On Saturday morning, August 10, 1991, Chawee Borders and her sister Somjit went to the monastery to cook food for monks, the most basic Thai devotional practice. She was late. Approximately 2,500 years ago the Buddha ruled in the Vinaya that monks cannot eat after 11 a.m. As she rushed to the kitchen and began to cook, Chawee noticed the orange-clothed figures lying in a circle on the floor. They were sleeping late, she thought, as she began to cook. Perhaps they were new monks who had arrived late the night before. Then she considered that something else was amiss. She left her sister cooking in the kitchen in order to take a closer look, and she saw that one monk was lying with his body touching the body of a nun, a serious offense according to the Vinaya. Somjit came out and saw the blood. The six monks, a nun, a novice, and a layman were not sleeping but dead—a few hours earlier they had been herded from their beds by grapeshot fired at them, forced to kneel down, and executed by assailants wearing latex gloves. Chawee pulled Somjit, who was screaming, by the arm out of the wat to a neighbor to call the police.

Although Carol Alteneder had lived next to the temple for three years, it took the tragedy to throw Chawee and Somjit into contact with her. In the past she had called the police when she saw the monks working on temple property, mistaking their orange robes for the dress of prisoners from the Arizona penitentiary. Over the next week, Thais would be forced to deal with the world of mainstream Americans who had jostled them and then passed on down the road, with the car radio tuned to a different station.

America had always been strange to them. In America people passed each other on the street and didn’t smile, while in Thailand even people who never met addressed each other by family names—sister, brother, mother, or uncle. They made money and put on weight and also built a temple. They sent to Thailand for monks to live in it. Amid the feast of America, they wanted a Buddhist skeleton present to remind them that deep down all is impermanent, marked by suffering, and empty. Now dazed and terrified, they were too polite to evade the reporters who descended on them and who thought that monks wore gold jewelry or that the gilt concrete statue of the Buddha in the temple was solid gold.

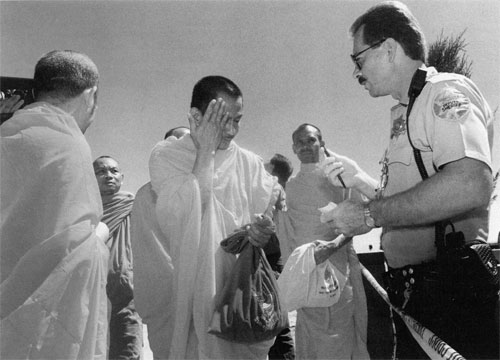

For six days the Thais made the 15-mile journey from downtown Phoenix to the temple in the middle of a cotton field, and for six days they were turned back while the sheriff’s men searched inside for clues. The bodies were taken to the morgue, and it eventually cost the Thai community $30,000 to reclaim them. “In my village when a monk died we put poison herbs in the body’s mouth, and the spirit returned and told the monk who killed him. Here they won’t let us touch the bodies,” said Patrida Hempimarman, a waitress at the Spicy Thai Restaurant.

“I don’t know. I don’t understand. I don’t believe,” said Rattyaporn Phrapatpana, a Thai woman studying for a business degree in Phoenix, in response to the slayings. It was incomprehensible to the Thais that anyone would think to make monks, who are prohibited from holding money by the Vinaya, a target of robbery. On September 13, 1991, the Maricopa County sheriff’s office arrested five men for the crimes. They said the five men, three of whom were later indicted by the grand jury, came from a high-crime neighborhood in Tucson, drove to Phoenix where they bought marijuana and crack, and then ransacked the temple looking for a cache of money. Then, according to the police, they executed the nine people one by one, perhaps to find what they believed were the temple’s treasures or perhaps in anger at not finding any. Before they left, they stole two CD players, a camera, and two rings, and they carved the word blood, the name of the gang, on a piece of temple wall. Some speculated that they had been to the temple before and knew about the $5,900 in temple funds—$900 from community contributions and $5,000 left over from an account to host fifty Thai monks visiting the United States.

The police story was full of holes. The Arizona American Civil Liberties Union accused the sheriff’s office of intimidating confessions out of the men by keeping them in isolation without food, water, or sleep. “It’s the kind of thing that almost becomes a classic of everything you shouldn’t do during an investigation,” remarked Louis Shodes, executive director of the ACLU in Arizona. No physical evidence linking the accused to the murders, only a tip from a resident of a mental hospital who was known as Crazy Mike, whose friends regarded him as a habitual liar and who later denied the statement anyway. The other tip came from two boys who had been stealing watermelons in a nearby field. Supposedly they had kept quiet for thirteen days, because they were afraid of getting in trouble.

In November the Tucson men were released and two others were arrested. Johnathan Doody, 17, and Alex Garcia, 16, were linked to the crime by the physical evidence of rifles. Doody, who was half Thai and whose brother had spent time in Wat Promkhunaram, confessed to planning a robbery and killing the monks and others so there would be “no witnesses.” Their lawyers and family members now say their confessions were coerced as well.

The sudden release deepened the sense of bafflement in the Thai community. “I can’t think of it as a robbery,” said Dr. Sunthorn Plamintr, a well educated monk who flew in from the Buddhidharma Meditation Center in Illinois for the funeral. “As long as we don’t know the motive, the Thais will feel vulnerable.” Whether the actual motive was hatred, self-hatred, or simple greed, the Thais of Arizona felt exposed against the white background of their state. Arizona is white enough that racist groups compare it to Forsythe, the all-white county in Georgia.

They don’t like me because I have dark skin,” said a Laotian immigrant who works in a Thai-Laotian grocery when she is not going to high school. “People give us looks when we stop at intersections in the car. The blonde girls at school think they look perfect, that we’re ugly because we have dark hair. They say things like, “Why don’t you go back to China?”

Earlier in the year, a Chinese church in Phoenix had been defaced with graffiti reading “KKK” and “No Chinks. Go home to China.” In Tucson, a rock had been thrown through the window of the China-Thai Restaurant, and threatening notes had been sent to all three Thai restaurants, saying that someone would kill all the Thai people in town. Anti-Asian crimes were on the rise, and local racist groups like the Liberty Lobby and the Confederate Hammerskins preached their theories that the world-wide Jewish conspiracy was importing Asians to miscegenate with the white race.

In the few days after the murders, restaurants in Phoenix began to receive threats from callers, some with Asian accents, some without. At the Spicy Thai, a woman picked up the telephone on the Wednesday night after the murders. “Are you Thai?” asked the voice on the other end. ” Yes.” “Do you know what happened at the temple?” “Yes.” “You’d better be careful or more of your people will be dead.”

The Maricopa sheriff’s office has discounted the possibility that the murders were a hate crime because no anti-Thai graffiti was left by the killers. It is believed also that the phone threats came from copycats, seizing upon the tense atmosphere created by the murders.

The death of the monks left the Thai Americans isolated from both the living and the dead back in Thailand. Monks perform the rituals that allow the living to help dead relatives. The night before they died the monks had chanted for a Laotian woman named Boua, who had dreamed her mother was wandering in a bad rebirth. Because of their liminal state, monks can contact the dead. Like the yellow leaves that their robes resemble in color, they belong neither to life nor to death but negotiate instead the shadowy and powerful realm between the two. One Thai woman, who asked not to be named, said, “My mother and father are dead. I work seven days a week in a restaurant. Every week I would go to the wat and pray for father and mother and give food. It made me feel good. I never had time to go back to Thailand, and I never saw my mother before she died. Now I have no father, no mother, nothing. I’ve lost everything a second time.”

Beneath Buddhism, in the minds of many Thais, runs a deep vein of belief in the supernatural, fortune-telling, amulets, and spirits. As they met in restaurants to make sense of it all, many Thais discussed the killings in these terms. Fong Miller recalled a dream she had had a week before the slaying. “I went into the living room, and there was nothing in it. It was empty. I knew I would lose something. Something, I thought, not two. I lost my son and my mother. I told Matthew I had had a bad dream. I didn’t know what would happen.” Her son Matthew, a novice, and her mother, Foy, a nun, were among the seven shot that Saturday morning.

Patrida Hempimarman said she believed a former monk, Mr. Somchat, had contacted the murdered abbot during meditation. The abbot, she said, had told Somchat in a vision that the murderers had visited him several times before asking for money, that they were Turkish, and that they were trying to stop the growth of Buddhism in America. However, Mr. Somchat said he had not succeeded in contacting the abbot during meditation. He had had strange dreams, but they were murky, hard to understand. Others had spoken with the other monks at the temple the day before they died, and the monks had said they would see them later. Now they feared their return as ghosts. Although Buddhism condemns personal vengeance, there were those who prayed that a supernatural revenge might fall upon the murderers of the monks. “Every night we pray that the guy who killed the monk will die quickly,” said a Laotian teenager who did not want to be named.

As the week went on, the shattered Thai community regrouped. The brother of the murdered monk, Boonchuey, flew in from Washington, D.C., to handle the floral arrangements in pink, the favorite color of the abbot, and in black, the color of mourning. The Thai ambassador, M. L. Birabhongse Kasemsri, arrived at the Phoenix airport to speak to the governor of Arizona and the sheriff handling the investigations. Buddhist Thai temples around the world flew their flags at half-mast, and those in the United States locked their doors for the first time as well. A thousand dollar reward was offered for information leading to the arrest of the monks’ slayers, and money was raised for funeral expenses. Monks flew in from Los Angeles, New York City, Chicago, and Las Vegas to offer advice: to feel pity for the murderers and their victims instead of anger.

On Friday morning the temple was open, the monks moved in, and a huge tent was erected to shield rows of folding chairs from the relentless sun. Michael Miller and Jerry Hastings, two teenagers, brother and half-brother of Matthew Miller, spoke of the novice who had been killed. Matthew had been young and talkative. He had been born in South Carolina to a Thai woman and an American serviceman, who like many of Phoenix’s Thai-American couples met during the war in Vietnam. Matthew had had a white girlfriend, and together with his brothers had often cruised the malls with the car radio playing rap such as NWA or blues such as Muddy Waters.

When his grandmother Foy arrived from Thailand, she told him stories of a life he had never known, about growing rice by hand, about crocodiles, and poverty so grinding she had had to borrow clothes to go to the temple. Something impelled Matthew to try to live something of his grandmother’s old life at Wat Promkhunaram. He spent hours at the temple learning to meditate, and the monks offered him the chance to ordain for a month as a novice. He shaved his head and took vows to abstain from money, dinner, movies, and sex. The monks taught him that all desire leads to suffering, and he sat observing his mind and plucking desire as it arose like a weed.

The night after he died, Michael and Jerry had meditated in his room, trying to contact their brother’s spirit to learn who had murdered him. They had failed; it was very difficult to clear the mind. On the second day of the funeral they would ordain themselves as novices. They hoped someday to travel to Thailand as monks and to dedicate the resulting merit to their dead brother and their grandmother.

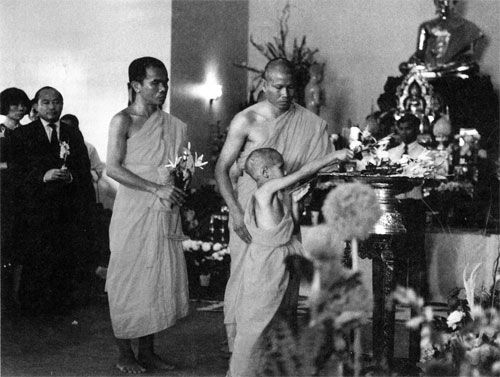

As Michael and Jerry talked, four hearses arrived in the temple parking lot and the monks negotiated the transit of the nine coffins with the funeral directors. The mourners kneeled in the grass to make their bodies lower than the corpses of the monks. A woman started to lament hysterically in Thai. “Whoever killed you, Abbot, was black-hearted! Cruel-hearted! I didn’t think you were dead until I saw for myself! Father, you were so high! You can’t be dead! You can’t be dead!” Photographers crouched between her and the coffin and snapped close-ups of her grief.

One of the monks who flew in to console the community was the abbot of a temple in Los Angeles, a smiling Sri Lankan by the name of Bante Pinyanando. “As human beings, yes, we grieve and lament, but as Buddhists, we are not grieving and lamenting. There is a beautiful story. One time the Buddha in a previous incarnation was killed by a snake. His father, mother, and sister didn’t cry and didn’t lament. Then the Buddha-to-be was reborn as a deity, and so he went to his family and asked, ‘Why didn’t you lament?’ The father answered, ‘A cobra gets a new skin when it loses its skin. My son will get a new life. Why should I lament?’ The mother said, ‘When a pot breaks it cannot keep its same shape. My son cannot keep his same shape. Why should I cry?’ The sister said, ‘In the sky there is a moon. A child can cry for the moon, but it cannot reach it. I can’t get my brother’s life back by crying. Can I get a life back? No. I should see reality.’

“Death is close to us at every moment. Even children in Sri Lanka, when they offer a flower to the Buddha, say, ‘I offer this flower, which is going to die, just as I am going to die, any moment, any time.’ It is not really pessimistic. We are happy people, but we have to look at reality as it is.”

The mourners filed through the chapel of the wat to see the bodies of the monks. Their faces had been reconstructed at the funeral parlor and were heavy with make-up. Then the mourners knelt, palms together in the lotus mudra, while the monks chanted the Abhidhamma, the Buddhist analysis of reality. In the Abhidhamma, reality is something like a movie. All that exists is the present moment and a vibrating array of atoms. Only our delusion and craving form the succession of moments into objects, and into selves. To realize this is to experience nibbana (nirvana), or release from suffering. This is a realization the self rebels against, so the meditation masters of Thailand withdraw to the jungles to subdue their minds. They teach that the closeness of death from tigers and cobras defeats the mind’s natural urge to wander from reality, and fear achieves the goal of a clear, one-pointed mind. Matthew Miller met death in the pleasure garden of America, in a Buddhist temple his people had built so they would never forget Things-As-They Are. Surely in his last moment he did as the forest teachers advise, and focused his awareness on his last breath.

Correction: An earlier version of this article spelled Johnathan Doody’s name incorrectly. The spelling has been updated.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.