Despite ten years of dharma practice and five years of psychotherapy, Leslie was still miserable. To those who knew her casually, she did not seem depressed, but with her close friends and lovers she was impossibly demanding. Subject to brooding rages when she felt the least bit slighted, Leslie had alienated most of the people in her life who had wanted to be close to her. Unable to control her frustration when sensing a rejection, she would withdraw in anger, eat herself sick, and take to her bed. When her therapist recommended that she take the antidepressant Prozac she was insulted, feeling that such an action would violate her Buddhist precepts.

There is a story in the ancient Buddhist texts that relates how the King of Kosala once told the Buddha that unlike disciples of other religious systems who looked haggard, coarse, pale, and emaciated, his disciples appeared to be “joyful and elated, jubilant and exultant, enjoying the spiritual life, with faculties pleased, free from anxiety, serene, peaceful, and living with a gazelle’s mind.” The idea that the Buddha’s teachings ought to be enough to bring about such a delightful mental state continues to be widespread in contemporary Buddhist circles. For many, Buddhist meditation has all of the trappings of an alternative psychotherapy, including the expectation that intensive practice should be enough to turn around any objectionable emotional experience. Yet the unspoken truth is that many experienced dharma students, like Leslie, have found that disabling feelings of depression, agitation, or anxiety persist despite a long commitment to Buddhist practice. This anguish is often compounded by a sense of guilt about such persistence and a sense of failure at not “making it” as a student of the dharma when afflicted in this way. This situation is analogous to that in which a devotee of natural healing is stricken with cancer, despite eating natural foods, exercising, meditating, and taking vitamins and herbs. As Treya Wilber pointed out in an article written before her early death from breast cancer, the idea that we should take responsibility for all of our illnesses has its limits.

“Why did you choose to give yourself cancer?” she reported many of her “New Age” friends asking her, provoking feelings of guilt and recrimination that echo much of what dharma students with depression often feel. More sensitive friends approached her with the slightly less obnoxious question “How are you choosing to use this cancer?” which, in her own words, allowed her to “feel empowered and supported and challenged in a positive way.” With physical illness it is perhaps a bit easier to make this shift; with mental illness one’s identification is often so great that it is extremely difficult to see mental pain as “not I,” as symptomatic of treatable illness rather than evocative of the human condition.

Of course, the First Noble Truth asserts the universality of dukkha, suffering or, in a better translation, pervasive unsatisfactoriness. Is the hopelessness of depression, the pain of anxiety, or the discomfort of dysphoria (mild depression) simply a manifestation of dukkha, or do we do ourselves and the dharma a disservice to expect any kind of mental pain to dissolve once it becomes an object of meditative awareness? The great power of Buddhism lies in its assertion that all of the stuff of the neurotic mind can become fodder for enlightenment, that liberation of the mind is possible without resolution of all of the neuroses. Many Westerners feel an immediate relief in this view. They find they are accepted by their dharma teachers as they are and this attitude of unconditional acceptance and love is one that evokes deep appreciation and gratitude. This is a priceless contribution of Buddhist psychology—it offers the potential of transforming what often becomes a stalemate in psychotherapy, when the neurotic core is exposed but nothing can be done to eradicate it.

Eden’s situation typifies this. A writer whose crisis manifested in her twenty-ninth year, Eden suffered from an oppressive feeling of emptiness or hollowness for much of her adult life. Already a veteran of ten years of intensive psychotherapy, she understood that her feelings of numbness and yearning stemmed from emotional neglect in her youth. Her father, a cold and aloof physician, had avoided the children and retreated to a rarefied intellectual world of scientific research, while her mother was fiercely loving and protective but indiscriminate in her attention, praising Eden for anything and everything and leading her to distrust her mother’s affection altogether. Eden was angry and demanding in her interpersonal relationships, impatient with any perceived flaw, with any inability of her partner to satisfy all of her needs. She had recognized the source of her problem through psychotherapy but had found no relief; she continued to idealize and then devalue her lovers and could not sustain an intimate relationship.

Eden’s inner emptiness was a good example of what the psychoanalyst Michael Balint has called the regret of the basic fault. “The regret or mourning I have in mind is about the unalterable fact of a defect or fault in oneself which, in fact, had cast its shadow over one’s whole life, and the unfortunate effects of which can never fully be made good. Though the fault may heal, its scar will remain forever; that is, some of its effects will always be demonstrable.” No antidepressants were effective in Eden’s case. In order for her to find some relief she had to confront directly her inner feeling of emptiness with the understanding that she was yearning for something that would no longer prove satisfying. Having missed a critical kind of attention relevant only to a child, she found that if someone tried to give her that as an adult, it felt oppressive and suffocating. Only through the tranquil stabilization of meditation could she stand the anxiety of this inner feeling of emptiness without reacting violently against it.

This illustrates the Buddhist approach. A person must find the courage and mental balance to confront the neurotic core or “basic fault” through the discipline of meditative awareness. In the Buddhist view, all of the elements of personality have the potential to become vehicles for enlightenment, all the waves of the mind are but an expression of the ocean of big mind. Mental illness is not an especially developed concept in Buddhist thought, except in an existential sense, where it is exquisitely developed. Buddhist texts speak of the two sicknesses: an internal sickness consisting of a belief in a permanent and eternal self and an external sickness consisting of a grasping for a real object. The focus, in Buddhist psychology, is always on the existential plight of the subjective ego, articulated especially well by Richard De Martino in the classic Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis (1960), co-written with Erich Fromm and D. T. Suzuki:

Object-dependent and object-conditioned, the ego is, further, object-obstructed. In the subjectivity in which it is aware of itself, the ego is at the same time separated and cut off from itself. It can never, as ego, contact, know or have itself in full and genuine individuality. Every such attempt removes it as an ever regressing subject from its own grasp, leaving simply some object semblance of itself. Continually elusive to itself, the ego has itself merely as object. Divided and dissociated in its centeredness, it is beyond its own reach, obstructed, removed and alienated from itself. Just in having itself, it does not have itself.

It is this existential longing for meaning or completed-ness and the inner feelings of emptiness, hollowness, isolation, fear, anxiety, or incompleteness that Buddhist psychology approaches most directly. Depression, as a critical entity, is rarely addressed. The fifty-two mental factors of the Abhidhamma (the psychological texts of traditional Buddhism), for example, list a compendium of afflictive emotions such as greed, hatred, conceit, envy, doubt, worry, restlessness, and avarice, but do not even include sadness except as a kind of unpleasant feeling that can tinge other mental states. Depression is not mentioned.

Mind is described in the traditional Abhidhamma as a sense organ, or “faculty,” like the eye, ear, nose, tongue, or body, that perceives concepts or other mental data, surveys the fields of the other sense organs, and is subject to “obscurations,” veils of afflictive emotions that obscure the mind’s true nature. The faculty of mind and the consciousness produced by it are seen as the primary source of the feeling of “I am” that is then presumed to be real. There is little discussion in Buddhist literature, however, of the mind’s propensity toward disruptions that cannot be remedied through spiritual practice alone. As Buddhism evolved, its emphasis became even more focused on discovering the “true nature” of mind, rather than bothering with discussions of mental illness. This “true nature” is mind revealed as naturally empty, clear, and unimpeded. The thrust of meditation practice became the experience of mind in this natural state.

“Ultimately speaking,” wrote the late Tibetan meditation master Kalu Rinpoche,

the causes of samsara are produced by the mind, and mind is what experiences the consequences. Nothing other than mind makes the universe, and nothing other than mind experiences it. Yet, still ultimately speaking, mind is fundamentally empty, no “thing” in and of itself. To understand that the mind producing and experiencing samsara is nothing real in itself can actually be a source of great relief. If the mind is not fundamentally real, neither are the situations it experiences. By finding the empty nature of mind and letting it rest there, we can find much relief and relaxation amidst the turmoil, confusion, and suffering that constitute the world.

A glimpse of this reality can be quite transformative from a psychotherapeutic point of view, but quite elusive for those who do not have the capacity to let their mind rest in its natural state because of the depths of their anxieties, depressions, or mental imbalances.

Timothy was a successful photographer whose life suddenly unraveled one year. His therapist of four years died unexpectedly of a heart attack, his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer and needed both surgery and chemotherapy, and his dealer suddenly went bankrupt, closed her gallery, and folded without paying him the thousands of dollars that he was owed. His studio felt contaminated by anxious hours on the telephone with his wife and her doctors; he could no longer take refuge there and what was the point, anyway, without a dealer to sell his work? He was immersed in meaninglessness, death, and grief and he began to worry obsessively about his own health. With no active spiritual practice, Timothy lacked a context in which to place the suffering that had suddenly overwhelmed him, no means of being in his pain while still actively living and little ability to be there for his wife’s trauma.

Reluctantly, he went with his wife to a workshop on coping with serious illness by Jon Kabat-Zinn, which generated an interest in Buddhist practice. Slowly, he rediscovered his vitality and took possession of his studio once again while relating to his wife in a way that his un-examined grief had prevented him from doing previously. More than anything else, his dharma practice seemed to give him a method of experiencing mental agony without succumbing to the incredible pain that it produced. His was a situation in which medication would have missed the point. His crisis was an existential or spiritual one as much as a case of unexplored grief; and he was able to find a bit of the relief that Kalu Rinpoche refers to.

The wish that meditation could, by itself, prove to be some kind of panacea for all mental suffering is widespread and certainly understandable. The psychiatrist Roger Walsh remembers an early retreat at which he had the opportunity to watch Ram Dass be with a young man who had become psychotic in the midst of his practice. “Oh, good,” he remembers thinking. “Now I’ll get to see Ram Dass deal with a psychotic person in a spiritual way.” After watching Ram Dass chanting with the young man and trying to center him meditatively, Walsh observed that it was necessary to restrain him because of his increasing agitation and violence. At this point, the young man bit Ram Dass in the stomach, prompting an immediate call for Thorazine, a potent anti-psychotic drug. The desire to avoid medication when doing spiritual practice, to confront the mind in its naked state, is certainly a noble one, but it is not always realistic.

There continues to be a widespread suspicion of pharmacological treatments for mental anguish in dharma circles, a prejudice against using drugs to correct mental imbalance. Just as the cancer patient is urged to take responsibility for something that may be beyond her control, the depressed dharma student is all too often given the message that no pain is too great to be confronted on the zafu, that depression is the equivalent of mental weakness or lassitude, that the problem is in the quality of one’s practice rather than in one’s body. I remember those prejudices from my early psychiatric training. I was quite suspicious of all the psychotropic drugs, equating Lithium with the anti-psychotics like Thorazine which mask or suppress psychotic symptoms but do not correct the underlying schizophrenic condition. One of the only concrete things worth learning in all of those years of training was that there actually are several psychiatric conditions which can be cured or prevented through the use of medications and that denial of such treatment is folly. This is not to say that it is always so clear when a problem is chemical, when it is psychological, or when it is spiritual. There are no blood tests for depression, for example. And yet, the presence of certain constellations of symptoms invariably point to a treatable condition that is unlikely to resolve through spiritual practice alone.

Peggy came to dharma practice in her early twenties while seriously depressed. Adrift in the counterculture, estranged from her divorced, alcoholic, and abusive mother, tenuously bound to her self-involved and indulgent father, she was contemplating suicide when she came upon her first dharma teacher in San Francisco. She felt “found” by that teacher, surrendered the idea of suicide, and threw herself into dharma practice for the next seventeen years. She became gradually disillusioned by a succession of teachers, however, getting to know enough of them personally to lose any ability to idealize them in the way she had originally. When her mother became ill with cancer, a five-year relationship broke up, and her best friend had a baby as Peggy approached her fortieth birthday, she became increasingly withdrawn and agitated. She felt tired and anxious, weak and lethargic but unable to sleep, filled with hateful thoughts and obsessive ruminations, and unable to concentrate on her work or her dharma practice. She took to her bed, lost interest in her friends, and began to imagine that she was already dead. Her friends took her to a spiritual community, to a number of healers, and to several respected Buddhist teachers who finally referred her for psychiatric help. As it turned out, there was a history of depression on her mother’s side of the family. Peggy was convinced she was doomed to repeat her mother’s deterioration; she felt she had failed as a Buddhist and yet was resistant to seeing her depression as a condition that warranted treatment with medication. She got better after about four months of taking antidepressants, which she took for a year and has not needed since. While depressed, she was simply unable to muster the concentration necessary to meditate effectively; the “ultimate view” that Kalu Rinpoche describes was unavailable to her consciousness.

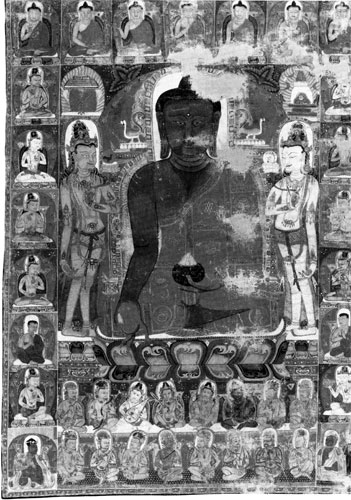

The psychiatric tradition with the most experience in differentiating existential from biological mental illness is probably the Tibetan one, which developed in a culture and society completely immersed in the theory and practice of Buddhism. The Tibetan medical authorities recognize a host of “mental illnesses,” it turns out, for which they recommend pharmaceutical, not meditative, interventions, including many that correspond to Western diagnoses of depression, melancholia, panic, manic-depression, and psychosis. Not only do they not always counsel meditation as a first line of treatment, they also recognize that meditation can often make such conditions worse. Indeed, it is well known that meditation, itself, can provoke a psychiatric condition, an obsessive anxiety state, which is a direct result of trying to force the mind in a rigid and unyielding way to stay on the object of awareness. According to the late Terry Clifford in her book Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry, the Tibetan tradition holds that these medical teachings were expounded by the manifestation of Buddha in the form of Vaidurya in the mystical medicine paradise called Tanatuk, literally, “Pleasing When Looked Upon.” Here Vaidurya is said to have commented that “all people who want to meditate and reach nivana and want health, long life, and happiness should learn the science of medicine.” Treatments for mental illnesses are not antithetical to dharma practice; rather, the Tibetan teachings seem to say, they can be venerated as manifestations of the Medicine Buddha himself.

Yet many of today’s dharma students who suffer from such mental illnesses have trouble identifying effective treatments as manifestations of the Medicine Buddha. They seem to prefer to regard their symptoms as manifestations of the Buddha-mind. A recent patient of mine, for example, was a brilliant conceptual mathematician named Gideon who taught on the graduate level and was a proud, willful, creative man who had gravitated toward Buddhist practice while in graduate school. He had suffered one “nervous breakdown” during that time: for a six-month period he had become restless and agitated with bursts of creative energy, a racing mind in which thoughts tumbled one on top of the next, a labile mood in which laughter and tears were never far from each other, and a profound difficulty in sleeping. He finally “crashed,” spent a week in the hospital, and emerged with no further difficulty for the next five years. He had several depressive episodes in his thirties, during which time he became much less productive in his work, felt sad and withdrawn, and retreated in a kind of uneasy solitude. He was vehemently anti-medication, however, and weathered those depressions by closing himself into his apartment and lying in his darkened room. Again, the episodes passed, and Gideon was able to continue his work. In his forties, he had a succession of episodes, much like the nervous breakdown of his graduate years, in which he also became paranoid, hearing special messages sent to him through the television and radio warning him of a conspiracy. Psychiatric hospitalization was required after he was moved to take cover in Central Park

Gideon’s condition was manic-depression, an episodic mood disturbance that usually first manifests in young adulthood and can cause either recurrent depressions, ecstatic highs, or some combination thereof. It is characteristic of this illness that the episodes come and go, with the person returning to an unaffected state between episodes. Many people with this illness find that the episodes are fully preventable or at least markedly diminished by the daily intake of Lithium salt. Gideon was markedly resistant to the idea that he had this illness, however, and he was equally resistant to the idea of taking Lithium, quoting the dharma to the effect of “letting the mind rest in its natural state” to support his refusal to take medication. The manic episodes came rapidly in Gideon’s forties, hitting him every year or so and effectively ruining his academic career. For a while, his family attempted to put medication in his food without his knowledge, an endeavor which only supported his paranoia, but to this day he has refused to take medication voluntarily. He remains a brilliant and proud man with the ability to work productively between episodes, but the illness has been destabilizing him relentlessly.

Through theses examples I mean to make the point that neither meditation nor medication is uniformly beneficial in every case of mental suffering. Meditation practice can be enormously helpful or can contribute to the force of denial. There is a continuing ignorance in dharma circles of the benefits to be had from psychiatric treatments, just as there is a corresponding ignorance in traditional psychiatric circles of the benefits to be had from meditation practice.

In addition, there is an uncomfortable parallel in the history of psychoanalysis to the current prejudice against pharmacological treatments in dharma circles. Freud’s initial group of followers and adherents were the intellectual radicals of their day. Their excitement and faith in this new and profound method of treatment led them to embrace it as a panacea in much the same way that our contemporary avant-garde has embraced Buddhist practice. The daughter of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Dorothy Burlingham, a seminal New York figure of the early 1900s, for example, left her manic-depressive husband after his relentless and unending series of breakdowns and took her four young children to Vienna in 1925 to seek analysis with Freud. Eventually moving into the apartment below Freud’s, Dorothy Burlingham began a lifelong relationship with the Freud family that evolved into her living with Anna Freud for the rest of her life (she died in 1979). Anna Freud became her children’s analyst, but at least one of them, her son Bob, seems to have inherited the manic-depressive illness from his father. In a tragic story outlined by Ms. Burlingham’s grandson Michael John Burlingham in his book The Last Tiffany, Bob suffered from unmistakable manic and depressive episodes and died an early death at the age of fifty-four. So great was Anna Freud’s belief in psychoanalysis, however, that even when Lithium was discovered as an effective prophylactic treatment, she would not consider its use. He was only permitted treatment that lay within the parameters of Freudian ideology, an approach notoriously ineffective for his condition.

There are undoubtedly dharma practitioners who are depriving themselves in the same way, out of a similar faith in the universality of their ideology. Such people would do well to remember the Buddha’s teachings of the Middle Path, especially his counsel against the search for happiness through self-mortification in different forms of asceticism, which he called “painful, unworthy, and unprofitable.” To suffer from psychiatric illness willfully, when treatment is mercifully available, is but a contemporary ascetic practice. The Buddha himself tried such ascetic practices, but gave them up. His counsel is worth keeping.

Note: All names, identifying characteristics, and other details of the case material in this article have been changed.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.