According to the Buddhist monastic code, monks and nuns are not allowed to accept money or even to engage in barter or trade with laypeople. They live entirely in an economy of gifts. Lay supporters provide gifts of material requisites for the monastics, while the monastics provide their supporters with the gift of the teaching. Ideally—and to a great extent in actual practice—this is an exchange that comes from the heart, something totally voluntary. There are many stories in the texts emphasizing the point that the returns in this economy depend not on the material value of the object given, but on the purity of heart of the donor and recipient. You give what is appropriate to the occasion and to your means, when and wherever your heart feels inspired. For the monastics, this means that you teach, out of compassion, what should be taught, regardless of whether it will sell. For the laity, this means that you give what you have to spare and feel inclined to share. There is no price for the teachings, nor even a “suggested donation.” You give because giving is good for the heart and because the survival of the dharma as a living principle depends on daily acts of generosity.

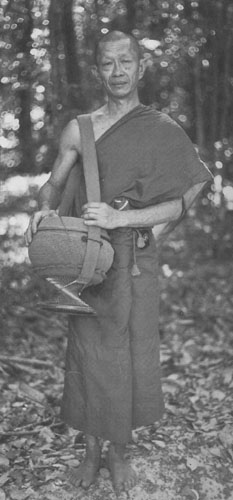

The primary symbol of this economy is the alms bowl. If you are a monastic, it represents your dependence on others, your need to accept generosity no matter what form it takes. You may not get what you want in the bowl, but you realize that you always get enough. Once a student of mine went to practice in the mountains in northern Thailand. His hillside shack was an ideal place to meditate, but he had to depend on a nearby hilltribe village for alms, and the diet was mostly plain rice, occasionally accompanied by some boiled vegetables. After two months on this diet, he was in conflict over whether or not to stay. One rainy morning, as he was on his alms round, a woman called out from a shack asking him to wait while she got some rice from the pot. As he waited, he couldn’t help grumbling inwardly about the fact that there would be nothing to go with the rice. It so happened that the woman’s infant son was sitting near the kitchen fire, crying from hunger. So as she scooped some rice out of the pot, she stuck a small lump in his mouth. Immediately, the boy stopped crying and began to grin. “Here you are, complaining about what these people are giving you for free,” my student told himself. “You’re no match for this little kid.” That lesson gave him the strength to stay in the mountains for another three years.

For a monastic, the bowl also represents the opportunity one gives others to practice the dharma. In Thailand, this is reflected in one of the idioms used to describe going for alms: proad sat, doing a favor for living beings. There were times on my alms round in rural Thailand when, as I walked past a tiny grass shack, someone would come running out to put rice in my bowl. Years earlier, as layperson, I would have wished to give them some material help. Now I was offering them the dignity that comes with being a donor.

For the donors, the monk’s bowl becomes a symbol of the good they have done. On several occasions in Thailand people told me they had dreamed of a monk standing before them, opening the lid to his bowl. The details differed as to what the dreamer saw in the bowl, but in each case the interpretation of the dream was the same: the dreamer’s merit was about to bear fruit.

The alms round itself is a gift that goes both ways. Daily contact with lay donors reminds the monastics that their practice is not just an individual matter. They are indebted to others for the opportunity to practice, and should do their best to practice diligently as a way of repaying that debt. Furthermore, walking through a village early in the morning, passing by the houses of the rich and poor, the happy and unhappy, gives plenty of opportunities to reflect on the human condition and the need to find a way out of the grinding cycle.

For the donors, the alms round is a reminder that the monetary economy is not the only way to happiness. It helps keep a society sane when there are monastics infiltrating the towns every morning, embodying an ethos very different from the dominant monetary economy. The gently subversive quality of this custom helps people to keep their values straight.

Above all, the economy of gifts allows for specialization, a division of labor from which both sides benefit. Those who are willing can give up many of the privileges of home life in return for the opportunity to devote themselves fully to dharma practice. Those who stay at home can benefit from having full-time dharma practitioners around on a daily basis. The Buddha began the monastic order on the first day of his teaching career because he saw the benefits that come with specialization. Without it, the practice tends to become diluted, negotiated into the demands of the monetary economy. The dharma becomes limited to what will sell and what will fit into a schedule dictated by the requirements of family and job. In this sort of situation, everyone ends up poorer in things of the heart.

The fact that tangible goods run only one way in the economy of gifts means that the exchange is open to all sorts of abuses. This is why there are so many rules in the monastic code to keep the monastics from taking unfair advantage of the generosity of lay donors. There are rules against asking for donations in inappropriate circumstances, against making claims as to one’s spiritual attainments, even against covering up any exceptional morsels in one’s bowl with rice in hopes that donors will then feel inclined to provide something more substantial. Most of the rules, in fact, were instituted at the request of lay supporters or in response to their complaints. They had made their investment in the merit economy and were interested in protecting their investment.

On their first contact with the sangha, most Westerners tend to see little reason for the disciplinary rules; they regard them as quaint holdovers from ancient Indian prejudices. When, however, they come to see these rules in the context of the economy of gifts, they too become advocates of the rules. The arrangement may limit the freedom of the monastics in certain ways, but it means that the lay supporters take an active interest in how the monastic lives—a useful safeguard to make sure that teachers walk their talk. This ensures that the practice remains a communal concern. As the Buddha said,

Monks, householders are very helpful to you, as they provide you with the requisites of robes, almsfood, lodgings, and medicine. And you, monks, are very helpful to householders, as you teach them the dharma admirable in the beginning, admirable in the middle, and admirable in the end, as you expound the holy life both in its particulars and in its essence, entirely complete, surpassingly pure. In this way the holy life is lived in mutual dependence, for the purpose of crossing over the flood, for making a right end to suffering and stress.

By its very nature, the economy of gifts is something of a hothouse creation that requires careful nurture and a sensitive discernment of its benefits. I find it amazing that such an economy has lasted for more than 2,600 years. It will never be more than an alternative to the dominant monetary economy, largely because its rewards are so intangible and require so much patience, trust, and discipline in order to appreciate them. But then, there is no way that the dharma can survive as a living principle unless it can be offered and received as a gift, in an atmosphere where mutual compassion and concern are the medium of exchange, and purity of heart is the bottom line.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.