My ordination master, Songnian, was renowned for his calligraphy and considered a National Living Treasure in Singapore.

We Chinese say the way you write tells a lot about who you are. Of Songnian, the man who shaved my head, they used to say, “His writing is without fire.” As a young novice I wondered at the cool, flowing quality of his characters; Songnian relentlessly pelted me with fiery insults and rebukes. I had to assume that his art was a window into a facet of his personality that I never saw.

Songnian had come from an aristocratic Chinese family and had been forced to flee the mainland when the Communists seized power in 1949. He drifted to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Malaysia, eventually settling in Singapore.

When I came to live in his small Mahabodhi Monastery, I was 21 years old and he was in his mid-eighties, an old man beset by ailments. Only four nuns lived in at Mahabodhi, and they were quietly delighted, almost smirking, by my arrival. As the youngest and most recent arrival, I would be his attendant and bear the brunt of his foul temper.

Mahabodhi was furnished with art and antiques. Money was very tight, so I assumed Songnian had bartered for these valuable items with his calligraphy. His strange and lovely bonsais were everywhere. The monastery felt like a scholar’s abode, and nowhere was this feeling stronger than by the big wooden table in the living room where he practiced calligraphy.

One day Songnian caught me watching him draw.

“Do you want to learn this?” he asked. There was something slightly sinister in his tone. With such questions, he was always up to no good. But I did want to learn calligraphy, especially from such a revered master.

“Shifu, thank you!” I eagerly replied and bowed. Shifu, an honorific, means “father-teacher.” I always had to say “Shifu” first when I addressed him.

Songnian scowled and dismissed me with a wave of his hand. The next day I was surprised when he called me by name as I was slipping past the open door of his study. I stopped, and he peered at me, not saying a word. His bushy eyebrows curled downward on their ends, almost touching the corners of his eyes. He looked like a fierce old owl.

His tools had to be exactly placed. An inch too far from him and he shouted: “Do you want to tear my ligaments? You torture an old man!”

I deferentially entered, and he beckoned me to his side with an irritated, impatient crook of his finger.

“Make ink,” he said, and he poured a pool of water into the shallow bowl of a traditional Chinese inkstone, a smooth black disc about six inches in diameter.

I took up the inkstick. Sticks are made from compressed charcoal and are ground against the stone to mix with the water and form ink. Their worth is judged by the charcoal’s density and the fineness of its grain. Burnt oils, medicinal herbs, precious metals, and glue can be added to the mix, creating subtle shades and aromas that you can detect in the calligraphy for decades.

Songnian put his hand over mine and began rubbing the stick’s nub around the bowl’s center in a steady circular motion. It was an intimate gesture, and I was slightly shocked.

After showing me the method, Songnian sent me away. You might imagine that making ink is quick and easy. It’s not. You have to endlessly rub around and around. Press too hard and your hands and arms get tired and you won’t be able to complete the task. Rub too gently and the ink does not come out.

Finally I had what I considered ink that was not too thick or thin. I knocked on my master’s door and set it before him.

“Numbskull!” he said. “Why are you rubbing it so wide? Do you think water is cheap? I have to pay the water bill.” My circular motion was apparently too far up the edges of the bowl, which caused the water to quickly evaporate. “Rub on one point.” He grabbed my hand and showed me what he wanted: round and round in tight circles in the center of the bowl.

“Let go,” he kept telling me as he guided my stiff and nervous hand. “Just follow it.” Our hands went round and round. Finally, I was able to feel his internal energy: his rhythm, movement, and degree of force. A transmission occurred. After that, making ink went smoothly.

When I started learning, I expected that I would soon be writing characters or at least practicing strokes in the preparation for writing characters. Yet weeks went by, and I was still making ink.

I grew increasingly bitter. Hadn’t the old man heard of prepared ink? Bottles of it were sold all over Singapore. He was living in another century. A dinosaur. My hands turned black. I rubbed and rubbed. Small tight circles. Fingers, wrists, and forearms ached.

If the ink was too thick, he scolded me. “Dimwit! Go away. Thin it out. But no more water!”

How do you thin ink without water? In later years, I realized you added thinner ink. As a young novice, though, I was completely baffled.

In addition to making ink, I had to master the exacting techniques for washing and drying Songnian’s brushes and cutting the rice paper on which he drew. This cutting was particularly harrowing. Each cut had to be absolutely straight with no ragged edges. I learned to crisply fold the paper and draw the knife across the inside seam. The motion had to be fluid and even, or the edge frayed.

“Where did you get that ape paper?” asked my master when my results were less than perfect. “You are still a monkey. Go and shave.”

The words “paper” (xuanzhi) and “monkey” (houzi) have a similar pronunciation in Chinese. He was telling me that the loose strands on the edges of the paper made it look hairy. Like an ape. It was an elegant put-down. He managed to be simultaneously clever, poetic, and insulting.

I learned to fold and roll the paper. If I put one wrinkle in the sheets, he screamed at me: “When the paper was with me, it was young! But with you, it’s grown old.” He spoke in metaphors and riddles.

His tools had to be exactly placed. An inch too far from him and he shouted: “Do you want to tear my ligaments? You torture an old man!”

If I put the paper too close, his words were a burning lash: “Seeds for hell! Why do you put it so near to me! Do you think I’m too old to stretch my arm?”

Often, after finishing work, he was as happy and contented as a child.

“Who drew this?” he asked, looking at me and smiling.

“Shifu!”

“Really? Was it me?”

“Shifu, I think so.”

“Wow! It looks so good. Did I do such a thing? How come I didn’t know?”

I was speechless.

Today, I realize this was a teaching. Songnian was pointing me toward something, although at the time I had no idea what it was.

A week after I left Mahabodhi to continue my Buddhist studies in Taiwan, Songnian died. I still had not drawn a single character. Before I left I was making ink, folding and cutting paper, and cleaning and drying brushes. My master must have sensed my frustration: his last instructions to me on the subject of calligraphy were “In writing the most important thing is not writing.”

It was over 15 years before I took up calligraphy again. The intervening period was filled with learning the meditation techniques of Chan and becoming versed in the Buddhist canon. I lived in Taiwan, Korea, Australia, and America. Finally, in my late thirties, I returned to Singapore to rebuild Songnian’s monastery and continue his work.

Today, I study calligraphy from a friend of my master’s, another old calligrapher who is harsh with his students—although now that I’m the abbot of a monastery he’s very nice to me! I’ve been working hard on my drawing, and I think I’ve made some progress.

I often think about those early days and the teachings of Songnian. I didn’t fully appreciate them at the time, but they’ve stayed with me. I have come to understand that through making ink, Songnian was teaching me in the traditional manner.

I still make ink by hand. The relaxed, firm, circular motion in the center of the bowl reconstitutes our fractured awareness to a single point. Too often, our minds are broken up, scattered about in bits and pieces. Our thoughts wander here and there. Just like my hand that once splashed the ink too high up the sides of the bowl, our minds are often sloppy and unfocused.

In contrast to my bitterness and frustration as a young man, when I make ink today I relish the single-pointed awareness that the process brings. Making ink insists on patience in a world where everything is quick and fast. We are accustomed to expect speed, ease, and comfort. Making ink is about making the effort, letting it come gradually, slowing down.

Making ink insists on patience in a world where everything is quick and fast.

I feel the paper the way my master did, gauging its texture and carefully dipping and shaping the bamboo brush’s tip. Calligraphy paper is delicate. Apply a brush that is too wet and the ink will soak through. Use too much force and the paper abrades or even tears.

Songnian dipped the brush in water, lightly dried it, and sculpted it by wiping it back and forth on a small square of paper he kept for this purpose off to one side. He brought the brush up to his eyes and took it in, connecting to its shape and texture. He dipped the bristles in the ink and swirled them around, assessing their effect on the ink. He stood in a martial stance, one foot forward, knees slightly bent—a stable, balanced posture, poised for forward motion. In fact, among his many accomplishments, Songnian was a martial arts expert. He was a tall man, broad across the shoulders and chest, strong even in old age.

Songnian always paused before he drew. This pause was powerful. He regulated his breath, and I could feel him empty himself. Then he drew in one fluid movement, smoothly moving forward and down over the white sheet.

As a young novice, I longed for such mastery and grace.

Today, when I make ink, cut paper, and wash and dry my brushes, I understand why Songnian insisted on precision in these seemingly mundane details. How are we going to accomplish big things when we can’t do small tasks? He was preparing me to shoulder the responsibility of the dharma and carry on his legacy.

Songnian didn’t just teach me to draw—he taught me the essence of drawing. The form is always available; it can always be copied. The essence is what needs to be taught, and this was what he transmitted. It was as small and precise as the tip of the brush; as simple and focused as the small circles of the inkstick in the bowl; as fluid and smooth as the cutting of paper; as vast as the universe, the source of creation that pours forth onto the white field of the paper.

Each time I draw I am grateful to be able to stand with one foot forward. I have inherited the bamboo forest, the pine for the charcoal, and the sun’s light and warmth that makes the forest grow. I dissolve into the ink, the white sheet of paper, the infinite universe that recreates itself moment by moment, always and forever changing and becoming.

“Who did this?”

I wonder.

Was it me?

Really?

Everything that comes into being depends on everything else. Nothing arises by itself.

In Buddhism, we often talk about “no self.” This is a difficult idea to grasp in English. What we mean is that the self as we usually imagine it doesn’t really exist. Just as the daffodil is made up of the nutrients it draws from the soil, the energy of sunlight, the water that helps it grow, and the bees that pollinate, so, too, we are made up of the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, the ancestors who have come before us and made our lives possible.

But does this mean that because the daffodil is composed of nondaffodil materials it isn’t a daffodil? Of course not! And likewise for each of us.

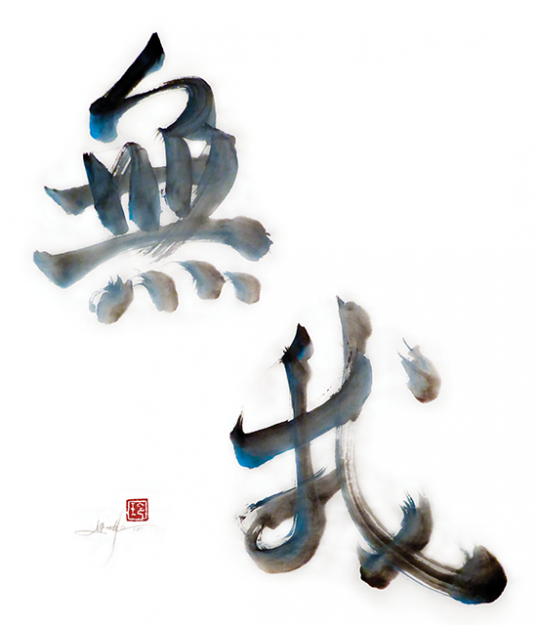

In Chinese the word for “no self” is wuwo, but wu does not mean “no” in Chinese. It negates rather than defines. It is indefinite. It is not fixed or concrete. Wu connotes fluidity, movement, even hope.

The realization of no self is not at all nihilistic. It simply means that the self is something different from what we habitually assume it to be.

In Chan, emptiness is not nothingness. And nothingness is not nothing. We might say “nonthingness” instead. No self might be better expressed as nonself. Not no, non-.

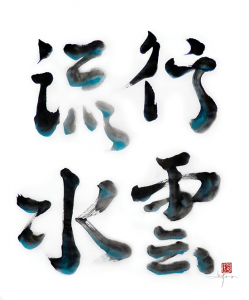

What is the meaning of nonself? Infinity. The downward sweep of Songnian’s hand came out of the place from which each breath comes and goes. Where each moment is born and vanishes. A place of nongrasping where there is complete freedom and everything comes together naturally. A lovely Chinese phrase, xing yun liu shui, expresses this. It means clouds flowing across the sky, a stream running downhill in spring without hindrance or obstruction, fully functioning, free but still connected, as clouds are connected to the sky and rivers to the earth.

When we realize that, we don’t feel terror or despair. On the contrary: to realize that, to live it, gives rise to a feeling of potential and possibility. We are no longer bound to the stifling attachment to who we think we are.

Everything changes, including each one of us. We get stuck because we limit ourselves. We do not really open up and become intimate with the world around us.

Where is beyond? Not no, non-.

When Songnian first taught me to grind, grind the inkstick, he was preparing me to hold a brush. You hold the stick to make ink in the same way you hold the brush to write. Both the shaft of the stick and the brush face downward at a right angle: only their tips touch paper or bowl.

Watching the way Songnian held the brush was mesmerizing. This grip is called xuquan, the hollow fist. His wrist was loose and drooped. Long fingers extended down the brush shaft. The graceful motion of his hand was so refined—the embodiment of Chinese art and culture!

I have learned to hold the brush as Songnian did, in the hollow fist. The hollow represents holding but not holding, what Chan calls effortless effort, the gateless gate. My grip is gentle but firm, as if I were securely cradling an egg.

Holding and gripping are different. Gripping is tense and forceful. Holding is flexible, fluid, and adaptable. The straight shaft of the brush can rotate a full 360 degrees. It is like the enso, the Zen circle without beginning or end. The gateless gate, through which we enter Chan, has no fixed point of entry. No fixed gate.

Songnian would begin his work from all points on the paper. He had mastered effortless effort. It flowed from the way he held the brush.

They say that when a tiger approaches, everything in the forest suddenly becomes completely still. There is a sense of presence, of imminence. And yet you may never see the tiger. As a young novice I could feel what I imagine is a similar atmosphere in the pause before Songnian drew: that same stillness, that same feeling of presence and power. In Chan, this is emptiness.

Songnian was always following me with his sharp eyes as I went about my tasks. I could walk in front of him once, and he would just stare at me. But if I walked twice, he would rebuke me: “Lazy cat!” (I was born in the year of the tiger.) “Why are you so idle? What a shiftless dolt you are! Go and scrub my bathroom floor.” He seemed to enjoy making me stop and attend to him when I was particularly busy. Sometimes I suspected that he would decide to do calligraphy when he knew I had a lot of work, out of spite. “Set up the table and put things in order,” he commanded. I had to drop whatever I was doing, make ink, and set out his paper and tools.

The laying out of his implements was an ongoing saga: there was no set way he wanted them placed. One day his brushes were on the left; the next, on the right. Sometimes they were below the paper; sometimes above. There was no fixed or definite pattern. It was the method of no method, effortless effort, the gateless gate.

Early on in my apprenticeship, I put the brushes in the position that they had been set out the last time he had drawn. I would invariably be scolded and told to rearrange them.

After several tongue-lashings, I thought I could outfox him. “Shifu, brushes left or right?” I asked the next time he told me to arrange the table.

“What do you think?” he replied. I was left to guess. And of course my arrangement displeased him.

“Stupid cat!” he said and left it at that.

The next time, I asked him again: on the left or right?

“Left,” he replied.

I couldn’t believe my good fortune. I placed the tools on the left.

Again I was scolded. “Wrong side,” he hissed. “Your left side is not my left side!”

The next time I asked, “Shifu! Your left or my left?”

“Which ‘left’ do you think?” he said, peering at me. I could only guess, and, of course, I was scolded.

The next day, I asked him again. This time he didn’t say anything—he just peered at me.

When I asked yet again, he said “No left!” Then he ignored me.

It was a maddening game. The deck was stacked: I could never win.

I actually use this same approach today with my students to point to the relative nature of appearances. My left is not your left. If I tell you to point to the left side of the room, will you point to your left or my left? Where is left? Your left is my right and so forth. Reality based on the perspective of subject and object is always relative. Songnian conveyed that fundamental Buddhist teaching to me in his own way.

It takes time to learn how to create the hollow fist. The hollow must be gentle; you cannot force it.

Gentleness gives space to others because it doesn’t impose and push its way. It allows you to be you and me to be me. Without sufficient space, there is friction.

Holding and gripping are very different. Try to find the gate and it’s gone. It’s everywhere and nowhere. Any point is the entry point.

When I miss Songnian, I prepare the table. I lay out my brushes. I make ink. I slow down. I hold the brush in the hollow fist. I don’t grip or grasp. I cradle the egg. I stand with one foot forward. I pause. Take a long deep breath. And then I draw.

♦

From Chan Heart, Chan Mind: A Meditation on Serenity and Growth, by Master Guojun. Reprinted with permission of Wisdom Publications. www.wisdompubs.org.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.