In June, the Tibetan artist Anay Ngawang Chodak exhibited his work at New York City’s Kate Oh Gallery, marking his first solo show in the United States. “Modern Reflections of Wisdom and Compassion” highlighted Ngawang’s signature motifs, including brightly colored interlocking shapes, blooming lotus flowers, and “happiness pods.” He told Tricycle that these elements are meant to stop viewers in their tracks and encourage them to look within—a fitting practice in bustling Manhattan. “There is a collision of the material world that’s been developed in the West and the inner world that we often forget to look into,” he says. “But they’re both interconnected. If we can connect to the material world and the inner world, we will actually see the harmony that we can create within.”

Born and raised in Kathmandu, Nepal, Anay comes from the family lineage of Repa Dorje Chang, a disciple of the Tibetan mystic Jetsun Milarepa. With a passion for art and spirituality at an early age, he studied traditional thangka—ornate renderings of Tibetan Buddhist deities and historical figures—painting at the Modern Art School in Mussoorie, India, before apprenticing under renowned Newar paubha—the Nepalese equivalent of the thangka—master Roshan Shakya, in Kathmandu, and Tibetan thangka master Ven. Jamyang, in Dharamsala, India. In 2003, Anay was chosen by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Khandro Kunga Bhuma, a realized practitioner and female oracle, to be artist-in-residence at His Holiness’s complex in Dharamsala, where he would spend the next eighteen years.

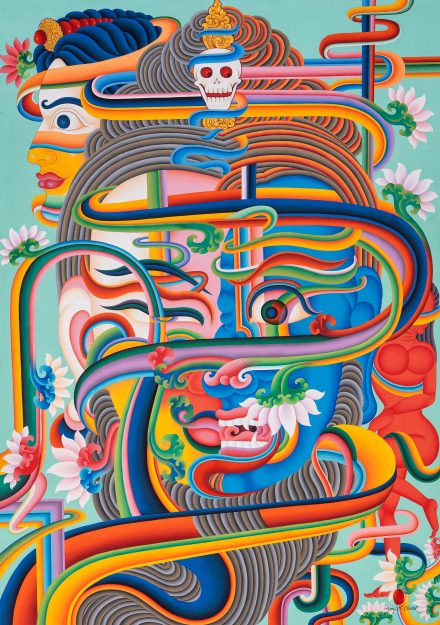

Anay has developed a distinctive painting style marked by traditional Himalayan forms, bold fields of color, and converging abstract patterns.

During his tenure, Anay served as the art director and lead artist for the creation of a series of sprawling thangkas—now installed within the inner sanctum of the five-story Great Stupa in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India—as well as a body of sacred manuscript folio artworks. For Anay, this experience was transformative not only for his technical skills but also for his outlook on art itself. “At the beginning, I thought that art is just art, and it’s nothing more than that,” he says. “But while working on the project, I learned that art is a medium that can be used to improve ourselves inwardly.” With this in mind, Anay left the Dalai Lama’s residence ready to create accessible artwork and share it with the public, thus beginning his career as a modern artist.

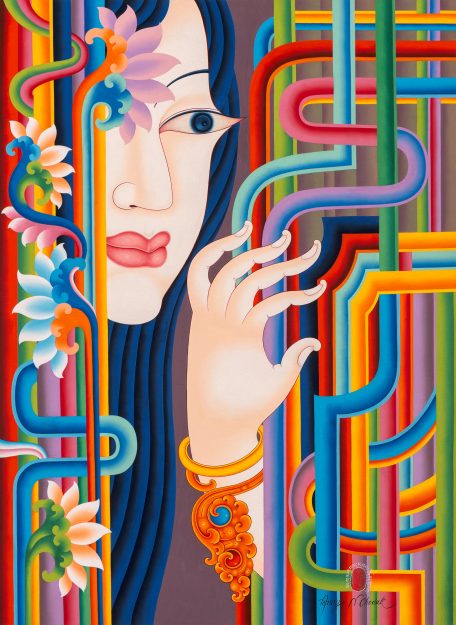

In the years since his departure from Dharamsala, Anay has developed a distinctive painting style marked by traditional Himalayan forms, bold fields of color, and converging abstract patterns. An attempt to follow these luminous pathways around the canvas may induce in the viewer a meditative state, where feelings of compassion and interconnectedness naturally arise. Anay encourages such spaces of reflection, or “investigation.” “I want … viewers to learn and appreciate the human nature that we innately possess, because everything,” he says, “including happiness, comes from the inside.”

“If we can connect to the material world and the inner world, we will actually see the harmony that we can create within.”

To be sure, the blooming faces of Anay’s signature “happiness pods,” seen in Sun, Moon, and Star – Golden Field of Blessings (pp. 70–71), speak directly to our joyous nature. Other pieces, such as the aptly titled Shifting Emotions (p. 73), evoke a wider range of feelings. The beauty of both the background and the leading lady are offset by her noticeably flat affect. Upon close inspection, the viewer sees that her wide eyes are filled with people and objects, hinting at our own complicated inner worlds and encouraging us to recognize this in others.

Anay’s expertise as a thankga master is especially clear in his works that feature the seated Shakyamuni Buddha, as seen on this issue’s cover. An original creation for Tricycle’s Winter 2025 issue, the cover image combines classic elements of Tibetan Buddha depictions with Anay’s signature ornamental flair. He told Tricycle that he wanted to create a painting that “symbolizes timeless Buddhist teachings and the human experience in contemporary times.” Surrounded by bright shapes and lotuses, the serene Buddha in the foreground holds a luminous sphere in his hand. “The sphere is a universal metaphor,”Anay says. “It symbolizes the innate pure nature of every being, reflecting the fundamental qualities embodied by Shakyamuni Buddha.”

Looking ahead, Anay hopes that his art can inspire spiritual growth on “even the smallest scale.” “I pour my soul into the art based on my Buddhist values,” he continues, “so I want to be able to give any type of little joy or happiness to the viewers who see my art.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.