In February 2001, Mullah Omer, leader of the Taliban, issued his infamous decree: all pre-Islamic art in Afghanistan was to be destroyed, including the two great Buddhas carved into the sandstone cliffs of Bamiyan. When Rob Schultheis began this article—a history of the ancient monument and the people who built it—the Buddhas were still standing.

The first historical account of the Buddhas of Bamiyan—the larger of which is said to have been the tallest Buddha in the world—comes to us from 632 C.E., in the words of the great Chinese pilgrim Hsuan Tsang. Hsuan was in the midst of an epic ten-thousand-mile trek along the Silk Road, to the westernmost outposts of the Buddhist world. Much of what is now Afghanistan consisted of small Buddhist kingdoms then, but the countryside was wild and lawless. Hsuan writes of narrow, precipitous trails, of snowdrifts twenty to thirty feet deep, of demon-haunted passes and murderous bands of robbers.

When he finally crossed the last crest of the Koh-i-Baba Mountains and gazed down into the Valley of Bamiyan, he beheld a marvelous sight: “To the northeast of the royal city of Bamiyan stands a sheer mountainside . . . and in a niche in its walls stands an erect stone Buddha. Its golden hues sparkle on every side, and its precious ornaments dazzle the eye with their brightness.”

The Great Buddha was 180 feet high, carved out of the conglomerate sandstone of the cliff, with details of features and robes added in wood, stucco, and polished brass and gold. The image was clothed in a huge brilliant red cloak, representing the Supranatural Buddha, Lord of the Cosmos. The niche around it was decorated with delicate frescoes in every color of the rainbow. A few hundred yards away, in another cleft in the cliff, stood a second Buddha, 125 feet high, also decorated with shining metal. This lesser figure, clothed in blue, represented Shakyamuni, the historic Buddha. The cliffs around the statues were honeycombed with the caves and aeries of ten monasteries, housing over one thousand monks.

The Bamiyan brand of Buddhism regarded the Buddha as a timeless expression of the divine as well as a human being and teacher. This Buddhism was also the basis of the valley’s political life. Bamiyan was ruled by a royal family of Turkic princes who eventually became vassals of the T’ang dynasty. Every five years, the valley’s inhabitants gathered for a great festival, during which the rulers offered up their wealth and earthly power to the Buddhas and their monastic caretakers. The chief monks accepted the offering and then returned it to the royal family, certifying their status as temporal and worldly representatives of the dharma. Despite these theological idiosyncracies, Hsuan Tsang was greatly impressed by the religious devotion of the people of Bamiyan. “These people are remarkable among all their neighbors,” he writes, “for a heart of pure faith, from the Three Jewels, Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, to the one hundred benevolent spirits.”

In the ninth century, the Bamiyan Valley, along with the rest of Afghanistan, converted to Islam. The Western view of Islamicization is invariably violent: invasion, blood, forced conversion, and slaughter. That isn’t necessarily true. Islam may describe itself as the Religion of the Sword, but more often than not it has spread by the persuasion of its creed, especially along the Silk Road, where religions, silkworms, gunpowder, horses, and legends flowed with ease. Some Mongol tribes along the road converted from shamanism to Buddhism, to Nestorian Christianity, to Judaism, to Islam, and back again with barely a tremor.

Over the centuries, the Bamiyan Valley endured repeated invasions. In the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan sacked the city of Bamiyan and its hilltop fortress opposite the Buddhas; the ruined fort is known locally today as “the City of Screams,” because of the horrors he perpetrated there. Many of the Khan’s armies stayed on and settled in Bamiyan, intermarrying with the surviving locals. The Great Buddhas remained untouched.

By the nineteenth century, the descendants of the Buddha-builders and the later Mongol invaders had become a distinct tribe called the Hazaras. Their territory in Afghanistan’s central mountains, known as Hazarastan or the Hazarajat, remained on the fringes of Afghan society. The other Afghan tribes were ethnically Indo-European, and followers of Sunni Islam. Physically, the Hazaras resembled their Mongol and Sino-Tibetan ancestors; and, like many minority groups in the Muslim world, they were Shia Muslims. Shiism has always had a strong sense of political and social justice, of antiauthoritarian populism. Other Afghans, particularly the Pashtun tribes who ruled the country, persecuted the Hazaras out of both ethnic and religious bias. From 1880 through 1901, the Afghan king Abdurrahman systematically attempted to exterminate the Hazaras. Tens of thousands of Hazaras were massacred; tens of thousands more were sold as slaves or forced to flee as their lands were handed over to Pashtuns. “All those who have rebelled against me, the Amir of Islam, must be annihilated,” the king wrote to his fellow Pashtuns. “Their heads shall be mine; you may have their fortunes and children.” The first major damage to the Buddhas occurred under Abdurrahman: the faces of the two statues, offensive to the king because of their Mongol features, were hacked off, the legs and torsos damaged by artillery fire.

Hundreds of thousands of Hazaras emigrated in a massive diaspora, settling in Kabul, Herat, and other Afghan cities, and even farther from their homeland, in Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and India. (A whole community of Hazaras in India worked as coal miners; during the First World War the British recruited them as sappers, and many fought on the Western Front, tunneling under the German trenches and blasting them from below with explosives.)

Like Ararat to the Armenians and the Western Wall to the Jews, the Buddhas of Bamiyan became a symbol to exiled Hazaras of their lost homeland. When I first visited Afghanistan in 1972, I got to know several Hazaras living in Herat. They held the poorest jobs in Herati society: as sweepers and scrubbers in hotels, firewood-cutters, ditch-diggers, and haulers of brick and stone. In almost every Hazara house or room, you saw the same two cheap colored pictures hanging: one of the Blue Mosque in Mazar-i-Sharif, sacred to Ali, the founder of Shia Islam; and the largest of the two great Buddhas. “We have lost our homes,” they would say, “but we have them with us, wherever we wander in the world.”

I first saw the Buddhas of Bamiyan for myself in the winter of 1998. I had spent much of 1984 through 1993 in Afghanistan, covering the Soviet invasion as a journalist and working on and off for various human rights programs. Somehow, I had never made it into the isolated Bamiyan Valley; few reporters and aid workers did: it was just too rough, dangerous, and remote. Even for the people of Bamiyan, so accustomed to hardship, these were harsh times. Azra rozi az, az sang paida mona, as the grim Hazara proverb says. “A Hazara must find his bread in the stones.”

Now I was part of a small medical aid mission to Bamiyan whose aim was to deliver medicine and conduct a survey of famine conditions in Hazarastan. Once the Afghan resistance fighters, the mujahedin, had driven the Soviets from Afghanistan and overthrown the Marxist regime in Kabul, they had turned on each other, party against party, tribe against tribe. On one side were the more moderate Tajiks, Uzbeks, and other minority groups; on the other were the now-notorious Taliban—the Pashtuns, united under fundamentalist Sunni mullahs and backed by Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, the Gulf Emirates, and, many Afghans believed, the United States. The Hazaras, as usual, had been caught in the middle. Their great tribal chief, Mazari, had been captured by the Taliban under a flag of truce, tortured, and thrown out of a helicopter over Kabul. Around the same time, the anti-Taliban commander Achmadshah Massoud, a Tajik, had massacred some eight thousand Hazara civilians in west Kabul. Now, as Massoud and the Taliban fought on to control the country, the Hazara leadership had retreated to their beloved valley.

The doctors and I flew with a ton and a half of medicine from Los Angeles to Bangkok, and on to Uzbekistan. From there, an unmarked, battle-worn Antonov transport plane flew us and our cargo across the battle lines to a snow-packed airstrip on the high plateau above Bamiyan; the Bamiyan airport was closed due to Taliban bombing raids. From there Hazara guerrillas hauled us, along mountain roads lined with six-foot snowbanks, down to the valley. The State Department had given us dire warnings about our expedition. The Hazaras were fanatics, they said, led by Iranian advisors who hated Americans and who would either execute us or hold us for ransom. Instead, we were greeted in every desperately poor village along the way by cheering crowds, peasants holding up banners of welcome, and by schoolchildren singing in the thin cold air.

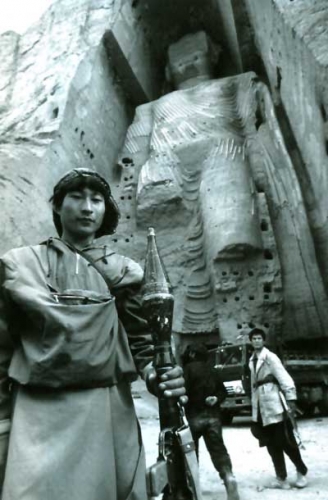

As evening fell, we entered Bamiyan Valley. Cut into the high cliffs, towering in the roan light, the two great Buddhas stood, gazing with eyeless faces. Their gold, paint, and ornaments were long gone, and they bore the ravages of time and abuse, but that only seemed to add luster to their ageless grandeur. Dust, stone, sunset, the inexorable shadows . . . At the feet of the Buddhas, in the sere and barren fields, skinny kids stood guard with AK-47s and RPG-7 grenade launchers, their faces muffled against the bitter cold. Shia guerrillas, guarding the ancient statues. The old monks’ caves were crowded with refugees from the Taliban, and the blue-gray smoke from their cooking fires spiraled into the dusk.

During our time in that snow-filled valley, I saw how alive those old bedrock images still were. Signs around the base of the cliff urged visitors: PLEASE RESPECT THE BUDDHAS. A group of elderly Hazaras insisted that we sign a heavy, hardbound register that recorded all who came there. In a small building nearby were stacks and stacks of these guest books, dating back decades: hippies from Holland; dopers from Leeds and Newcastle; Australian surfers on global walkabout from Bondi to Goa to Spain; Buddhist pilgrims from Japan, Thailand, Vietnam . . .

I remembered my old British friend Harry Luke, my best friend when I was studying under Geshe Ngawang Darjay in Dharmsala in ’72. Harry had been bumming his way east, with nothing very much on his mind, when, on his way to Kathmandu, fate had detoured him to Bamiyan. He’d spent weeks there, he told me, somehow unable to leave. Every evening he climbed the steep stairway to the Great Buddha’s head, where he sat, smoking hashish and tobacco in a clay bong he had bought from a Senegalese street vendor in Earl’s Court, looking out over the oasis, the dry hills beyond, and the snowy peaks of the Koh-i-Baba, the Father of Snows.

And then, one evening like all the rest, as he was crumbling up the sweet heavy resin in his hand, getting ready to light up, he dropped the bong. He grabbed for it, missed, and watched it tumble slowly away into the void, past the Buddha’s eyeless visage. He’d been reading a tattered paperback copy of the Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa in his cheap hotel in Bamiyan. As he watched his pipe vanish forever, he thought of Milarepa’s lines regarding the loss of one of his two possessions:

My old clay bowl was only an old clay bowl,

Until it shattered—

then it became a priceless lesson in Impermanence.

Harry never smoked again. The next day he left Bamiyan for Kabul, where he caught a bus over the Khyber Pass into Pakistan. Two weeks later he was studying the dharma with Thubten Yeshe at Kopan Gompa, near Boudnath Stupa in Kathmandu.

But not everything about those innocent, revelatory days was gone. When I met Khadeer Khalili, Mazari’s successor as chief of the Hazaras, he spoke with real warmth about the Buddhas. “When this war is over, the first thing we must do is repair the statues. They have suffered greatly over the years. We must never lose them.” This, during a winter when hundreds of Hazaras were starving to death under a Taliban economic blockade and refugees flocked constantly into the valley with horror stories of rape, murder, torture—the hellish business we call “ethnic cleansing.”

Khalili told me more stories. There was a mullah in a neighboring valley, he said, his eyes shining, who had recently been called to the scene when a farmer unearthed in his field another Buddha statue, small but exquisitely beautiful. The mullah was torn between excitement at the discovery and the memory of passages in the Holy Quran excoriating idolatry. Finally, the mullah got his rifle, shot the statue between the eyes, and then had it carefully transported to Bamiyan to be preserved!

“Our ancestors were great men,” Khalili told me. “They had many secrets.” With a conspiratorial air, he produced a small, carefully tied cloth packet. He opened it up. Inside were the pages of an incredibly ancient-looking Talmud that another farmer had recently unearthed in his fields in Bamiyan. Black letters on parchment the color of old bones. “There were Buddhists here; there were Jews here,” he smiled. “Now we are Shias, Believers, Followers of the Prophet, peace be upon him. But we are still proud of our ancestors.”

When we helicoptered out of Bamiyan at the end of our stay, I caught one last glimpse of the Buddhas tilting away below as we banked north toward the Amu Darya and Uzbekistan.

I came back one more time, two summers later, to report on the ongoing famine in Hazarastan. This time I flew in on a World Food Programme plane from Pakistan and landed in Bamiyan. Things were much worse now: the Taliban had captured Mazar-i-Sharif and massacred thousands of Hazara civilians, cutting their throats and burying them in mass graves. They had defaced the Mosque of Ali, and they were closing in on Bamiyan itself. The anti-Taliban Northern Alliance under Massoud was steadily losing ground, thanks to weapons and fuel and hordes of Arab and Pakistani mercenaries. More and more, the Hazaras were isolated in their mountain stronghold.

Still, the spirit of the Buddhas seemed undiminished. Hazara women held literacy classes for farmers’ wives and daughters in the caves by the Great Buddha’s shins. The old caretakers still recorded your name and asked, “What is your good country?” when you visited the statues. The kids with guns still guarded the sacred ground at the foot of the cliffs. I used to walk up there two or three times a week, sometimes with my friend the Professor, a scholarly, ascetic-looking middle-aged Hazara who worked for the U.N. and had an inexhaustible store of native legends and fairy tales—tales of wolf-women and snake-women, enchanted springs, and the hot pool known as the Tears of the Dragon. And there was the more recent story of Lum-Lum, the Lame Man, an elderly crippled Hazara who led the fight against the Soviets back in the 1980s. After the Soviets killed Lum-Lum, they tied his body to a tank and paraded around the valley with it. Hazara elders warned them that what they were doing would rebound upon them, but the logical Marxist-Leninist Soviets scoffed. That same day the tank bearing Lum-Lum’s body careened off the road and the entire tank crew was killed. Lum-Lum’s body was retrieved by local villagers and concealed in a cave nearby. When Lum-Lum’s family claimed it months later it was uncorrupted, undecayed, as if he were simply asleep.

When the Soviets left Bamiyan, Lum-Lum was buried at the foot of the Great Buddha, the most hallowed ground in Hazarastan. Cliff swallows dove and cried in the shadows around the Buddha’s head. The call to evening prayers soared over the rooftops of the town below.

I’d planned to return to Bamiyan in order to start a medical training program; I’d planned to train and equip “barefoot doctors” to work in the outlying villages where health care was virtually nonexistent. Several U.N. agencies were interested in helping with it, as were the Iranian medics working in the valley. But before I could begin, word came that the Taliban had captured Bamiyan, overwhelming its defenders with massive numbers of fighters equipped with tanks and artillery and backed by jets and helicopter gunships, the best that Arab oil money could buy.

According to a U.N. worker, the last Westerner to leave Bamiyan, the old men who kept the Buddhas’ visitors’ books took them out into a pasture and buried them as the Taliban forces closed in on the town from the south and east. “They will be there when Bamiyan is free again,” they told him. The next day the Taliban came, and the killing and raping, the burning and looting began.

At first, Mullah Omer, the Taliban leader and self-styled “Emir” of Afghanistan, insisted the Buddhas would not be harmed. But photos were somehow taken and smuggled out, showing that the body of the Great Buddha had been severely damaged, probably by artillery or tank shells.

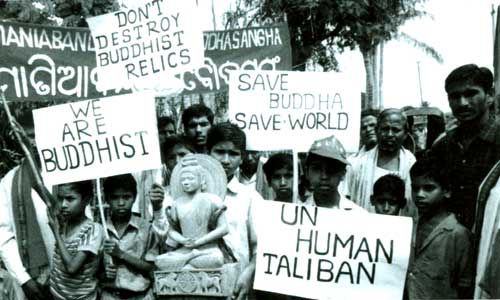

Over the next two years, those of us who know and love Bamiyan and the Hazara people held our collective breath. The valley was briefly liberated by the Hazara resistance under Khadeer Khalili, and then recaptured by the Taliban. And then, in February 2001, Mullah Omer issued his infamous decree: all pre-Islamic images in Afghanistan must be immediately destroyed, including the Buddhas of Bamiyan.

Some ill-informed sources in the West have described the Taliban’s idol-smashing as a homegrown phenomenon of “rural Afghan Islam”; in reality it is something much more sinister, part of a cult-like form of Islam, part Saudi Arabian, part Indo-Pakistani, foisted on Afghanistan by a coalition of wealthy Arab financiers and renegade Pakistani generals and mullahs.

One million Afghans are starving to death this winter. Ethnic cleansing continues. Music, dance, chess playing, and kite flying are banned. Women are forbidden to work or study, or to go outside their houses without a male relative to escort them.

By March the Buddhas had been destroyed, erased by small-arms fire, light artillery, mines, and explosives, according to the proud pronouncements of the “Emirate.” Dir ayah, dorost ayah, the Hazaras say. “Later it may be better.”

The dharma teaches us of impermanence, and the story of the Buddhas of Bamiyan is a perfect lesson. But it is a lesson sad beyond all telling.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.