In many ways, the history of Buddhism is the history of translation. In many ways, the Buddha’s most important instruction took place when he forbade two Brahmin converts from turning his teachings into chandas. Whatever that term might precisely mean, it seems to be a method of chanting similar to that used for the Vedas. The Buddha warned the two monks that to versify his words in that way would violate the Vinaya. Instead, his disciples were to teach the word of the Buddha in their dialect, to teach in the vernacular. In other words, he required his monks to translate.

One might argue that this was the most significant factor in Buddhism becoming a world religion. This does not mean, however, that Buddhism, from the beginning, did not need its own language. That language, called Pali, often mistakenly claimed to be the language that the Buddha spoke, is an artificial language, a kind of Church Latin, invented so that monks and nuns from different parts of India (with its many languages and dialects) could read, recite, and write in a single language. In other words, it’s a translation.

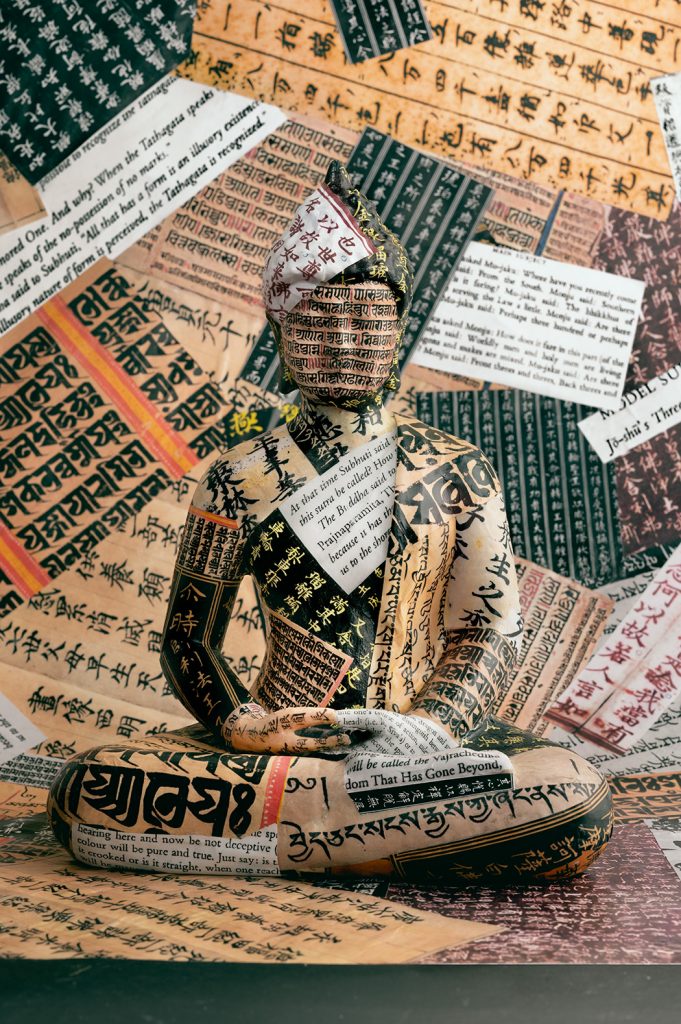

The history of Buddhism is filled with remarkable feats of translation. Consider Buddhayashas, who recited the entire Vinaya from memory so that it could be translated into Chinese, or Xuanzang, who returned to the Tang capital with 657 texts after a perilous journey through Central Asia, or Amoghavajra, who traveled from Xian to Sri Lanka to retrieve tantras. Indeed, the translation of Indic Buddhist texts into Chinese and then into Tibetan constitutes two of the most remarkable and consequential translation projects in human history. It is from the study of these translation projects that we learn so much about Indian Buddhism, things that would otherwise remain lost in the mists of time, while raising questions that we still ponder, such as whether the early translation of a text into Chinese somehow indicated its importance in India. There are texts for which we have only the titles and texts even whose names do not survive. As translation continues to our own time and place, we ponder a new future of artificial intelligence that will allow us to eventually translate every Buddhist text into every language, living or dead. The implications are profound. What discoveries await us? What perils loom? The Tibetan verb that we translate as “translate” literally means “change.”

The three major Buddhist canons—Pali, Chinese, and Tibetan—are each different from the other. The Pali canon is said to be organized in the order recited by Upali and Ananda at the First Council shortly after the Buddha passed into nirvana. The famous Tibetan Kangyur (“Translation of the Word [of the Buddha]”) and Tengyur (“Translation of the Treatises”) are composed primarily of works of Indian origin. The Chinese canon includes both Indian and Chinese works. Today, advances in artificial intelligence raise the possibility of a fourth canonical language—English—and a fourth Buddhist canon.

But why would we want to do this? Is it because every text needs to be translated? We used to say that, perhaps because we knew it was impossible to do so. Now, it seems possible. But still, we wonder why. Is it because we expect to find the fifth noble truth? By this time, as we approach two centuries of translating Buddhist texts into European languages, many would argue that there is no fifth noble truth, no important philosophical doctrine that we are not already aware of.

After centuries of translation, is there anything significant left to discover? In a sutra, the Buddha shoots a ray of light from the tuft of hair between his eyes, illuminating a thousand universes. The scholar of Buddhism shrugs. That again? Admittedly, these are rude questions. Let us turn to a question that is not so rude: Did anyone ever read the entire canon? For my purposes here, I will use the term to refer to the Tripitaka, broadly conceived, excluding commentaries, whether Indian, Chinese, or Tibetan. At the Sixth Council, held in Yangon in Burma in 1956, a monk named Mingun Sayadaw recited the entire Pali canon from memory. Does that mean that he also read it?

In Tibetan Buddhism, Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) devoted years to studying the canon. But his reading retreats seem to have focused primarily on shastras (Indian philosophical treatises) rather than the sutras. These works shaped his monumental Lam rim chen mo (Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path). The monasteries of the Geluk, the sect he founded, based their curricula on textbooks derived from his works, moving even further from the sutras. This fixation on textbooks to the exclusion of the founder’s own works became such a source of displeasure to the Dalai Lama that in 1975, he published a two-volume set whose Tibetan title means “the lord’s (that is, Tsongkhapa’s) statements on the view.” So that Geluk monks would have no excuse for not reading the words of Tsongkhapa, he had hundreds of copies printed, giving them to all of the monks studying at the relocated Ganden, Drepung, and Sera monasteries in South India.

What effect does the translation of the Buddhist canon have on the Buddhist literature of the target language? What happened in China and Tibet, for example, when the Indian canon, however defined, was translated into Chinese and Tibetan? Let’s begin with China.

By the 5th century, most of the famous Indic sutras had been translated into Chinese, including the Lotus Sutra, the Nirvana Sutra, and the Perfection of Wisdom corpus, by such famous translators as Kumarajiva, Buddhabhadra, and Dharmakshema. Over time, however, new texts began to emerge—works that presented themselves as Indian but were, in fact, of Chinese origin. These scriptures would become central to schools like Chan and Tiantai. Scholars call these texts, which include the famous Awakening of Faith, “Apocrypha.”

Advances in artificial intelligence raise the possibility of a fourth canonical language—English—and a fourth Buddhist canon.

The translation of the Tibetan canon is famously divided into two periods: the “earlier dissemination” and the “later dissemination,” the former beginning during the reigns of three great dharma kings of the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries and concluding with the assassination of the not-so-great king Langdarma in 842, ending the Tibetan monarchy forever. Traditional accounts state that this plunged Tibet into the “Age of Fragments.” According to partisan histories, this period ended with the work of translators like Rinchen Zangpo, who returned to Tibet in 987 after thirteen years of study in India. The “new translations,” especially of the tantras, would be edited, expanded, and organized into the form we know today by Buton in 1351.

It was around the time that the canon of translations of Indic texts was reaching its present form that other Indian texts began to be translated into Tibetan, works that, according to their translators, had not been brought from India but composed in Tibet by an Indian master. These are the famous terma, the “treasures,” said to have been composed by Padmasambhava in the 8th century and buried around the country to be unearthed when Tibetans were spiritually prepared to receive them. Often dismissed by the three “new translation” schools as forgeries, they were accepted as canonical by the “old translation” school, the Nyingma, as the words of the Buddha, or at least of the Second Buddha, Padmasambhava. And so we see again that when the Indic canon has been translated into the host culture’s language, apocrypha begin to be composed.

The translation of a Buddhist canon, then, now, and even in the future, is a massive undertaking, requiring the motivation, resources, erudition, and effort of so many. What happens when the task is done? As just noted, when the task of the translator is completed, apocrypha soon appear. But what becomes of the translated canon itself? Perhaps surprisingly, perhaps not, one of the poignant benefits of the heroic efforts to translate the canon is that it no longer has to be read. Tibetan temples typically have the volumes of the Kangyur and Tengyur neatly wrapped and placed in wooden slots on the altar on either side of the central image, serving as the dharma that one bows down to when one recites the refuge formula. One of the rare occasions when the Tibetan canon is read is in a time of crisis. When I was living at Drepung Monastery in southern India many years ago, there was a drought that threatened the crops of the local Tibetan farmers. The monks took the volumes of the canon down from the altar, with each monk holding a single volume on his right shoulder. They then made a procession, walking in single file around the fields in a clockwise direction. They eventually returned to the temple, where each monk sat down, opened his volume, and began readingaloud—actually shouting aloud—creating a cacophony. When the entire canon had been recited, the monks wrapped up the volumes and returned them to the altar.

And so before we create a new canon, we might pause to consider the fate of the old ones. In Tibetan temples, the canon is displayed as a sacred symbol of the dharma, frequently used in rituals to invoke blessings. The Goryeo canon in Korea was believed, sadly mistakenly, to protect the kingdom from invasion, its presence thought to ward off enemies. In Japan, turning a rinzou—a rotating cabinet filled with scriptures—generates merit equal to reading the entire canon. Today, the Tibetan Kangyur and Tengyur, consisting of more than 195,000 printed sides, have been digitized and saved on a flash drive designed to be worn as an amulet—technology preserving the canon as both text and talisman. All of this would suggest that when the canon has been translated, we no longer have to read it. It becomes a means for magic.

Chinese and Tibetan apocrypha began to be composed after many Indic texts were translated into Chinese and Tibetan. And so perhaps the translation of the Buddhist canons into English is not an end but a beginning, a renaissance of modern language apocrypha.But how would one do that? In a passage from the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya, Upali asks the Buddha, “Reverend One, in the future, monks will appear who have imperfect memories, feeble memories. If they do not know in which place, village, or town which sutra was taught and which training rule was promulgated, how are they to supply them?” The Buddha replies, “Upali, those who forget the place’s name, et cetera, must declare that it was one or another of the six great cities or somewhere where the Tathagata stayed many times. If he forgets the name of the king, he must declare it was Prasenajit; if the name of the householder, that it was Anathapindada; of the lay sister, that it was Mrigaramata.”

Where does this leave the Buddhologists? Are we doomed to push book carts through the Library of Babel? Or, perhaps more hopefully, we will find ourselves transported to Jorge Luis Borges’s planet Tlön, a world where the metaphysicians do not seek the truth but instead “a kind of amazement”; metaphysics for them is a branch of fantastic literature. On the planet Tlön, he writes, “The dominant notion is that everything is the work of one single author. Books are rarely signed. The concept of plagiarism does not exist; it has been established that all books are the work of one single writer, who is timeless and anonymous.”

With the possibility of translating the ancient corpus of Buddhist sutras by artificial intelligence, a new day of apocryphal sutras dawns, each with the original’s anonymity. But let me close by suggesting that the production of apocryphal sutras has already begun. In fact, it started long before anyone in this country knew how to pronounce tathagatagarbha. It was in 1955 in Berkeley, California. The author was Allen Ginsberg.

♦

Adapted from a lecture at the AI and the Future of Buddhist Studies conference, UC Berkeley, October 18–19, 2024.

A New Canon?

“Sunflower Sutra” by Allen Ginsberg

I walked on the banks of the tincan banana dock and sat down under the huge shade of a Southern Pacific locomotive to look at the sunset over the box house hills and cry.

Jack Kerouac sat beside me on a busted rusty iron pole, companion, we thought the same thoughts of the soul, bleak and blue and sad-eyed, surrounded by the gnarled steel roots of trees of machinery. The oily water on the river mirrored the red sky, sun sank on top of final Frisco peaks, no fish in that stream, no hermit in those mounts, just ourselves rheumy-eyed and hung-over like old bums on the riverbank, tired and wily. Look at the Sunflower, he said, there was a dead gray shadow against the sky, big as a man, sitting dry on top of a pile of ancient sawdust—I rushed up enchanted—it was my first sunflower, memories of Blake—my visions—Harlem and Hells of the Eastern rivers, bridges clanking Joes Greasy Sandwiches, dead baby carriages, black treadless tires forgotten and unretreaded, the poem of the riverbank, condoms & pots, steel knives, nothing stainless, only the dank muck and the razor-sharp artifacts passing into the past—and the gray Sunflower poised against the sunset, crackly bleak and dusty with the smut and smog and smoke of olden locomotives in its eye—corolla of bleary spikes pushed down and broken like a battered crown, seeds fallen out of its face, soon-to-be-toothless mouth of sunny air, sunrays obliterated on its hairy head like a dried wire spiderweb, leaves stuck out like arms out of the stem, gestures from the sawdust root, broke pieces of plaster fallen out of the black twigs, a dead fly in its ear, Unholy battered old thing you were, my sunflower O my soul, I loved you then! The grime was no man’s grime but death and human locomotives, all that dress of dust, that veil of darkened railroad skin, that smog of cheek, that eyelid of black mis’ry, that sooty hand or phallus or protuberance of artificial worse-than-dirt—industrial—modern—all that civilization spotting your crazy golden crown—and those blear thoughts of death and dusty loveless eyes and ends and withered roots below, in the home-pile of sand and sawdust, rubber dollar bills, skin of machinery, the guts and innards of the weeping coughing car, the empty lonely tincans with their rusty tongues alack, what more could I name, the smoked ashes of some cock cigar, the cunts of wheelbarrows and the milky breasts of cars, wornout asses out of chairs & sphincters of dynamos—all these entangled in your mummied roots—and you there standing before me in the sunset, all your glory in your form! A perfect beauty of a sunflower! a perfect excellent lovely sunflower existence! a sweet natural eye to the new hip moon, woke up alive and excited grasping in the sunset shadow sunrise golden monthly breeze! How many flies buzzed round you innocent of your grime, while you cursed the heavens of the railroad and your flower soul? Poor dead flower? when did you forget you were a flower? when did you look at your skin and decide you were an impotent dirty old locomotive? the ghost of a locomotive? the specter and shade of a once powerful mad American locomotive? You were never no locomotive, Sunflower, you were a sunflower! And you Locomotive, you are a locomotive, forget me not! So I grabbed up the skeleton thick sunflower and stuck it at my side like a scepter, and deliver my sermon to my soul, and Jack’s soul too, and anyone who’ll listen,—We’re not our skin of grime, we’re not dread bleak dusty imageless locomotives, we’re golden sunflowers inside, blessed by our own seed & hairy naked accomplishment-bodies growing into mad black formal sunflowers in the sunset, spied on by our own eyes under the shadow of the mad locomotive riverbank sunset Frisco hilly tincan evening sitdown vision. Berkeley, 1955

From Collected Poems 1947–1997 by Allen Ginsberg © 2007 Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.