Introduction by Paul E. Brodwin and Roy Richard Grinker

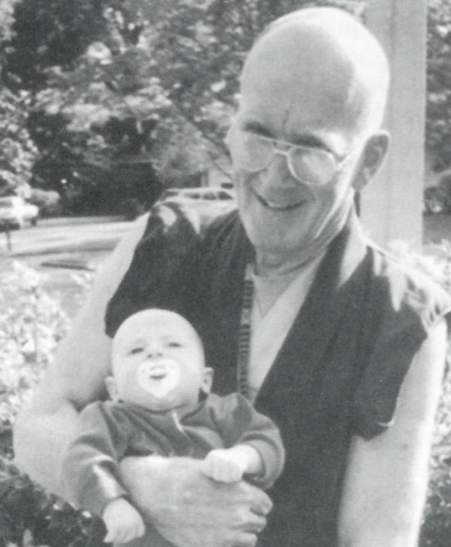

Colin M. Turnbull (1924-1994) was the British-born anthropologist who wrote the best-selling books The Forest People and The Mountain People, humanistic accounts of African societies that have educated generations of Americans about the global threats to indigenous peoples and the cultural riches of the hunter-gatherer way of life. But Turnbull was also an activist—a tireless campaigner against the death penalty and an openly gay man at a time when this carried grave personal and professional risks. Finally, he was a spiritual seeker who ended his life as an ordained Buddhist monk in the Tibetan Gelugpa tradition.

Before his academic studies at Oxford, Turnbull spent two years in India, where he was one of the only Europeans ever to reside in the Brahmin ashram of Sri Anandamayi Ma, one of the most well-known and revered Indian saints and the prototype of the twentieth-century female guru. He also lived for a short time with Sri Aurobindo and his revered wife, the Mother, who eventually founded the international Auroville ashrams. He wrote about his experiences with his Indian gurus in the partly autobiographical The Human Cycle, the title for which was taken from Sri Aurobindo’s own book on life and spirituality. In The Forest People, Turnbull’s classic study of the egalitarian Mbuti Pygmies of the eastern Congo, he thanked Anandamayi Ma for showing him that “the qualities of truth, goodness, and beauty can be found wherever we care to look for them.” After immersing himself in these Hindu traditions, he began his study of Buddhism in 1966 by co-authoring Tibet with Thubten Norbu, the eldest brother of the Dalai Lama.

In May 1989, knowing that he was infected with HIV, Turnbull moved to American Samoa, where he hoped to die quickly and peacefully. But he remained healthy and, at his friend Thubten Norbu’s request, moved to Bloomington, Indiana, to help build the Tibetan Cultural Center, which Norbu had founded. Within a year, he left for Dharamsala, India, where, on April 5, 1992, he was ordained by Lacho Rinpoche Namgyal and given the name Lobsong Rigdol. Three months later he received a Gelong ordination by the Dalai Lama.

Lobsong, as he now called himself, lived at the Nechung Monastery, a renowned Gelugpa center for learning, for six months before returning to Indiana for a brief stay. He and Norbu very quickly had a falling-out, and he returned to Dharamsala. In the winter of 1993, he became ill with pneumonia and was flown to Lancaster County, Virginia, where he had spent much of his life with his lover, Joseph A. Towles, who had died of the AIDS virus in 1988. Turnbull died of AIDS in August and was buried next to his companion.

During his life, Turnbull published very little about his transformative encounter with Buddhism, and certainly nothing as revealing as “An Anthropologist Monk,” printed here for the first time. His reflections on monastic discipline, the spiritual failures of his elite academic training, and the amazingly Buddhist-like lessons he learned from the Pygmies of central Africa make this a unique document for Western students of the dharma and everyone who crosses cultural boundaries and tries to knit together diverse spiritual traditions.

“An Anthropologist Monk,” found on Colin Turnbull’s computer after his death, is one of the last essays he wrote and is published here with the permission of his literary executor. The editors have slightly abridged and amended the original for purposes of clarity. Turnbull’s original usage retained throughout his essay—Ed.

Essay by Colin M. Turnbull

I offer this in full recognition of my own inadequacy, but with love and gratitude to all sentient beings who have been and are my teachers, and who have given me life. I offer it to the monastery of Nechung, which sheltered me while it prepared and instructed me for six wonderful months. If there is any worth in what I have to say, I dedicate it joyfully to all those of the six worlds who, just like myself, are so much in need of the Dharma. We are all Buddha’s children.

As an increasing number of Westerners are studying and taking Holy Orders from Tibetan Buddhists, it seems worthwhile to give some thought to the obstacles they face in understanding and accepting the Dharma. But everyone’s problems and experiences are so different, that what I have to offer here is merely a reflection on my own situation, my problems, and my opportunities, as a social anthropologist who has become a monk.

Leave aside the question of why I became a monk, for there was a whole combination of events, in this life and in previous lives, that led to that opportunity. It was very likely the same combination of events that led me to study anthropology. And happily, Oxford encouraged a humanistic approach. And although I doubt that even they would have used the word “compassion,” they would have understood it. Anyway, when the opportunity presented itself, on retirement, it was a natural outcome of an interest in Buddhism dating back nearly half a century, and of a career of often unconscious involvement in the very issues that concern Tibetan Buddhists the most; issues of life and death, of suffering, of impermanence and uncertainty, of how to love and be a supportive member of a family, yet without attachment. For these are issues that, while they are frequently ignored, or glossed over in our hectic Western lives, are major preoccupations of many of the so-called “primitive” people among whom anthropologists have traditionally worked. They are peoples who all too often prove to be far more “civilized” than we are ever likely to be, at least in terms of the quality and truthfulness of human relationships.

I had not expected the life of a monk to be easy, but the difficulties are not all those that I had expected: the predictable problems of self-discipline and self-control after a long life of relative ease as a householder. At least I knew that I was not becoming a monk as a device that would give me access to information I could use as an anthropologist, an unhappy kind of deceit practiced by too many. But even so, I still had an anthropological mind, and that was my greatest concern.

As an academic I am tired of the mind and the tricks it can play, tired of the insidious ways the mind constantly anchors one in Samsara, tired of a life in which the mind is considered the major if not the only weapon for self-preservation, and yet one that is by itself exceptionally inadequate for spiritual growth and for preservation of the spiritual self.

Not that we can do without the mind, but for Western academics trained to use the mind to the virtual exclusion of the Spirit, we tend either to overplay or underplay its importance. A middle path is not easy to follow after being trained in the scientific method. So in the process of contemplation and meditation, we are plagued with doubts as to whether intellectual analysis should precede meditation or arise from it. We look for a neat, orderly sequence of events, a tidy formula that we can follow, rather than taking each individual case as it comes. Flexibility and adaptability are not common qualities, particularly among the more scientific-minded anthropologists who look for rules and laws that govern human behavior, even their own.

The problem may be the absence of any contact with Spirit in our training. Our literature concerning non-Western religions is full of references to belief (that is, to an intellectual system that we can at least understand, even if we disagree with it), but virtually none to the phenomenon of faith, which is essentially nonrational, if not spiritual.

Yet a Buddhist middle path is just what we anthropologists need in order to avoid the extremes of an exclusively rational science on the one side and a nonrational art on the other. We need both if we are even to begin to comprehend human behavior. And equally, in becoming a monk we have to use all the faculties we have, for becoming a monk is surely more than merely putting on robes and taking a given number of vows and accepting a certain intellectual system of belief. There is an emotional quality in the act that some would describe as spiritual, and it demands an act of faith rather than mere acceptance. For while blind faith may indeed be akin to ignorance, and is to be avoided, there is another kind of faith that raises us, however briefly, above the world of Samsara and above the world of mere reason.

Tranquil Receptivity and Calm Abiding (Zhine/Zhingas) do not come easy to the restless Western academic mind. Yet for the monk, even if we do not achieve them, they are essential tools of the trade, even if they remain at the level of goal or objective. And at the same time, while detaching ourselves from daily concerns we still have to feel compassion and manifest our compassion in action. This is the very antithesis of the philosophy of the pure scientist (if such a thing really exists) who, from the artificial security of his or her ivory tower, believes that in order to be of use one has to have the freedom to be totally removed, emotionally as well as practically, from any semblance of active concern for humanity. Too often academic robes become an excuse for social irresponsibility. It could so easily become the same for the robes of the monk.

Another problem for me as a former anthropologist is the enormous respect many of us develop for the people with whom we live and work. The often repeated reference by Buddhist teachers, whom we also respect, to “barbarians” and “savages” hurts, and smacks of the very ignorance against which we all fight. As anthropologists in the field we find ourselves in that borderland where the difference between the Dharma lived by the people and Buddha Dharma is both slender and questionable. Does it really matter whether or not they know the name of the Buddha Shakyamuni or any of the other Buddhas? Even Buddhists use different terminologies. Surely what matters most is the coincidence of beliefs and practices.

It is these coincidences that impress me. Let me take the example known to me the best, and on the surface an example that would seem the furthest from the most sacred ideals of Buddhism: the Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Forest in central Africa.

To begin with, they are hunters and they live by killing. Yet compassion is central to their lives. They even kill the game that feeds them with compassion, and they have devised a system whereby they never kill more than is absolutely essential to satisfy the needs of the nomadic band. Even more than that, they tell stories of how it is this very act of killing that condemns them and all sentient beings to death. “If only we could learn how to survive without killing,” they say, “perhaps we might live forever.”

And this compassion is manifest in their everyday human relationships, where any form of violence, physical or intellectual, is condemned. This is not to say that there are no such acts of violence, nor that these people are saints, but the ideal is there, and it is constantly and explicitly reaffirmed in their brave and usually successful attempts to avoid all acts of violence. It is plainly evident in family relationships. The concept of blood-brotherhood, while sometimes achieving an effective relationship between individuals, is better seen as achieving an equally effective relationship between groups, the individual always being subordinate to the group. And rites of passage, such as the initiations of boys and girls, far from merely acknowledging the fact that they are growing up, are made an occasion for making a reality of the total values of the society, again downplaying the very perception of individual self, recognizing it as not having any true, ultimate existence.

Above all there is an overwhelming respect for motherhood, so much so that women, as the givers of life, are forbidden from taking part in the actual killing of animals, and the father is sometimes referred to as a “kind of mother.” And any person in any hunting camp will address all those women old enough to be his mother as “mother,” whether there is any biological relationship or not. That may not go as far as recognizing all sentient beings as our mothers, but it is no small step.

Even when it comes to higher flights of Buddhist thought, difficult often for the less educated Buddhist laymen, such as the concepts of impermanence and emptiness, these totally nonliterate hunter-gatherers, in their frequent contemplative moments, are given to talking and singing and dancing about just these kinds of ideas. Their concern is with the phenomenon of life rather than the actual physical entity, be it a human body or a tree. When a human body dies, it is food for the insects. It is left inside its house, built of sticks and leaves, which is pulled down around it and abandoned. The camp moves on elsewhere, leaving the empty body behind.

The Mbuti do not even consider the quality of life as permanent—as continuing some individual existence in the next world, after death. So they could be said not to believe even in the conventional reality of things. Things are temporary, impermanent appearances. Their language is simple and inadequate for the expression in words of the complexity of their thoughts, so they use other means of communication: sounds, music, gestures, and the natural world around them.

Water, in this case, is one such alternative to words. “Look at your reflection in the water,” they told me. “Then if you still think you are the real ‘you,’ touch your other self with your foot. Next put one foot into the other foot. Then as you walk right down into the water, entering your other body, look upwards. Where has that other body gone? And if you walk completely under the water and come out on the far shore, as you come out some other body, just like yours, comes from somewhere and passes through you back into the water. Now who and where is the real self?”

That was perhaps my first lesson in emptiness, from a nonliterate “barbarian” who had never even heard of Buddhism. How can I help but respect him? And indeed, why can’t we learn from him and his uncorrupted wisdom? Just as he has a lot to learn from us, so is the reverse true. I wonder what those people would do, would become, if the Buddha Dharma was translated into their terms. They would certainly recognize it and welcome it with joy.

I may have become a monk, and owe an incalculable debt to the Buddhism of Tibet, hence to the Tibetan people. But having had the opportunity as an anthropologist to live among such people as the Mbuti, so much more advanced in many ways than my own, I cannot help but recognize them also as among my foremost teachers, and to make my prostrations equally to them, in all sincere humility and gratitude.

Lobsong Rigdol (Colin M. Turnbull)

Dharamsala, India 1993

Paul E. Brodwin is associate professor of the Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Roy Richard Grinker is associate professor of the Department of Anthropology, George Washington University. Grinker’s book, In the Artms of Africa: The Life of Colin M. Turnbull, will be published in August 2000 by St. Martin’s Press.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.