Alexandra David-Néel lived 100 years. She was born in France in 1868, the period of la belle epoque, and died there in 1969, soon after the student riots in Paris. In between she spent fourteen years studying Buddhism in Asia and, at the age of 55, became the first Western woman to enter the Tibetan city of Lhasa. It is tempting to think that she was born too soon, but so free and bold a female spirit would have encountered obstacles anywhere, at any time. At the age of 16 she was already running away from home for jaunts across Europe, and she traveled to India at 21. Her early adulthood was taken up by a career as an opera singer—ample accomplishment for an ordinary life, but almost overlooked in hers.

It was not until middle age that she married Philippe Néel, the French engineer who supported her through her subsequent adventures, but with whom she almost never lived. Néel did not understand his wife’s interest in Buddhism and the East, but in 1910 he offered her a “long voyage”—he meant something like a year—to “get it out of her system.” She was gone for fourteen years, traveling and living in India, Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Japan, making forays into the forbidden kingdom of Tibet. On her return to Europe, she was celebrated as an adventuress and lived another 45 years as a lecturer and writer. She left four projects unfinished when she died just short of her 101st birthday.

In an age when even those sympathetic to the East were mostly dabblers or lovers of the occult, Alexandra David-Néel distinguished herself both as a scholar and a practitioner. The style of her day was to examine things dispassionately and objectively, but David-Néel experienced them personally and, in such books as My Journey to Lhasa and Magic and Mystery in Tibet, wrote about them the same way.

Alexandra’s father, Louis David, was a French Protestant, a Huguenot, a socialist and a Freemason. He opposed the monarchy of Louis Philippe, participated in the Revolution of 1848, and fled to Belgium with his friend and compatriot, the novelist Victor Hugo. There he fell in love with Alexandrine Borghmans, a devout Roman Catholic who supported the Belgian monarchy and who in many ways was his opposite. They married and eventually moved back to France, and 13 years passed before they had their first child. Mme David was bitterly disappointed that Alexandra was not a boy, and paid almost no attention to her.

“Ever since I was five years old,” David-Néel wrote in My Journey to Lhasa, “I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept. I craved to go beyond the garden gate, to follow the road that passed it by, and to set out for the Unknown. But strangely enough, this ‘Unknown’ fancied by my baby mind always turned out to be a solitary spot where I could sit alone, with no one near.”

At the age of 16—in an era when such behavior was scandalous for a girl—she ran away from her family home in Brussels several times, once to Holland and England, once to Italy, then later through France and Spain. She had taken an interest in religion from an early age, and a schoolgirl friend gave her a review entitled Gnose Supreme (supreme knowledge) published by an English occult society. When she determined at the age of 18 to study English in London, she contacted a Mrs. Morgan at the Society of the Gnose Supreme and arranged to stay there. She spent long hours in the Society’s library, poring over translations of Chinese and Indian texts.

When David-Néel decided to continue her studies in Paris, Mrs. Morgan arranged for her to stay at the Paris branch of the Theosophical Society. Though she found the Theosophical Society not to her taste, she discovered its excellent library, where she first read about Tibetan Buddhism. She also discovered the Musée Guimet, whose Asian collection—renowned to this day—intensified her attraction to the East. One day, believing herself to be alone in the museum, she bowed to a large Japanese statue of the Buddha, and a voice said, “May the blessing of Buddha be with you, Mademoiselle.” That voice turned out to belong to the Comtesse de Breant, who introduced her to other Parisians with an interest in the occult.

By the age of 21 David-Néel had become a devoted linguist, and when she decided to spend a legacy from her godmother on a trip to India, it was in order to pursue her study of Sanskrit. When she returned to Europe penniless, however, she ran head-on into the limitations of her gender. She had begun writing and had published articles on her travels and studies, but they paid little, and a career as a professor was not open to her. She had always shown talent in music—a field that was available to women—so she studied seriously and began a career as an opera singer, returning to the East for a while as the première cantatrice in the Opera Company of Hanoi. During some of this period she lived openly with the Belgian composer Jean Haustont, a fact of which her freethinking father was apparently aware.

David-Néel’s relationship to men was enigmatic throughout her life. Her biographers have variously said that she was repulsed by sex because she didn’t receive enough physical affection as a child and that she detested all things masculine. It is an undeniable fact that when she finally married she spent almost no time with her husband. Yet it is also true that all her spiritual teachers were male, and that the closest thing she ever found to a lifetime companion was a young lama, thought by some to be her lover (although there is no concrete evidence of this), whom she eventually adopted as a son.

It seems possible that she was repelled not by sex or men but by the sexual mores of her culture, in which women functioned as decorative appendages for men, and in which men raised families with their wives but found sexual gratification elsewhere. What David-Néel may really have wanted—even before she knew it—was a spiritual connection with a man, which she didn’t find until she traveled to the East. Her acceptance of marriage before that may have been an attempt to find the financial stability that she needed for her studies. In any case, at the age of 36, she married Philippe Néel, a well-off engineer who, despite his reputation as a philanderer, was considered quite a catch.

The early months of marriage—during which she was often apart from her husband, pursuing her writing career—were difficult. Her letters and journal entries reflect considerable torment about her husband’s wayward past and ambivalence about her role as wife. She was also becoming more and more interested in Buddhism, writing in her diary of “the delicious hour of perfect detachment and intimate joy” when she meditated. Néel, who was somewhat sympathetic to her feelings, offered her the “long voyage” to the East.

Alexandra David-Néel was determined to study religion. At first she returned to India, where she mostly encountered Hindus. She interviewed Sri Aurobindo and the widow of Sri Ramakrishna, and met a Brahman who engaged her in long discussions about religion. She was generally entertained by the wealthy and prominent in India, but disliked the caste system and the misery it engendered. She was interested in the philosophy of Hinduism but never drawn to it as a practice.

It was when she moved to Sikkim that she met three people who were to influence her life profoundly: Sidkeong Tulku, the maharajah of Sikkim; His Holiness the thirteenth Dalai Lama; and the Gomchen (“great meditator”) of Lachen. It was considered unusual – and somewhat bad form – for a Westerner to enter into personal relationships with “natives,” but David-Néel didn’t hesitate, becoming intimate friends with Sidkeong and eventually a disciple of the Gomchen.

This was the beginning of the most important and fulfilling period of David-Néel’s life. She actually underwent a physical transformation, the “neurasthenic,” somewhat unhealthy woman suddenly growing well and looking years younger. Her best biographer in English, Ruth Middleton, speculates that her residence in the Himalayas had much to do with these changes—”Her state of health improved enormously above a certain altitude”—but it also seems significant that David-Néel, who until then had been isolated from other Buddhists, was suddenly living in a place where she received support for her practice. When the Dalai Lama asked her how she could have become a Buddhist without a teacher, she said, “When I adopted the principles of Buddhism, I knew not a single Buddhist, and was perhaps the only Buddhist in Paris.” During their first conversation, the Gomchen of Lachen remarked, “You have seen the ultimate and supreme light. It isn’t in a year or two of meditation that one arrives at the concepts you express.”

In 1912 she wrote a letter to Néel—whom she addressed affectionately as Mouchy—describing her progress: “Each day I find myself further from the illusions and agitations (of the world). A great repose, a great illumination enters into me, or rather, I enter into them. . . . You have a wife who carries your name with dignity. . . . With your support and aid I shall become an author of renown.” Moving to Benares, she spent long hours studying Sanskrit, meditating, and studying with a Vedantist. She had been gone two years and was beginning to see a real conflict between her marriage and her spiritual ideals. Mouchy—understandably—wanted a conventional wife and sexual partner, while she desired a spiritual relationship that he probably wouldn’t even have understood. In fact, though Sidkeong was committed to marrying another woman, she could probably have had that kind of relationship with him, and it would not have been entirely unusual for her to live at the palace in Sikkhim as his friend. Still, the longer she was away from Néel, the more she appreciated his support. “I believe you are the only person in the world for whom I have a feeling of attachment,” she wrote him, “but I am not made for married life.” Increasingly she came to think of solitude as the only way to deepen her practice of Buddhism.

In 1914 she made the decision to move to the summer retreat of the Gomchen of Lachen. This was the famous hermitage at 13,000 feet that she described in Magic and Mystery in Tibet. There she was attended by the 14-year-old Aphur Yongden, who would be her companion for the next 40 years. But during the early months of her retreat she heard of the death of Sidkeong, who had finally taken the throne in Sikkim and may have been poisoned by rivals. She was devastated, as was the Gomchen, who had seen Sidkeong as the only hope for religious reform in Sikkim. The Gomchen had been planning to begin a three-year retreat, but took David-Néel on as a student instead. He told her she must remain “at his complete disposition” for a year, and for once she thought it worthwhile to give up her independence to a man. She spent two years with him in all, studying tantric mysteries and the Tibetan language.

By that time the First World War was raging, and she couldn’t have returned to Néel if she had wanted to (though it is not at all clear that she did). She traveled to Japan in 1917, hoping vaguely that he might join her there and also interested in learning about Zen Buddhism. As the author of Le Bouddhisme du Bouddha (The Buddhism of Buddha), she was welcomed as a celebrity, first in Japan, then in Korea and China. Yongden accompanied her, which effectively meant that his family would disown him and that he had devoted himself to her. It was in China that she met a Westerner who had made the forbidden journey to Lhasa and who told her of his adventures. But civil war broke out in China, forcing her to flee to Mongolia, where she lived in the monastery of Kumbum, the birthplace of the famous Tibetan teacher Tsong-khapa.

David-Néel devotes an entire chapter to Kumbum inMagic and Mystery in Tibet; it was another place—like her mountain hermitage—where she led the life of study and contemplation that she loved. There were some 3,800 lamas there, and she describes the remarkable spectacle of their silent progress to the meditation hall before dawn for the morning chanting. She meditated a great deal at Kumbum and studied in the library, copying the works of Nagarjuna and translating the Prajnaparamita Sutra. She had been away from Europe for ten years, and was beginning to realize that she didn’t want to return until she really explored Tibet. In particular, she wanted to be the first Western woman to enter Lhasa.

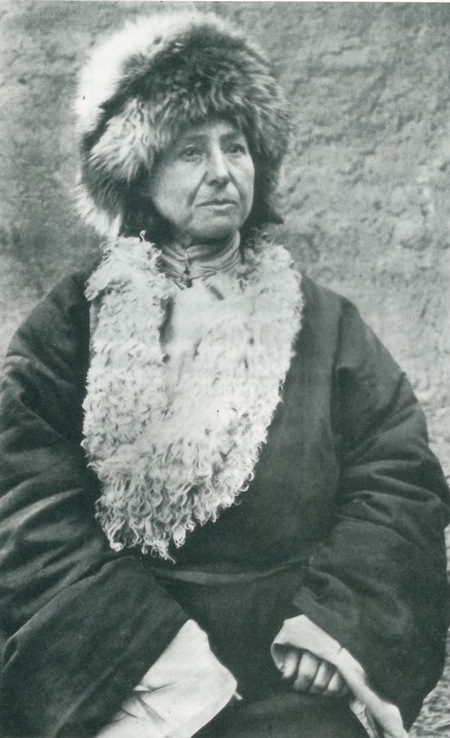

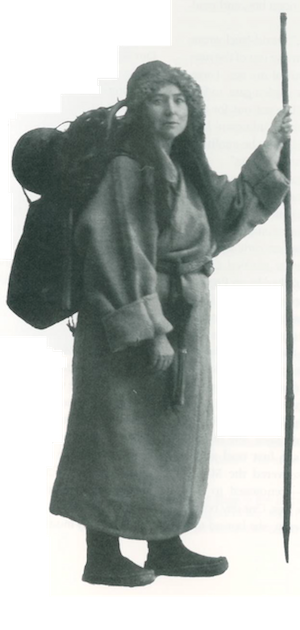

It is this more than any other accomplishment that made David-Néel a famous person, and My Journey to Lhasa is probably her best-known book, read by many people with no interest in Buddhism at all. She and Yongden traveled alone, posing as a lama and his aging mother. She was fluent in Tibetan, familiar with the city they were claiming to have come from, and disguised herself carefully. “She had blackened her brown hair with Chinese ink and ‘lengthened’ it with the aid of a yak’s tail,” Ruth Middleton tells us. “Her already bronzed face and hands she darkened with soot wiped from the bottom of the caldron.”

They journeyed on foot, often at night. There were countless occasions when they barely escaped detection. Once she became stuck halfway across a raging river, suspended by a rope. Twice she and Yongden were accosted by robbers, and she had to fire her pistol to scare them away. They took a treacherous route between two mountain passes, where an untimely snowfall might have left them to starve. As it was, at one point they traveled for days without solid food. By contrast, their arrival in Lhasa, followed by a two-month stay, was anticlimactic. The journey itself was the triumph.

David-Néel’s return to Europe, once that the war was over, was as strange as the rest of her life. The 60-year-old Néel was actually hoping to resume his marriage to Alexandra, but couldn’t understand why she had Yongden in tow, and certainly didn’t see him as an adopted son. Even now that she was back, she couldn’t manage to get together with her husband, so she and Yongden moved to Provence, where she lived as a writer and lecturer, renowned for her exploits. Whatever the nature of her relationship to Yongden, it seems significant that she finally settled down with someone who would be no threat to her independence. Nevertheless, she continued to hope that Néel would join them. When he died finally in 1941, she wrote, “I’ve lost the best of husbands and my only friend”—an odd and rather dubious testimony to her devotion. Even more devastating was Yongden’s death of uremic poisoning in 1955. Fortunately, in 1959 she found Marie-Madeleine Peyronnet, a wonderful secretary who was her companion during the last decade of her life and who maintained a museum in her honor after her death.

To the Tibetans, it seemed perfectly logical for Alexandra David-Néel to have traveled to Lhasa: she was returning to the site of a previous incarnation. From a Western perspective, it seems incredible that she even took an interest in Buddhism in her day, much less that she traveled to the East to study it firsthand. It is further remarkable that she spent so many years as an independent scholar with no institutional support whatsoever.

David-Néel was famous as an adventuress, but that description doesn’t seem adequate to her real accomplishments. She left behind voluminous writings, many of which have not been translated into English, and these are authentic not just because of her scholarship, but because of her lifelong practice. A woman who spent years in a mountain hermitage, who sat in meditation halls with thousands of lamas, who studied languages and scoured libraries for original teachings, who traveled for many years and for thousands of miles to immerse herself in a culture which few people had ever even heard of, writes with far more insight than someone who has only read about such experiences. It is her devotion to Buddhism and her willingness to trace it to its source that are finally most impressive about her life.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.