A silence has fallen over the wave of self-immolations that engulfed Tibet over the last decade. Few raise the subject in polite circles nowadays.

For Tibetans, it is too painful to contemplate the possibility that 164 of their brethren may have died to advance a cause that appears stalled at best. For others, burning bodies in a distant land do not seem an appropriate topic of conversation at the dinner table or at a cocktail reception. The world has moved on.

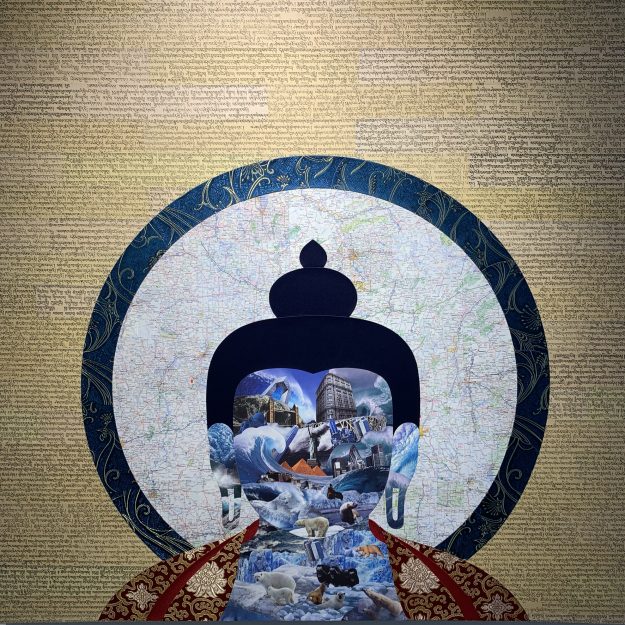

But artist Tenzing Rigdol’s new exhibition, aptly titled My World is in Your Blind Spot (and currently on display at the Tibet House in New York City), breaks this collective silence about the fiery protests of a people on the edge of existence.

In a series of larger-than-life panels that overwhelm the gallery walls, Rigdol’s buddhas sit in repose, radiating the characteristic Buddhist equanimity, while their bodies are slowly consumed—or maybe miraculously unharmed, who knows?—by flames. There is no sense of pain, or alarm, in their expression, only a calm detachment that borders on indifference.

In a recent article, journalist Tracy Ross and anthropologist Carole McGranahan reflect on what happens during a protest by fire. The process is “almost incomprehensible. First, the kerosene or gas poured onto clothing enables ignition. The resulting third-degree burn—the most intense kind, producing charred or whitened skin—can be less painful than milder burns. That’s because the damage is so deep that the nerves die.”

Related: Burning for the Buddha

Are the buddhas in Rigdol’s paintings unperturbed because theirs is a third-degree burn and therefore lost to the senses? The serenity of their poise, so quintessentially Buddhist in its detached pacifism, here seems incongruous, almost cruel.

“Both courageous and tragic, self-immolations challenge us, as witnesses, to either take action or to practice indifference,” Rigdol explains in the exhibition’s program notes. “These acts force us to define and redefine our individual and collective strengths or weaknesses based on our responses. How we respond defines not only myself, but also the world we live in.”

The entire exhibit, curated by Sarah Magnatta, is an unsettling meditation on the Tibetan self-immolations and the world’s response. The burning buddhas—created with a variety of materials including silk, pages of scripture, photographs of fire—clearly represent an indictment of the world’s indifference.

In 2011, Time magazine ranked the Tibetan self-immolations #1 on its list of “Top 10 Underreported Stories.” The following year more than 80 Tibetans set themselves on fire to demand an end to Chinese rule and the return of the 14th Dalai Lama to his ancestral homeland.

The international media’s insufficient reporting on the phenomenon was due, in part, to a paradox: Journalists needed images to print stories about the self-immolations, but images could not be transmitted since Tibet has been under an information blackout. Once in a while someone would, under great risk, smuggle out an image of a self-immolation, but the media outlets would deem the image either “too grainy” to publish, or worse, “too disturbing” to broadcast.

Not all silence can be attributed to the media paradox, though. Sometimes, the silence is simply a result of institutional censorship.

A few years ago, one of New York’s most prestigious museums asked Rigdol to join an exhibition. When he submitted his work, featuring a standing buddha with hints of fire whispering through its body, the curator advised Rigdol to remove the flames because they were too political. The flames, he was told, might offend the sensibilities of the museum’s Chinese patrons.

The museum and the curator, like many institutions, were interested in Tibetan art but not in the Tibetan truth. If the former can be sublime, the latter is just inconvenient.

Rigdol resisted. If he could show his work in an esteemed venue but only at the cost of censoring his message, what was the point? He offered to withdraw from the exhibition. The curator backed down. His ultimatum turned out to be a bluff, and the artwork was accepted.

Rigdol’s work is a protest against private censorship as much as it is a cry against public indifference.

The self-immolations have fundamentally redefined what it means to be Tibetan. The heat of the burning bodies has permeated every aspect of Tibetan life. It is impossible to light a stove, or a cigarette, without thinking of Tapey, Lama Sobha, Thupten Ngodup. One can no longer light an incense stick without seeing the silhouette of Buddhist nun Palden Choetso standing tall in the blazing red flames, before sinking into them.

In a way, My World is in Your Blind Spot is a heartfelt memorial to those who gave up their lives in order to fuel and power a beleaguered people’s long struggle toward freedom. It is a tribute to those who sacrifice themselves for the sake of others. Rigdol’s burning buddhas elevate their sacrifice to the sacred.

The exhibit is on view at the Tibet House through November 14.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.