Ocean of Wisdom: His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama by Rajiv Mehrotra, 30 minutes, available from PBS Home Video (800) 328-7271.

Compassion in Exile: the Story of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, a film by Mickey Lemle, 60 minutes, Lemle Pictures, Inc. (212) 736-9606.

Heart of Tibet: An Intimate Portrait of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, by David Cherniack and Martin Wassell, 60 minutes, available from Mystic Fire Video (800) 292-9001.

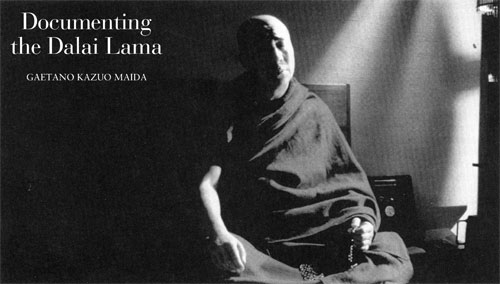

Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet, no longer needs an introduction. After he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, the media made him a familiar figure who, in maroon robes, speaks eloquently on behalf of his country and for world peace, and who is inevitably identified as a simple Buddhist monk. But like most famous people, he is poorly served by superficial attention, and we’re left with the disturbing possibility that the public portrait is intended to limit his significance.

The Nobel Prize was awarded to the Dalai Lama for his nonviolent approach to the Chinese takeover and continuing destruction of Tibet. His commitment is not merely the philosophical stance of a gifted individual, but the embodiment of the cultural ideal of his Buddhist heritage and practice. He is considered by his followers to be the living manifestation of Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and he remains unfailingly without bitterness toward the Chinese. What he represents (and has spent his life training for) is the unique combination of statesmanship and liberation from negativity and illusion. He is foremost a spiritual leader, not a politician.

Film offers tantalizing possibilities for probing a life. And when John Avedon, author of In Exile From the Land of Snows (Random House, 1979), says (in Heart of Tibet) “the way His Holiness has safeguarded Tibetan culture and fought for the eventual freedom for his homeland … is the quintessential expression of his spiritual values,” we can begin to recognize the scale at which a biography of this Dalai Lama must be framed. The difficulty of examining a life as special as that of this Dalai Lama is revealed, however (in different ways and in varying degrees), in three recent films all subtitled to imply biographical depth.

The three films share much (too much, in fact): intimate scenes of His Holiness meditating, eating, (and inHeart of Tibet, brushing his teeth!), and repairing watches (his favorite hobby); the Dalai Lama leading initiations and events and giving blessings; the awarding to him of the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize; the same remarkable archival footage of the young Dalai Lama, the Chinese takeover and recent repression, and the perilous escape to India; and most of all, a clear and unquestioning reverence. All three amply detail the continuing oppression of Tibetans in their homeland with compelling reports and interviews.

Where they differ is in how each attempts to bring this remarkable man into focus as an individual. Ocean of Wisdom: His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama by Rajiv Mehrotra, at only thirty minutes, has to be content with describing (using Peter Coyote’s concise narration) the recent history of Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s prominent public role in it. Opening and closing with a closeup of His Holiness meditating, this good introductory short also imparts a primer on Buddhist belief and history, and curiously opens a crack on Tibetan society, beyond the current mythologizing, when we hear the Dalai Lama briefly describe (with superfluous English subtitles) some monasteries as landlords with less than solid Buddhist practice.

Mickey Lemle’s Compassion in Exile: the Story of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is a beautifully shot sixty minute film that features a wonderful (if overused) Philip Glass score, and is also enriched by a haunting Tibetan song. We begin to get a sense of the Dalai Lama as a person through interviews with two of his brothers and a sister, and in an interview with his friend and former tutor, Heinrich Harrar, who says the Dalai Lama “was like any other boy, but he had no chance to be like any other boy.” His Holiness himself tells that “when I saw other boy and girls playing, I very much wanted to join them.” We also hear his revealing memory of his meetings with Mao, and there is a sense of directness in an on-camera interview used throughout the film. Among other unique scenes, an odd sequence with a British woman wearing a Phil Silvers/Sergeant Bilko T-shirt, telling of its being mistaken in Tibet for a portrait of His Holiness, is a questionable inclusion, but there is an inspired use of drawings to illustrate the discovery of the two year-old Dalai Lama. In this film too, his story is inextricably entwined with that of his country.

After an almost incongruous introduction by Jimmy Carter, Heart of Tibet: An Intimate Portrait of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, David Cherniak and Martin Wassell’s sixty-minute video, finds an effective form using the Kalachakra mandala initiation in Los Angeles as a framing device in cutaways throughout. There are extraordinary views of this event including the preparation, the dances, the meticulous ongoing work on the sand painting, and His Holiness in the role of Vajra master of the initiation. We hear him responding to the reporters’ questions (even the provacative “Who are you?”), and we see him speaking at public gatherings and privately to a group of Tibetans.

The closest we come to sensing the person is through interviews with two Americans long identified with the Dalai Lama, John Avedon and Tibetologist Robert Thurman. Avedon suggests that we in the West don’t really have a basis for evaluating a monk in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Thurman gives us simple descriptions of enlightenment and the nature of suffering, and then offers an answer to our open question: “He is a head of state, a simple monk, a simple human being, a great master, a great philosopher, a Tibetan, a freedom fighter, an office bureaucrat… totally ordinary. The key to that famous ‘I am a simple Buddhist monk’ statement is that it’s totally sincere, but it’s totally flexible, and he can be a very complex being when it’s to the benefit of other beings.”

What’s missing in all of these films are the details that would help define the Dalai Lama as an individual and counter the media’s glorification of him as an aid to the cause of Tibetan nationhood: namely, his Buddhist practices and the relationships with his several spiritual teachers; his views of his family (one of his brothers was recognized as a reincarnated lama before the discovery of the Dalai Lama). None of these films goes beyond the (misguided) attempt to promote him as a Buddhist pope. The irony is that a truly courageous and complete portrait would best serve the Tibetan cause, precisely because what makes the Dalai Lama unique is his embodiment of those spiritual values that so singularly define Tibetan culture. To concentrate on his political role and Tibetan nationalism diminishes the very dimension of the man and his country that most compels our support.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.