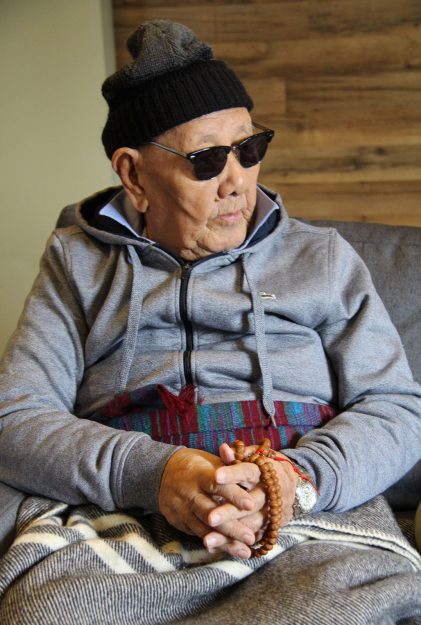

In 1959, tens of thousands of Tibetans followed their spiritual leader, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, into exile. Many of us are familiar with the dramatic flight through the Himalayas to the Indian subcontinent, and the 1959 “Tibetan Uprising” that occasioned it. But few experienced it like Gyaltsen Choden did. Born on January 1,1921, Choden is among the uprising’s oldest living survivors. At the time, he was a tsedrung, or monk official, serving as one of the caretakers at Norbulingka Palace, the Dalai Lama’s summer residence in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital city.

At the point when the Dalai Lama’s story goes to India, Choden’s trial begins at Norbulingka. His role was to stay behind and create the impression of normalcy so that by the time anyone noticed something was awry, His Holiness would be long gone.

Thupten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama’s principal English translator and founder and president of the Compassion Institute, calls Gyaltsen Choden’s life “a mirror of the complex story of Tibet and its people, from their rude awakening to modernity by the Communist Chinese invasion to their amazing adaptation to today’s globalized digital world.”

Jinpa explains that,“[a]s a government official of independent Tibet, Choden had the rare opportunity to see the now lost old Tibet; and as one of the Tibetan officials who joined the Dalai Lama in exile, especially as his representative in southern India, he oversaw the reestablishment and growth of Tibet’s great cultural institutions, like Drepung and Ganden monasteries, in their second home.”

(On a personal note, Thupten Jinpa adds, “As a Tibetan who grew up in exile in India, it is a source of pride and joy to see Gyaltsen Choden’s story told in Tricycle as he reaches the venerable age of one hundred.”)

In 1949, Mao Zedong formed the People’s Republic of China, and issued a call to arms to “liberate all Chinese territories.” In order to forestall a full military occupation, the Tibetan government entered into a 1951 treaty with China known as the “17-Point Agreement,” which permitted Tibet autonomy over language, religion, and local government in exchange for ceding sovereignty over its territory.

Throughout the ensuing decade, Tibet’s society was marred by increasingly violent conflict and pressing Chinese occupation. Tensions came to a head on March 10, 1959, when the Chinese General Zhang Chenwu invited the Dalai Lama to a cultural performance at his Lhasa military headquarters, instructing him to come alone without security or bodyguards. That night, Tibetans poured into the streets around Norbulingka and blocked the palace gates, ensuring the safety of their temporal and religious leader by making it impossible for him to leave the compound. Less than a week later, he fled the city for refuge in India.

Though contested, new scholarship suggests Mao may have known about and permitted His Holiness’s escape. Whether this is true or not, the facts of Gyaltsen Choden’s lived experience on the ground, and those of many others in his generation including the estimated 87,000 Tibetans who were killed during this time, remain unchanged.

As Gyaltsen Choden turns 100, his story offers a rare glimpse inside Norbulingka before, during, and after these historic events, and a recollection of his early service to the exiled Tibetan government.

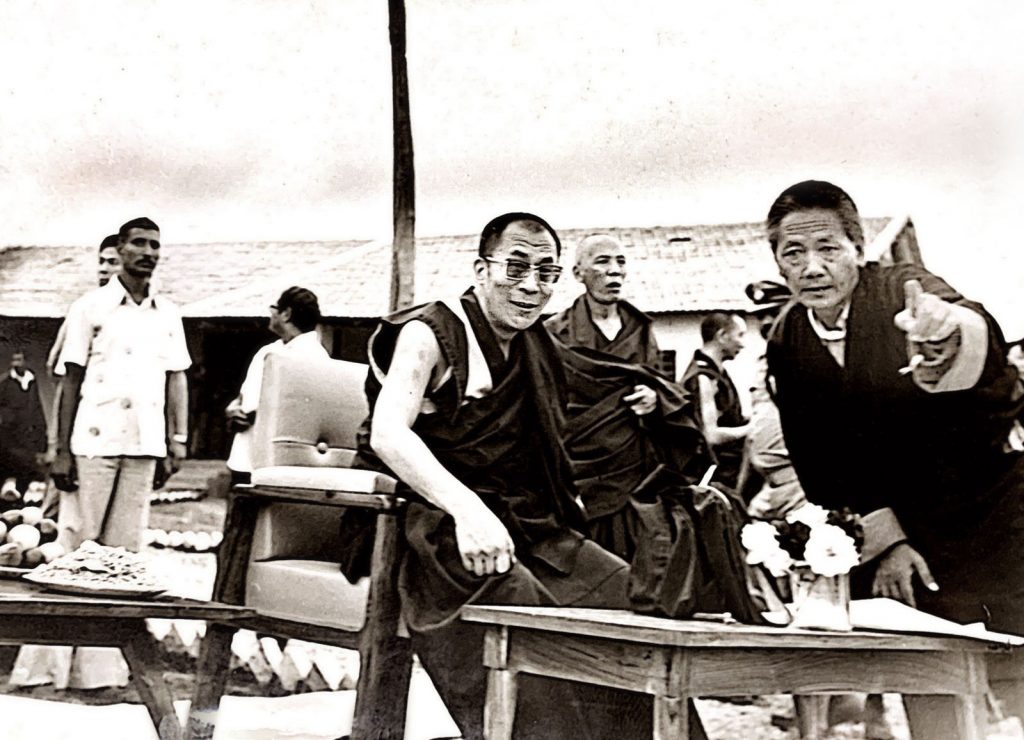

I met His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in 1940, when he began spending his summers at Norbulingka. He was five years old, but he was already bright and mature with an outgoing personality and an innate sense of equanimity. He treated everyone with respect, regardless of title or position. Over time, a number of the elder monks began to notice that the Dalai Lama was more accessible to the public than his predecessor, the more reserved but equally respected 13th Dalai Lama. When the 14th Dalai Lama gave an audience, for instance, he laughed and smiled.

In 1948, the Private Office of H.H. the Dalai Lama proposed my appointment to the Office of the Private Treasury, which was separate from the National Treasury. After the 13th Dalai Lama was forced to flee the capital city of Lhasa—first to Mongolia, in 1904, during the British invasion commanded by Sir Francis E. Younghusband, and then to India, in 1910, when troops directed by the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty marched on the capital city—the Office of the Private Treasury was established to provide for His Holiness’s well-being in case he had to escape again. It was funded with the personal possessions of the Dalai Lama, including offerings made by Tibetans in connection with prayers and dedications, and the gold, silver, silk, and precious stones that were gifted to the 13th Dalai Lama during his two-year stay in Mongolia.

During my twelve-year tenure in the Office of the Private Treasury, a strong devotion grew within me for His Holiness. I served him with confidence and a pure heart, believing him to be the embodiment of compassion, convinced that he was my savior for all my births in samsara, the endless cycle of death and rebirth.

On March 10, 1959, His Holiness was invited to attend a cultural performance at the Chinese military headquarters in Lhasa. He was told that he should attend alone, without armed security.

When the Lhasa public heard about the unusual request, they thought it was a trap—nothing short of a pretext for kidnapping the Dalai Lama and taking him to China. The night before the performance, more than twenty thousand concerned citizens flooded the streets around Norbulingka and blocked its gates. It felt as if the entire populace had surrounded the palace. There were men and women, children and seniors, monks and nuns—all willing to lay down their lives to protect His Holiness.

Ultimately, the Dalai Lama declined the invitation, citing potential pandemonium if he were to attempt to make his way through the protesters. He would not have had this excuse if the citizens of Lhasa had not taken to the streets to protect him.

Meanwhile, His Holiness summoned the Nechung oracle, the official state oracle, for guidance. The medium through whom the Nechung oracle spoke was a close friend of mine and stayed at my home whenever he visited Norbulingka. That night, the medium told me that the oracle had advised His Holiness that given the present circumstances, he should leave for India as soon as possible.

The mastermind behind His Holiness’s escape was Phala Donyer Chemo, the Chief Chamberlain who functioned as the key point of contact between the Dalai Lama and the outside world. I was told that to avoid recognition by both the Chinese and the protesters, His Holiness was advised by Chemo to depart at night on horseback disguised as a soldier. Knowing it would be dangerous for His Holiness to ride one of his own horses on the journey, as there were many spies in the palace who could easily recognize the animals, Chemo asked my first cousin Tenpa Soepa to help deliver horses from Kundeling Labrang Monastery.

My role was to stay behind. I had to keep up the appearance that nothing had changed at Norbulingka after the Dalai Lama slipped out.

Over the next few days, the situation grew increasingly tense. Clans from all parts of Tibet joined the initial protesters in creating a human shield around the palace, as the Chinese military prepared for major combat. Trucks carried armed troops throughout the city. Soldiers climbed utility poles, pretending to be electricians, and spied over the walls of Norbulingka.

On March 17, an artillery shell landed near the Northern Gate of the Dalai Lama’s private residence. The shell did not explode, but it was clear that the time had come for His Holiness to leave Lhasa.

That night, he and his entourage set out for India. It was not a moment too soon.

For the next two days, Chinese soldiers fired indiscriminately at Norbulingka and the Tibetans who had taken it upon themselves to secure its gates.

These turned out to be warning shots. At 2:00 in the morning on March 19, the Chinese military launched an all-out attack.

The shelling was relentless, like a storm blowing at the palace from all four directions. Soldiers armed with automatic weapons gunned down security guards and protesters in the street. Explosives destroyed everything they hit. When the sun came up, I bore witness to the vestiges of a merciless massacre. Human corpses and dead horses were scattered throughout the palace grounds. With brutal barbaric force, the Chinese had caused untold suffering and destroyed the Tibetan religious nation. Lhasa was lost.

At 8:00 a.m., on that dark morning, we were given word that His Holiness had safely crossed the Yarlung Tsangpo River. After breathing a deep sigh of relief, I instructed all members of the palace staff to send word to the Tibetan people that His Holiness had escaped to India and that they should follow him immediately.

The Chinese military, however, continued firing at the Tibetan people even as they fled the city. When the shelling finally stopped, the Chinese soldiers entered the palace and inspected all the dead bodies, appearing as if they expected to find His Holiness among them. On March 31, the Indian government officially announced that the Dalai Lama had arrived in their country, at which point the Chinese authorities publicly acknowledged his escape for the first time.

The Tibetan people were willing to sacrifice their lives for His Holiness to escape to India. We must never forget them. We must never forget these events.

Once word was out that the Dalai Lama had left for India, my older brother Lobsang Chonzin arrived at my doorstep. He had been on the front lines of the protests as a representative of Ganden Monastery and was insistent that we leave Lhasa without delay. But I was hesitant given my responsibility for watching over Norbulingka.

“What are you talking about?” he scolded me. “Tibet is lost. We have to run.”

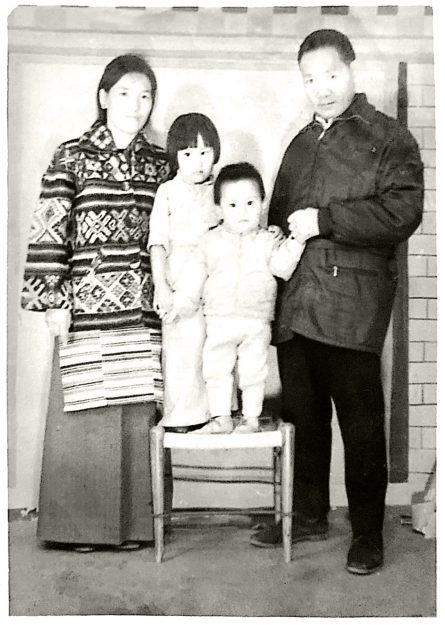

We left Lhasa on foot. There were five of us: Chonzin, my younger brother Ngawang Tenzing, who was a food supply officer for His Holiness, and two monks, Gashar Lhopa Changkya and Tsedron Thupten Nyima, from Ganden Monastery who worked for my older brother.

We took the northern route, traveling first through marshlands and then up the slopes of Mount Gephel. I was a bureaucrat and not particularly physically fit. I could barely walk by the time we reached the top of the hill. Fortunately, Changya found a horse for me to ride on the way down. After a while, we were able to secure horses for the entire group.

After three days, we arrived in the village of Taktse Phakmo Sholdungmey, where our sisters Tsering Dolkar and Jampa Pelmo lived in a nunnery. Our sisters pleaded with us to wait out the troubles and return home. They thought the Chinese would not be that harsh on the Tibetans once the uprising was over. “Hide up in the hills. We’ll bring you food,” they said, but Chonzin insisted that we keep moving. Our sisters gave us food and clothing and we crossed the Lhasa River and headed to Lhoka.

Situated a hundred miles south of Lhasa, Lhoka is home to Samye Monastery, Tibet’s first Buddhist monastery, and Yumbulakhang, the country’s first royal palace. In 1959, it was also an important strategic site and the base of the Tibetan militia, the Chushi Gangdruk. A week before we reached the city, the militia had successfully protected His Holiness by escorting him through the territory. If the route had been vulnerable to the Chinese, His Holiness would not have been able to traverse the region.

We arrived in Lhoka with war planes flying overhead and ground forces in fast pursuit. We pinned our hopes on the Chushi Gangdruk staging a formidable counterattack when the Chinese entered the city, so we remained in Lhoka for ten days to assist with the preparations. But when the Chinese military overpowered the Tibetan militia we were forced to flee.

From Lhoka, we traveled to the border town of Tsona. It was an extremely difficult journey. Food was scarce and we feared for our lives knowing the Chinese troops were following close behind. When we reached Tsona at nightfall we were conflicted about whether to push on to the Indian border that night or to rest and continue our journey in the morning. It was a difficult choice: we could either traverse the expanse between Tsona and India, which required crossing a snowy mountain pass that would be grueling to navigate in the dark; or risk being caught by the Chinese if we stayed in Tsona too long.

The Nechung medium was already in Tsona when my brothers and I arrived, so we asked him if he would advise us. When we explained our dilemma, he said, “I will ask the oracle,” meaning that he would ask the oracle that speaks through him when he channels to see if it would be willing to offer us guidance. The medium entered into a trance, then assured us that it was okay to ask the question. Drawing deeper into the trance, he advised us to leave in the morning. I had a lot of faith in the oracle and was able to rest easily based on his counsel. Those who did not have the same level of trust faced a restless night.

When my brothers and I set out on the path early the next morning, it was evident that most of the locals had already fled, leaving footprints that we were able to follow all the way to India. I was filled with gratitude, as we could easily have gotten lost had we tried to cross the mountain pass exhausted in the dark of night.

When we reached India, I felt as if my life had been saved. My brothers and I had left behind wealth accumulated for generations, our siblings, and our mother whose kindness we could never repay. Still, we were fortunate to have each other, and lucky to have arrived in India ten days before the Chinese sealed the border.

We spent a few days registering with government officials in Chu Dhangmo, India. From there, we were transferred to Mon Tawang Monastery, where the Indian government provided us with tents and food until we were taken to the Tibetan transition camp in Missamari, Assam.

We arrived in Missamari, India, in May 1959. This was the holding point for the 80,000 Tibetans who followed His Holiness to exile. There, we lived in makeshift bamboo shelters as we waited for papers granting political asylum. Once asylum was granted, we were given a letter that permitted us to travel on India’s trains and buses to the various Tibetan refugee settlements, most of which were located in the hill towns of northern India. Children under fifteen were sent to Dharamshala, in the foothills of the Himalayas, for schooling; able-bodied men and women went to the northern Indian towns of Kullu and Manali to build roads; the monks gathered in the city of Buxar; most others settled in the mountain town of Dalhousie where they learned crafts, such as thangka-painting and carpet weaving.

Upon receiving their papers, many families were split up, including ours. My younger brother went to Mussoorie, where he served as a cook for His Holiness. My older brother joined the monks in Buxar. I stayed in Missamari to help process refugees.

When our work in Missamari was complete, the Dalai Lama’s brother, Gyalo Thundop, asked me to help him launch the Rawang-Parkhang Tibetan Freedom Press, a publication dedicated to keeping the Tibetan refugee community informed about events at home and in India. I also coordinated with Phuntsok Tashi Takla, the Dalai Lama’s elder sister’s husband, on translating official accounts of Chinese history to counteract propaganda and disinformation. Finally, I was charged with helping edit His Holiness’s first autobiography, My Land and My People. The book was initially published in Tibetan for the Tibetan people, many of whom lacked an in-depth understanding of our history, culture, and the traditional role of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. With Lhasa under Chinese occupation and so many of us in exile, we felt an urgent need to tell this story.

In the 1960s, the state of Karnataka in south India, then called the Mysore State, offered His Holiness thousands of acres of land to resettle the Tibetan refugees. The gift sparked spirited debate among government officials and the monastics regarding whether the monks should be moved to south India along with the lay community. Traditionally, Tibetan monasteries were akin to universities, but there were influential Tibetans who didn’t think about monasteries as teaching institutions. They believed the monks needed to remain sequestered in the mountains of north India where they had built sanctuaries for meditation.

His Holiness was in his mid-twenties at the time, but he was very decisive, particularly on this issue. He said, “To sustain the monasteries, it is important that we give them land and space. They should be moved to the south.” By this time, I was Home Secretary of the Tibetan government in exile and responsible for much of the resettlement of Tibetans within India. When I queried how we were going to implement the plan given the resistance in some quarters, His Holiness assured me, “I will take care of the discussions about the monasteries, your job is to move the monks.”

The decision to rebuild Ganden, Drepung, and Sera monasteries among the lay community in south India was one of the most important decisions His Holiness made for the long-term continuity of the Tibetan people. The presence of a vibrant Tibetan community was essential to the monasteries’ ability to preserve our language and culture. If they had remained scattered in the mountains, they may not have been able to fulfill this imperative role.

In many ways, this has been the greatest success story of the Tibetan community in exile: the fact that we were able to rebuild our monasteries and preserve the foundations and full depth of our knowledge and teachings not only for future generations of Tibetans but for the entire world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.