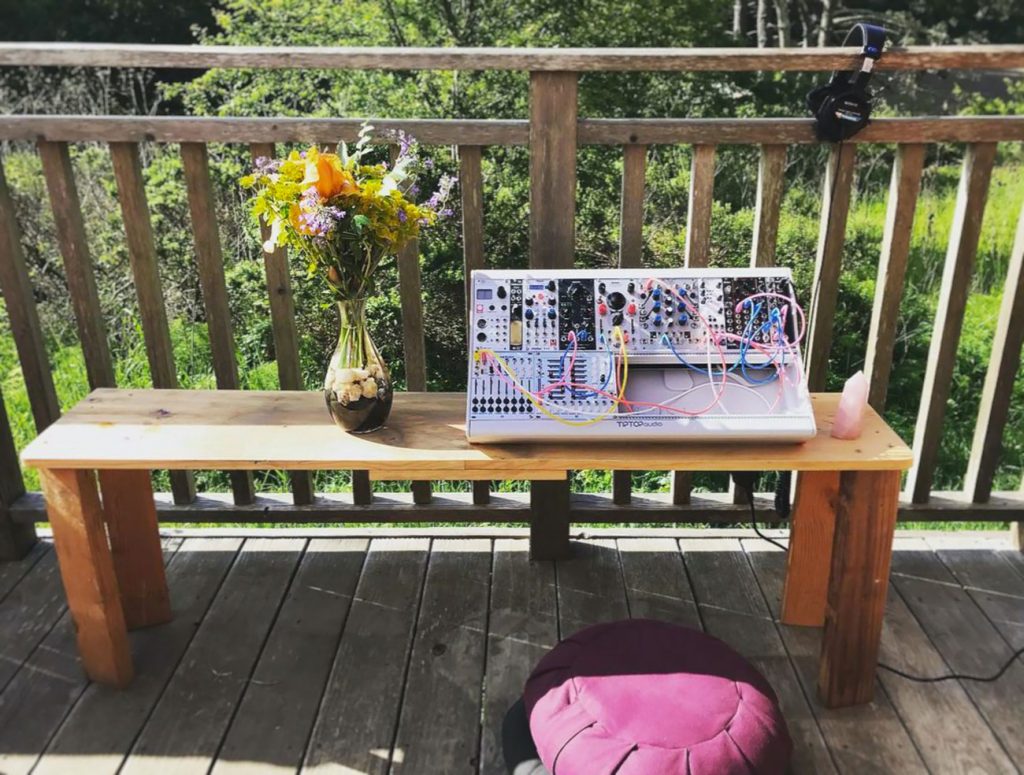

The pilgrimage began with an Instagram post: A maroon zafu, vase of flowers and a neat tangle of brightly colored cords sprouting from a modular synthesizer. In the background lay the lush green fields of Green Gulch, the Bay Area farm and Zen practice center.

The image was enough to draw S Whiteley, a 28-year-old composer and sound artist, from New Mexico to Marin County, in search of a mind similarly enraptured by Buddhism and electronic music. “It seems like I’d find my kind of people there,” he said. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

Soon enough, Whiteley found the person behind the Instagram image.

Originally from Los Angeles, Danielle Davis had brought her Eurorack synth to Green Gulch, where she lived in a yurt with an itinerant roommate, leaving her plenty of space to conduct sound experiments.

Like Whiteley, Davis’ intellect was piqued by Buddhism in college, but her practice deepened later while studying Chan in Taiwan and during her yearlong residency at Green Gulch, which is owned by San Francisco Zen Center. Whiteley, who is from New Jersey, took the bodhisattva precepts at Upaya Zen Center, where he lived in residence for eight months before moving to the Bay Area.

On the porch of the yurt, Davis and Whiteley bonded over shared interests in Zen, experimental music, the link between contemplative practices and creative states of consciousness, psychedelics, the Deep Listening philosophy of Pauline Oliveros, and outside-the-box compositions of John Cage.

“Part of the reason our collaboration is so successful is that we share a certain realm of consciousness, a certain way of being,” Davis said, “and that space is one we’ve both cultivated for a long time both within and outside of monastic communities and Zen centers. It’s a sense of: What happens from this place of stillness and silence and spaciousness? What arises? Can we listen to it? And can we follow it?”

What arose initially were strange sounds, drones, and burbles that floated from the duo’s laptop and synth through Green Gulch gardens, above the valley farm, and out to the restless Pacific ocean.

After four months at Green Gulch, Davis and Whiteley moved to Great Vow Monastery, a Zen residential center in Clatskanie, Oregon known, among other things, for its kickass marimba band. (Whiteley describes his travels from Upaya to Green Gulch to Great Vow as a “beautiful kind of organic pilgrimage.”)

During the creative practice periods at Great Vow, their improvisations blossomed into songs, eventually leading to Soundness of Mind, the duo’s first album. For a name, they chose Liila, a Sanskrit word roughly translated as “creative play” that evokes the generative flow that arises when the ego subsides.

The album has been a surprise hit for the duo, who now live in Portland. Their supply of cassette tapes has sold out and critics from discerning mainstream music sites have praised Liila’s larkish vibe. When you Google “Zen music,” you get a lot of waterfalls, wind chimes, and sleep-inducing synths. Soundness of Mind is blissfully free of such cliches.

“Whatever the layperson might assume that electronic music grounded in Zen practices ought to sound like, this 28-minute album frequently upends expectations; it is as playful as it is reverent, and the heady results push at the limits of what ‘meditative’ music can be,” wrote one reviewer.

In addition to their creative work, Whiteley, who goes by S, is studying for a doctorate in musical composition from the University of California, San Diego. Davis is training in somatic therapy.

From their temporary home in Portland, the duo spoke to Tricycle about the creative process and Zen philosophy behind two of their tracks: “not one not two” and “silent illuminating.” This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

“not one not two”

DD: This one was created during the creative practice period of about two months at Great Vow Monastery. Part of the reason we wanted to go there is because they have a strong musical influence. They have a collection of 20 marimbas and there’s a monastery marimba band…

SW: If you look it up on YouTube, there are videos, and it’s all these bald monks…

DD: Jamming.

SW: Yeah, jamming. And they’re, like, weirdly tight. They were very, very well rehearsed. And it’s very funny and wonderful.

DD: Built into the schedule at Great Vow was an hour and a half each day for creative process. We had a little corner in the old gymnasium (the monastery is a converted elementary school) where we would set up in play. I would make (sonic) patches and we would experiment. We used this combination of the synth, electric, and acoustic instruments that were onsite.

And then every few weeks, we did like the Buddhism style of “crits,” where everyone listens and experiences and then reflects something about their experience—nothing critical at all. And then at the end, you give a final presentation of your work.

SW: I remember people being really moved by it (the song). There was a very stoic priest who had lived at Great Vow for a long time and was a very serious, intense priest, and he cried his eyes out when we performed. I remember him saying, with this tear-soaked face, that it reminded him of what’s possible. That was really touching.

DD: That performance was the 30-minute version, which had a lot more going on, more of an arc, with mood shifts and stuff—a space travel-y journey. Perfect for a bunch of priests, you know? And then when we were making the record, we really trimmed the song down and tightened it up. Basically, we took the middle section and put it into the record.

silent illuminating

SW: In essence, this is a piece about samadhi. It’s kind of like this light is pouring out of you …

DD: … like an exhale …

SW: Yes, exactly. This song was always at the end of our set when we were performing, this exhaling experience of momentary bliss, which can come in waves while sitting in meditation.

We were playing a digitized version of a Persian instrument called the santoor on a MIDI keyboard. It’s kind of dancing around, and there’s a synthesizer that sounds like a whale dancing. This song is trying to emulate this levity, this buoyancy and radiance that can come with this illumination—that can come about during a long period of silence. Suddenly you’re sitting and the sun comes through the window and you feel this enormous sense of peace in the middle of sesshin, and then the next moment, it’s like a hell realm, you know?

DD: And it’s not necessarily silent. My experience of that is that suddenly all of the sounds in my environment are exactly where they should be, and it’s a perfectly harmonized symphony of the air humming through the HVAC system and the birds outside and people clunking around. And it’s all perfect. That’s what this track is alluding to: everything is illuminated.

SW: It’s not like an aural silence. It’s a silence of the spirit, or the ego.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.