Well ol’ Buddha was a man

And I’m sure that he meant well,

But I pray for his disciples

Lest they wind up in Hell.

The Imperials’ “Oh Buddha” was a smash hit on the Southern Gospel charts in the late ’70s, and driving past the prominent white-steepled Baptist church of Lexington, Virginia, one might expect to hear it still playing on the radio. This small Appalachian town is the burial place of Robert E. Lee and his horse, Traveller, as well as Confederate general Stonewall Jackson (though his left arm is buried elsewhere). But the ghosts of these men who saw so much violence aren’t fully laid to rest. The Civil War can still stir passions and provoke heated arguments among the folks here, and among the potters, weavers, and woodcarvers, and the church stalls selling fried chicken and barbeque, the Sons of Confederate Veterans in their gray uniforms are still one of the most popular booths at the spring fair.

For a great many Southerners, Jesus may be Lord (and Elvis still King), but a closer look at Lexington reveals a new element Stonewall Jackson never encountered. “What does ‘Bodhi’ mean?” asks a local veterinarian. “I’ve treated four different dogs with that name this year.” Sifting through the stacks of Kenny Rogers and Oakridge Boys CDs in a downtown thrift store, you’ll also discover titles like “Mantra Mix” and “Gyuto Monks Chant.” But the real surprise is waiting just out of town in Rockbridge County. Turn right onto Broad Creek Church Road across from the faux ’50s restaurant, and you’ll be on the trail of something quite unexpected. Back in the woods a couple of miles, past foraging woodchucks and whitetail deer, you’ll come up over a hill and suddenly lay eyes on a gleaming white-and-gold Tibetan stupa. Quietly tucked away in the Shenandoah Valley lies Bodhipath Buddhist Philosophy and Meditation Center, a thriving temple that is home to Shamar Rinpoche, one of the highest lamas in Tibetan Buddhism’s Kagyu tradition.

In the last thirty years, the South has experienced an explosion in the number of Buddhists and Buddhist centers. From the Bluegrass to the Lone Star, every state in the South now boasts an array of Buddhist groups. The curious can investigate everything from Rinzai Zen to Chinese Pure Land to Theravada; virtually every form of Buddhism that has a presence in the traditional American Buddhist hotspots of Hawai’i, California, and the Northeast can be found somewhere below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Though the visibility of Buddhism is much greater today, the seeds of the South’s growing Buddhist communities were planted decades ago. And true to the South’s heritage of social turmoil and soulful endurance, Buddhism’s roots in the region lie in soil both tragic and hopeful. During World War II, Arkansas had the largest number of Japanese-American concentration camps, where the mostly Buddhist prisoners clung to religion to ease their suffering. Jack Kerouac spent time in the mid-1950s meditating, reading about Buddhism, and dreaming of a “rucksack revolution” in the piney woods of Rocky Mount, North Carolina. In the late ’50s and ’60s, Thomas Merton was reading and writing about Zen in his Kentucky Trappist monastery, while Thich Nhat Hanh convinced Martin Luther King, Jr., to oppose the Vietnam War, and was later nominated by King for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1966 Washington, D.C. became the home of the first Theravada temple in North America.

By the time of the Dalai Lama’s first American visit in 1979, Buddhism had become acceptable enough that the mayor of Houston declared His Holiness an honorary citizen. Nowadays no one even blinks when Tibetan monks pour sand from a “healing mandala” into the Potomac to commemorate the September 11 attack on the Pentagon. But in some ways, the more things change, the more they stay the same. In the wake of September 11, one can find bumper stickers in Mississippi with the slogan “Firearms: Now More Than Ever,” and Christian fish symbols are hardly rivaled by Tibetan double-fish motifs. The South has been both a rich stew of many cultures—including Gullah-speaking Sea Islanders in Georgia and caber-tossing Scots in the Appalachians—and a fierce battleground of resistance against “outsiders,” led by soldiers fighting against the “War of Northern Aggression” or the likes of petulant baseball star John Rocker. And there have been many occurrences of blatant resistance to Buddhism and Buddhists, and hostility to Asian immigrants. The internment of Japanese Americans was hardly the last such incident. In the early 1980s, as Vietnamese refugees began to infiltrate the shrimp trade in Galveston, Texas and other Gulf cities, incidents of boat arson began to rise, and the Ku Klux Klan even hung a Vietnamese fisherman in effigy. Community methods of exclusion have become somewhat more sophisticated in the intervening years: in the past year, neighborhood residents used zoning laws to harass members of Vietnamese American Buddhist temples in Southern states as far apart as North Carolina and Florida. Of course, more violent intimidation is still an option: in April vandals struck a Theravada temple in North Carolina twice, spray-painting slurs on statues and buildings.

Immigration is one of the main sources fueling the proliferation of Buddhist groups in the South. Ever since immigration laws were relaxed in 1965, the South’s ethnic mix has included increasing numbers of Asian immigrants, especially Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Thais. Many are already Buddhists and seek to preserve their Old World traditions in their new homes. But an interesting parallel phenomenon exists whereby nonpracticing immigrants turn to Buddhism in America in order to reconnect with their Asian heritage. This occurs especially in areas where other Asian cultural elements are largely absent. So, paradoxically, many of the South’s Asian-American Buddhists are more observant than their counterparts in Asia.

Another unique facet of Dixie dharma is the contribution African Americans have made. Virtually all the well-known African Americans involved in Buddhism have originally come from the South, including Jan Willis, Ralph Steele, Joseph Jarman, Alice Walker, bell hooks, and Tina Turner. Unfortunately, this doesn’t mean that Southern sanghas are any more integrated than their Northern and Western counterparts. Asian Americans and European Americans largely attend separate groups with little interaction, while African Americans and Latinos must try to find a place as minorities in these communities or pursue a solitary dharma practice. The one exception is Soka Gakkai, which, as elsewhere in the country, has many African-American local leaders and members.

There are some promising signs of pan-sectarian cooperation, however. Isolated in the South, some Buddhist groups have formed loose networks to keep everyone apprised of local dharma happenings, such as the Ecumenical Buddhist Society of Little Rock, Dharma Memphis, and the Texas Buddhist Council. Most quirky of all is Ekoji Temple in Richmond, Virginia, a Jodo Shinshu Pure Land temple that also gives space to Vipassana, Kagyu, and Soto Zen groups. The Vipassana and Pure Land groups meet in the space downstairs, while the Tibetan and Zen groups each have their own second-story rooms. The differences in style couldn’t be more striking: the Vajrayana room is a riot of vibrant yellows, golds, and reds, with elaborate pictures of deities and Buddhas everywhere, while the Zen room on the other side of the wall is stark white, with just a small Buddha, a calligraphy scroll, and simple black cushions. The personalities of two great traditions are perfectly revealed through their furnishings. Despite the different tastes in interior design, however, there are some who attend more than one of the Ekoji groups. Perhaps from these small beginnings a greater understanding of the whole of Buddhism’s richness will begin to emerge.

As Buddhism has entered the South, some old patterns of religious life have reemerged. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, wandering Methodist ministers rode their horses in large circuits, preaching at a different church each Sunday. The interest in Buddhism far outstrips the number of trained teachers available in the South, so Buddhist priests and monastics are forced to travel long distances to provide services and instruction to outlying branch temples. Modern-day circuit riders such as Taitaku Pat Phelan may be based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, but any given weekend may find her as far afield as Virginia—in Roanoke, Richmond, or Virginia Beach—giving lessons in zazen and walking meditation. Other groups—many of the Community of Mindful Living and Shambhala practice groups, for example—are making do without formally trained leaders. These groups proliferate throughout the South, often drawing on teaching materials from the founders of their umbrella organizations, but lacking local ordained teachers.

Buddhism is also spreading rapidly through the many prisons of the South. Few people are more immediately aware of the truth of suffering than the incarcerated, and with the growth of the prison industry as a source of jobs and revenue, there are a lot more people locked away ro contemplate that suffering. Buddhist groups in many parts of the South, including Tibetan and Chinese Vajrayana, Zen, Pure Land, and Vipassana, have all reached our to spread the dharma behind bars.

Not surprisingly, the spread of various Buddhist lineages in the South hasn’t been completely uniform, and regional differences can sometimes be discerned. The Washington, D.C. area has a large Insight Meditation following, while Tibetan groups dominate Tennessee. Coastal North Carolina is riddled with Soka Gakkai groups, many of which originated with military wives at the state’s numerous armed forces bases. Zen is the most popular form of Buddhism in Louisiana but is virtually absent from South Carolina, and Texas has the largest concentration of Pure Land and Theravada temples.

Despite a relative paucity of trained Buddhist teachers in the South, there are some prominent and important centers for dharma study. Two of the nation’s best retreat centers are Sri Lankan monk Bhante Gunaratana’s Bhavana Society in West Virginia and the happily eclectic Southern Dharma Retreat Center in the far western part of North Carolina. Meanwhile, on North Carolina’s hurricane-stricken eastern shores, Venerable Phraktu Buddamonpricha from Thailand has embarked on plans to build a sort of Theravada pure land, complete with several large temples and meeting halls, houses for visitors, lodging for many monastics, and an avenue along which monks can beg for food. All this in a town so small that the closest thing it had to a non-traditional religion was the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

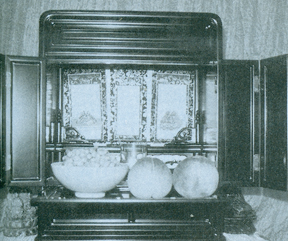

It’s much too soon to tell what will come from this meeting of East and South, but just as Buddhism will slowly make its mark in Dixie, so too will the surrounding culture begin to shape how dharma is understood and practiced. Sometimes the mutual exchange is a matter of small, virtually unnoticed details: traveling through the South, one can occasionally find black-eyed peas instead of sticky rice on home altars. At other times the local forms of expression are adopted with glee: the adage that everything is bigger in Texas has been taken to heart by a Theravada Buddhist monastery outside Forth Worth, whose followers brag with great pride that they have the largest Buddha statue in the United States of America. It’s a bit of a tall tale—the statue at Chuang Yen Monastery in Carmel, New York, is more than three times as tall—but the twenty-foot-tall gold Buddha, named Phra Ratana Sassada Satit America Saharat (“The Great Teacher in the United States”) is surely the largest Buddha in the former Confederate States of America.

In New Orleans, the Voodoo Spiritual Temple has incorporated Buddha images into its altars, while the Charlotte Community of Mindfulness, founded by dharma-interested congregation members, meets in the basement of Myers Park Baptist Church.

The Imperials are still recording Christian gospel music in Nashville, but times have changed and 01′ Buddha is here to stay. Driving my pickup truck past the endless cotton and tobacco fields of central North Carolina last year, I could often hear Nashville singer Jessica Andrew’s hit “Karma” on the radio, heralding a new influence in the lonelyhearts world of country music:

What comes around goes around I’m telling you baby.

It’s called karma.

What goes up comes down, Hits the ground.

You’re gonna find out All about

All about K-k-k-k-k-karma! ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.