Clearly, director Lana Wilson isn’t afraid to tackle controversial subjects.

She won an Emmy for her first film, After Tiller, about four American doctors under siege for performing late-term abortions. And now in The Departure, she turns her lens on suicide, a huge issue in modern-day Japan.

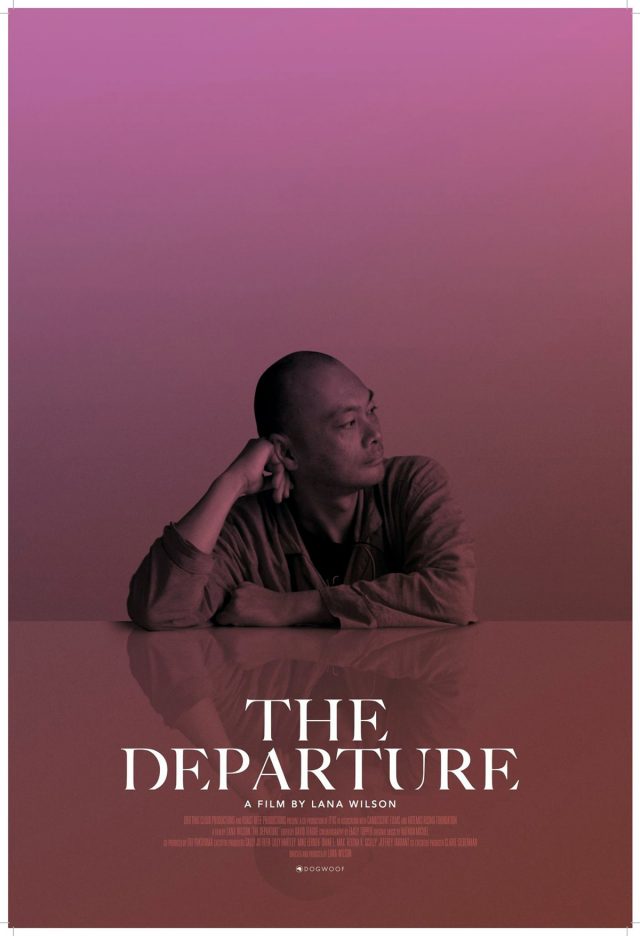

The film opens on a dancer gyrating wildly under the flashing strobe lights of a crowded club, then cuts to a motorcyclist speeding through the city at night before pulling up at a small country temple shortly after dawn. It’s a puzzling start for a film about suicide and Buddhism until we realize that both dancer and cyclist are one: namely, Ittetsu Nemoto, a 45-year-old Zen Buddhist priest famous throughout Japan for his uncanny ability to talk the suicidal back from the edge. Though he’s the abbot of Daizen-ji, a temple in rural Gifu Prefecture, Nemoto is no ordinary Zen priest. A former punk rocker and bad-boy club kid, he has dedicated his life to helping the despairing awaken to the joy of living. His success rate is astounding: since he started suicide whispering in 2004, he’s lost only one of the thousands he’s counseled through a mix of heart-to-heart talks, meditation, experiential retreats, theater games, art, dancing, and Ittetsu Net, an online network for building community, which is essential to recovery as he sees it.

The title of the film refers to the ultimate departure, death, as well as to Ittetsu’s signature retreat. “Welcome to the Departure,” he tells a zendo full of solemn-looking people. “Today we’re holding this retreat for you to find out what it means to die.” He then leads them through practices designed to not only evoke the feeling of dying but also show what they stand to lose if they take their lives. The retreat ends with the participants laid out like corpses in the darkened zendo, their faces shrouded in white cloth, as Ittetsu performs a traditional Japanese funeral rite. For the viewer, the effect is wrenching: it’s not hard to imagine how potent the experience is for those simulating their own death—or how successful a suicide deterrent it might be.

The retreat is just one aspect of Ittetsu’s immersive approach. Self-inflicted deaths, though declining overall in Japan, are rising fast among teens, as they are in the United States. But in Japan especially suicide is a source of shame so great it drives prevention efforts underground. Though funerals and bereavement top the list of a local temple priest’s duties, it is unlikely there are other Zen priests in Japan ministering so comprehensively to the suicidal and suicide-survivors. Ittetsu’s innovative methods and the scope and sensitivity of his personal involvement are highly unusual. The film shows him in intimate exchanges with clients, where his soft voice and low-key manner are deceptively simple. Closer listening reveals a skilled counselor who is deeply empathic, perceptive, and wise.

Unlike many who deal in suicide prevention, Ittetsu isn’t preachy. Visiting a divorced father despondent over the loss of his kids, he sifts through the man’s stockpile of pills without judgment, relating to him simply as one suffering human being to another.

The camera shadows the priest from long before sunup to well after midnight as by car, motorcycle, and train he visits the people who phone, email, and text him 24/7 with suicidal threats and cries of loneliness and despair. At one point, the camera zooms in on Ittetsu’s cellphone screen. It shows 50 missed calls—missed only because he doesn’t answer when he’s with a client.

Ittetsu’s ministrations to the suicidal are not the only focus of the film. The other theme is the physical and emotional toll the priest’s dedication has taken on his family as well as himself. He worries whether he has enough juice for it all. Still, he presses on. He tells his wife about a suicidal client who came to him after being too ashamed to go to the hospital for treatment: “When I was counseling, I thought, what would have happened if we hadn’t talked? That’s why I can’t quit doing this work. If I didn’t do it and they died . . .” As he rushes off to help yet another caller, his wife, small son, and mother just watch—helpless against the overriding force of Ittetsu’s commitment. On the rare occasions when he’s home, his son either angrily pushes his father away or clings to him with fierce devotion.

Dressed in his priestly vestments, Ittetsu so looks the part of a classic Zen monk that it’s startling to find out he only became one by chance. Newly married in his twenties, he was at loose ends when his mother spotted a newspaper ad: Monk wanted. No experience necessary. “So I entered the priesthood,” Ittetsu says matter-of-factly, “and here I am.” This is what we’ve been waiting for, the moment when he tells us about his Zen training. But surprisingly, the film leapfrogs over it entirely. We’d need to read Ittetsu’s press, like the 2013 profile in The New Yorker that was the genesis of the film, or an interview in the Spring 2014 issue of Tricycle to learn about his four-plus rigorous years in a Rinzai Zen monastery and years of practice thereafter before he came to Daizen-ji. Some of the most charming scenes in the movie show daily life at the temple: the priest putting on his robes, sowing rice in the temple paddy, turning on the zendo lights as his son trails along behind him.

The film takes a darker turn when the death Ittetsu must confront is his own. The chronology is murky, but having already had one heart attack, he’s diagnosed with emphysema and severely clogged arteries, conditions worsened by the relentless pressures of his job. Early in the film there’s a shot of Ittetsu poring over his day timer, trying to squeeze in yet another person in need. Toward the end of the film, he takes a stab at balancing his life.

In a flashback, Ittetsu recalls his wild and crazy youth, and the near-fatal motorcycle accident at 24 that turned around his life. What drives his suicide-prevention work, we learn, is a question that has nagged him since childhood, when his beloved uncle and two school friends committed suicide: “What made them feel they needed to die? I needed to know the reason.” In an exercise on discovering what makes life worth living, participants write down on separate bits of paper three things and three people important to them, and three things they would like to continue or try. Then they progressively whittle down the nine choices until they’re left with only the thing they value most—and then that too must be tossed away. “I think it’s important for people to know death means you’re disappearing forever, and you’ll be losing something important,” Ittetsu says. “So we find things that would be hard to lose and then we focus on treasuring those.” On Ittetsu’s last paper are just two words: My son. Ultimately, his teaching is as much about embracing life as about facing death, and he offers hope for all, not just the suicidal.

The film ends as it begins, with Ittetsu busting a move in a crowded club. Dancing till dawn, alone or in raucous gatherings of his suicide groups, is his tension reliever. “Have fun!” he continually counsels others. But there is something slightly desperate—and desperately poignant—in his struggle to follow his own advice.

The Departure (2017), directed by Lana Wilson. In Japanese with English subtitles, 87 minutes. More information available at www.thedeparturefilm.com.

Learn more about Ittetsu Nemoto‘s Rinzai Zen training

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.