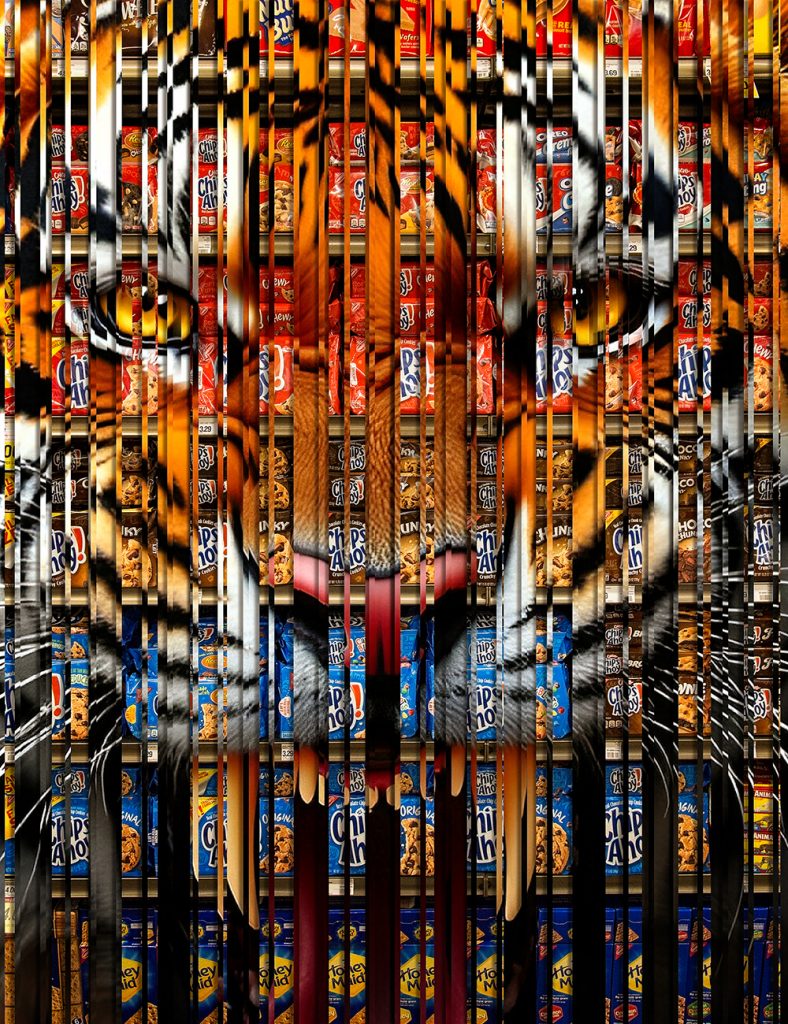

In my early 20s, I once stood for fifteen or more minutes in a supermarket aisle, frozen: I couldn’t settle on which cookies to buy. On many mornings I would stay in bed up to an hour, trying to figure out whether I should shower first and then have coffee or the other way around. These decisions may sound trivial, but that’s not how they felt in my body. My stomach knotted up, my chest tightened, and my mind got stuck in a loop, simultaneously racing and blocked—as if I were walking in the forest and I came across a tiger.

Choosing a package of cookies felt like facing an existential fork where my future split in two: the life I would have if I bought these cookies versus the life I would have if I got the other ones. And when something is going to determine your whole life, you need to avoid making a big mistake. Without any real data, though, I kept swimming in imagined possibilities of how the cookies would make me feel at breakfast, the kind of day I would then have, or the kind of person I would be. Rationally, I understood it didn’t make a difference, just as I knew it didn’t matter if I had coffee and then showered or showered and then had coffee; but I still needed to decide how to start my day, and I couldn’t figure out which was the right order.

Those things aside, I was doing very well. At only 21 years old, I was already making a living by touring and performing, winning an award for my first album. And then, my brain began to say I didn’t want to be a musician, that I didn’t actually enjoy it. I could not make sense of those baffling messages, which were so contrary to my values and desires, but neither was I able to dismiss them: They were there and felt real. The emotional charge they came with made me give them credence, and their content too was irresistible. How could you think such counterintuitive things in the first place unless they were true—unless they were powerful insights bursting through the membranes of your self-deception, from the depths of your core being?

As Kierkegaard wrote in his journal, life is understood backward, although we must live it forward. More than a decade after the cookie dilemma, as I began my dharma teaching career with a PhD in Buddhist studies under one arm and many hours of meditation under the other, I entered what was possibly the hardest period of my life to that point. Yet this time, in the tides of seeming progress and then regress, it became clear to me this was no mere rough patch. The answer came, both with pain and with relief, as a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Misunderstood among mental health professionals and highly misrepresented in the media, OCD has nothing to do with liking order or being particular about doing things a certain way. No one enjoys their OCD. If they need to organize their clothes by color, it’s more likely because they feel that otherwise something terrible will happen to them or to their loved ones. Common expressions such as “I’m so OCD about . . .” and “Everyone’s a little bit OCD” downplay this very debilitating condition. Yes: Many features of OCD are shared, at lower intensities, as part of being human. Who hasn’t obsessed about a strange occurrence or remote possibility at some point? But we don’t say “Everyone’s a bit clinically depressed” just because they feel sad or unmotivated on occasion. If you’ve ever experienced rougher-than-usual turbulence, of the “Cabin crew, take your seats” kind, you know how the body freaks out even though you know that all is fine. But beyond a certain intensity, you start to doubt whether nothing’s truly dangerous. This is how an OCD spike feels—but it can last for the whole flight.

I have spent a good deal of my life either managing or escaping from a sensation that something was off, when nothing was off except for that very sensation. With OCD, the amygdala sends alarm bells when, in fact, there is no danger in sight. So even though the survival response of freaking out is the natural thing to do, it is also the wrong one, for the threat was never real. Our brains get stuck on “wrongness.” Mistaking this for the underlying dissatisfaction that dharma teachings target, which can also manifest as an “off” feeling, can prevent those with OCD from finding the help they need alongside dharma practice.

I

got into Buddhism very early, taking refuge with a Tibetan lama at age 14. After leaving it in the background for a few years, I regained interest in the dharma around the time when—I now understand—OCD showed up in my life. Unconsciously, I gravitated toward a style of practice appropriate for this disorder. Sayadaw U Tejaniya, who became my main meditation teacher, would often say: “Don’t focus on the storyline, just recognize thinking is happening. Your experience is not your responsibility, your responsibility is just to be aware of it with right view.” Our responsibility, in other words, is to see experience as a natural phenomenon one need not identify with.

This, essentially, is treatment for OCD, a condition best addressed not with traditional talk therapy, which can be counterproductive, but with third-wave cognitive behavioral therapies. These have much in common with the dharma due to their influences from Buddhism and mindfulness. But this does not mean Buddhist practice will be enough to treat OCD. Being diagnosed and finding a specialist therapist made a big difference for me—a few things that had remained stuck, untouched by my practice, suddenly unlocked. I encourage any practitioner with OCD to seek the complement of specialized therapy. The two approaches work together so extremely well that I no longer differentiate between them, and a sizable chunk of my dharma practice—unconsciously in the past, consciously in more recent times—has consisted in dealing with my OCD simply because it’s part of how my mind works.

When we get trapped in the story of a thought, we go down the rabbit hole of figuring it out, arguing with it, neutralizing it, wondering what thinking this or that says about us. Most people have intrusive thoughts like “What if I open the car door in the middle of this roundabout?” or “What if I yelled out in the middle of a funeral?” or “Do I really love my partner?” Usually we brush those off as nonsense. Instead, someone with OCD may believe this means they’re dangerous to others or themselves and start acting on their compulsions to ease the anxiety. They may repeatedly confess their thoughts, ask others if they think they’re evil, pray compulsively, avoid the kitchen, review past experiences, count up to a lucky number, or ruminate at length about that thought. Seeing someone attractive can lead to googling “How do I know if I really love my partner?” and to hours spent online seeking reassurance that they didn’t cheat or aren’t in the wrong relationship. Driving to work, they may go back several times to make sure they didn’t run anyone over on the way. An innocent doorknob can become a mortal disease carrier that calls for endless handwashing.

OCD, sometimes called the doubting disease, is a checking disease too. What if, what if? “Well, let me check once more, just in case.” It’s a content creator trying to get into our fear-based algorithms—those that evolved to deal with actual tigers. It will exaggerate, distort, and use all sorts of tricks to make you watch its content. But every time you take the clickbait, you feed and strengthen the algorithm. It doesn’t matter if you like or dislike, share or hide the content. Trying to suppress or disprove a thought is still a form of “clicking” that keeps the wheel of OCD samsara going.

Dealing with the content of obsessive thoughts in any way misses the point, because your mind will sew a new costume for them—obsessions can shift to a different theme. To make the matter worse, most revolve around things with no definite answer, like what the right order is between showering and drinking coffee. As in the Buddhist parable of the poisoned arrow, I lie bleeding on the floor, demanding answers to impossible questions before I let the surgeon pluck the arrow out. Some experts say it’s about a need for certainty, like “Am I sure I won’t die from touching this doorknob?”; for others it’s about attributing relevance to thoughts that don’t deserve it, or confusing what is theoretically possible with a real probability. Either way, as long as I’m lost in the story of those questions, I don’t even see the arrow lodged in my chest.

The key is this: As with blinking, breathing, and many other autonomic functions, thinking can be done on purpose or it can happen on its own. If I ask what your favorite films are, thinking about that will differ greatly from other ideas that may pop up, off topic, as you’re making that list. Few things are more crucial for both OCD recovery and general dharma practice than getting clear on this distinction. We must recognize how a thought or feeling that visits us uninvited isn’t our responsibility—we should not judge ourselves for it. We didn’t do it, it’s something that happened to us. “It’s not me, it’s my OCD,” as the mantra goes. (Or to adapt it for a general audience: “It’s not me, it’s greed,” or fear, or aversion, or selfishness.) In contrast, clicking on that thought and running with it is an entirely different thing. As automatic as it feels, rumination is intentional. It takes some effort on our part, we’re doing it. And therefore it is optional.

As they say in OCD circles, thinking the same thought over and over doesn’t make it truer: It just makes it more stuck.

The Buddha admitted to having intrusive thoughts in his meditative journey, but he didn’t wonder whether they were true or what they said about who he was. Instead, he recognized what kinds of thoughts they were and, if they were not helpful and aligned to where he aimed to go, he did not engage with them. He avoided the second, intentional step of entertaining the thought. For “whatever one frequently thinks about and reflects,” he says, “becomes the inclination of one’s mind” (MN 19). The more we repeat the same thought pattern, the more justified we feel in giving it attention. Yet, as they say in OCD circles, thinking the same thought over and over doesn’t make it truer: It just makes it more stuck. A thought’s persistence need not signal a hidden truth or deep meaning but only that you’ve been thinking it for so long it has become a frequent, autonomous visitor. Its persistence feels increasingly convincing and generates emotions so loud it’s nearly impossible to not fall for the story. But the more you do, the more ingrained the pattern becomes, and the automatic thought blends with the intentional running with it into an indistinguishable blob of doubt, anxiety, and confusion.

The traditional antidote to doubt, the last of the five hindrances, is investigation. I never understood why. Investigating is what I’m obsessively doing already, I told myself. It’s what’s driving doubt in the first place! The more I dig, the deeper the hole I’m in. A list of pros and cons rarely solves anything when your doubt is obsessional rather than reasonable, and the compulsion to ruminate easily masquerades as inquiry. More generally, as contemplative practices interacted with our navel-gazing culture, it created an impression that the dharma is about looking within and figuring ourselves out. But many are already prone to overthinking and emotional absorption. Awareness alone is not enough—another of my teacher’s slogans. Being aware is not synonymous with a sort of self-psychoanalysis.

INVESTIGATE THE DOUBT

So how, then, should we investigate? Our minds need to be trained out of the habit of investigating the story and instead investigating the process of doubting itself. It is only when we see a thought as just a thought, and don’t rush to assign it any meaning, that we begin to notice its dynamics. No longer fooled by its particular narrative, the repetitive nature of the thought becomes much clearer. It’s like realizing that several films are actually the same film: If you set aside details such as characters and location, the same basic plot remains. We can observe how giving energy to discursive thinking aimed at “solving” doubts and obsessions actually fuels them, as do checking behaviors. We can also discern how those compulsions ultimately bring not relief but more distress—they’re unpleasant. Seeing this time and again, we comprehend the appeal of those patterns, as well as their trap, and, one hopes, begin to envision an alternative.

The alternative, though, is not necessarily to tune into our feelings. In fact, another feature of our navel-gazing is focusing too much on how we feel. But as someone with OCD painfully knows, feeling something doesn’t make that something true. Believing otherwise begins a descent into compulsions that can ruin your life. “Trust your gut” is especially bad advice for someone who has OCD. Our guts tell us we ran someone over or cheated on our partner but forgot. My whole body, physical and emotional, screamed at me that I didn’t enjoy making music. So whether it sends us thoughts or feelings, we cannot blindly trust our minds. What are we to do, then?

We must make our choices based on values. This is what the teachings on karma are about—karma means action, not consequence or destiny. It refers to the choices that shape our life in the present, near and distant futures. We must practice not identifying with the thoughts and feelings that come uninvited, and instead take refuge in what we choose to do with them, following our values. If out of nowhere your mind shouts “Push that old lady!” and you choose not to, which part are you going to identify with? Which will you judge yourself by? Along the way toward no judgment and no identification, this is a step many of us skip.

You’re not the one who chose to be irritated at your uncle’s remark or enticed by the latest smartwatch. Nor did you choose to have the thought of dropping your baby or driving into oncoming traffic. All that is just the nature of the mind. You are the one who chooses to disregard those thoughts and feelings as weird or unhelpful occurrences, the one who keeps holding your baby and staying in your lane. The point is not to try to eliminate the thoughts and feelings—this is yet another compulsion that perpetuates the cycle. Even the Buddha kept being visited by Mara, the personification of reactivity, throughout his life. But no matter the disguise, the Buddha recognized it every time: “I see you, Mara.”

In the same way that you can acknowledge the unwanted thoughts and feelings as neither you nor yours, you can accept their disturbing presence, proving to yourself that you can be uncomfortable without being drawn into the game, thus weakening the cycle of obsession and compulsion. Otherwise, you could be the one who chooses—although it may not feel that way—to take intrusions seriously, to follow the irritation or desire, to think you must do this or that to prevent something horrible from happening, to ruminate until you figure it all out, to doubt everything to death.

In this uncertain world, without a manual, being baffled is a given. Our minds do truly bizarre things. No wonder we ask ourselves what certain thoughts and feelings mean, whether or not we live with OCD. But underneath very often lies self-doubt: a lack of confidence in our agency and our ability to cope with life’s events. For we never know what might come next. Yet the funny thing with OCD is that when something bad actually does happen, we don’t deal with it any differently from other people. OCD doesn’t flare up in the face of actual danger, when our senses confirm that something is wrong. Instead, it mistrusts being safe, making up threats, or exaggerating the seriousness of potential ones.

Faith is the other antidote to doubt. I trust that things will turn out well, and that if they don’t, I’ll manage. Not because I have direct evidence for it—I may or may not—but because I choose to believe so. I choose the attitudes and actions that accompany that act of faith instead of those that come along with fear, its opposite. Fear is negative faith. Often with the very same lack of evidence, it believes the worst will happen. But when I receive that ominous message, it’s on me whether I take it seriously or file it away as irrelevant. This is what I can do: choose trust. Even today this is not an easy practice, but I know all too well the cost of the alternative.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.