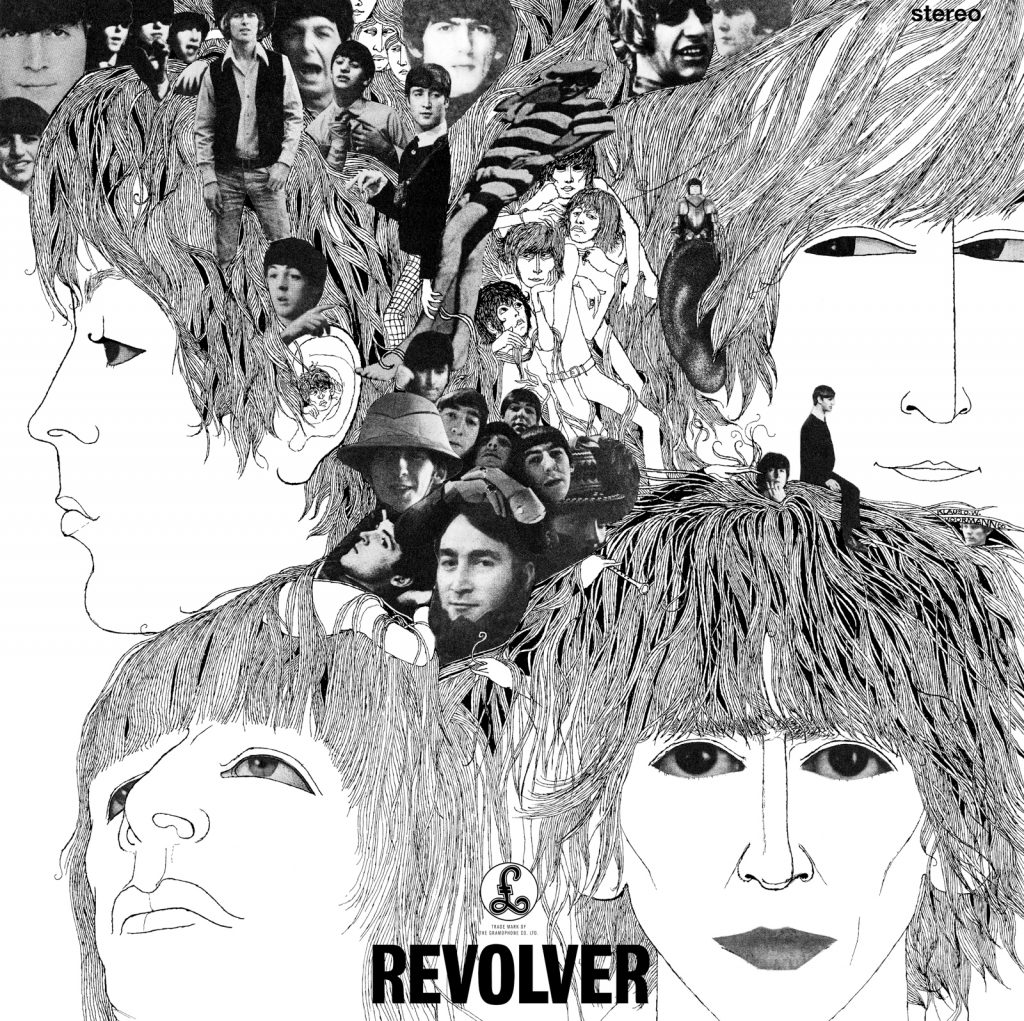

After the Sistine Chapel frescoes were restored in the 1990s, cleansed of nearly five centuries’ worth of soot and candle wax, visitors could at last see Michelangelo’s vivid colors as he had painted them. Since 2006, record producer Giles Martin has been doing something similar for the Beatles tracks originally produced by his father George. He has now remixed Revolver. Its latest incarnation, Revolver: Special Edition, can be streamed, downloaded, or purchased as a deluxe box set that includes a hardbound book by Paul McCartney and either CDs or vinyl discs (so you can still watch it revolve). There are bonus tracks of alternate takes, rehearsal takes, and demo versions, some of which left me gobsmacked—“I’m Only Sleeping” with vibraphone, “Yellow Submarine” as a sad folk song with no submarines. This seems like a good time, then, to strap on our dharma ears and give a fresh listen to what aficionados consider the Beatles’ finest album.

Revolver was born in 1966 of an extraordinary synchronicity. Political liberation and antiwar movements, the sexual and psychedelic revolutions, the opening to Eastern spirituality, even the transformation of fashion from ’50s bland to blazing technicolor, all were reshaping the culture at a dizzying pace. At the same moment, Beatlemania had boiled over into more dangerous forms of hysteria, including assassination threats that ended the group’s touring days forever. Confined to the studio, they would now use the studio itself as an instrument, creating exponentially more complex kinds of music that gave expression to all the new cultural energies. Having become the most popular group in the history of the world—having made it, in John Lennon’s phrase, “to the toppermost of the poppermost”—they could now do whatever they wanted. And they did.

The obscuring grime, as it were, that Giles Martin has removed from the 1966 tracks was a by-product of now-outmoded studio technology. The four-track systems in use at the time were adequate for the simple guitar-driven Merseybeat pop songs like “She Loves You” and “Please Please Me” that the group had recorded just three years earlier. But when, say, the strings of “Eleanor Rigby,” the Motown horns of “Got to Get You Into My Life,” the classical Hindustani ensemble of “Love You To,” and the cosmic soundscape of “Tomorrow Never Knows” were crowded onto those four dinky tracks, it was sonically suffocating.

The breakthrough that has now given them breathing room came, oddly enough, from law enforcement: a new system, driven by machine learning and artificial intelligence, that was developed to isolate the voices of organized crime figures on noisy wiretap recordings. Martin first learned of it when he worked on Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary, where a specialist was brought in to transform the jumble of studio chatter into separate voices. Returning to Abbey Road Studios, Martin had the same specialist capture the individual voices and instruments on his father’s master tapes. Then he cleaned up the tracks, spread them out, and reassembled and rebalanced them in a format that’s as rich as the restored Michelangelo. Now it all pops: the finger snaps you never heard on “Here, There and Everywhere,” the discrete components of Ringo’s drum kit, and—as if they’re right there in the room with you—those gorgeous voices, blended in joyous harmony.

The album’s opening sentence, “Let me tell you how it will be,” is a signal to buckle up and open your ears. George Harrison’s “Taxman” is a protest song, though not one likely to rally the proletarian masses—it’s a sneering lampoon of the steep tax rate that George had to pay as a newly rich rock star. With its cutting satire, its killer Indian-inflected McCartney guitar solo, and its falsetto refrain of “Taxman!” (a droll echo of the Batman TV series theme), it clears the deck for what’s to come: an album unlike anything the Beatles, or anyone else, had done before.

The next track, “Eleanor Rigby,” makes good on that promise. After all the peppy love songs that launched the first wave of Beatlemania, it’s pure existential grimness. Forgoing the first- and second-person discourse that’s essential to the earlier songs (“I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “From Me to You,” etc.), the lyric assumes a third-person bird’s-eye view of the tragic human condition. The happy harmonies give way to Paul’s lone, mournful voice; the ringing guitars are replaced by a string octet’s jabbing, stabbing staccato, directly inspired by Bernard Herrmann’s strings-only score for Psycho. The chorus poses two sweeping, pointedly unanswered questions:

All the lonely people, where do they all come from?

All the lonely people, where do they all belong?

This is not far from the big questions that are the starting point of buddha-dharma. All the suffering beings, where does their grief come from? All the suffering beings, where can they find relief? A clue to the first question is in the repeated word “lonely.” Unlike solitude, which can be delightful, loneliness is the sense of fragmentation, of aching incompleteness that one can feel even in a crowd. It arises from our misidentification as separate, finite selves, chunks of matter lost among a multitude of chunks of matter, each of us too preoccupied with our own unhappiness to care much about the others, till one day we are, like Eleanor Rigby, buried along with our names.

All the suffering beings, where does their grief come from? All the suffering beings, where can they find relief?

After that nadir of despair, subsequent tracks offer some first-draft answers to the second question, the way out of suffering. (Is this a conscious design? I assume not—but that doesn’t mean it’s not there.) In “I’m Only Sleeping,” John rejects what was called, in ’60s parlance, the rat race—the frenzied pursuit of empty goals, “Runnin’ everywhere at such a speed / Till they find there’s no need.” As an alternative, he celebrates the yawning lazy life as a path of freedom, where we paradoxically but effortlessly “float upstream.” Underscored by George’s dreamy backwards guitar solo, it’s in the spirit of the happy Zen hermit-poet Ryokan (1758–1831), who couldn’t even be bothered to fold his legs like a proper monk:

Too lazy to be ambitious,

I let the world take care of itself …

Listening to the night rain on my roof,

I sit comfortably, with both legs stretched out.

–Translated by Stephen Mitchell in The Enlightened Heart

Perhaps the first time most Americans heard a sitar was in “Norwegian Wood,” on 1965’s Rubber Soul, played beginner’s-style by George. Here, just a year later in “Love You To,” he rocks it; accompanied by tabla and tamboura, he winds the song out into a rousing mini-raga, something unprecedented in Western music. Thanks largely to George, raga music was suddenly in the air, and his teacher, Ravi Shankar, became an international superstar. Also suddenly in the air were acid and free love. In contrast to the previous track’s low-key, quasi-monastic approach to liberation, this song takes a hippie-ish, hedonistic, quasi-tantric approach: “Make love all day long / Make love singing songs.” It’s the paisley-streaked vision of enlightenment as a perpetual psychedelic orgasm. Hey, we were young—and for those of us who stuck with it, the vision eventually matured.

In fact, the next track points toward that maturity. When we finally tire of sensation-seeking and addiction to intensity, we have a chance to discover the boundless, all-sufficient ease of just being. Love, by the same token, turns out to be not a mad whirlwind of emotions, but just being … together. “Here, There and Everywhere,” one of the most perfect love songs ever written, beautifully conveys that simple, relaxed intimacy and its transformative power. The song’s introduction declares that I need my love with me … why? “To lead a better life.” Aha. Then, much as meditators find tranquility first in quiet sitting and later wherever they go, this song’s lovers find their shared tranquil sweetness first in the immediacy of here, then there, and finally everywhere.

These themes are supported by lots of tasty musical nuances, like the way “Changing my life with a wave of her hand” ushers in a key change. Taken too literally, lines like “I want her everywhere” can sound like a confession of attachment. But sublime love songs like this one rise (usually unintentionally) to address the real Beloved, which is not a person, shining through the human beloved. And that Beloved we indeed need, and fortunately have—and are—everywhere.

Next up? “Yellow Submarine.” This one’s deceptive. On the surface, it’s a kids’ song with neato sound effects, or a campfire song for potheads—if Ringo can sing it, anyone can sing it. Harmless fun. But it also invites us to go below the surface. Dharma life is all about diving deep, into ourselves, into the unknown. That can be a scary prospect. But if we have teachers and preceptors who’ve gone there before us (“In the town where I was born / Lived a man,” etc.), they can reassure us that this adventure has a happy ending (“So we sailed up to the sun”). But we can’t go it alone. Hence this jolly anthem of sangha solidarity: “We all live … ” And to truly arrive at our destination, we must welcome into this life of ease all sentient beings, without exception: “Every one of us is all we need.”

The last track on Side One is “She Said She Said,” John’s confused-acid-trip song, recounting an incident during a US tour when the band was holed up in a house in Beverly Hills for a few days off. Word got out and they were promptly besieged, with helicopters spying on them and girls coming in through the bathroom window, while they entertained visitors like the Byrds and Peter Fonda. Under these less-than-ideal conditions, John, George, and Ringo took LSD with their guests, and Fonda started unhelpfully showing off his bullet wound from a near-fatal childhood mishap, proclaiming, “I know what it’s like to be dead.” This, my friends, is a recipe for a bad trip. Lennon’s response, though, is a display of intuitive wisdom, signaled by a shift from 4/4 to graceful, easy-swinging waltz time.

I said, No no no, you’re wrong,

When I was a boy everything was right …

In the midst of chaos, that’s a sanity-saving reconnection with the all-OK-ness we knew in childhood: untainted original mind.

Side Two

“Good Day Sunshine,” the Side Two opener, is, like “Yellow Submarine,” deceptive. With its old-timey barrelhouse piano, soft-shoe rhythm, and (literally) sunny lyrics, it seems naively simplistic. But starting from the first chorus, it introduces subtle changes of meter and tonality that sketch out a bigger context, as if to say, “Yeah, I can do complexity. I choose simplicity. I’m in love, it’s a sunny day, and that’s plenty for me, thank you very much.”

“And Your Bird Can Sing”: Lennon dismissed this as one of his “throwaway songs.” Agreed—it’s the album’s weakest track. But arguably it still has dharma overtones, with its talk of having everything you want and seeing the Seven Wonders, yet still being dissatisfied. “For No One,” McCartney’s melancholy breakup narrative—cast, unusually, in the second and third person—may be the only prominent pop song with a featured French horn solo. It’s a poignant piece, but to some ears Paul’s upper-register singing here is painfully saccharine. “Dr. Robert,” John’s ode to a notorious New York physician who supplied speed-laced “vitamin” shots to celebrity clients, reminds us that not all the chemical exploration of the ’60s was aimed at consciousness expansion. Moving right along…

As it fades in from the silence, the syncopated guitar hook that introduces “I Want to Tell You” feels like some sort of luminous beacon signal, calling to us from distant skies. Harrison’s brilliant last song on the album, it stands in ironic contrast to his first, with the taxman’s confident “Let me tell you.” It’s easy to be that confident when you’re thoroughly square, when all you know is the rule book. Here the rule book has melted; having turned on, tuned in, and dropped out of the square world, George has gone into free fall. But he makes the rookie mistake of trying to explain it to someone who isn’t experiencing it—maybe a friend, a lover, or, for the Beatles in 1966, the teenybopper fan base that were scratching their heads over the band’s new direction.

Explaining never works: “All those words, they seem to slip away.” The song powerfully conveys the sensation of cycling through multiple planes of consciousness and, each time we touch down on the earth plane, stammering in wordless frustration. And then off we go again: “I’ll make you maybe next time around.” The frustration is rendered emphatic by the queasy, dissonant piano chord banged out in insistent quarter notes. But by the end, we find resolution in the wisdom that such cosmic voyaging finally achieves:

I don’t mind,

I could wait forever, I’ve got time.

If I’ve really seen transcendent eternity, there’s no more urgency, no hurry to make those who are still stuck on the earth plane understand what I’ve seen. As I reach in from vast timelessness, I’ve got time … in the palm of my hand. And then: OK, see you later, that luminous beacon (the guitar hook, reprised in the outro) is calling me back skyward, fading to silence, as Paul unwinds the word “time” into curlicues of Indian-style melisma. Wow.

This is wisdom. In Ram Dass’s seminal book Be Here Now, there’s a hilarious illustration of a barefoot hippie, arms waving in the air, running frantically up the aisle of a church, yelling to the square congregation, “Listen to those words you’re singing!! It’s really here! They’re all true!” Ram Dass notes wryly, “Don’t be psychotic: Watch it. Watch it.” The lyric does get one thing wrong, though: “It’s only me, it’s not my mind / That is confusing things.” Of course it should be, “It isn’t me, it’s just my mind.” (After years of being bugged by this, I at last found a passage in George’s 1980 book I, Me, Mine where he says exactly the same thing. Thank you.)

“Got to Get You into My Life” is Paul’s exuberant love letter to a new state of consciousness, “Another road where maybe I / Could see another kind of mind there.” By his own account, the object of his affection was marijuana, but the song, like all true art, transcends the circumstances of its creation. It applies to us now, when a text or a teacher reveals an exciting new vista, or we come out of a sitting session with the delicious, empty openness of existence at last radiantly clear. And then: I’ve got to get this into my life, to be no longer a tourist but a resident, “Every single day.” Ignited by that prospect, and urged on by the wailing horns, Paul’s singing here is irresistibly joyous, rising above his tendencies to sound cloying when he’s sweet and lightweight when he tries to rock. Here he reaches an apotheosis of rocking sweetness.

And finally, Mount Everest: “Tomorrow Never Knows.” How revolutionary was this three-minute epic? Let us count the ways. It’s the first known pop song with no rhyme. The first with no chord changes. (Despite repeated teasing flirtations with B-flat, it never leaves the key of C.) First to use sampling, first to use backward loops. And it’s rock’s first great foray into buddhadharma, by way of psychedelia.

The lyric was inspired by John’s reading of The Psychedelic Experience, adapted from the Bardo Thödol, the so-called Tibetan Book of the Dead, by the Harvard psychonauts Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner. Leary and company had realized that the traditional Tibetan guidance for enlightened dying also worked for the “ego death” accessed through psychedelics—and that the lack of that very guidance was what led to the panic that precipitated bad trips. The song’s opening lines, “Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream,” lifted directly from the book, arrived on the airwaves just in time to help a whole lot of inexperienced trippers cool out. (But again, I have to quibble with a line about the mind. After 50-plus years of teaching meditation and seeing people struggle to turn off their minds, I would change it to “Ignore your mind.”)

It’s rock’s first great foray into buddhadharma, by way of psychedelia.

John famously told George Martin that he wanted to sound like the Dalai Lama calling down from a mountaintop. (Everest indeed.) This effect is achieved in the last verse by filtering his voice through a Leslie speaker cabinet, normally used for a Hammond organ. The ineluctable pull into the Beyond (“Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void”) is enacted musically by the constant drone of George’s sitar and tamboura, by backwards guitar licks that sound like time being sucked down the bathtub drain, and by Ringo’s propulsive drumming. His syncopated kick-and-snare pattern is the lone staccato element, relentlessly pushing us forward through a legato sea. With his usual thematic precision, he uses a conventional snare backbeat in the first half of each measure, only to blow things open in the second half with an out-of-left-field syncopation. Expected/unexpected, solidity/space, form/emptiness, again and again and again.

The most striking sonic element is the tape loops—sixteen of them in all, each just a few seconds long—of various distorted Eastern and Western instruments, played forwards or backwards, slow or fast. The mysterious “seagull” sound is Paul’s laugh, sped up. In those predigital days, all of this had to be put together by hand and in real time, with technicians stationed throughout the Abbey Road building, running loops of physical tape around pencils to maintain their tension, and all four Beatles at the recording console, working the faders.

The most mind-blowing words of this mind-blowing album are its very last. They start by counseling us to perform our role in the samsara-movie all the way through (“play the game Existence to the end … ”), then invite us into the space beyond the movie.

… Of the beginning

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

That’s not your standard rock ’n’ roll repeat-and-fade ending. It’s not repetition at all. Like a friend of a friend or the crème de la crème, it’s the beginning of the beginning of the beginning of the beginning, and on and on and on and on, spiraling into infinite regress: all of birth and death and birth and death, all of world and void and world and void, all pinwheeling away and away and in and in and in.

That flipped my lid right open when I first heard it in 1966, and it still does today. Thanks for playing, guys.

♦

This article was originally published online here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.