Destination Zero: Poems 1970-1995

Sam Hamill

White Pine Press: Fredonia, New York: 1995.

233 pp., $15.00 (paper).

Destination Zero is a selection of poems that according to their author, Sam Hamill, asks us to follow a “lifetime of learning to speak simply.” Hamill divides the book into five sections, each with its own coherence. By not organizing Destination Zero book by book, he has de-emphasized the record of literary milestones on the journey and focused us on the journey itself.

The epigraph to Destination Zero is from Basho: “The journey itself is home.” Home is destination zero, that way of being moment by moment so fully in and of the moment that one dwells nowhere. As a body of work, Hamill’s poems give voice to the rich tension of being oneself and no one, being home and uneasily in exile from that place where one already is.

I was a child of no country

but the country of the heart. I felt

the hands of the dead slide up

beneath my shirt.

And now, when I write or speak

there is dying in my hands, dying

to flavor my speech.

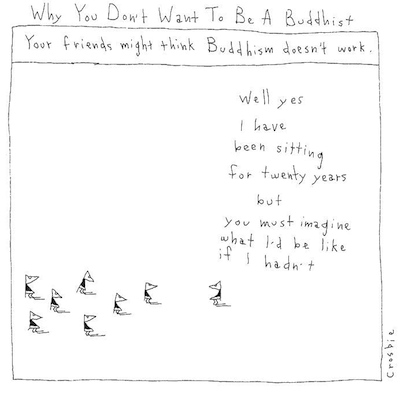

“A true poet,” Hamill has written, “is often faced with the difficult task of telling people what they already know and do not wish to hear.” Do we wish to hear that we cause pain? That we will die? That we live in a society of our own making, where the agreed-upon lies cause suffering for so many? Do we really wish to touch our pain directly? Hamill’s aesthetic calls for sincerity and directness of speech. Influenced by his study of Japanese and Chinese poets, Hamill’s poems reflect the qualities he admires in their verses – among them sabi, “an eloquent simplicity tinged with the flavor of loneliness,” and mono no aware, “a trace of the pathos of beautiful mortality.” Hamill draws his teachers from the West as well – Rexroth, Trakl, Seferis, Rilke, Roethke, McGrath – but his voice is his own. He heeds the advice of Basho not to follow in the footsteps of the masters, but to seek what they sought.

The dominant voice of this poet is that of one who mourns, and there is nearly always (as in the passage above) a quality of eros in the mourning. Loss“ ouches the poet; pain and grief and death move him to reconnect with the body of the earth, with his own body, a lover’s body, and the body of language. But the voice that mourns also wants to turn to praise, as in the richly beautiful long poem “Requiem”:

Tell me it isn’t fruitless, this moment

in which John Coltrane breaks

my heart from a phonograph, or that moment

long ago when I was lost in

Beethoven’s great Pastoral as the wind

swept away the desert endlessly.

As long as the tongue can open to the vowel,

as long as we can rise into

each day, just once, rise, and, rising

move the hand

to act, it remains for us to praise:

the fine red dust of Escalante,

light rain or mist of summer on the northwest coast,

almond groves of the northern San Joaquin,

the clarity of temple bells, Kyoto after rain.

And what of the other voices of Destination Zero? There is the more directly erotic voice of “Jubilate Sutra,” as well as the voice of transparent witness in “Black Marsh Eclogue,” speaking of the great blue heron:

He watches the heart of things

and does not move or speak. But when

at last he flies, his great wings

cover the blackening skies and slowly”

as though praying, he lifts, almost motionless

as he pushes the world away.

And there is the voice of anger, so painfully aware of the base uses of power: harsh words spoken to a beloved, physical violence, imprisonment, the spoilage of the earth. These are necessary poems, and one cannot fault them for their often blunt conviction. But when conviction is expressed in language and form that is too diffuse, as in “Blue Monody,” we are denied the poem’s full power – for a poem, however long, must be a succinct presentation that keeps its readers at full attention.

The best of Hamill’s poems hit the mark just so. Those that don’t, show us in their way how much struggle goes into the human work of bearing witness – the contradictions and the pain we must pass through in order to see, and to say,“what is.”There are poems of graceful form in Destination Zero. There are also poems that might allow more room for silence – the thing left unstated that speaks for itself, or the silence that heralds the unutterable. But the volume’s final poem, “What the Water Knows,” allows for both silence and speech at once:

What the mouth sings, the soul must

learn to forgive.

A rat’s as moral as a monk in the eyes

of the real world.

Still, the heart is a river

pouring from itself, a river that cannot

be crossed.

Margaret Gibson is the author of five books of poems, including The Vigil (Louisiana State University Press).

Image: Sam Hamill.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.