The following story was adapted from an upcoming novel by the author.

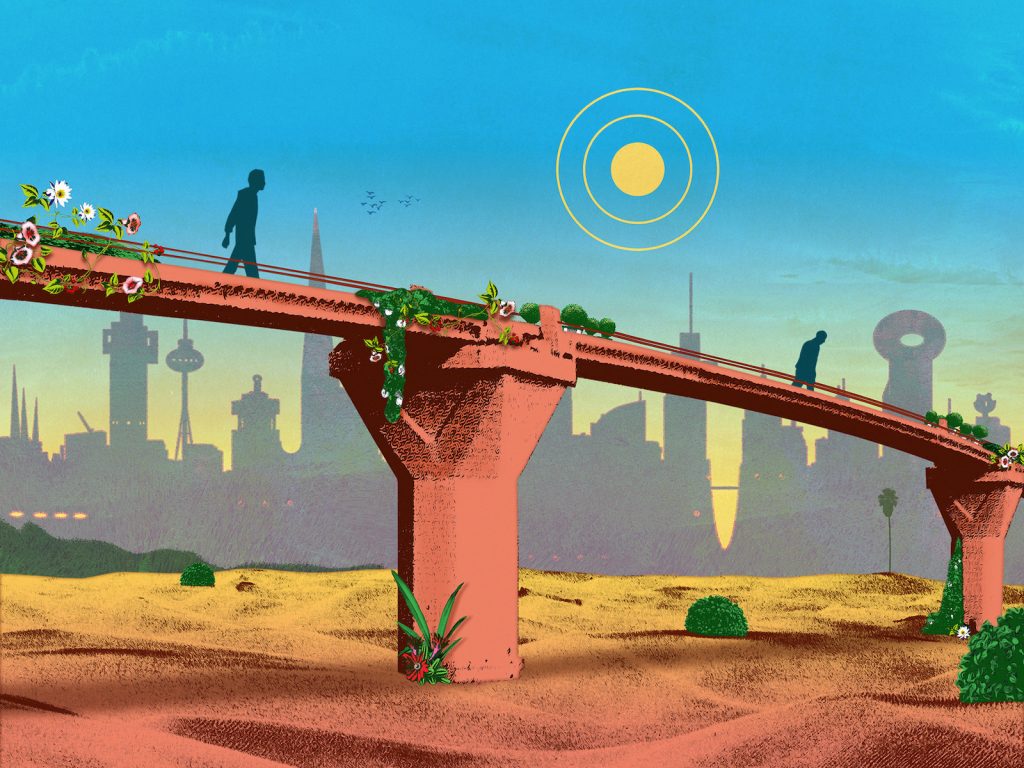

In the peculiar time span known as the 2020s, the residents of a dying nation known as the United States—who’d been oversaturated and over-traumatized with information—elected as their leader a manic-depressive failed actor turned reality TV star. With an oversized ego, a broken heart, and no real experience or interest in governing, the first millennial president made the secret decision to devote all the powers of his office to building “the Path,” a contiguous footpath that would circle the entire planet. The goal of the Path was twofold: to deliver unity and enlightenment to an atomized world, and to rewin the allegiance of the President’s ex.

To better know, feel connected to, and eventually manipulate his people, the President would privately turn to an anonymous social media account, which consisted of either utopian or dystopian travelogues about the new cities that were allegedly emerging beyond the President’s ability to see from his self-isolation in the nation’s capital. Wanting, naturally, to capture the source of the travelogues’ insight, the President located and kidnapped their author, an urban nomad and former Buddhist monk called the Tourist, whom the President would adopt as a secret spiritual advisor. In those brief moments between the collapse of one pillar of the American dream and the next, the Tourist would soothe the President’s existential dread by telling him stories of the so-called “New American Cities.”

These are the stories of Sunyata Woods and Sankhara Rapids.

Sunyata Woods—City of Somethingness

After fleeing Cohenville in terror—chased by a man in traditional black samue, swinging a perfectly rounded white stone in a leather sling above his head, with a disturbingly untroubled look that made me realize I was not as nonattached to my physical survival as I had previously thought—I resolved to get as far from that city as I could. Whether I succeeded or not can be debated, as before long I found myself arriving in Sunyata Woods, Cohenville’s sister city and rival for the title of the Zen capital of the empire.

For all their uniquenesses, cities do have kin—rivals, antagonists, soulmates—bound together by culture and karma and markets. But while Cohenville sought to shun and punish tourists, Sunyata Woods embraced them. And why? Why does Sunyata Woods advertise her attractions and her citizens’ meditative achievements on televisions across the empire, during bodysurfing competitions and reality shows about modern gold miners, no less?

It is said that, for all the Sunyatans’ excellence in the sport of emptiness, they do cling to a certain ember of self, which makes them more relatable to us than the Cohens, and safer to visit. Sunyatans have names and living wills, the barest minima of personalities and bank accounts.

If you visit Sunyata Woods, you can ask the citizens (they are a curious people, who maintain no defenses against the curiosity of others): if you accept the teaching of the mind’s innate emptiness, and of the self as an illusion that inevitably perpetuates suffering, why do you not go as far as the Cohens? Why do you not strive to eliminate or surrender every trace of a self, by any means necessary? What advantage does maintaining a self offer the true seeker, who is a tourist toward liberation, who dreams of no destination more than whatever place or nonplace is beyond suffering?

The Sunyatans will happily elaborate upon the differences in their and the Cohens’ understanding. Cohens say they prize emptiness, but if you follow their logic upstream, you’ll find it flowing from a belief in the opposite of emptiness—that the universe is completely saturated with being, which fills even the spaces between the things that make up the things that make up the atoms. Cohens believe that by emptying the self, which serves to separate the inner world from the outer, that the unification of those two realms can be achieved. When the self is dissolved, the world floods in to fill the space with itself, subsuming the emptiness.

To the Sunyatans, this is an abomination, for Sunyatans believe in actual emptiness as the original and final thing, and this is what they’re after. They grant the Cohens the supposition that there’s an innate somethingness to being, which like the most invasive species or gas or government colonizes even the smallest spaces, in between even whatever it is that space is made of. But for the Sunyatans, the self isn’t only an illusion. It occupies some liminal category between something and nothing that, when sufficiently thickened and purified, can keep the two from interpenetrating. A perfectly cultivated self, the Sunyatans’ mythology says, creates a kind of border around the only true emptiness there is. Without such a self, there’s no quarantine to effectively frame and contain the holy vacuum, to keep the somethingness of the world from flooding in.

These dogmatic fineries will mean little to the Tourist, except that the Sunyatans can’t really be known except through their passion about them. The Sunyatans use their selves—and bodies and relationships, jobs and possessions—as instruments to advance the collective evacuation. Above all—and this is what really separates them from the Cohens—they use their children. While Cohens are morally forbidden from creating and legally forbidden from raising children, Sunyatans are equally compelled to create this deepest form of attachment, which makes for them, as it does everyone, the worst sufferings of mind, which go on to encapsulate the profoundest blisses of emptiness when sitting in meditation.

The meditation the Sunyatans practice and rigorously drill their children in is also unique. Rather than surrendering thoughts of self, from birth young Sunyatans are trained to cling to them with all the grip-strength of competitive rock climbers. The little Zensters spend all their days at elite self-academies, where they learn to achieve ever more rapid, resilient, sustained, and artful generations of self-cultivation, so strong that none of its inner nothingness will be converted to somethingness by the generative power of witness.

It will be unsurprising, then, to learn that it’s from Sunyata Woods that all the Zen Champions of recent memory have emerged. Certain wunderkind, tracked from an early age for achievement and fame, receive corporate sponsorship, and even private tutelage from the great masters. They demonstrate their aptitude in meditation Olympiads, in which they’re subjected not just to raucous crowds and live international broadcasts but also the latest in biofeedback and neural imaging, which yields True Emptiness Scores across the most imaginative of tortures and disturbances—frozen mats, needle pricks, and cigarette burns to their knees on the block, other mortifications of the flesh, insults offered from one’s own parents and romantic interests, shaming and exile from one’s community—none of which, when all goes well, corrupts the wall of self or the victorious emptiness the children protect inside. Observe the Sunyatan champion celebrating his supremacy on the podium, the ring of fire around the pupils that have narrowed to the point of vanishing, inside which is contained the unspoiled emptiness that is his true and only prize.

Sankhara Rapids—Where the People Cannot Remember

Just as many cities share the same name—we have many Franklins and Washingtons and Greenvilles—there are also many cities in this amnesiac land known (and forgotten) as places without memory. But only in Sankhara Rapids is that forgetting codified by writ of law. It’s not that the Sankharans are neurophysically unable to remember, nor that they don’t want to. Rather, to engage in any act of memory is seen as a kind of violence against the authority of the present moment—like poisoning yourself with some terrible drug, which disgraces not only the individual citizen’s body and mind but also their entire vibrational field, spreading ripples of destruction into the lives of everyone else.

So the Sankharans shame and repress the memory impulse, just as many other cultures shame and repress the human’s impulses toward combat, sex, and other forms of fun. Any Sankharan found engaging in an act of public remembering is immediately confronted, by all within earshot and stone’s throw, until the sinner repents, begs forgiveness and the mercy of exile, and insists on the supremacy of the now.

The citizen and the tourist are both expected to obey the mandate against remembering even in private, even alone, when memory is most dangerous and least avoidable. Schoolchildren are taught an escalating sequence of self-flagellations, obliterating their attention’s natural wanderlust with pain. Remedial students and repeat offenders who have grown immune to such stimuli are prescribed special medicines and mantras to be administered before bed, to suppress the remembering-engine of dream consciousness. (Forgetting to self-administer these treatments is considered a sign of healing.) All Sankharans sleep tangled in hammocks that are actually human-sized dream catchers, lofted protectively above the groundwaters of memory. But all the repressed histories are like demons—cunning, determined, with no need for sleep or rest. They find and exploit any path of escape to the mind’s surfaces, moving through the slightest cracks in its defenses like air. Despite all the energy that goes toward sealing these cracks, all systems fail eventually, and the demons inevitably succeed in remembering themselves into being through the citizens’ minds, without the citizens ever becoming aware they are reenacting not only their own individual memories—regrets, losses, heartbreaks, triumphs—but also all the buried sins on which the city was founded. For Sankhara Rapids, like most cities, was taken in blood, and built in bone.

The forgettingness imposes certain limits on commerce and property ownership, which promotes a culture of taking and sharing as each moment dictates, with the model citizen often forgetting whether they identify as a generous or selfish person, empathetic or pitiless, employed or penniless, single or partnered or polyamorous. But certain spontaneous structures do emerge. At some point in my stay—I couldn’t (cognitively or legally) have said how long I’d been there—I found myself in a building that had that day decided or discovered itself to be a diner. I was studying the ways of all the ghosts of the foundational tortures, who brought themselves back into being through the oblivious locals as they unconsciously mutilated their paper napkins, impaled their breakfast potatoes with primal glee, slurped their spilled yolks through a straw. Then I saw someone burning an auroch onto the underside of her avocado toast with a lighter, and I half-realized it was her. It was the clearest view of her face I’d had in months, and yet my mind refused to fully carve the image for future retrieval, nor to understand who exactly this person was. I was compelled to sit and watch for what might’ve been hours—I’d forgotten about time—as she seemed to wonder what she was doing there in that place, as that person. I found myself following her as she left at dusk, as the day changed to night and all the violent spirits took their evening constitutionals through the people who would never remember becoming the remembering of that which they refused to remember. I watched the way she seemed to be walking nowhere but to inevitably be walking away, always away, cutting an almost drunken wave as her feet went out of their way to fall on insects and flowers without seeming to recognize them or to remember she’d ever felt any preference for sparing life rather than destroying it, maybe forgetting there was any difference between life and death at all.

⧫

Get the full story by reading the first installment, New American Cities: Cohenville, as well as more, at Fiction on Trike Daily.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.