Between-States: Conversations About Bardo and Life

In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States” explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

***

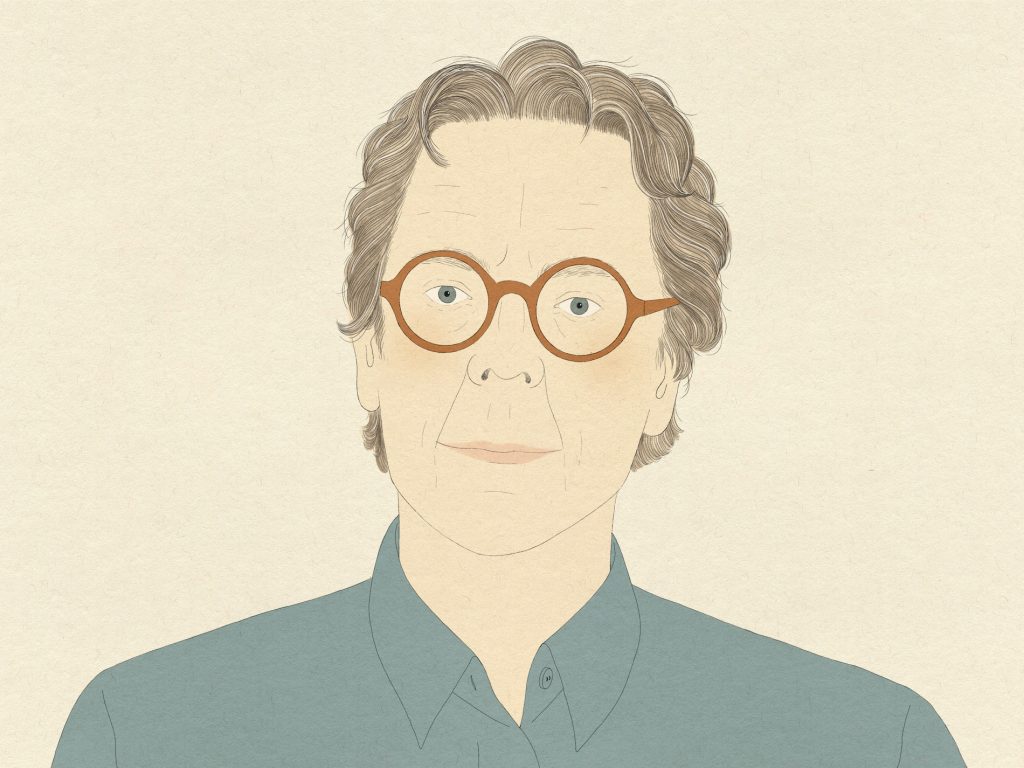

Sun House, David James Duncan’s first novel since 1992, is nearly 800 pages and took him sixteen years to write. It’s a wide-ranging tale of the search for meaning in a world where “biocide and geocide are high on the list of disasters,” and “we’re…having our hearts repeatedly broken by a human assault on the planetary tapestry of life that’s fast building toward an inconceivable climax.” Longing for a different kind of existence, the characters in the book (a student of Sanskrit, a folk singer, and a restaurateur, among others) come together to create a new community on 4,000 acres in Montana—a “solvent, spiritually awake, thirty-person dryland lifeboat.”

Duncan was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1952. His first two novels, The River Why (1983) and The Brothers K (1992), became best-selling cult classics; both won the Pacific Northwest Book Award, and The Brothers K was a New York Times Notable Book. Duncan’s other work includes a story collection, River Teeth (1996), and a book of essays, My Story as Told by Water (2001), that was a finalist for the National Book Award.

On a beautiful fall morning, Duncan spoke with me from his home in Missoula County, Montana, about why he wrote Sun House and how he has made his way forward during bardo periods of struggle and impermanence.

*

How did the idea for Sun House evolve? There are so many ways. One is that I’ve raised two daughters. They’re 30 and 32 now, and I have a first grandchild. Because of her love for the earth, my younger daughter majored in environmental studies here at the University of Montana. Information poured over her, but it dismayed me to see she was being given no cause for hope.

I’ve led an unusual life and have discovered causes of hope that aren’t familiar to the younger generation. We didn’t need another op-ed saying our consciousness needs to change—instead, I wanted to bring my tools as a novelist to storytelling that depicted people in moments when they’re experiencing a change of consciousness with their senses and their intuition, their hearts and minds.

The bardo teachings can help us find meaning in the face of the challenges and losses we encounter in life. What has your search for meaning been like? It started when I was 13. My 17-year-old brother, John, who was my closest friend, died of an unsuccessful heart surgery. He was my hero and protector, and he was gone. I ended up becoming friends with a fellow two grades ahead of me, a brilliant guy who got into Stanford on a full ride. When he left for college, there I was at this incredibly boring, violent Vietnam-era high school in suburban Portland. The worst of the teachers were racist and sexist, unintelligent and fierce, and I wanted nothing to do with any of that.

I started exchanging letters with my friend and reading the Stanford Humanities curriculum—I was bombing out of high school and reading the novels of Hermann Hesse and other greats. There was a desperation that drove me and began to help me. When a teacher at my high school realized I was committing academic suicide but reading great works, she got me into a new scholars program at Portland State. I graduated from high school with a 2.7 GPA and from Portland State summa cum laude, because I was allowed to study topics that aligned with my spiritual seeking.

My search for meaning has also been very wound up in the natural world. I went to the all-night party on the last day of high school but the next morning drove into the Cascade Mountains and hiked up to a lake, where I spent ten days by myself. The following year, I spent a hundred days mostly alone in the Wallowa Mountains, seven and a half miles from the nearest road, blissed out, charging around in all this gorgeous dolomite and marble in the northeast corner of Oregon. The year after that, when I was 20, I made a pilgrimage to India.

You experienced something remarkable in the bardo period after your brother died. What happened? I wrote an essay about it called “The Mickey Mantle Koan.” My brother John’s hero was legendary New York Yankees baseball player Mickey Mantle, and when it was clear my brother was dying, my mother wrote to Mantle and asked him to please send John an autographed baseball. Mantle did. I expected a sports relic from a hero would have some kind of healing property for my brother, and for me, but this baseball—which said, “My best wishes, your pal, Mickey Mantle”—happened to be dated on the day of my brother’s death and arrived on the day he was being embalmed. That timing threw down a gauntlet.

I called the essay “The Mickey Mantle Koan,” because, like a Zen koan, the effect I expected from the baseball failed to occur. That failure, that pain, led to an intense visionary experience. One day after John’s death, I watched a World Series game with my father. Had John lived, he and I would have gone out in the front yard after the game and played catch under some towering Douglas fir trees. After watching the game with my dad, I was alone in the house, looking out the window at where John and I used to play, when I saw my brother catch, then throw, a baseball. It was that simple. In that moment, I remembered how little John and I had needed to be happy: two scuffed-up old mitts and a grass-stained ball. I then fell through a floor inside myself, landing in a deeper, brighter chamber in which something much more than brotherly love was conveyed: Who’s to say we need even an old ball to be happy? Who’s to say we can’t do with less? Who’s to say we can’t still be happy—with no ball at all? And I was happy. Broken-openly hence boundlessly so. And with that wave of happiness, the koan was solved.

Another period of loss you’ve experienced is the end of your long marriage. How did you get through that difficult time? There’s a poem by Jack Gilbert, “Failing and Flying,” that helped me a lot. It’s about Icarus. Loosely paraphrasing, Gilbert says people forget that when Icarus fell, he did not fail. After all, Icarus flew! When he fell, he simply came “to the end of his triumph.” That phrase helped me see the end of my marriage in a positive light. Anybody who knows me and my ex knows we were great parents, our daughters are wonderful people, we have a delightful grandson, and we remain friends.

The main disorientation I experienced was losing my home and the twelve acres on Lolo Creek, where we’d lived for twenty-nine years. I had a relationship with a mile of that trout stream that I sorely miss, involving birds, wild animals, and all the maintenance I did to make the place safe. Creeks have been important to me since I was 8 years old, when my dad took me to one for the first time and handed me a nine-foot-long bamboo fly rod. We started walking up the creek, and I suddenly understood Jesus’ phrase “the kingdom of heaven is within you”; I felt I was walking deeper and deeper inside myself. I’ve worn waders and walked probably a couple of thousand miles in flowing waters since. A rod is almost optional. In keeping with what my friend Jim Harrison wrote in “Cabin Poem,” I want to finish my life disguised as a creek.

Now I’m living nearby on another trout stream. Sunlight is on the water at this moment, blazing like liquid mercury. Gazing at the ceaseless flow is a refreshing, orienting activity in the middle of a workday.

“I reached a point where I’d been writing it for so long that the only way out was through.”

The creative process is a kind of bardo between-state. In the acknowledgments in Sun House, you talk about an early draft of 600 pages where you were bogged down and struggling, mired in what you call the “middle muddle from hell.” When you hit difficult stages while writing Sun House, how did you keep going? If forward momentum wasn’t coming, I sometimes had to wait for my consciousness to evolve more before I could fix the problem.

Did you ever think the book wasn’t going to work? No. I reached a point where I’d been writing it for so long that the only way out was through. To stop would have been like stopping as you’re descending from a high peak. You can’t decide to just stay up there on the slopes. You have to finish the journey.

In the bardo teachings, not being distracted is essential to moving forward. Was it easy for you to stay focused on the book? Once I got through the “middle muddle,” it was surprisingly easy. Writing for me is a spiritual practice I love deeply. The Buddhist monk in the temple isn’t going to suddenly fall off her zafu. She’s going to sit there till the sesshin is over. Storytelling at its best is truly a practice.

In Sun House, there’s a reference to Borges’s poem “The Just,” in connection with “the invisible structures that enfold ordinary folks whenever a little love or grace flows.” The poem, you say, is about “a man ‘who cultivates his garden, as Voltaire wished,’ a man who takes pleasure in tracing the etymology of a word though it takes time, two workmen on their lunch hour enjoying a game of chess in a silence so deep the only sound is the sliding of their pieces…” What are things, aside from writing, that make you feel present in this way? I’m a closet musician. I play piano and Appalachian lap dulcimer, with custom dulcimers that I’ve electrified so I can sound like Eddie Van Halen snuck up into the mountains and is raising hell back in some ravine. But mostly, I spend large amounts of time walking. I’m drawn to being a mountain wanderer, hiking long miles on trails, communing with wild creatures.

You were committed to activism when you were younger. What role does it play for you now in living a meaningful life? I broke the story about a gigantic Canadian mining company that was going to put a cyanide heap-leach gold mine in the headwaters of the Blackfoot River, which is the celebrated river in Norman Maclean’s book A River Runs Through It. That battle was like a Paul Revere ride: Something terrible is coming! Something terrible is coming! It helped marshal a whole bunch of people, and we knew we had a good chance of winning once Native American tribes, ranchers and their cowboys, and the Rotary Club of Missoula were on the same side. Now cyanide heap-leach gold mining is banned in Montana, a huge victory. In another major victory, we prevailed against ExxonMobil’s attempt to turn three wild and scenic rivers into the main corridor between the Pacific Rim industrial countries and the Alberta tar sands.

But my feelings have changed in the last decade. I feel my narrative writing has done better work than my activism. On tour for Sun House, I experienced again and again that The River Why and The Brothers K, which are about the search for meaning, really stick in people’s minds and hearts. When I was at Powell’s City of Books in Portland recently, people started talking during the Q&A about relatives or children named after characters from both novels. The best moment was when a woman said, “My parents didn’t believe in ultrasound, so they didn’t know the gender of their first baby, but there was a name in The Brothers K they loved. That’s why I’m here to tell you I really like being a 24-year-old woman named Everett!”

What are you working on now? A big book of narrative memoirs and essays that got stuck in the chute while I was finishing Sun House. I also have two novels in the works. One is an ambitious comedy about reincarnation. The other is a graphic novel in the same meter as W. B. Yeats’s “The Song of Wandering Aengus” [recites]:

“I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout…”

To me, this poem takes place in a bardo. Aengus commits his entire life to the search for beauty, which many wise souls have equated with truth. I want to write this epic graphic novel to honor my beloved Eucharist animal, the wild salmon of the Pacific. They’re in the throes of extinction throughout the interior West, but I’m determined to celebrate the sense of wonder they’ve given me.

You’ve got a lot of projects going on. When he was in his 70s, Philip Roth stopped writing and began spending his time reading and going to concerts and seeing friends. Do you think you’ll stop writing at some point? If I make it through my 70s, I doubt I’ll be attempting to create masterpieces in my 80s. I love a lot of people and want to share the mysteries of life with them for as long as I can. But I’ll also be writing something or other for as long as my joy in the gift allows.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.