The day after the beloved poet Mary Oliver passed away, I awoke to an inch of fresh snow here in northern Manhattan. Later that morning, I walked my dog to the city park near our apartment. Soon after we entered, I unclipped her leash, and off she ran into the nearest open field. I watched her romp through the glimmering snow, bounding and ecstatic, for what felt like a long time.

“You should know,” Oliver wrote in her 2013 collection Dog Songs, “that of all the sights I love in this world—and there are plenty—very near the top of the list is this one: dogs without leashes.”

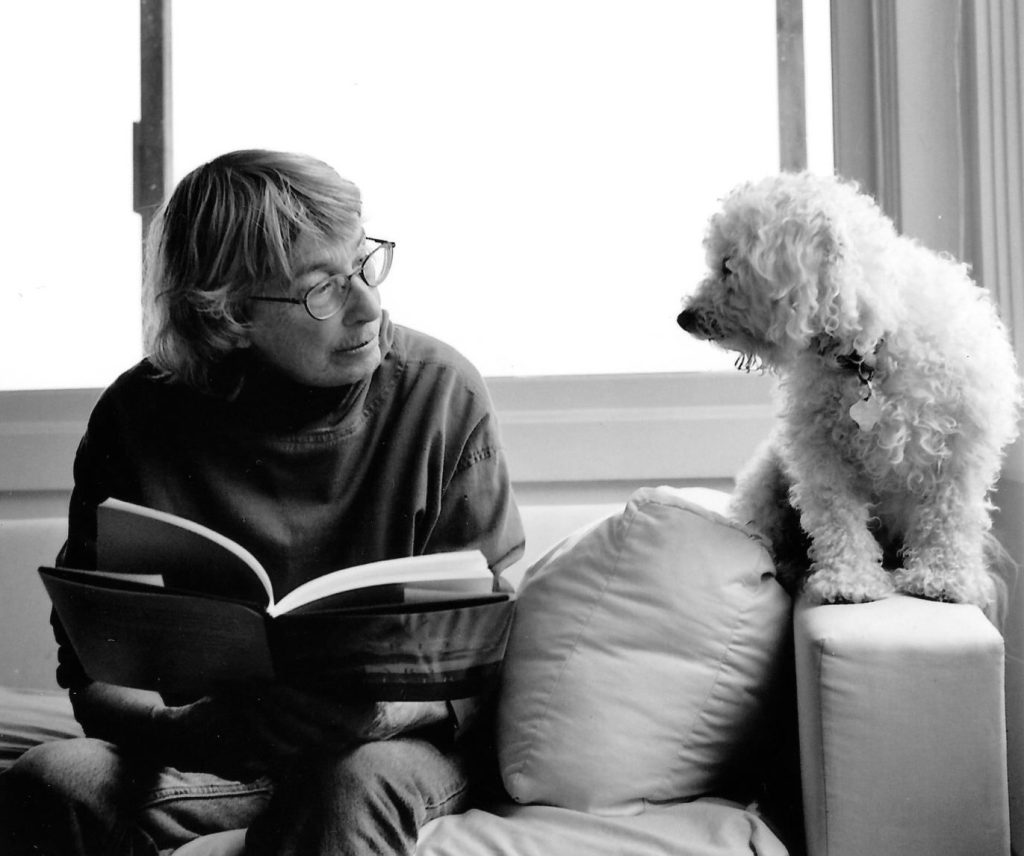

Oliver died from lymphoma on Thursday, January 17 at the age of 83. Many spiritual seekers, myself included, were deeply impacted by Oliver’s remarkable body of work, which was characterized by the rapture and joy that emerged from her devout attentiveness to the particulars of nature. She was a prolific writer whose work received many awards and accolades. Her collection American Primitive received the Pulitzer Prize in 1984, and in 1992, she was awarded the National Book Award for New and Selected Poems.

Over the past six decades, her 20 volumes of poetry inspired many to move deeper into our shared existence by way of her local world, and to do so with both tenderness and urgency. Much like the work of Whitman, Emerson, and Thoreau, many of her poems celebrate, question, and marvel at the workings of nature and of ourselves. Her words invite readers to stand beside her and observe wide-winged herons and curious muskrats, to peer closer at sugar-eating grasshoppers and laboring ants. Through her clear eyes, readers can watch the pink light rising over the marshland, the delicate and slow opening of a single pinecone, and the white faces of the stars shimmering on a frigid winter evening.

Throughout her life, Oliver’s work attracted Buddhist practitioners and meditators alike. The Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of California, San Diego incorporates her poems into its classes, and several poems in her body of work—specifically “What I Have Learned,” “Toad,” and “The Buddha’s Last Instruction”—directly reference meditation or Buddhism.

In the concluding lines of her poem “On Meditating, Sort Of,” Oliver celebrates impermanence with a quick and casual flair:

Of course I wake up finally

thinking, how wonderful to be who I am,

made out of earth and water,

my own thoughts, my own fingerprints —

all that glorious, temporary stuff.

In a recorded dharma talk at Ancient Dragon Zen Gate in Chicago, Taigen Dan Leighton, a Soto Zen priest, referenced Oliver’s famous poem “Wild Geese” while reflecting on the teaching of the Middle Way. Koshin Paley Ellison, the co-founder and co-guiding teacher at New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care and author of upcoming Wholehearted: Slow Down, Help Out, Wake Up (June 2019), shared with Tricycle a personal reflection dedicated to Oliver:

“Your luminous poetry was not social, and deeply [teaches] me again and again today how to express attention in words. As a poet and as a teacher, I continue to return to you for the words to illuminate what I have wanted to say and not sure how. Bless you for you being truly yourself and for guiding and encouraging us to pay attention and let go.”

Oliver was born on September 10, 1935, and grew up in Maple Heights, Ohio. After graduating high school, she attended both Ohio State University and Vassar College, but did not receive a degree from either institution. As a teenager, she traveled to the estate of the famed poet Edna St. Vincent Millay in Austerlitz, New York, where she worked alongside Millay’s sister Norma organizing the late poet’s papers. During this same period she met her life partner, the photographer Molly Malone Cook. The two ultimately settled in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where they lived and worked together for over 40 years.

While many of her poems honor the beauty of the natural world—much of which she observed in and around Provincetown—others reflect an intimate sense of suffering. This nuanced compassion is perhaps one of the greatest reasons Oliver’s work is so beloved. Her tone is quiet and reassuring, and her suggestions are direct, guiding, and unafraid. She does not shout, or grip readers and pull them toward her; she simply beckons. In the first two lines of her poem Lead, for example, she welcomes the reader to consider her experience in a gentle yet unswerving manner: “Here is a story / to break your heart. / Are you willing?”

In the few rare interviews she granted, Oliver reflected on her own personal challenges, which included childhood sexual abuse, poverty, cancer, and Cook’s death in 2005. One of her last interviews was on the public radio show On Being with host Krista Tippett in 2015, shortly after the poet had relocated from Provincetown to Hobe Sound, Florida.

In a reflection shared with Tricycle, Tippett recalled her 2015 interview experience with Oliver:

As I drove to Mary Oliver’s house in Florida, where she moved after Molly Malone’s death, my producer texted: “She wants to smoke during the interview. Are you OK with that?” Of course I was OK with that. I could scarcely believe the good fortune that she’d agreed to this interview. And so we talked while she smoked. I already knew, from diving deep into her work, reading between the lines as much as in them, that she defied any caricature of a nature-loving saint imagined sometimes by her readers or the poet-lite imagined by her critics.

Her delight in the world’s beauty was hard-won. Her walks in the woods began as refuge from a violent childhood; mushrooms and berries were her meals in a hungry early adulthood. Yet she offered all this up to us as devotion, rendered it in words that stilled spirits and saved lives. She never left home without her notebook, she told me, and since that day neither have I. My work has ever after been imprinted by a phrase she both articulated and embodied, life-giving in its potential for our contemplative traditions and our interactions with each other: “listening convivially.”

Oliver’s work often invites readers—by way of her own example—to gaze upon their grief, despair, and loneliness, but she does not belabor those aspects. Instead, her words encourage readers to turn toward something larger. This shift in focus from an intimate, personal experience to the interconnected movements of the wider world appears throughout her work as an element that seems both elemental and mystical. In her collection A Thousand Mornings, she writes:

I go down to the shore in the morning

and depending on the hour the waves

are rolling in or moving out,

and I say, oh, I am miserable,

what shall–

what should I do? And the sea says

in its lovely voice:

Excuse me, I have work to do.

I first met Oliver at a reading in October of 2013, when she traveled to New York to promote the release of Dog Songs. My friend and I were among the first to arrive in the crowd. While we chatted, a bookstore employee passed around small sheets of paper and told us that we could write questions for Oliver, who would select them at random to answer. I wrote down two questions, hoping she might read one of them.

After reading several poems and two short essays, she began to select questions from the crowd out of a small box. She read several aloud, but tossed them aside as if she couldn’t be bothered to answer them. I started to feel both tense and defeated, wondering if my questions were too trite for her to consider. Then, almost immediately after that thought, she read one of my questions:

“What content do you choose to leave out of your work?”

She paused for a moment without looking up from the paper. I held my breath.

“Well,” she said softly, leaning into the microphone. “A lot of poetry these days is sardonic and full of sarcasm. I leave that stuff out.” She then looked up from the piece of paper in her hands, on which my handwriting was scrawled.

“Yes,” she said, shrugging. “I guess I just prefer hope.”

Now, six years later and six years older, I find myself wishing I could ask Oliver many other questions. How do I forgive? What is it like to die? And also: what did you mean by “preferring hope?”

I read her poetry often. I share it with people I love. Her volumes sit on my bedside table and unfold in my open hands. I still don’t know what hope is, exactly. Maybe it’s the freedom my dog feels the moment she knows she can run wild in the new snow, or perhaps it’s the mysterious smallness I feel when standing in front of the churning sea. I imagine, though, that Oliver might say hope is this and only this: a fierce and disciplined willingness to look deeply at the world, and to let whatever arises emerge as it must and then fall away.

Oliver said that the reason she gave so few interviews is that she preferred to let her work speak for itself. On the matter of hope, then, I consider the final lines of the poem “May,” which was published in her 1994 collection White Pine:

“After excitement we are so restful. When the thumb of fear lifts, we are so alive.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.