Things have changed since the mid-1970s, when I began to study and practice both hatha yoga and Zen Buddhism. Back then, it was common to be told by Zen teachers that all one needed to do was to sit. Zazen was the be-all and end-all of practice, and if one practiced assiduously enough, nothing else was needed—not therapy, not text study, and most certainly not yoga! Despite the ruin of many a good knee, most teachers were pretty firm in this blanket condemnation. To many at the zendo where I practiced, yogis were bliss-heads, caught in denial of dukkha—the existence of suffering—and they looked askance at my dedication to my twice-weekly hatha yoga classes.

Meanwhile, at the ashram where I took yoga classes, I was repeatedly told that yoga was a complete spiritual discipline, and that the practice of asana (postures) was preparatory to meditation practice. But we never seemed to get to actually meditating in class. As for my interest in Zen Buddhism, as far as those yogis were concerned, there could be a no more dour, joyless, miserable lot than Zen students, sitting stock-still in the severe and colorless zendo, all obsessed with suffering.

Yet right from the start I intuitively knew—and confirmed from my own experience—that these two practices had much to offer each other. And, in fact, over the past three decades, many Buddhist meditators (including Zen students) have been drawn to hatha yoga for the ease and strength it can bring to the body, while many yoga students have turned to Buddhist meditation for the deepening of awareness, insight, and equanimity it can cultivate.

While this complementary approach has much to offer, I have found that a deeper, more integrated, comprehensive approach is possible—and may even be necessary —if one truly wishes to practice yoga holistically. The complementary approach still looks at yoga and Buddhism as different, with the difference being that yoga is understood to be about the body, and Buddhism (and meditation in general) about the mind. A deeper investigation of just what is happening when we practice will quickly reveal the inaccuracy of such a view. When we sit in meditation, much of the “work” is related to how we experience the body, and how we react to that experience. And when we are practicing the asanas of hatha yoga, our minds tend to constantly run commentary, react with story lines and judgments, wander from what we are doing, lean toward the future and away from the past, grasp the pleasant and push away the unpleasant—just exactly what they do when we sit in meditation!

So while things have changed since the seventies, it seems to me they haven’t changed enough. The primary cause of the false distinction between yoga and Buddha-dharma is the historical anomaly that it was the physical aspect of hatha yoga, the asanas, that first caught the attention of Western students. For many people, the great diversity of the yoga tradition was reduced to the mere physical performance of the postures and movements of hatha yoga. But the Sanskrit word yoga, meaning “union,” derives from a verbal root, yuj, “to yoke,” as we do when we restrain our attention from wandering when we sit in meditation. From the very beginning, the prime activity of the yogi was to sit in meditation. The posture one takes in sitting meditation is the fundamental asana, and is described by the sage Patanjali (second century B.C.E)—in his Yoga Sutra, the foundational text of classical yoga—as that posture which is both stable and easeful.

While the asanas of hatha yoga are what most Westerners are familiar with as yoga, the truth is that such postures were developed rather late in the history of the yogic tradition. For most of yoga’s history, meditation, chanting, selfless service, and study were the main practices of yogis and yoginis. As I tell the retreatants at Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, where I teach asana, this broader understanding of yoga and asana makes it clear that whenever one takes her seat in the zendo, she is practicing yoga.

The word yoga as “union” refers to the integration of body, breath, and mind, and to the dissolution of the sense of separation between the “self ” as subject of experience and the “other” as object of experience. Whenever this state of embodied integration manifests—whether one is sitting, walking, cutting carrots, or changing diapers—there is yoga.

The Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path is a model of yogic theory and practice. The Buddha was a consummate yogi, and while he may have refuted the mainstream metaphysics of Vedic-based yoga teachings, his own teachings and practice are firmly rooted in the broader yoga tradition, which predates both Buddhism and Hinduism. While the Buddha taught a variety of methods of practice, mindfulness is an essential aspect shared by them all.

The Sanskrit word smriti, most often translated in Buddhist contexts as “mindfulness” or “awareness,” literally means “what has been remembered.” To “re-member” is to “re-collect,” to bring back together all the seemingly disparate aspects of our experience into an integrated whole. In this way, remembering is synonymous with the definition of yoga itself. Whenever we see that our mind has wandered from the intimate, immediate, spontaneous, and obvious experience at hand, we remember to come back—to just this, right here and now, using the breath as the yoke.

In the Bhaddekaratta Sutta, the Buddha taught, “Looking deeply at life as it is in the very here and now, the practitioner dwells in stability and freedom,” a teaching that echoes Patanjali’s definition of asana as “stable and easeful.” In both the Anapanasati Sutta (Awareness of Breathing) and the Satipatthana Sutta (Foundations of Mindfulness), the Buddha tells us to observe the breath and then extend our awareness out to include the whole body. He says that the practitioner should be aware of the movements and positions of the body, “bending down, or standing, walking, sitting, or lying down.”

The applicability of this teaching to asana practice is obvious. When we combine awareness of breathing with asana practice, we can look to see how movement affects the breath, and how the breath moves the body. We can become aware of habitual patterns of reactivity. For instance, do you hold your breath when you reach out with your arms into a deep stretch? Do you unnecessarily tense muscles not involved with the movement you are making? Do you compare one side of the body with the other when doing asymmetrical postures? When you repeat a movement, do you find your mind wandering in boredom? As you maintain a posture, can you observe the constantly changing phenomena, or do you solidify the experience, conceptualizing and then relating to the phenomena as a “thing,” and either resist or grasp at it, depending on whether you find it pleasant or unpleasant?

Continuing to look deeply, we can begin to see our conditioned aversion to and grasping at different aspects of our experience. The four foundations of mindfulness taught by the Buddha include body, feelings (sensations), mental formations (mind), and phenomena that arise as objects of mind. When practicing asana, we can devote our practice to any one of these, or work through them sequentially.

In the following short sequence, I have chosen several asanas that provide an example of how we can approach the practice of asana as a vehicle of mindfulness and insight. They also function as postures and stretches that can strengthen our capacity for sitting meditation. As you move through them, please go slowly; explore with an investigative, nonjudgmental mind, just as you would in sitting practice. Honor your body’s present limitations, while letting go of any mental reactivity that may arise.

Corpse Pose

Lie on your back with your feet between twelve and eighteen inches apart, arms at your sides a few inches away from the torso with the palms up. Surrender the full weight of the body to gravity. Let the earth fully support the body. This is one of the four major meditation postures taught by the Buddha.

Spend some time resting your awareness on your breath, wherever it is that you feel it in the body. Letting go of any tendency to manipulate it, simply know an in-breath as an in-breath, an out-breath as an out-breath. Working with the first foundation, open to the breath and its various qualities: deep or shallow, fast or slow, rough or smooth, even or uneven. Scan the body. Is it fully released or still holding tension? When the mind wanders, gently, free of irritation and judgment, bring it back to the breath and the body.

Reclining Pigeon

From Corpse, bring both feet in near the buttocks, hip-width apart. Cross your right leg over your left, placing the outer right shin (just above the ankle) onto your left thigh. Then, bringing your left knee into your chest, reach between your legs with your right arm and around the outside of your left leg with your left arm and clasp your hands either just below your left knee or behind the knee on the back of your left thigh. Notice if you held or restricted your breath as you moved into this stretch, and continue to let the breath flow naturally.

Depending on the degree of openness in your hips, you may feel stretching sensations in your right hip. You may also sense some resistance to the sensations manifesting as tensing of the surrounding muscles. See if you can release this tension, and observe how the sensations change as you maintain the stretch. Begin to establish mindfulness of the body (the breath, the body’s movements and position), feelings (sensations that you may be experiencing as pleasant or unpleasant), mental formations (the resistance and aversion behind the muscle tensing), and objects of mind. Keep in mind that all phenomena are objects of mind: this means that we can focus our mindfulness not just on the body, sensations, and mental formations, but also on the impermanent, nonself nature of these sensations and mental formations; this focus will lead to—perhaps—the cessation of the clinging identification with the experience, the letting go of aversion, and a state of equanimity.

When you do the stretch to the other side, be aware of any subtle, or not so subtle, comparing and judging in the mind. Since we are not perfectly symmetrical beings, you may find that one hip provokes stronger sensations and reactivity than the other. One of my students once remarked that her left side was “the evil twin” of the right. It is just this setting apart in the mind that we try to avoid. Can we stay with the bare sensation, maybe even see the difference from one side to the other, without getting caught in judging or picking and choosing?

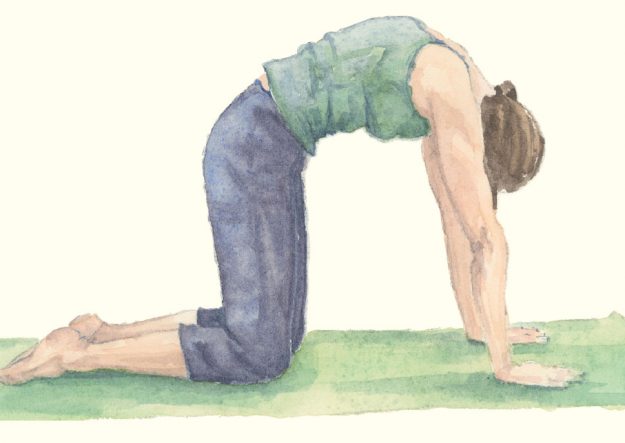

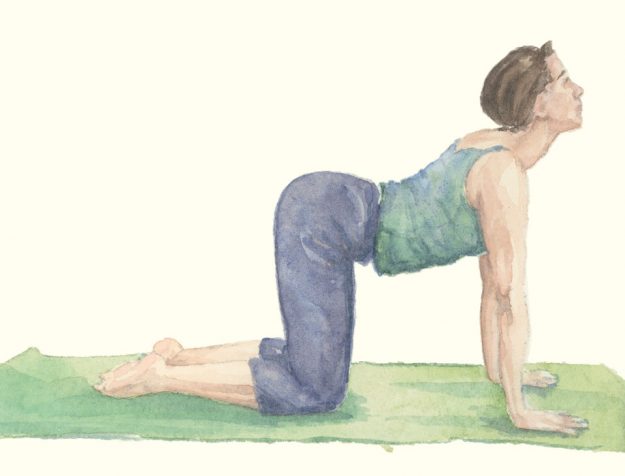

Cat/Cow

Coming onto your hands and feet, position your hands straight under your shoulders and your knees under your hips. As you exhale, round your back, pressing your spine up toward the ceiling, tilting the pelvis backward, scooping the tailbone between your legs. Let the head tilt forward so you are gazing back toward your thighs. On the inhalation, tilt the pelvis forward, opening your belly toward the floor and letting your spine move into the torso, creating a gentle backbend. Both the crown of your head and your tailbone reach up toward the ceiling. Be careful not to reach upward with your chin, which compresses the back of the neck.

As you continue to coordinate the movement with your breath, let the duration of the breath determine your pace. Notice how once you have gone back and forth several times, the natural tendency of the mind is to wander. This is our common reaction to repetition. It is as if our mind assumes that having done it already, it knows all about it and needn’t pay attention. This “knowing mind” is often the biggest obstacle to intimacy, whether with the experiences of our life or with others. Thinking we know, we stop listening and seeing. Keep the “don’t know mind,” and grow in understanding and intimacy. Keep remembering to come back to the breath, the very thread that keeps body and mind connected.

As you continue to coordinate the movement with your breath, let the duration of the breath determine your pace. Notice how once you have gone back and forth several times, the natural tendency of the mind is to wander. This is our common reaction to repetition. It is as if our mind assumes that having done it already, it knows all about it and needn’t pay attention. This “knowing mind” is often the biggest obstacle to intimacy, whether with the experiences of our life or with others. Thinking we know, we stop listening and seeing. Keep the “don’t know mind,” and grow in understanding and intimacy. Keep remembering to come back to the breath, the very thread that keeps body and mind connected.

From Cat/Cow, tuck your toes under and, reaching up and back with your sitting bones, straighten your legs into Downward Facing Dog. You may wish to keep your knees slightly bent at first and emphasize extending your back. Playfully explore the pose, stretching out the right calf by reaching the right heel to the floor, feeling the sensations as you linger here, breathing, and then alternate and stretch out the left leg. If you decide to alternate back and forth, coordinate with the breath and note the tendency of the mind to wander in the face of repetition.

Once you choose to straighten both legs, stay in the posture for anywhere from eight to fifteen breaths, staying alert to sensations, any mental formations that arise, as well as how the experience continuously changes. We tend to speak about “holding” the postures, but notice how there actually is no fixed thing to hold onto. Moment by moment, breath by breath, the posture is continuously re-created. The Dog of the first breath is not the same as the Dog of the sixth breath.

With practice, we begin to see that this is true not only for this asana, and all the other asanas, but also for all our experiences. We come to see that we are not the same “person” when we come out of the posture that we were when we went into it.

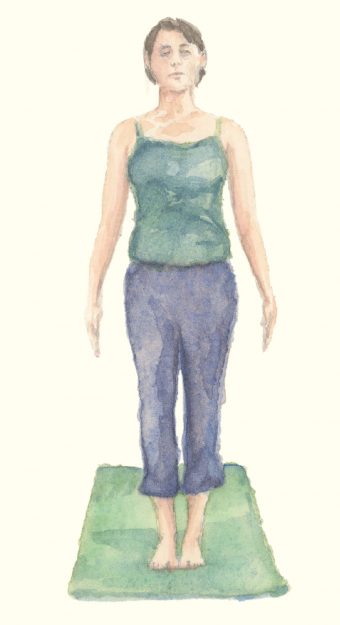

Mountain

Another of the meditation postures singled out by the Buddha, Mountain is too often perceived as just something we do between the more important asanas, while in fact it is foundational for all the standing postures. Pressing the four corners of your feet (the ball of your big toe, the point directly below your inner ankle, the ball of your little toe, and the point directly below your outer ankle) into the ground, distribute the weight of your body evenly between both feet and centered just in front of your heels. Imagine the pelvis as a bowl with its rim level front to back and side to side. Let the spine rise up, keep the lower ribs from jutting out, gently lift the chest, and open the heart. Relax the shoulders, with your shoulder blades moving into and supporting your upper back. Keep the chin parallel with the floor, not tilted up or down, but gently drawn in so that your ears are centered over your shoulders.

Another of the meditation postures singled out by the Buddha, Mountain is too often perceived as just something we do between the more important asanas, while in fact it is foundational for all the standing postures. Pressing the four corners of your feet (the ball of your big toe, the point directly below your inner ankle, the ball of your little toe, and the point directly below your outer ankle) into the ground, distribute the weight of your body evenly between both feet and centered just in front of your heels. Imagine the pelvis as a bowl with its rim level front to back and side to side. Let the spine rise up, keep the lower ribs from jutting out, gently lift the chest, and open the heart. Relax the shoulders, with your shoulder blades moving into and supporting your upper back. Keep the chin parallel with the floor, not tilted up or down, but gently drawn in so that your ears are centered over your shoulders.

See what happens as you simply stand there. Be awake to all the sensations that arise, the subtle swaying of the body, the movement of the breath. Is there boredom, impatience, or anticipation arising? Can you just be here? When you feel you’ve been here long enough, take another six to eight breaths and see what happens.

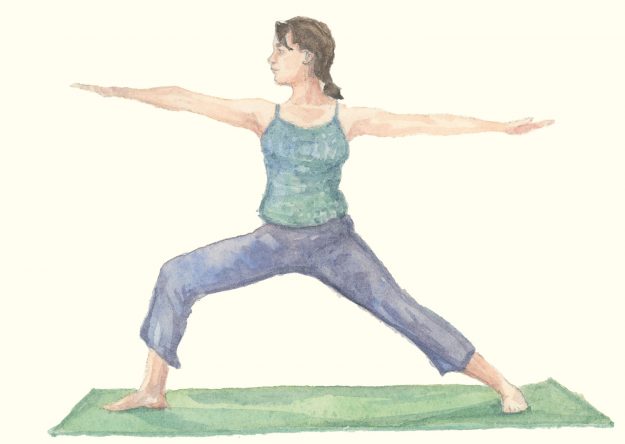

Warrior Two

Reach out to the sides with your arms parallel to the floor and step your feet apart so that they are directly under your fingertips. Turn your left foot in about 15 degrees and your right foot out 90 degrees. Without leaning forward, just bend the right knee toward a 90-degree angle so that the knee is directly over the ankle. Keeping your arms parallel to the ground, gaze out over your right hand.

As you breathe here, stay alert to changes in the quality of the breath, its depth and rate. As sensations begin to arise in your front thigh or in your shoulders, notice how the mind reacts with aversion, creating a “psychic amputation” as you tense around the sensations. See what happens to the quality of your experience if you stay with the breath while releasing this aversive tension. Notice the story lines that arise about what is happening and choose to just listen without grasping at any of them. Rather than solidifying the sensations into entities with which to do battle, embrace them with awareness. Notice, if you can, their conditioned, nonpersonal nature. With the letting go of aversion, and the self-identification, is there a qualitative difference in the experience? As one student put it, “There is a difference between discomfort and suffering.” The letting go of the mental anguish that we add to an experience is what the Buddha referred to as ceto-vimutti, “release of the mind,” a term often used in the Pali canon to signify enlightenment.

After doing both sides, come back to Mountain and just scan through the body, open to all that arises.

Seated Forward Bend

Sitting with your legs straight out in front of you, press the back of your thighs, calves, and heels evenly into the ground while

reaching through your heels and flexing your toes toward your head. Press your hands into the ground beside your hips as you lift the chest. Think of this as Mountain with a 90-degree bend in it. If your lower back rounds and your weight is coming onto your tailbone, sit up on a blanket or two so that you can get onto your sitting bones and allow the back to maintain its natural curvature. Grasp your feet or your shins, soften your groin and slightly rotate your thighs inwardly. Rather than trying to pull your torso onto your legs, lift your torso out over your legs, keeping the lower back from rounding. Those with tight hamstrings will feel this without having to bend very much forward. Let go of “grasping mind,” and be where you are. Eventually, those who are more flexible will draw the chest out onto the thighs, and the chin will come to rest on the shins.

Seated forward bends help cultivate a turning within and often come toward the end of an asana session. Feel the breath move within the body. Let go of any physical or mental tension. Surrender into the posture, and keep letting go of any clinging or aversion to the ever-changing phenomena. Notice how the attempt to prolong or create pleasant feelings is itself a form of tension, as is the act of resisting and pushing. Cultivate equanimity and compassion by staying open to all that arises.

When you are ready to come out of the pose, rest on your back, holding both knees into the chest. You may wish to take a gentle reclined spinal twist by letting the knees drop first toward one side of the body for a minute or so, and then toward the other side. When ready, rest in Corpse for a few minutes, letting the experience of the practice penetrate the body-mind. While asana practiced this way is indeed a form of meditation in action, sitting after asana practice is often a much more nourishing and satisfying endeavor. Why not try it now?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.