Ernest Hemingway spoke once of sitting at his desk each morning to face “the horror of a blank sheet of paper.” He found himself (as any writer can confirm) having to produce by the end of the day a series of words arranged in a way that has never before been imagined. You sit there, alone, hovering on the cusp between nothing and something. This is not a blank, stale nothing; it is an awesome nothing charged with unrealized potential. And the hovering is the kind that can fill you with dread. Rearrangement of the items on your desk assumes an irresistible attraction.

I was once reminded of Hemingway’s phrase while poised to write an essay after the completion of a meditation retreat in a Korean Zen monastery. Hovering on the cusp between nothing and something at my desk was not at all dissimilar from sitting on a cushion in an empty room asking myself, “What is this?” Such meditation requires that you rest in a state of perplexity about “the great matter of birth and death,” hovering, as it were, in an abyss of unknowing. You still the mind, ask the question, listen and wait. Like Hemingway’s “blank sheet,” this too can give rise to dread. But with no objects at hand, no books on any shelf, the mind flees its predicament by erupting into an orgy of distraction, or by lapsing into sleep.

The artist’s dilemma and the meditator’s are, in a deep sense, equivalent. Both are repeatedly willing to confront an unknown and to risk a response that they cannot predict or control. Both are disciplined in skills that allow them to remain focused on their task and to express their response in a way that will illuminate the dilemma they share with others.

And both are liable to similar outcomes. The artist’s work is prone to be derivative, a variation on the style of a great master or established school. The meditator’s response might tend to he dogmatic, a variation on the words of a hallowed tradition or revered teacher. There is nothing wrong with such responses. But we recognize their secondary nature, their failure to reach the peaks of primary imaginative creation. Great Art and Great Dharma both give rise to something that has never quite been imagined before. Artist and meditator alike ultimately aspire to an original creative act.

The primary imaginative act in the Buddhist tradition occurred when Gautama Buddha addressed the five ascetics in the Deer Park at Sarnath and “set in motion the wheel of Dharma.” It was here, rather than at the moment of awakening itself, that the Buddha expressed an original response to the dilemma he shared with others. His originality lay with the conception of the Four Noble Truths (i.e., anguish, its origins, the cessation of its origins, and the path leading to such cessation), which set the template for all subsequent Buddhist thought. Since that moment, for any human endeavor to be “Buddhist”—whether in psychology, philosophy, or aesthetics—it needs to fit in that template.

According to early tradition, the awakening left the Buddha in a stunned silence. He saw the benighted world as incapable of understanding what he had experienced, and sat there serenely poised on the edge of Nirvana. But is this not just a way of saying that he was at that time still incapable of imagining how to express his experience? If so, it would also confirm the doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism that “Buddhahood” is fully realized not at the moment of awakening, but only when the awakened imagination begins to creatively emanate images.

While widely accepted, this “lost weekend” account of the gap between the Buddha’s awakening and his subsequent teaching career is awkward. An alternative version portrays the awakening as triggering a veritable explosion of the imagination. The opening passage of the Avatamsaka Sutra, a vast compendium much loved in East Asia, reads:

At one time the Buddha was in the land of Magadha, in a state of purity, at the site of awakening, having just realized true awareness. The ground was solid and firm, made of diamond, adorned with exquisite jewel disks and myriad precious flowers, with pure clear crystals. The ocean of various colors appeared over an infinite extent. There were banners of precious stones, constantly emitting light and beautiful sounds. Nets of myriad gems and garlands of exquisitely scented flowers hung all around. The finest jewels appeared spontaneously, showering innumerable gems and flowers all over the earth. There were rows of jeweled trees, their branches and foliage lustrous and luxuriant. By the Buddha’s spiritual power, he caused all the adornments of his awakening to be reflected therein.

The sixth-century monk Chih-i, founder of the syncretic T’ien-t’ai school of Chinese Buddhism, regarded the Avatamsaka, delivered in the first three weeks after the Buddha’s awakening, as a spontaneous poetic outpouring of enlightenment intelligible only to “gods.” Realizing that its imagery was inaccessible for the people of his time, the Buddha left Bodh Gaya for Sarnath, where he embarked on the next phase of his teaching. In so doing, he was moved to engage with the anguish of human beings and thereby enter into history.

“Few men,” J. W. N. Sullivan wrote in 1927, “have the capacity fully to realize suffering as one of the great structural lines of human life.” Interestingly enough, he was speaking not of Buddha, but of Beethoven.

Bach escaped the problem with his religious scheme. Wagner, on the basis of a sentimental philosophy, finds the reason and anodyne of suffering in the pity it awakens. Mozart, with his truer instinct, is bewildered. To Beethoven the character of life as suffering became a fundamental part of his outlook. . . . Suffering is accepted as a necessary condition of life, as an illuminating power.

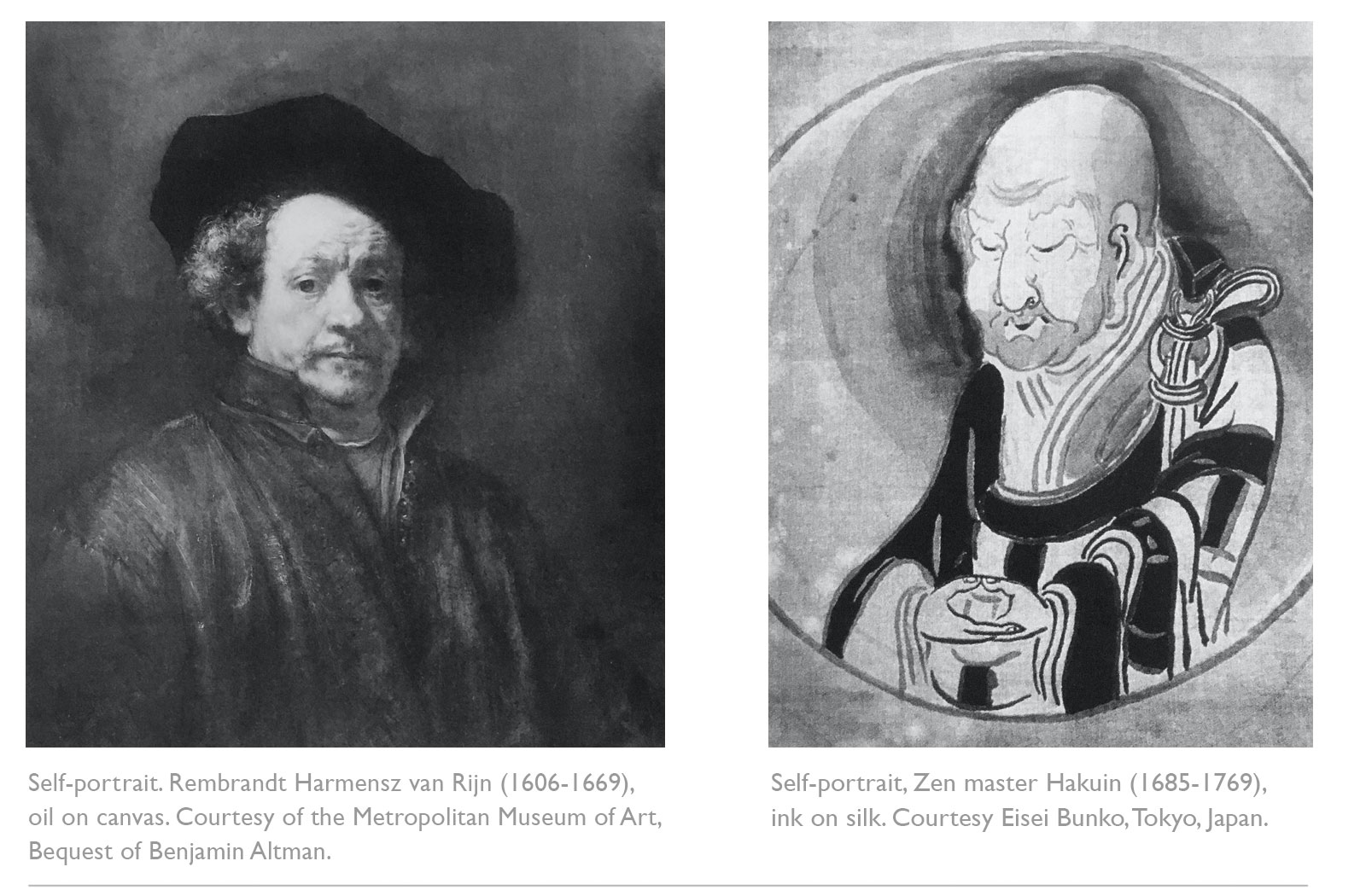

As with Great Dharma, Great Art begins with an unflinching acceptance of anguish as the primary truth of human experience. A self-portrait by Rembrandt or one by Zen master Hakuin, a fragmentary piano sonata by Schubert or an adagio from a late Beethoven quartet, a haiku by Basho or a verse by Eliot: all are united by the terrible beauty of anguish. They are also held together by a vivid stillness of mind, what Sullivan calls “a serenity which contains within itself the deepest and most unforgettable sorrow, and yet a sorrow which is transformed by its inclusion in that serenity.” Thus does a work of art come to “fit the template” of the Four Noble Truths.

There is no reason why a Buddhist should not profoundly value works of art that are not intentionally Buddhist. For if a work of any tradition heightens awareness of the three signs of existence (change, anguish, transparency), it will serve the fundamental tasks of Buddhism: to fully know anguish, to let go of self-centered craving, to realize cessation, and to cultivate the path.

Like Great Dharma, Great Art begins in anguish. It is through knowing anguish, rather than evading or ignoring it, that the door to beauty is first opened. Basho’s aching words:

Departing spring!

Birds crying;

Tears in the eyes of fish.

are illuminated by T.S. Eliot’s

. . . notion of some infinitely gentle

Infinitely suffering thing.

Contemplative experience is not merely cognitive and affective but aesthetic.

***

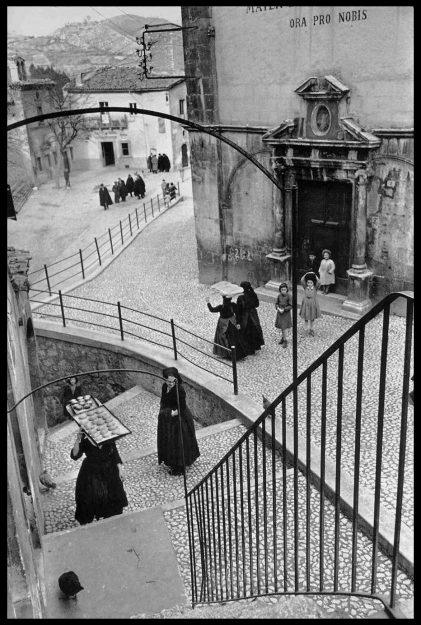

In a confined, opaque world given to the ephemeral gratification of desire, we merely skim the surface of things. We rarely stop long enough to pay attention to anything. “It takes an artist to make us attend to the message of reality,” wrote E. H. Gombrich of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the photographer who once described his art as “holding one’s breath when all faculties converge in the face of fleeing reality. . . . It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.” A meditator who articulates his vision of such moments also makes us “attend to the message of reality.” And he does so most effectively when he finds his own voice. “It is a way of shouting,” says Cartier-Bresson of photography, “of freeing oneself, not of proving or asserting one’s originality.”

The pivotal moments in the history of Buddhism have been defined by comparable instances of Great Dharma. Each has been marked by an original creative act in which the dharma has been reimagined in a way appropriate to the prevailing circumstances. These moments have occurred each time political, social, or religious conditions have shifted and, above all, whenever Buddhism has crossed into another culture.

The historical visionaries of Buddhism have all arisen in response to such challenges. The greatness of Nagarjuna, Hui-neng, Shantideva, Padmasambhava, Milarepa, Dogen, Tsongkhapa, and Hakuin (among others) lay in their capacity to imagine something that had never quite been imagined before. While the imagination found its raw materials in tradition, it transformed them through wisdom and compassion, and was further enabled by literary, poetic, or rhetorical skills.

Yet, as far as I am aware, there is no term in any of the classical Buddhist languages that corresponds to the English “creative imagination.” I can think of no doctrine that actively celebrates it. Moreover, such a notion is at odds with the conservatism of traditional Buddhist institutions. Like those of all religions, these institutions maintain their power by controlling the imagination. By explicitly and implicitly decreeing what can and cannot be imagined, they not only dictate the moral framework of punishment and reward, but also constrain the free and creative urges of the individual. Not surprisingly, the greater an institution’s political and social power, the more clerical and repressive it becomes.

Without exception, moments of Great Dharma have been followed by periods of dogmatic ossification, in which preservation of the outer forms of a great teacher’s legacy has suppressed the creative impulse that inspired him. Given the generally inert, isolationist, and autocratic character of premodern Asian societies, these periods of ossification have sometimes lasted centuries. To offer a fresh, imaginative vision became seen as a threat to an established hierarchy of power.

Even when the imagination is used in traditional practice, as in Tibetan Buddhist tantra, it rarely goes beyond the affirmation of a symbolic or archetypal truth. Each practitioner is instructed to identify with and visualize in painstaking detail exactly the same god with precisely the same attributes. In some traditions, one must promise to recite the form without variation every day until one dies. Failure to do so, one is warned, will result in birch in the excruciating Vajra hell. The imagination is dangerous and subversive. If it is to be used at all, then it must be strictly controlled.

Historically, such ossification of religious structures has been periodically rejected by a resurgence of the creative dimension of Buddhist practice. In Buddhism, the two most striking instances of such movements are those of the mahasiddhas, the eccentric tantric adepts of India, and their almost exact contemporaries in China, the iconoclastic T’ang dynasty Ch’an (Zen) masters. Both of these groups, celebrants of the free imagination, rebelled against the suffocating clericalism of the times and initiated ways of life provocatively at odds with the established religion. Yet the conservatism and autocratic nature of their respective cultures allowed them to flourish only for relatively short periods of history before they became either marginalized or normalized through reincorporation into a renewed clerical orthodoxy.

The technological paradigm that dominates modern culture easily leads to the assumption that Buddhist practice is a set of spiritual techniques aimed at successfully solving the problem of anguish. While there clearly is a technical dimension to Buddhist practice, this is no different from the technical skill of an artist or writer. What matters in the creation of a work of art is the capacity to place that skill in the service of the imagination. The same is true of dharma. No matter how accomplished one’s technical proficiency in meditation (for example) may be, such skill in itself can lead to no more than becoming an expert: a master craftsman as opposed to an artist.

In fact, the practice of dharma is more truly akin to the practice of art. With the tools of ethics, meditation, and understanding, one works the clay of one’s confined and anguished existence into a bodhisattva. Practice is a process of self-creation.

In a pluralistic and agnostic culture, might there not emerge a way of Buddhist practice founded on a democracy of the imagination? While it would be naive to assume that clerical institutions could vanish overnight (or even that this would be desirable), the conditions of life are such today that a more resilient alternative can certainly be imagined, whether it can be realized or not.

In sharp contrast to their medieval predecessors, modern societies are frenetic, pluralistic, and individualistic. As the dharma seeks ways to respond to their anguish, may they not in turn transform Buddhism in ways hitherto unimagined? Rather than remaining the discrete preserve of the rare spiritual genius, might creative imagination not be released into the hands of every practitioner? Could we not envisage a democracy of the imagination, in which each individual ceases to be a passive recipient of spiritual truths and becomes instead their active creator?

Both the artist and the meditator are repeatedly willing to confront an unknown, to risk a response they cannot predict . . .Buddhism is often criticized for regarding the world as an illusion. Such criticism, however, is founded on a misunderstanding. Buddhism says not that the world is an illusion, but that it is like an illusion, thus highlighting the crucial distinction between a literal and a metaphoric truth.

And not just any old illusion. The term specifically refers to the kind of theatrical illusion a magician in ancient India would produce for an audience. The texts describe how such illusions are the product of a variety of conditions: occult substances, spells, and the magician’s hypnotic power. The resultant illusion, say, of a dancing horse, only arises in dependence upon these conditions. Although a horse appears to be there, under closer scrutiny it would be exposed as a magical illusion rather than a flesh-and-blood animal. Only because of the audience’s credulity does the illusion seem to be something other than it is. We do not have to believe in magic spells for this to work. We only have to be able to enjoy a film. The same elements are at work: cinematic technology, suspension of disbelief, the director’s skill in organizing a compelling narrative. The result is the same.

Life, too, is like this. What appears to us through the senses seems real and solid enough, but once we submit it to deeper scrutiny (whether through physics, postmodern philosophy, or Buddhist meditation), that out-thereness-in-its-own-right of the thing starts to dissolve. Once we notice its utter contingency, the gut feeling that there must be something solid and unchanging at its core weakens. The thing is not only seen to emerge from a complex set of causes and conditions, but also to depend on a vast number of parts, attributes, and components. If we look closer still, we find that it is what it is because of the way we talk and think about it, because of the peculiar way in which our culture perceptually organizes it so that it makes sense. Nothing else, no extra metaphysical essence, is necessary. While language forces us to use the word it, ultimately there is nothing to which it refers.

Life is like a movie. It is like an unfolding story that we read and interpret, while identifying with the stars (i.e., gods) and immersing ourselves in the drama. When we start to notice this, life becomes lighter. The monotony fades and the magic begins. For when we turn our attention to our bodies, feelings, perceptions, impulses, and consciousness, we find that we are woven of the quixotic threads of ongoing stories. For only such a self can create and be created. A fixed, intractable one is as good as dead.

In the individuated culture of the West, spiritual inspiration and meaning are found less in static icons and religious archetypes and more in the unfolding dramas of theater, music, novels, and films. We find our heroes and heroines not in timeless icons but in flesh-and-blood characters forging themselves from the tensions of real and fictional dramas. A democracy of the imagination is one in which the stories of the gods (myths) are brought down to earth and incarnated through individuated narratives. Not only might it free the creative impulses of the individual but also of communities to envision afresh how they might tell the story of their own unfolding.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.