Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

This week Jeff tells us about the Wheel of Life.

The Wheel of Life (bhavachakra) is one of the most recognized images in Himalayan art, perhaps second only to the Buddha. Anyone who has travelled to Asia, the Himalayas, or other Tibetan cultural areas will know that the Wheel of Life is commonly seen as a mural on the outside entrance wall of almost every monastery or village temple. It is also painted as a portable scroll composition and found in private shrines and homes.

The Wheel of Life (bhavachakra) is one of the most recognized images in Himalayan art, perhaps second only to the Buddha. Anyone who has travelled to Asia, the Himalayas, or other Tibetan cultural areas will know that the Wheel of Life is commonly seen as a mural on the outside entrance wall of almost every monastery or village temple. It is also painted as a portable scroll composition and found in private shrines and homes.

The earliest known Wheel of Life depiction is painted on a wall in the Ajanta Cave complex in India. The actual origins and design are believed to have been taught by Shakyamuni Buddha himself; it is more likely, however, that the concept of the visual form of the Wheel of Life arises from descriptions in the Buddhist Abhidharma literature.

What is consistent from the time of the Ajanta depiction up to the present is the circle (wheel) divided into pie shaped sections (spokes) and meeting at a central smaller circle (hub). The Wheel of Life paintings of today generally have four, five, or six sections. The Ajanta wheel had more sections—most likely not fewer than eight. The general design does not need to be limited to just the traditional wheel, however. Since the 17th century, artists have created vertical and horizontal depictions of the six realms of existence. Though it is difficult to label them as true depictions of the Wheel of Life (since they are not a wheel), they do contain the most dominant element in the composition, which is the six realms.

In some Wheel of Life compositions the artist might choose to favor one subject over another, such as highlighting the human realm. This might mean that the artist devotes more painting surface for the drawing of detailed figures, houses, tents, and maybe a recognizable teacher or a well-known architectural structure. Other artists might devote half of the space alloted for the six realms to just the hell realms, each depicted in great detail.

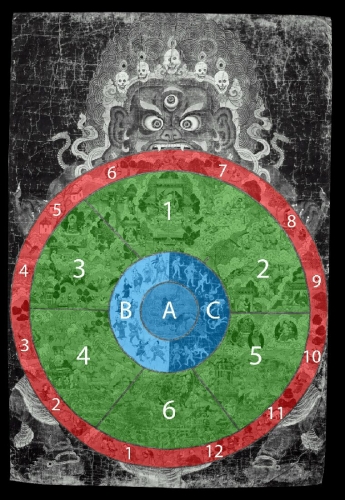

Even though there is a tremendous variety of the styles and types of the Wheel of Life paintings, they most often include five basic elements. These five are the (1) inner most circle (center, hub), (2) second circle, (3) third circle of pie shaped sections of varying number, (4) outer circle of twelve sections and finally (5) outermost wrathful figure that clutches the Wheel of Life with both hands and both feet.

Even though there is a tremendous variety of the styles and types of the Wheel of Life paintings, they most often include five basic elements. These five are the (1) inner most circle (center, hub), (2) second circle, (3) third circle of pie shaped sections of varying number, (4) outer circle of twelve sections and finally (5) outermost wrathful figure that clutches the Wheel of Life with both hands and both feet.

There are some traditions of Buddhism that have standardized a style and list of essential elements that make up a “correct” Wheel of Life painting. In the end, however, it is not about “correct” or “incorrect.” Wheel of Life paintings are a development that is based on a very old Buddhist idea coupled with tradition, the commissioner of the work, and the artistic skill, freedom and expression of the artist.

To learn more about the Wheel of Life, click here and here.

To learn more about the images you’ve seen in this post, click here (image #1) and here (image #2).

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.