While lying in my hospital bed, I held the pottery for the exhibition and examined the pieces closely, one by one, in order to compose the accompanying display labels. Kneading the clay was the way Rengetsu meditated, silently reciting prayers and mantras. When I held a bowl, I could feel where she had kneaded the clay and see her very fingerprints; it was a kind of a heart-to-heart transmission. There was a natural rhythm to how the pieces were formed—it felt less like they had been made than that they had emerged. There was no break in concentration. The pottery was made with a “nonabiding mind unattached to the thoughts of beauty or ugly, free from fixed forms.” There was no projection of the artist’s ego, trying to make a statement. It could have been crafted hundreds of years ago or yesterday. Some of her pottery was of near professional quality, while other examples appear as if formed by a 10-year-old: misshapen, with kiln scorch marks, scratchy calligraphy, and messy glaze. What happened, happened. Nothing was discarded because it did not look “right.” While the aesthetics of the pieces in the show could vary greatly, their differences only created a more compelling and cohesive presentation when viewed alongside one another. A tea bowl of classic proportions and a sake flask that looked as if it were of a contemporary, abstract art design aesthetic seemed to play off one another, creating a richer insight into the artist who created them.

Although the pottery was typically of thin construction and as light as a feather, many of the pieces felt as solid as a rock. I liked to hold the tea bowls, which, to me, appeared and felt the most energetic. Certain pieces even had a subtle “buzz” to them as if they were animate. (I once stayed at a collector friend’s home and slept in a room full of antique Asian statues. At night, I thought I heard them humming.)

Since the venue was a monastery, I felt that Rengetsu’s pottery could be compared to “relics” of medieval times. It was unostentatious, with a quiet presence, not holy but “whole-ly.” That is, complete, free of artifice, capable of lifting one’s spirit. Her tea bowls were simple chalices, carrying tea meant to awaken the mind; I always referred to her eighty-five-year tea bowl as the “holy grail.” Although the monastery was built in 14th-century Spain and Rengetsu lived in a hut in 19th-century Japan, I felt the venue and artist had a profound kinsmanship.

Then I had to figure out the incised calligraphy on the bowls—Rengetsu’s trademark and major selling point. I marveled at how she wound the characters along the side of the pottery with a pick. The characters wound around the rough, uneven surface of the pottery, placed perfectly in even the tightest spaces, without hesitation. She had to have a very gentle yet strong touch. Her fingerprints are clearly visible on many of the pieces.

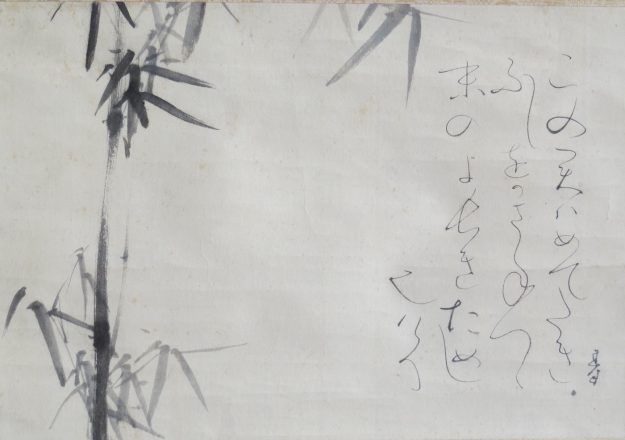

In contrast, Rengetsu’s calligraphy on paper was influenced by her martial art training—the control of the brush, the flow of calligraphy, and the spacing of the characters. There was an unbreakable steel core in her brushwork. Typically, brushwork in Japan is described as being in a “man’s hand” or a “woman’s hand.” Rengetsu’s brushwork was beyond gender—a man’s strength and determination blended with a woman’s flexibility and elegance. For healing, the balance of female and male energy is vital.

Once I got the Japanese reading, I began the translations. This came as a special challenge for me because my brain was fried from all the treatments I had been going through during that time. I got very confused, sometimes not even realizing where I was, or what was happening. When I was moved from one hospital to another, I panicked twice, calling 9-1-1. The first time because the world seemed to be ending, with everything crashing down; the dispatcher assured me it wasn’t, but it took some time for me to believe her. The second time the hospital staff actually forgot about me for forty-five minutes. I was bedridden, so I couldn’t move around; no one answered the call button or my frantic shouts. I called 9-1-1 for help, and a policeman arrived. He told me hospitalized people call 9-1-1 all the time, sometimes to investigate the monster under their beds. Once, I evidently tried getting out of bed and asked the nurse, “Where is my gun?” The nurse replied, “Why do you want a gun?” I told her, “I need to go fight for Ukraine.”

Despite my shaky grasp of reality, I tackled the translations. While the phrases in her poems are simple— “moon over the cherry blossoms,” “a warbler chirping in plum trees,” “the sound of wind in the pines,” “willows along the river,” “celebrations during festivals,” and the like—the images floated about me in three dimensions and in vivid colors. I could hear the birds singing in a full-throated chirp. I was inside of the translations rather than figuring out the words from outside. The translations changed day to day, depending on the vision I had of the poem. Later on, I was puzzled with how I came up with certain translations and had to change them completely. Here is one of the simpler poems in the latest incarnation.

Living deep in the mountains,

I have grown fond of

The sound of the murmuring pines—

On a day the wind does not blow

How lonely it is.

My effort is described in Japanese as a shinken shobu, “fight to the death.” The time had come to publish the manuscript. I was blessed to have had an enthusiastic, patient, and understanding editor who guided and encouraged me throughout the production process. (We once consulted on the phone as I was being wheeled off to the operating room.) Although much of the time I was working on the book I had been shut up inside of dark and airless rooms, lying on sickbeds surrounded by people on their last legs, in my mind, there were only thoughts of beauty. At my lowest point, what kept me going was my ultimate aim: “I cannot die until the book is published and in my hands.”

This is to say, I’ve finally made it. And I thank Otagaki Rengetsu for saving my life.

◆

All the items shown in this article are from The Lotus Moon: Art and Poetry of the Buddhist Nun Otagaki Rengetsu by John Stevens. Floating World Editions © 2023. Used with permission from John Stevens.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.