The trouble seems to have started last February, when Gomyo Kevin Seperic, a graffiti artist and Shingon monk affiliated with the Sitting Frog Zen Sangha in Phoenix, went public about a disagreement he was having with its abbot, Dogo Barry Graham, over Graham’s authority to teach. On his Hoodie Monk blog, Seperic said,

How many Sitting Frog Zen Sangha teachers does it take to change a light bulb? Not two, apparently. I’ve just been kicked out of the Sitting Frog Zen Sangha for asking Dogo to show me his inka. Huh….The cheese stands alone.

Soon, the Zen teacher Kobutsu Kevin Malone, with whom Seperic and Graham had both been affiliated, added a comment to Seperic’s post, in which he acknowledged that it was a “a serious error in judgment” on his part to have agreed to serve as Graham’s teacher without checking his credentials. “It has become increasingly apparent that Barry is in serious difficulty and that his words and actions have become increasingly erratic and delusional,” Malone wrote.

A few days later, it was Graham’s turn. “I have been the subject of some scurrilous rumor-mongering by a couple of former friends and colleagues,” he wrote on his own blog. Graham went on to allege that one of his accusers (he omitted the names) had been convicted of assault, and that the other’s own teaching credentials were fabricated.

The flurry of charges and counter-charges between Graham, Seperic, and Malone over inka—the authorization to teach in the Rinzai tradition of Zen—played out before an online audience, quickly blossoming into a fullon dharma smackdown that drew 171 partisan comments from Hoodie Monk readers. But a few found the whole thing painful to watch. The reader rg1313 commented:

The fact that three zen masters have to air there [sic] dirty laundry on blog sites seems a little childish. . . . You teachers are supposed to be role models for our practice not a buddhist sitcom.

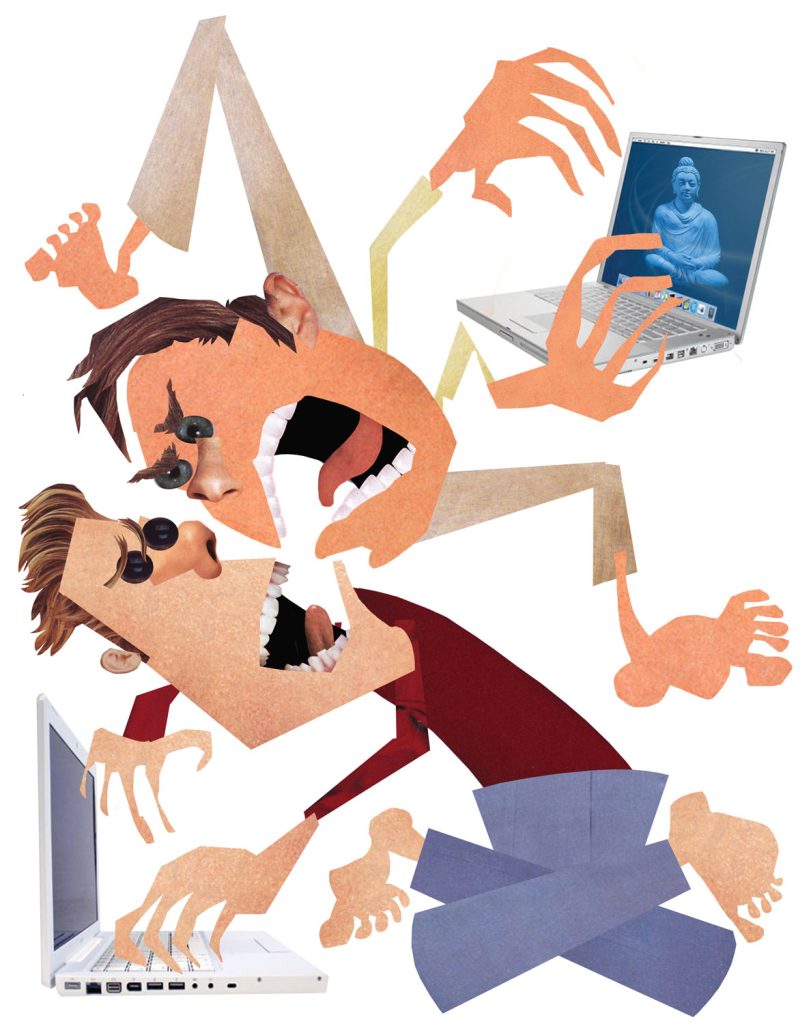

Indeed. If any newcomers exploring an interest in Zen had stumbled upon the fray, they wouldn’t have been inspired. With Buddhist virtues like compassion and right speech in short supply, the whole affair looked more like a schoolyard brawl than enlightened discourse between experienced dharma teachers and students. Unfortunately, the Sitting Frog squabble was hardly unique. In the era of Internet blogging and online forums with their unfiltered, rapidfire exchanges, disagreements among Buddhist teachers and practitioners seem to erupt out of nowhere.

American Buddhism has weathered its share of conflicts, including sex scandals, financial shenanigans, and power abuses.

It’s hardly news that Buddhists sometimes disagree—there is a long and colorful history of Buddhist teachers debating one another, often quite forcefully, over their understanding of the dharma. And American Buddhism has weathered its share of internecine conflicts, including sex scandals, financial shenanigans, and power abuses. What has changed in the past few years is that some Buddhists are now accustomed to casual online mudslinging and name-calling—in short, behaving just as badly as everyone else on the Internet.

“People say and do things online that they wouldn’t ordinarily say and do in person,” says John Suler, a psychology professor at Rider University, in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, who has studied computer users’ behavior for years. Buddhist or not, Internet users readily fall prey to what Suler calls the “online disinhibition effect.” The medium itself drives much of this acting out, he says. “People experience their computers and online environments as an extension of their selves—even as an extension of their minds—and therefore feel free to project their inner dialogues, transferences, and conflicts into their exchanges with others in cyberspace.”

One might suppose that Buddhists, with their mandate to realize no-self and manifest lovingkindness, would be able to navigate such pitfalls a bit more skillfully than most Internet users. But Suler, who has some familiarity with Buddhism—in 1993, he published a book titled “Contemporary Psychoanalysis and Eastern Thought”—isn’t surprised that teachers and students get carried away online.

“There’s a lot more narcissism in the community than we would expect or hope,” he says. “It’s a bit paradoxical that in a philosophy emphasizing the transcendence of self, some people are very preoccupied with self.”

Online, as in the real world, this self-regard often seems to fuel unbridled aggression. Consider this exchange from James Ure’s The Buddhist Blog, in which a reader identified as Twisted Branch commented:

Your lack of knowledge of authentic Dhamma teaching is astounding. It’s amazing you even have the courage to call this the “Buddhist blog.” All this crap you ramble on about has absolutely nothing to do with Buddhism. Your blogs are far more offensive to Buddhist tradition than any off-hand use of the term Zen. Please study authentic Buddhist teachings before claiming knowledge of Buddhism.

Two hours later, Ure responded:

Twisted Branch: If you read in my profile I don’t claim to be a teacher. I’m just trying to make sense of things as best I can. I’m sorry that you find my blog offensive but I must say that you’re in the minority. Maybe you should use your blog to teach the Dhamma the way you understand it since you seem to know it all. Rather than come onto someone else’s blog and judge and insult them. Just a thought.

A few minutes later, Forest Wisdom chimed in:

Knowledge is one thing, and practice is wholly another. If someone who supposedly “knows” acts like a jerk, and someone who doesn’t “know” but makes every effort to practice responds with humbleness and respect (as I commend James for doing). . . Hmmmm, who are people going to listen to? I honestly and truly wish you peace, Twisted Branch, but please, get over yourself.

That afternoon, Twisted Branch was contrite.

Maybe I was a bit harsh, I am truly sorry for my offensive comments. Sometimes I get frustrated with the western understanding of Buddhism. I would use my blog to teach Dhamma, but it is not the place for teaching. I will no longer use this forum as a place to vent personal frustrations. Thanks also to forest wisdom for your wise perspective.

Twisted Branch had a point, though. In cyberspace, we can craft whatever persona we choose and call our blog whatever we want, and Buddhist bloggers often inflate their experience and understanding. Shinge Roko Sherry Chayat Roshi, a Zen teacher who serves as spiritual director of the Zen Center of Syracuse, likens this behavior to online personal ads, where people have been known to misrepresent themselves (to put it charitably).

“People who purportedly are teachers—whether they’ve been given transmission or not—are seen as Zen authorities online,” she says. “Sometimes students get swept into currents of basically malevolent speech. How can that be what the Buddha taught? I’m very concerned about it.”

“There’s something about the social distance that happens on the Web,” concurs James Ishmael Ford, a Zen teacher and blogger. “Anybody with a keyboard is instantly allowed to present whatever they’ve pulled out of their butt as if it were the dharma. There’s some ugly stuff out there. There’s massive misinformation, and there’s an amazing amount of ego wrapped in opinion.”

Not every Buddhist-themed website is a vehicle for vicious personal attacks, of course. Many teachers and sanghas have found the Internet to be an effective way to post text, video, or audio links to teachings that would otherwise be unavailable to people living far from practice centers. Examples include the online presence of John Daido Loori’s Mountains and Rivers Order; the pages of the Insight Meditation Society and the Spirit Rock Meditation Center; the Sravasti website of Venerable Thubten Chodron; and Shinge Roshi’s own Zen Center of Syracuse website. In most cases, these sites don’t solicit feedback, but when they do, participants more often see themselves as members of a community, and they may even know each other offline. The discourse accordingly tends to be civil and supportive.

“Anybody with a keyboard is instantly allowed to present whatever they’ve pulled out of their butt as if it were the dharma.”

Ken McLeod, a Los Angeles–based teacher, also manages to maintain a general sense of civility on the eight different websites connected with his Unfettered Mind organization, but he doesn’t overestimate the social potential of the Internet. “People don’t realize they’re relating to a machine,” says McLeod, who was one of the first to launch a social networking site for Buddhists. “Something pops up on their screen that offends them, and they scream at it.” He thinks people need to wake up and take charge of their interactions with a technology that can alienate as well as unite. “Use the tools that implement what we want them to do, not do what they want us to do,” McLeod urges.

Another factor accounting for online rancor may be blogs and teaching websites that promote an in-your-face attitude, says McLeod. “When people are meeting you through your website, that’s their first contact with you, and it had better represent you,” he says. Blogs and discussion forums open to the entire Internet encourage comments from total strangers, and while this often leads to cordial discussion, it also attracts people dedicated to having the last word—the know-it-alls who delight in denigrating others while touting their own dharmic understanding.

Brad Warner, a Soto Zen teacher and the author of several books, has seen this firsthand. In a recent thread on Warner’s Hardcore Zen blog, for example, a reader advised Warner to

shut the fuck up and go meditate. if you are really a buddhist monk you wouldn’t waste your time on a fucking internet forum. don’t judge others, judge yourself in meditation.

Interestingly, the reader’s tone mirrors some of Warner’s own posts. He has, for example, called the prominent Soto Zen teacher Dennis Genpo Merzel Roshi “a scumbag” and “a slime ball” in critiquing Merzel’s controversial Big Mind program. Warner’s posts often draw hundreds of comments from readers, some of whom throw insults at each other—and at Warner—with abandon. Warner justifies his own outrageous rhetoric as an unconventional way of making a serious point, tracing his writing style to his roots as a 1980s punk-rock musician and journalist. “That’s the way you wrote in punk zines, and it was understood within that community that you called a friend a scumbag and everybody would laugh about it,” he says. (Warner and Genpo Roshi, it should be noted, are not friends.)

For some readers, Warner contends, these barbed public exchanges help to deflate idealized perceptions of Buddhist teachers, and that’s a good thing. If someone rejects Buddhism after stumbling across an online debate, “They’re walking away from a fantasy of Buddhism,” he says. “That’s O.K. They’re not going to find that anyway, so it sort of speeds up the process.” But it is really necessary to drive them away with a stick?

Shinge Roshi takes a dim view of the whole dharma-teachers-with-attitude phenomenon. “If you see ‘Buddhist teachers’ getting caught in an angry give-and-take, they’re not teachers—or if they are, they never should have been given transmission,” she says. “How can you cast these terrible aspersions on others without bringing shame on your own lineage? That’s really what I’m struck by—that people seem to be oblivious to the karmic results of their actions and their words.

“Karmically, I think it’s quite dangerous,” Shinge Roshi continues. “It is easy to be swept away. People can get into righteous states of indignation very quickly. When there is no one looking in their eyes, when there is no face across from them seizing up with horror, it’s easy to continue.”

James Ishmael Ford is more sanguine about Buddhism’s move to the Internet, especially when taking the long view. “I think that, on balance, more good will come out of this than harm,” he says. “I think it’s bad for many of the people participating, I think a level of misinformation is ubiquitous, and I think it’s very exciting.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.