There can be no compassion without wisdom. Indeed Buddhism teaches that wisdom and compassion are the two wings of the bird of enlightenment. By nurturing a compassionate heart which supports and is supported by an awareness that all “things” are empty of inherent existence, we can transcend our narrow sense of self and experience ourselves not as limited static entities but as part of a web of relationships. Few have combined compassion and wisdom with the brilliance of the great ninth-century Buddhist sage Shantideva, who taught that all the joy that exists in the world comes from wishing for the happiness of other sentient beings, and all misery from narrow egotism. To the extent that we care only for ourselves, he assured us, our lives will be filled with suffering. Could this, the heart of Buddhist teaching, ever be more relevant than it is today?

Today, fifty of the world’s largest economies are corporate, not national economies; almost all primary commodities, such as coffee and cotton, are controlled by six giant companies. The global economy they control is managed by giant transnational institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF and the World Trade Organization. These organizations are unaccountable to any democratic constituency.

Quite reasonable ideas have contributed to the rise of this system: The notion that trade is in everybody’s interest, for example, lies at the heart of the global economy. As a consequence, a broad spectrum of institutional pressures—from investments in infrastructure and research to regulations and direct subsidies—all promote trade for the sake of trade. As national governments have invested so much in trade, they have in fact supported the development of a transnational corporate system.

Today’s global economy, then, is made up of giant transnational corporations which by their very nature have but to generate maximum profits in as short a time as possible. Because of pressure from investors and shareholders, these corporations are forced to subordinate other priorities. There is little room for social, ecological, or spiritual values.

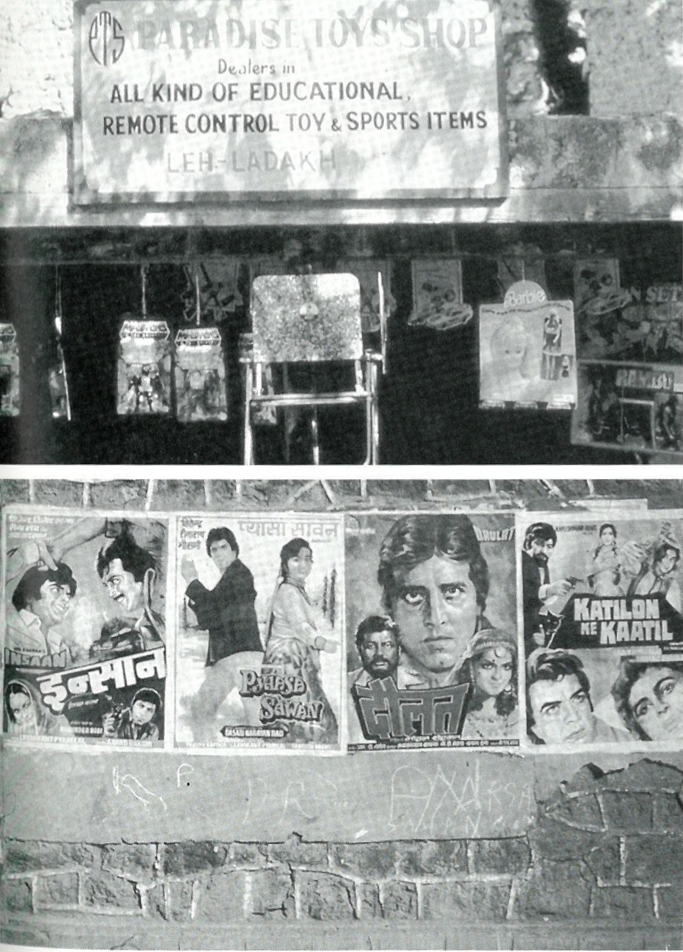

Today, cultures based on very different values that have existed for millennia are being amalgamated into a consumer monoculture. Even Buddhist societies that have sought to embody the notion that kindness and compassion should be at the heart of all human speech and actions are being undermined by the rampant materialism of the global economy. An unceasing tide of Western media, advertising, and cinematic propaganda is descending on these ancient cultures. Cleverly targeting the youngest members of society, these images promote the “new,” “modern,” “cool” way of life.

The effect of the Western monoculture in the Third World is to gut local cultures and to replace them with versions of happiness that serve commercial interests at the expense of social and ecological needs. We are persuaded to value our expensive house, car, annual holiday, and minidisc system above all else, but are blind to the fact that we are free to enjoy them in a world in which we are isolated from all deeper values, all deeper connections with ourselves, with each other, with the community and natural world around us. The irony is that we have perfect TV pictures, video images, and music, but the culture producing them is often so anemic and shallow that much of what we watch and hear is not worth attending to.

The problem for many Third World peoples, of course, is that, although they have been sold the dream, that is often all they are sold. Many have left rural communities for an urban, consumer dream, only to find themselves isolated and alone in dilapidated shanty towns, lost between two cultures.

Modern symbols also contribute to an increase in aggression. From Western-style films, young boys easily get the impression that if they want to be modern, they should smoke one cigarette after another, get a fast car, and race through the countryside shooting people left and right. Over the course of twenty-three years, I have witnessed changes wrought by Western “development” on the trans-Himalayan society of Ladakh. I have seen a gentle culture change, a culture in which men, even young men, were happy to cuddle a baby or be loving and soft with their grandmothers. Now the macho image reigns and

Rambo would not be caught dead with a baby, or with his grandmother, in his arms. Social changes of this kind are ultimately the product of changes in the economy. The global economy favors big businesses over small, and large global producers and retailers demand centralized, large-scale production; they also need concentrated centers of distribution. These large corporations are able to draw whole populations into urban centers. The result is that families and communities are torn apart as wage earners leave to make a living in the city. Local economies wither and dry, and people are forced off the land.

The global consumer culture is also contributing to a growing sense of personal insecurity. In virtually every culture before industrialization, there was lots of dancing, singing, and theater, with people of all ages joining in. Now that the radio has come to traditional communities, you do not need to sing your own songs or tell your own stories. Community ties are broken when people sit passively listening rather than making music or dancing together.

As they lose the sense of security and identity that springs from deep, long-lasting connections to others, people living in remote village communities are starting to develop doubts about who they are. At the same time, tourism and the media are presenting a new image of who they should be. They are meant to lead an essentially Western lifestyle: eating dinner at a dining table, driving a car, using a washing machine.

“Progress” speeds life up and mobility increases—making even familiar relationships more superficial and brief. In Ladakh and other parts of the Himalayas, I have seen previously strong, outgoing women replaced by a new generation—unsure of themselves and extremely concerned with their appearance.

Despite their new macho image, men do not exactly feel more powerful. When they are young, their obsession with looking cool prevents them from showing affection and emotion, while in later life as fathers, their work keeps them away from home and deprives them of contact with their children.

It is a feature of the global economy that a culture of scarcity replaces the abundance of natural resources and human kindness typical of traditional cultures: In their search for scarce jobs, scarce money, and scarce love, people become far more insecure and far less willing to do favors for other people—who become competitors rather than neighbors.

The challenge for Western Buddhists is to apply the Buddhist principles taught many centuries ago—in an age of relatively localized social and economic interactions—to the complex

and increasingly globalized world in which we now live. In order to do so it is vital that we avoid the mental traps of conceptual thought and abstraction. It is easy, for example, to confound the ideals of the “global village” and the borderless world of free trade with the Buddhist principle of interdependence—the unity of all life, the inextricable web in which nothing can claim completely separate or static existence. Buzzwords like “harmonization,” “integration,” “union,” etc., sound as though globalization is leaving us more interdependent with one another and with the natural world. In fact it is furthering our dependence on large-scale economic structures and technologies, and on a shrinking number of ever-larger corporate monopolies. It would be a tragic mistake to confuse this process with the cosmic interdependence described by the Buddha.

The three poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion are to some extent present in every human being, but cultural systems either encourage or discourage these traits. Noam Chomsky argues that the modern consumerist status quo requires a highly self-centered mindset:

It is necessary to destroy hope, idealism, solidarity, and concern for the poor and oppressed, to replace these dangerous feelings by self-centered egoism, a pervasive cynicism that holds that all change is for the worse, so that one should simply accept the state capitalist order with its inherent inequities and oppression as the best that can be achieved.

Today’s global consumer culture nurtures the three poisons on both an individual and societal level. At the moment, $450 billion is spent annually on advertising worldwide, with the aim of convincing three-year-old children that they need things they never knew existed. We need to recognize the extra difficulty of uncovering our Buddha-natures in a global culture of consumerism and social atomization.

Buddhism can help us in this difficult situation by encouraging us to be compassionate and nonviolent with ourselves as well as others. Many of us avoid an honest examination of our lives for fear of exposing our contribution to global problems. However, once we realize that it is the complex global economy which is creating a disconnected society, psychological deprivation, and environmental breakdown, Buddhism can help us to focus on the system and its structural violence, instead of condemning ourselves or other individuals within that system.

Buddhism, in its holistic approach, can help us to see how various symptoms are interrelated; how the crises facing us are systemic and rooted in economic imperatives. Understanding the myriad connections among the problems can prevent us from wasting our efforts on the symptoms of the crises, rather than focusing on their fundamental causes. Under the surface, even such seemingly unconnected problems as ethnic violence, pollution of the air and water, broken families, and cultural disintegration are closely interlinked.

Psychologically, such a shift in our perception of the nature of the problems is deeply empowering: Being faced with a never-ending litany of seemingly unrelated problems can be overwhelming, but finding the points at which they converge can make our strategy to tackle them more focused and effective. It is then just a question of pulling the right threads to affect the entire fabric, rather than having to deal with each problem individually.

At a structural level, the fundamental problem is scale. The ever-expanding scope and scale of the global economy obscures the consequences of our actions: In effect, our arms have been so lengthened that we no longer see what our hands are doing. Our situation thus exacerbates and furthers our ignorance, preventing us from acting out of compassion and wisdom.

Smaller-scale communities inevitably nurture more intimate relations among people, which in turn promote values and actions rooted in compassion and wisdom. In his book The Island of Bali, Miguel Covarrubias described how small-scale village life led to a situation in which cooperation was the norm among the Balinese, with neighbors assisting each other in every task they were unable to perform alone, helping each other willingly and as a matter of duty, expecting no reward. The result, Covarrubias writes, was a village system which operated as a “closely unified organism in which the communal policy is harmony and cooperation—a system that works to everybody’s advantage.”

On the other hand, the greedy, selfish, and violent aspects of human nature appear to be massively exaggerated in people living in larger-scale societies where intimate contact with the people around them has been reduced to vestigial levels. My own experience of life in Ladakh as well as many other cultures suggests that when people live in smaller-scale social and economic units, their natural happiness, friendliness, and capacity for kindness are enhanced to levels almost unimaginable to the average Western city-dweller. An important aspect of moving toward smaller-scale human institutions is reaffirming a sense of place. Human scale minimizes the need for rigid legislation and allows for more flexible decision making; it gives rise to action in harmony with the laws of nature, based on the needs of the particular context. When individuals are at the mercy of the faraway, inflexible bureaucracies and fluctuating markets, they feel passive and disempowered; more decentralized structures provide individuals with the power to respond to each unique situation.

Since the global economy is fueled by transnational institutions that can now overpower any single government, the policy changes most urgently needed are at the international level. In theory, what is required is quite simple: The governments that ratified “free trade” treaties like the Uruguay Round of GATT need to sit down around the same table again. This time instead of operating in secret—with transnational corporations at their side—they should be made to represent the interests of the majority. This can only happen if there is far more awareness at the grass roots, awareness that leads to real pressure on policy makers.

Even now, without the help from government and industry that a new direction in policy would provide, people are starting to change the economy from the bottom up. This process of localization has begun spontaneously, in countless communities all around the world. Because economic localization means an adaptation to cultural and biological diversity, no single blueprint would be appropriate everywhere. The range of possibilities for local grassroots efforts is therefore as diverse as the locales in which they take place. In many towns, for example, community banks and loan funds have been set up, thereby increasing the capital available to local residents and businesses and allowing people to invest in their neighbors and their community, rather than in a faceless global economy. In other communities, “buy local” campaigns are helping locally owned businesses survive even when pitted against heavily subsidized corporate competitors. These campaigns not only help keep money from leaking out of the local economy, but also help educate people about the hidden costs—to their own jobs, to the community and the environment—in purchasing cheaper but distantly produced products.

In some communities, Local Exchange and Trading Systems (LETS) have been established as an organized, large-scale bartering system. Thus even people with little or no “real” money can participate in and benefit from the local economy. LETS have been particularly beneficial in areas with high unemployment. The city government of Birmingham, England—where unemployment hovers at twenty percent—has been a co-sponsor of a highly successful LETS program. These initiatives have psychological benefits that are just as important as the economic benefits: A large number of people who were once merely “unemployed”—and therefore “useless”—are becoming valued for their skills and knowledge.

These and countless other initiatives around the world are a reflection of a growing awareness that it is far more sensible to depend on our neighbors and the living world around us than to depend on a global economic system built of technology and corporate institutions. For Buddhists faced with this same reality, the compassionate choice is to become engaged. Buddhism provides us with both the imperative and the tools to challenge the economic structures that are creating and perpetuating suffering. We cannot claim to be Buddhist and simultaneously support structures that are so clearly contrary to Buddha’s teachings, antithetical to life itself.

The economic and structural changes needed, of course, require shifts at the personal level as well. In part, these involve rediscovering the deep psychological benefits—the joy of being embedded in community. Another fundamental shift involves reintroducing a sense of connection with the place where we live. The globalization of culture and information has led to a way of life in which the nearby is treated with contempt. We get news from China but not next door, and at the touch of the remote we have access to all the wildlife of Africa. As a consequence, our immediate surroundings seem dull and uninteresting by comparison. A sense of place means helping ourselves and our children to see the living environment around us: reconnecting with the sources of our food—perhaps even growing some of our own—learning to recognize the cycles of the seasons, the characteristics of flora and fauna. Community could be rekindled through localization. Excessive mobility erodes community, but as we put down roots and feel more attachment to a place, our human relationships deepen and become more secure.

We are living in a society in which the flames of individual greed and ignorance have been institutionalized in the furnaces of the global marketplace. If we are to combat this systemic destructiveness, we need to appreciate that personal and political issues are inseparable. Our individual greed and ignorance support greedy and destructive forces within our economic and political systems. On the other hand, in a kind of vicious circle, these political and economic systems are also powerfully reinforcing these negative tendencies in the individual. We need to constantly remind ourselves of the goals and logic of a system that so powerfully and insidiously affects our behavior.

The economic and political forces driving the modern economy are powerful indeed. Ultimately, however, their power depends on our lack of awareness of the system of which we are a part. Movements rooted in wisdom and compassion could turn the tide.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.