After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Roosevelt issued an executive order that began the largest forced migration in American history. During this period, over a hundred thousand Japanese American families were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to internment camps across the western United States. While this history of wartime internments based on race is well known, far less discussed is the role that religious affiliation played in the immediate days after Pearl Harbor, when many Buddhists were deemed a national security threat by the FBI and sent to high-security camps—a year before non-Buddhist Japanese Americans were arrested and sent to the camps en masse.

Given recent calls for a Muslim registry, this chapter of American history has now become especially relevant. Enter Duncan Ryuken Williams, a Soto Zen priest and Director of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture at the University of Southern California. Williams has spent the past ten years researching the history of Japanese American internment and the ways in which Asian American communities maintained their religious traditions throughout a time of extreme racial and religious discrimination. His soon-to-be-published book, “Camp Dharma: Buddhism and the Japanese American Incarceration During World War Two,” tells stories drawn from the letters, diaries, and memories of people who were torn from their homes and forced to live in squalid camp conditions.

One such family was that of 10-year-old Masumi Kimura, whose father, a first-generation immigrant, was a leader at a Buddhist temple in California’s Central Valley. After the FBI came to the family’s farmhouse one afternoon and wrestled Masumi’s father to the ground—unluckily, he had been holding a gun, preparing to chase rabbits from the vegetable garden—the elder Kimura burned every item in his home that contained Japanese text or had a “Made in Japan” label. Unable to bring himself to burn the family’s bound edition of the Buddhist scriptures, however, he swaddled the sacred texts in kimono cloth and rice cracker boxes and buried them in a hole behind the family garage.

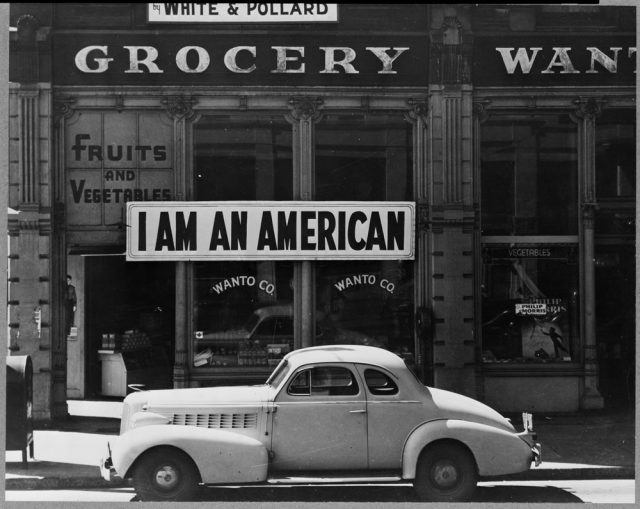

This narrative—moving in its own right—is a metaphor for the often unrecognized ways that Asian American Buddhist communities have shaped Buddhism in the West. On the surface it might appear that by burying their heirlooms to prove that they were assimilated Americans the Kimuras were erasing part of their Japanese and Buddhist identity; but in fact, their response had the effect of protecting their faith and heritage. The metaphor extends to the buried contributions of Asian Americans that have often gone unseen by convert Buddhists. The creative efforts of Asian Americans have preserved Buddhist teachings that today benefit all who practice in the United States.

At the same time, the story serves to illustrate how, in a country that prides itself on religious freedom, suspicion and bigotry can undermine even our most cherished values. Williams’s book, nearing completion, has taken on new urgency as the threat of religious and ethnic persecution by the government has become daily reality for millions across the United States and indeed the world. In order to shed greater light on the politics of the present, he generously agreed to share his knowledge of the past.

–Marie Scarles, Associate Editor

How did this project come about, and what drew you to the subject? I first became aware of the issue of Japanese American Buddhism and the World War II incarceration experience around 1999, when I was just about to finish up my graduate studies at Harvard University. My advisor, Professor Masatoshi Nagatomi, passed away right around that time, and I was asked by his wife to help clean up and sort his papers. In those papers—amid dissertation chapter drafts and letters from journals—was a handwritten Japanese document with the name Nagatomi written on it. The handwriting, however, looked different from my professor’s Japanese script that I was used to. I discovered that the document had been written by the Buddhist priest Shinjo Nagatomi, my professor’s father, as notes for sermons that he had delivered at the War Relocation Authority (WRA) Manzanar Buddhist Church during his incarceration there. I also found out that the senior Nagatomi was responsible for the calligraphy that adorns the ireito monument, which honors the deceased and still remains standing at the WRA Manzanar camp; it is featured in Ansel Adams’s iconic photo of that site.

Although my training in the study of Buddhism in Japan had not directly prepared me to understand the experiences of American Buddhists during World War II, over the next 18 years I collected other sermons, diaries, and letters written by Buddhist priests and laypeople and interviewed more than 90 people who had experienced life in the camps. The book is a result of the kindness of many individuals and families who shared their stories as well as institutions such as the Buddhist Churches of America, the University of Hawaii, Zen temples in Hawaii and on the U.S. mainland, and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, all of which opened their archives to me.

I was drawn to this story because it seemed like a critical part of understanding American Buddhist history, yet it had been overlooked by scholars of both Buddhist studies and Asian American studies.

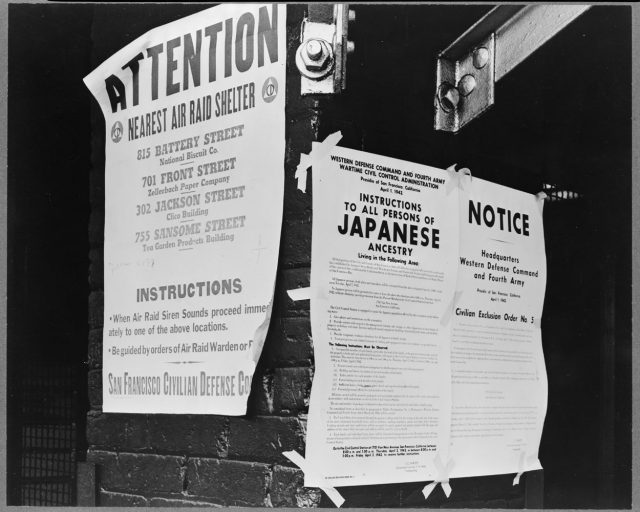

Did Buddhist identity play a role in how the U.S. government identified families and sent them to the camps? While the mass incarceration of roughly 110,000 Japanese Americans after President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 is well known, it is not so well known that the FBI separately arrested thousands of community leaders, including hundreds of Buddhist and Shinto priests (but almost no Christian ministers), in the days and weeks following the Pearl Harbor attack.

In this so-called selective internment program, one’s religious affiliation played a major role in determining whether one was taken away to a high-security Army or Department of Justice camp in any of a number of secret or remote locations. The FBI and military intelligence agencies had been conducting surveillance on Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines for several years prior to the outbreak of war and compiling lists (sometimes known collectively as the “ABC List”) of individuals whom the agencies deemed to be threats to national security. In fact, the first person to be arrested was the senior Buddhist priest of the Nishi Hongwanji tradition in Honolulu—at 3:00 p.m. on the day of the attack.

In the course of research for my book, I managed to declassify several thousand pages of confidential FBI, ONI (Office of Naval Intelligence), and Army G-2 documents detailing how intelligence agencies had conducted their own studies of potential threats to national security and contrasting Japanese American Buddhists and Christians; the latter were considered more “assimilated” and “Americanized,” while Buddhists were viewed as mysterious, dangerous, foreign “heathens.” So religion mattered a lot in the initial internments whereas race was emphasized in the decision for mass incarceration (which did not befall German and Italian Americans despite the fact that the United States was also at war with Germany and Italy).

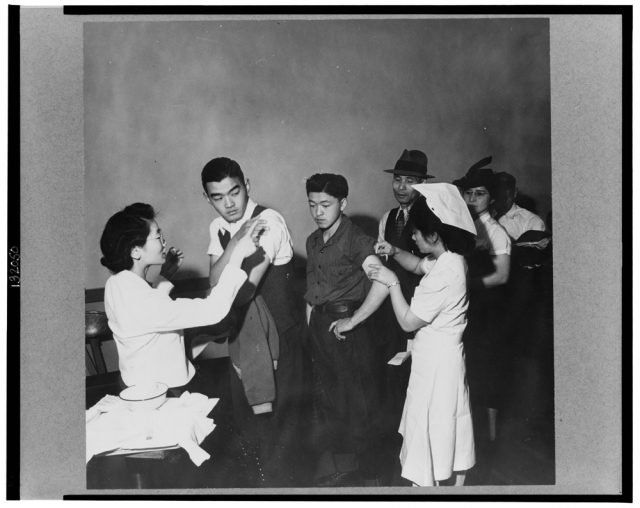

What were the families allowed to take with them? Those taken away in the initial internment to high security camps were often arrested suddenly and did not have the opportunity to pack even the essentials. Several Buddhist priests—the Pearl Harbor attack happened on a Sunday—were simply picked up at the temple and could not go home to retrieve clothes or toiletries. The head priest of the Jodo Buddhist tradition in Hawaii recalled that he spent the first several months in camp with only his Buddhist robes as clothing, even while being forced to perform hard labor (in violation of ethical principles like those stated in the Geneva Convention) in the construction of the camp at Sand Island, which would be his prison for the first several months after the outbreak of war.

Families who were forcibly removed from their West Coast homes, these families typically had between a week and ten days to report to an Army civil control station with only what they could carry. Imagine what you would take from your home to pack into a single suitcase if you were told by the government to sell your property and belongings within a few days. While many lost their businesses, homes, and furnishings, or could only sell them at far below their market value, many Japanese American Buddhists tried to carry at least some of their most valued possessions to camps, including Buddhist home altars or sutras. At many of the camps, the authorities banned anything written in Japanese in case it might contain subversive information, so books or Buddhist texts were often confiscated from people soon after their arrival in the makeshift camps called Assembly Centers.

“Imagine what you would take from your home to pack into a single suitcase if you were told by the government to sell your property and belongings within a few days.”

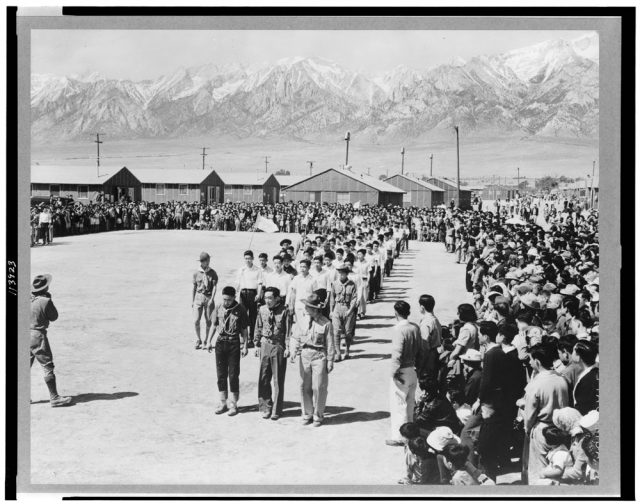

What were conditions in the camps like? The Assembly Centers were located in places like the Santa Anita Racetrack near Los Angeles or the Pacific Livestock and Exposition Center in Portland, Oregon, so the new “homes” for Japanese American families were in manure-covered horse stalls or pens for livestock that family members had to somehow make livable. Communal toilets without any privacy and Army-style rations eaten in mess halls suddenly became the norm for these families. The family of Tansai Terakawa, the head priest of the Portland Buddhist Temple, for example, managed to clean up their living space and even decorate it so that they could live in their new home with some dignity. In the photo I found of them, their space is adorned with an American flag and a photo of the Buddha, showing that they continued to keep faith in the promise of America as a land of religious freedom, and that they could maintain their identity as both American and Buddhist.

How was Buddhism practiced in the camps? In what ways was it stifled, and in what ways did it thrive or change? Once they were transferred in the summer of 1942 from the Assembly Centers to the more permanent WRA-run camps, Buddhists immediately went about the task of recreating the dharma behind the barbed wire fences. Although camp authorities tacitly encouraged Japanese Americans to affiliate themselves with Christian organizations, to speak English only, or to play American sports like baseball, officials also recognized that they couldn’t constitutionally prohibit the practice of Buddhism in the camps. Thus Buddhist temples were established in makeshift barracks, with temple altars constructed out of scrap wood that the internees scavenged and sculpted.

Buddhism in the WRA camps ended up thriving because the dharma offered a viewpoint about suffering, loss, and death; during the first winter a large number of babies and elderly people did not survive the intense daytime heat and severe nighttime cold in the camps’ poorly made barracks, which were often located in remote desert regions.

Also, the social aspect of belonging to a sangha—even one behind barbed wire—made the barrack temples a community center for both the young and the elderly.

In their attempts to “Americanize” Buddhism, though, the camps drove the process of chanting Buddhist “hymns” in English as well as organizational reforms to cut the ties of each Buddhist sectarian group with their headquarters in Japan. The largest Buddhist group, the Nishi Hongwanji organization, for example, changed its legal name from the Buddhist Mission of North America to the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA) in 1944 at the WRA Topaz camp to emphasize that its new home was rooted in America.

Another aspect of the “Americanization” of Buddhism was the effort made by members in the camps of the Young Buddhist Association (YBA) as well as sympathetic white Buddhist priests to “universalize” the religion by asserting that the dharma was a teaching that was applicable and open to people beyond the Japanese American community. Indeed, in the revival of Japanese American Buddhist temples on the West Coast and Hawaii after returning from the camps, leaders welcomed people beyond the community even as they helped the dislocated find shelter and jobs after the years of living behind barbed wire. The Rinzai Zen priest Nyogen Senzaki, for instance, who had spent his war years in the WRA Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming, taught new convert Zen Buddhists like Robert Aitken, who would later go on to found the Diamond Sangha in Honolulu. During this period also, the traditionally ethnic Jodo Shinshu BCA temple in Berkeley, California, was attended for a time by the future poet, environmentalist, and Buddhist priest Gary Snyder, then a relatively new student of Buddhism. Zen temples like Zenshuji in Los Angeles or Sokoji in San Francisco also opened their doors to people from all ethnic backgrounds who were interested in Buddhism. These historically Japanese American Zen temples, whose leaders included Taizan Maezumi and Shunryu Suzuki, respectively, were two important pillars in the postwar boom in American Zen Buddhism. Thus, one somewhat unintended consequence of the World War II incarceration experience was an accelerated broadening of the sangha and the spread of Japanese lineages of Buddhism into the mainstream American public.

What was the response of non–Japanese Americans to the internment of Japanese people in the country? The vast majority of white, black, and Latino American citizens strongly endorsed the mass incarceration of the Japanese American population. Even Asian Americans, particularly those of Chinese, Korean, and Filipino heritage (those whose ancestral homeland had been colonized by the Japanese imperial forces), found that though they shared with Japanese Americans the longer history of anti-Asian restrictions on immigration or “yellow peril” exclusions from naturalization or land owning, the conflation in American minds of the Japanese American community with the Japanese enemy meant that few Asian Americans stood up to assist this community. Even organizations with a history of supporting minority civil rights like the ACLU or national Jewish and black organizations did not vocally oppose the targeting of the Japanese American community.

A handful of liberal Christian organizations and former missionaries to Japan did voice their concerns and wrote letters, especially to Eleanor Roosevelt, who was known to be more sympathetic than her husband to the plight of Japanese Americans. Among the Buddhist community, several white Buddhist priests on the mainland like Sunya Pratt of Tacoma Buddhist Temple and Julius Goldwater of Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Temple were immensely helpful in organizing storage space in the temples for belongings that internees could not take to camp. They also traveled to a number of WRA camps in order to bring Buddhist ritual items to their fellow sangha members, even those imprisoned in camps as far away as Arkansas. In Hawaii, the Soto Zen priest Ernest Hunt was instrumental in keeping the temples on all the islands safe by coordinating with the military government that had imposed martial law on the islands and banned Buddhist and Shinto practice during the war (though they encouraged Japanese American Christian churches). For helping their fellow Buddhists, these liberal people were often derided as “Jap lovers” and taunted by their white neighbors.

Does the internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans parallel the discussion of a Muslim registry today? If we understand that the Japanese American mass incarceration during World War II was an incremental process that began with prewar surveillance of temples and Buddhist priests, as well as the making of “registries,” or lists of those priests who were considered to be national security threats, and ended with forcibly placement in detention camps behind barbed wire, it is reasonable to be concerned about the fate of Muslim Americans in the current political climate. All it takes is a president issuing an executive order (like EO 9066 in February 1942, which for legal purposes didn’t explicitly mention either race or religion) to create conditions for a “military necessity” for the roundup and incarceration of citizens.

The main way the situations differ, though, is that in 2017 many people of all faith, racial, and ethnic backgrounds have joined with groups like the ACLU and other organizations interested in preserving American democracy, civil liberties, and constitutional guarantees of religious freedom, so there is far more vigilance about undue attacks on Muslim American individuals, families, and refugees.

How have the years of research and writing challenged—or enriched—your own perspective on the development of Buddhism in North America? I began writing early drafts of chapters in the book in 2008, just when Barack Obama had won the election and had made the pronouncement “Whatever we once were, we are no longer just a Christian nation; we are also a Jewish nation, a Muslim nation, a Buddhist nation, and a Hindu nation, and a nation of nonbelievers.” This was one of the clearest endorsements to date by an American president of a pluralistic vision of the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of religious life in America.

In the intervening years, and especially during the Republican primary race and ultimate election of Donald Trump as the president of the United States, we often heard the rhetoric about “America as a Christian nation.” There was talk of allowing Syrian refugees into America, but only if they were Christian. The more recent executive order and travel ban’s exclusion of persons from certain Muslim-majority nations seem premised on the notion that non-Christians are more likely to pose a threat to national security.

Indeed, there is a long history in America of the idea of Anglo-Protestant normativity, or the notion that America is fundamentally a country that belongs to Anglo Protestants, with “Anglo” understood both in the racial sense of white and the linguistic sense of English-speaking. (We would do well to recall, by the way, that prior to the rise of prejudice against Muslims and Buddhists, there has also been anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic sentiment in American history.)

We therefore have pendulum swings between decades when the notion that America is a Christian nation comes to the fore and those when the idea that America is a free nation is emphasized. Both ideas have always coexisted here. American Buddhists have a role to play in determining how to create the conditions necessary for the greatest number of diverse populations to be able to freely practice their faith in America.

Can you comment on how a greater knowledge of the experience of ethnically Asian American Buddhists can further an understanding by Buddhists of all kinds of the religion’s development in the country? Learning about Asian American Buddhists is to learn about our neighbors, our classmates, and our colleagues. To understand the history of Asian American Buddhism is to come to know how Buddhists have made America their home for over a century and how our pioneer dharma ancestors made tremendous strides in carving out a place in the American religious landscape for Buddhists of all ethnic backgrounds. In 1927, Japanese American Buddhists from Hawaii earned a legal victory in the U.S. Supreme Court case Farrington v. Tokushige, which secured a judgment from the highest legal body allowing Buddhist temples on the Hawaiian islands to teach Japanese language and culture, something that the legislature and Christian missionaries vehemently opposed and passed laws against. During World War II, Japanese American Buddhist soldiers sacrificed their lives in the European theater in a segregated unit (the 442nd Regimental Combat Unit, the most decorated unit in U.S. Army history) and in the Pacific theater as linguists in the Military Intelligence Service (General MacArthur’s staff claimed that their service had shortened the war by two years). Their sacrifices secured the designation of “B” for “Buddhism” on U.S. military dog tags, Buddhist chaplains in the armed services, and the placement of dharma wheels on tombstones at national cemeteries. Today, two Asian American Buddhists (Senator Mazie Hirono and Representative Colleen Hanabusa, both D-Hawaii) and one African American Buddhist (Representative Hank Johnson, D-Georgia) have broken the barriers of representation in Congress. To understand how it is possible and much easier for Buddhists today to claim both their Buddhist and American identities, it is critical that we have some understanding of the hardships and sacrifices of our Asian American dharma ancestors.

Understanding this history also allows those of us who live in contemporary times to appreciate how Buddhism is a multifaceted religious tradition that supports the development of wisdom in the most difficult of circumstances, whether those karmic situations are personal, familial, societal, or related to a political or even global geopolitical reality that seems to be intractable. Looking back on the Japanese American World War II experience can also draw out what it means to truly have compassion for all beings, regardless of one’s race or national origin; or how to develop a spiritual practice that understands how our conditional present is causally linked to conditions in the past, and to know how particular sangha communities are interconnected with a diversity of communities. We are not alone.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.