The Serenity Prayer

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.

Jill: I started drinking before I got involved with Buddhism.

Rose: We were both trying to become yoga teachers at a center in the East Coast. We had to stop drinking and not eat meat.

Jill: And then our future Buddhist teacher came and turned it all around. He was invited to talk there. It must have been ’70 or ’71. I noticed he smoked and drank, and I was thrilled.

Rose: And that was just how I grew up. Everyone in my family drank. I never even thought about it. Drinking was normal. In my social background, it was the way people dealt with feelings. So I didn’t get into Buddhism to figure out anything about my drinking. I got interested in following a spiritual path when I realized that there was something to karma. I had had an abortion.

Jill: We were already close friends. And around this same time, my sister killed herself. She was an alcoholic. My mother was an alcoholic.

Rose: I started to practice. But I was also drinking. And my drinking was out of hand. I knew it was out of hand, but I didn’t care.

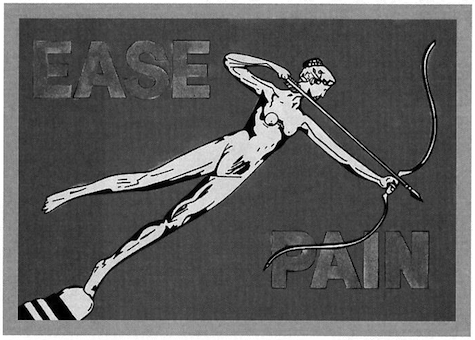

Jill: Early on I did a three-week retreat and did not drink. But when I came out, I started to drink heavily. That started a whole cycle that just escalated. And I did feel that I had license to drink. Certain kinds of celebrations ritually incorporated eating and drinking. Drinking lessons were a part of these celebrations and were really an effort to introduce mindfulness.

Rose: I think our teacher was dealing with a lot of people who had ideas about being “pure” and that much or the drinking element in our community was his way of getting people to be a little more earthy and wild. The wildness already among us came from acid and fantasizing—a cerebral wildness. The drinking lessons were about discipline. I mean real discipline. At the time, I thought that getting totally drunk was expanding my consciousness. But I really wanted a discipline. I know that now. I didn’t know that then.

Jill: I had just finished my prostrations. And someone said to me, “You’re drinking too much.” And I said, “No, you’re wrong. What I’m doing is right. This is the path. You can’t make those distinctions. ” That was my attitude. And I used that for a long time. Now I’ve been sober for ten years.

I still see Buddhists interpreting their addictions the way I used to—you know, “It’s all empty. Everything is emptiness.” Back then, that was my concept. And then using that to not pay attention to what is really happening. To use dogma to be irresponsible. I actually convinced myself that drinking was a great way to kill the ego. I wished I could be fearless—that whatever the state of my mind, I could accommodate anything, everything.

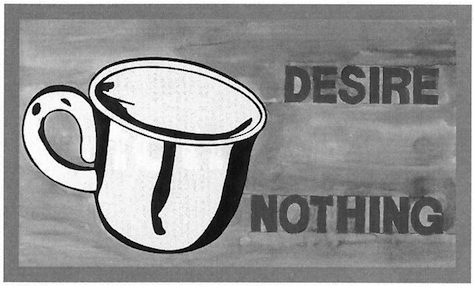

Rose: In Vajrayana the ideal that is constantly presented is that a truly realized yogi can transform poison into medicine. That relates to the absolute. Eventually I discovered I could not do that, which would have happened sooner or later. I was an alcoholic. In AA I discovered how to work with discipline on a relative level. There didn’t seem to be any encouragement among the sangha to go to AA. In fact, there was a subtle discouragement—this was a theistic thing to do. Looking back, I see that I was struggling with that belief. It could have been any belief. No one wants to admit that they are an alcoholic, and no one wants to go to AA.

Jill: But when you admit powerlessness, then you become responsible and you do have choice. Before you can admit that, you keep trying to manipulate how to drink and trying to make it all okay, and you keep hitting a wall, and that experience is a real experience. I’m limited. I cannot drink. This first step—admitting powerlessness over alcohol and that your life has become unmanageable—is like an absolute, like emptiness, and it’s a real experience. The rest of the steps are the path, you know, the relative truth.

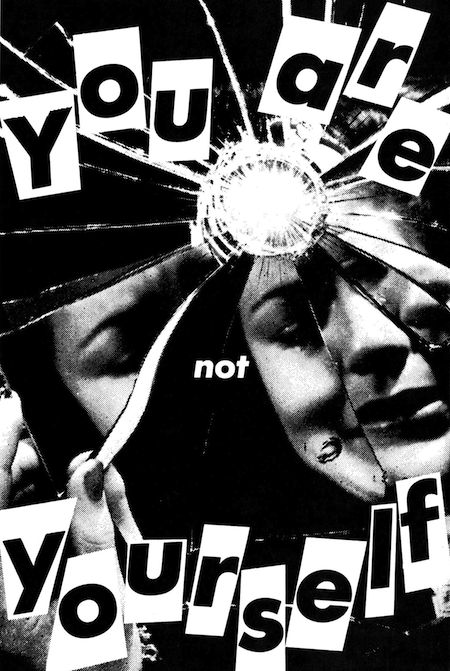

Rose: When I stopped drinking, it meant that I actually had to feel something that I did not want to feel. In Buddhist teachings, there is so much talk about absolute truth, but where is the connection between that and experiencing the unwanted mess of your life? The middle step is getting into the dirty stuff. Getting your hands dirty. Once you start really relating to your feelings, then it’s very hard to tell what is right and what is wrong. You can’t be dogmatic about feelings. You can only work it out—or not. Each moment that you yourself are in a crisis, you only have you yourself to figure it out. So all the years of doing sitting—that actually begins to mean something. You can stay with it. Not abandon yourself.

Jill: I had a very solid sitting practice when I first got involved in Buddhism. It helped end an eating disorder and really had a pacifying effect on me. And then, when I got into Vajrayana, I managed to think that I could handle all the poisons. At a certain point, I went over the edge. I couldn’t work anymore. I went into detox in ’82 and then started going to AA.

Rose: I had been in detox. But I had a really bad drinking problem. I never really thought that I could get over it. When I moved away from home to another community, I did not feel anyone could understand what I was going through. It was very lonely. And I started going to AA. I did ninety meetings—ninety days. I just did that. I had one slip. But the meetings were what helped. It was the first simple thing that ever happened in my life. Don’t drink and go to meetings. I didn’t have to figure anything out. I didn’t have to have any intellectual understanding. The simplicity of not drinking was like practice: you either just do something or you just don’t do something. And your feelings around that, or the convenience of the circumstances, is not what defines whether you do it or not. You have a structure, a program, like when you go on retreat. You get up and do it whether you like it or not, whether you want to or not, whether you’d rather stay in bed or not. AA actually taught me how to do that. Not drinking is a dharmic vow.

Jill: Our teacher encouraged sangha members who were in recovery to start their own support group. And he said that in the West people use alcohol to medicate themselves and to run away and to hide. He said that people who are addicted have to stop. At least, for a while. Because he also warned about labeling yourself, with any label. A lot of Buddhists question that—that the person in recovery is always labeling herself an alcoholic.

Rose: My response is “Well, just because you don’t label yourself an alcoholic, it doesn’t mean that you don’t still get really drunk when you drink.” Most people are not enlightened siddhas. The power of the mind is not great enough to overcome the relative effects on our bodies of what we ingest.

Jill: He used to say that you could drink again if and when you realized “one taste.” The idea there is that you are not getting off on anything. So that means there is no attachment to drinking or not drinking.

Rose: But that wasn’t held out as a taunt, or a challenge. He always said you have to figure things out for yourself. When you start to discover who you are, then there is just “my” reality. It’s up to me to understand it and try to be responsible. The more you practice, the more you realize, I have the power to be in my life. If any master that I really respected said to me, “You have to take a drink,” I would say, “Well, I really don’t think that I will.”

Jill: I feel the same way, that I have to take responsibility for my own life. Before, I might have felt guilty about not participating in some aspect of the teachings, but now I feel confident in the decisions I make to stay sober.

Rose: I feel that our teacher would have been happy to see people who were able to get sober. He felt that he could help alcoholics, and I have to say he did help me. He knew all about desire, and about needing space. I drank for twenty-five years. I’ve been sober for nine and a half years. Now I understand that when we say in AA, “We realize that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity,” that when I sit down on the cushion, that’s exactly what I’m doing. I am asking for a power greater than myself to restore me to sanity. I am allowing the saner part of myself to take over. I’m inviting some other kind of space in.

Jill: When we say, “God grant us the serenity…,” for me, it means conscious contact. It means, from a Buddhist view, the willingness to acknowledge your basic goodness. In meetings, I actually feel my heart open. And feel unconditional acceptance. Sometimes I feel so unaccepting of myself and I come into a meeting and I hear people bearing their pain, and I just feel myself opening in ways that make me feel sane and good and feel that I belong in the world.

Rose: The normal injunction is “don’t complain”—whereas in AA meetings you can see that complaint is an expression of suffering, and therefore you can go deeper than the complaint. This is more helpful than just being told to “stop complaining.” Because you are actually suffering. And that is why you are complaining. And in AA, they understand that. They provide a lot of space for that. In the Vajrayana there is a lot of emphasis on being able to accommodate everything. But when it came to drinking, you would say, No, I cannot do this. I’m an alcoholic, and that territory has boundaries; it is not infinitely spacious. With AA I don’t have to pretend that I can handle everything that comes down the pike. I can’t. Sometimes meditation instructors just don’t get it, and they will tell someone, Just sit with it, whatever it is. Sometimes that is not the best approach. Or the timing might not be right. Because if you try to sit in the earliest stages of recovery, you are probably having about fifteen million times more feelings than the average person. People who are addicts or alcoholics are oversensitized to begin with. That’s why they medicate. They are people who came into this world with their nerve endings not cauterized. One of the accusations leveled at people in AA—even by people in AA—is that it perpetuates the “I am special” story. But I think that’s great. Why not? Everyone is special. That is why they say there are a variety of skillful means for a variety of people.

Jill: In the beginning of AA I was quite arrogant. I thought being a Buddhist was special. People were talking my-higher-power this and my-higher-power that, and I would be snickering. But meanwhile I was still drinking, so my specialness as a Buddhist got leveled in AA. And then the specialness of my alcoholism got leveled in Buddhism. And I had to deal with all these specialnesses. In AA we have an expression: terminally unique. You can be so unique that you can’t relate to anyone or anything and it kills you.

Rose: I think the whole idea of giving up your story is dogma. One of my (Buddhist) teachers often says: Feel the feelings and give up the story line. But you should hear the way people use that. They don’t even contact feelings because they obliterate the story line. You can still be very humble even though your own experience is unique. Special does not mean proud; it means accountable. Sometimes—and this happens a lot in AA—when you get very specific about what you are experiencing, it opens things up. There is something concrete and there is the space. When it’s too general, and too abstract, there’s no friction—no movement on the path. In AA, people tell their story; they get some help and they become accountable.

Jill: And that’s something we can get from AA and bring back to our community. And I feel Buddhism is going in that direction. More local dharma. Local—I mean, where you are. I still have this conflict. I still feel that if I were completely free I would be able to drink, when I wanted to. But I can’t do that. I have friends that use Buddhism to stay in denial, to not really open up and deal with all the messy stuff of their lives.

Rose: That’s what I like about being messed up. Nothing would happen otherwise. Nothing. When the phenomenal world becomes your guru, you get great feedback.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.