The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong

The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong

By Gyalo Thondup and Anne Thurston

PublicAffairs; April 2015

301 pp.; $27.99 (Cloth)

In the winter of 2001, I lived in the foothills of the Himalayas in the Darjeeling District of India, while studying under the Kagyu lama Bokar Rinpoche. Every night I looked out across the valley, with my one-year-old son and his father, to the town of Kalimpong as its electricity cut out. With so little to measure or mark our days, this became a kind of event, something we anticipated. The only thing I knew then about Kalimpong was that its egg noodles were fresh, delicious, and famous. But just how famous, I had no idea.

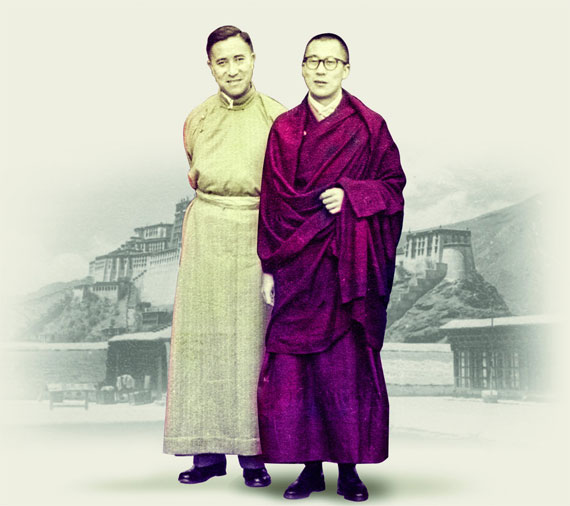

As it turns out, most residents of Kalimpong were also unaware of their noodles’ origins. Only when Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama’s older brother, took up a more permanent residence there in 1999, did his identity as the noodle maker become known. And yet even with the publication of his memoirs, The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong, Thondup remains a fiercely private man. Given his position as a political attaché, it’s evident that his skillful tact has been exactly what’s allowed him to serve the people of Tibet for so many decades.

It is a sense of duty and honor that has inspired Thondup to put his experience in pursuing Tibetan visibility and diplomacy to the page. He does so despite his anticipation of controversy and criticism from all sides—“Tibetans, Chinese, Indians, Americans, the CIA.” But, as he claims throughout the book, in the face of impossible decisions, he has always made those he thinks best for Tibet.

Thondup, who was born in in Amdo in 1929, has led a rich and intriguing life. The resulting memoir is part cosmopolitan spy novel and part heartbreaking tale of an uprooted, often-betrayed refugee.

“Of the five male siblings who lived to adulthood, Gyalo Thondup alone did not become a monk,” writes coauthor Anne F. Thurston in the introduction. “Instead . . . he was groomed to serve his brother on matters of the state.” This education began in earnest in 1945, when Thondup was sent to China to study, but not before making his way to India first. At the twilight of British rule, Calcutta was a thriving, modern city, in which the teenage Thondup, coming from rural, religious, and insulated Tibet, was exposed to not only Charlie Chaplin movies and five-star hotels but also paved streets, telephones, and steam engines. Thondup’s travels convinced him that secular education was essential for Tibet’s survival.

He went on to live in China for the next several years, where he learned the language, befriended then-president Chiang Kai-shek, and immersed himself in 5,000 years of Chinese history, which verified that Tibet had never been considered part of the “motherland,” as the communists would soon claim. From there, Thondup and his Chinese wife, Zhu Dan, would live, among other places, in Taiwan, San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Darjeeling, where his wife eventually established the still-operating Tibetan Refugee Self Help Center. In 1952, they bought a small plot of land in Kalimpong, just outside of Darjeeling and not far from the Tibetan border, and in 1980, the couple opened the noodle factory that’s been running ever since, throughout Thondup’s extensive work abroad and even after Zhu Dan’s death in 1986.

After the Dalai Lama’s escape to India in 1959, the two brothers collaborated on what became their first press conference, one that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru never wanted to happen. Their goal had been to publicly refute Chinese propaganda and to declare Tibet a sovereign nation. It was then that the Dalai Lama stated, “wherever I am, accompanied by my government, the Tibetan people recognize us as the government of Tibet.” With this establishment of the Government-in-Exile, Thondup was formally appointed foreign minister, and he began seeking international support.

Behind the scenes and unbeknownst to his younger brother, Thondup coordinated with the CIA, doing so well into the 1960s. The clandestine organization trained a small but steady stream of Tibetans—volunteer resistance fighters—in Colorado, the Western Pacific, and eventually in Mustang, Nepal. At the time, Thondup believed that the US wanted to help the Tibetan people. It was this work, however, that would become one of Thondup’s biggest regrets. In later years, he came to realize the US was more concerned with “stirring up trouble” between India and China. Thondup now thinks that the uprisings, given “paltry support” by the CIA, only caused more deaths.

A diplomat to the end, Thondup recalls his life as a series of political events—an understandable impulse, but one that often results in less of a story than a history lesson. More often than not, Thondup’s determination to “set the record straight” insulates his account from more heartfelt, subjective truths—the complicated kind wrought with emotion and tricks of memory, but blessed with the details and insights that resonate with meaning.

Recognizing that “setting the record straight” is not so simple, Thurston, who coauthored the best-selling The Private Life of Chairman Mao, notes how her point of view occasionally differs from Thondup’s. For instance, Thondup maintains that his father was poisoned in 1947, in a power struggle among Lhasa aristocracy. In her afterword, Thurston casts some doubt on this version of the story, noting that the Dalai Lama himself remains unconvinced of any foul play. Yet precisely because Thurston expresses her skepticism only in the afterword, the logic and lucidity of Thondup’s voice are preserved. The combination of their perspectives makes for a compelling metanarrative on the inherent paradoxes of autobiography, one that ultimately enhances Thondup’s exploration of Tibet’s history.

In the final paragraph of this autobiography, one of the most poignant moments of the book, Gyalo Thondup recounts a recent meeting with the Dalai Lama, who implores him to stay healthy—and alive. “We have to return home together,” the spiritual leader, soon to turn 80, tells his big brother. The implication is that if they keep holding out, they will accomplish what everyone knows is unlikely, at least in their lifetime: a return to Tibet, together.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.