Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

This week Jeff explores paintings of cityscapes in the Himalayan Buddhist world.

Himalayan Buddhist Art 101: Cityscapes

Charts, the topic of last week’s installment of Himalayan Buddhist Art 101, are one of the three broad categories of subjects depicted in Himalayan and Tibetan painting. This category includes popular images such as mandalas and Wheel of Life paintings. Cityscapes, another type of chart, constitute a far more limited sub-category with fewer paintings, but are interesting because of the insight they provide into the social and architectural environment of Tibet and surrounding regions.

Cityscapes are a late development in painting and only become commonplace after the 17th century. The earliest examples follow a standard composition format with a central human teacher or deity surrounded by visual vignettes that include depictions of well-known temples, monasteries and towns. Many of these early representations are accompanied by inscriptions identifying the name of the site.

Inscriptions always make the job of  identification easier. When the name of the location is omitted, the site must be identified by comparison with architectural features in other paintings, extrapolation from the overall context of the painting, or, when available, recourse to early 20th century black-and-white photography of monasteries, temples, and towns.

identification easier. When the name of the location is omitted, the site must be identified by comparison with architectural features in other paintings, extrapolation from the overall context of the painting, or, when available, recourse to early 20th century black-and-white photography of monasteries, temples, and towns.

The town of Lhasa is the most popular subject of cityscape paintings. Shigatse’s Tashi Lhunpo monastery, home of the Panchen Lamas, along with a number of other towns and monasteries such as Ganden and Labrang monasteries, are also popular subjects.

The importance of Lhasa is obvious. It is popular because of the Dalai Lama, but a lot of the credit must also go to the architectural wonder known as the Potala Palace. Historically, the Lhasa Cathedral (Jokang) was—and still is—considered to be the spiritual heart of Tibet.

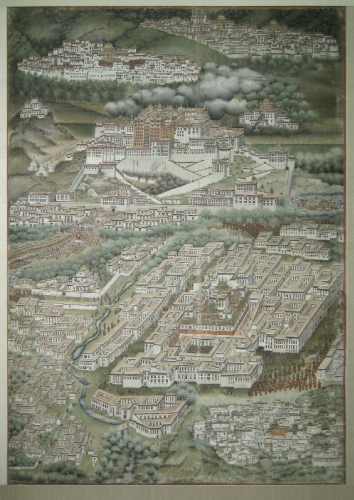

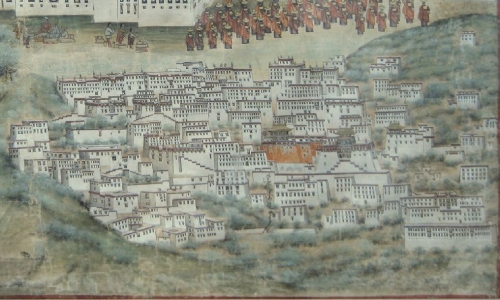

The example here is Mongolian, painted in the early 20th century. It resides in the Zanabazar Museum in Ulan Bator. The composition succeeds in arranging all the essential architectural sites of Lhasa within a single work, with the Potala Palace and Lhasa Cathedral dominating the composition.

The example here is Mongolian, painted in the early 20th century. It resides in the Zanabazar Museum in Ulan Bator. The composition succeeds in arranging all the essential architectural sites of Lhasa within a single work, with the Potala Palace and Lhasa Cathedral dominating the composition.

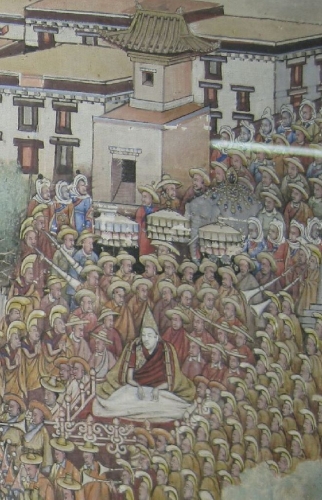

In addition to being a wonderful painting with almost endless detail, there are at least two fascinating elements from a modern art perspective. The first of these is a scene depicting the 13th Dalai Lama at the head of a large procession, located at the middle-left of the composition. The artist appears to have used a well known black-and-white photograph of the 13th Dalai Lama to capture a true likeness. The second, located at the bottom-right portion of the painting, is a depiction of Lhasa’s Ganden Monastery. This monastery is located approximately thirty miles east of Lhasa. The image of Ganden is also based on a well-known black-and-white photograph from the early 20th century.

In a religious and devotional context, cityscape paintings are sometimes acquired as souvenirs that serve to remind of successful pilgrimages to the most important holy sites of the Himalayan Buddhist world.

Learn more about this cityscape painting here.

Learn more about the topic of cityscape paintings here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.